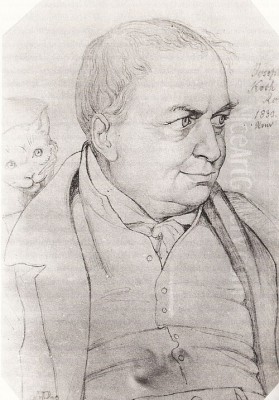

Joseph Anton Koch stands as a pivotal figure in the transition of European art at the turn of the 19th century. An Austrian-born painter, he masterfully navigated the currents of late Neoclassicism and burgeoning Romanticism, leaving an indelible mark primarily through his innovative approach to landscape painting. His life, marked by a rebellious spirit and an unwavering dedication to his artistic vision, took him from the pastoral idylls of the Tyrolean Alps to the vibrant artistic crucible of Rome, where he became a central personality among the German-speaking artists. Koch's legacy is not only in his breathtaking canvases but also in his influence on a generation of painters who sought to imbue nature with profound emotional and intellectual depth.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in 1768 in Elbigenalp, a small village in the Obergurgl valley of Tyrol, Austria, Joseph Anton Koch's early life was steeped in the rugged beauty of the Alpine landscape. His childhood was modest; he initially worked as a shepherd boy, an experience that undoubtedly fostered his intimate connection with nature. His artistic talents, however, did not go unnoticed. Through the patronage of a local bishop, believed to be Bishop Umgelder of Augsburg, Koch was afforded the opportunity for formal artistic training. This led him to the Karlsschule in Stuttgart in 1785, a prestigious but notoriously strict military academy that also offered art education.

At the Karlsschule, Koch was exposed to the prevailing artistic doctrines of the time, which were heavily influenced by Neoclassicism. However, the rigid discipline and pedagogical methods of the institution chafed against his independent spirit. The revolutionary ideas sweeping across Europe, particularly those emanating from the French Revolution, found a receptive mind in Koch. He began to express his discontent and his burgeoning political consciousness through satirical drawings, a risky endeavor within such a controlled environment. His rebellious streak culminated in his flight from the Karlsschule in 1791, an act of defiance that set him on a path of independent artistic exploration.

Formative Travels and the Call of Rome

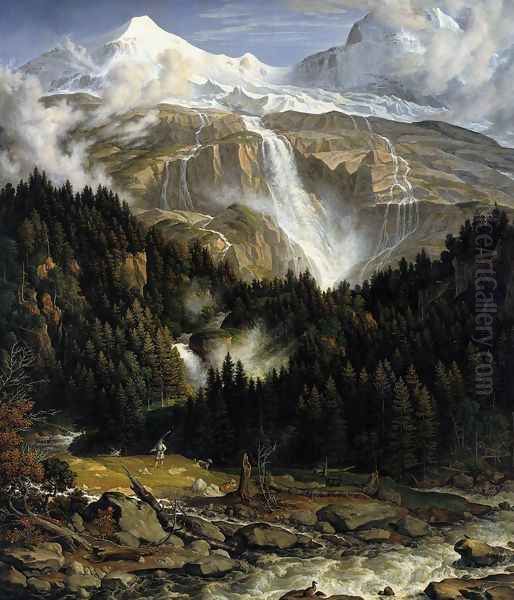

Freed from the constraints of formal academia, Koch embarked on a period of travel that proved crucial for his artistic development. He journeyed through France and Switzerland, immersing himself in diverse landscapes and absorbing new influences. The majestic scenery of the Swiss Alps, with its towering peaks, dramatic waterfalls, and expansive vistas, particularly captivated him. Between 1792 and 1794, he spent considerable time in Switzerland, creating numerous sketches and studies of Alpine nature. His depictions of waterfalls from this period are considered among his early triumphs, showcasing his ability to capture both the raw power and sublime beauty of the natural world.

These travels were not merely sightseeing expeditions; they were a vital process of gathering visual material and honing his observational skills. The sketches and impressions accumulated during these years would serve as a rich repository of inspiration for his later, more composed studio paintings. By 1795, Koch's artistic pilgrimage led him to Rome, the ultimate destination for aspiring artists from across Europe. The Eternal City, with its unparalleled artistic heritage, classical ruins, and vibrant international community of artists, was to become his adopted home and the primary stage for his mature career.

Rome: A New Artistic Milieu

Upon settling in Rome, Joseph Anton Koch quickly integrated into the city's dynamic art scene. He became a prominent member of the "Deutschrömer" (German-Romans), a circle of German-speaking artists who sought to revitalize art by drawing inspiration from both classical antiquity and the Italian masters. Within this community, Koch formed a significant friendship and artistic association with Asmus Jacob Carstens, a Danish-German painter whose intellectual rigor and commitment to Neoclassical ideals profoundly influenced him. Carstens, known for his large-scale figure compositions based on classical literature and mythology, encouraged Koch to think beyond mere topographical representation and to imbue his landscapes with historical and literary significance.

Koch's studio became a meeting point for many artists, and he was respected for his strong opinions and his dedication to his craft. He engaged with the legacy of 17th-century classical landscape painters like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, whose idealized and structured depictions of nature provided a crucial framework for his own developing style. However, Koch did not simply imitate these masters; he sought to synthesize their classical principles with his own direct experience of nature, particularly the wilder, more rugged terrains he had encountered in the Alps.

The Genesis of the Heroic Landscape

It was in Rome that Joseph Anton Koch pioneered and perfected what became known as the "heroic landscape" (heroische Landschaft). This genre represented a significant evolution in landscape painting, moving beyond the picturesque or purely topographical to create scenes of epic grandeur and profound meaning. Koch's heroic landscapes are characterized by their carefully constructed compositions, often featuring vast, panoramic views, dramatic mountain ranges, serene bodies of water, and meticulously rendered foliage. These natural elements are not merely decorative but are imbued with a sense of the sublime, evoking awe and wonder in the viewer.

A quintessential example of this style is his masterpiece, _Heroic Landscape with Rainbow_ (1805, with a later version in 1815). This iconic work, now housed in the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (another version in Munich), depicts an expansive, idealized Italianate landscape bathed in a clear, luminous light. A majestic rainbow arches across the sky, symbolizing hope and divine presence, while classical figures in the foreground add a narrative or allegorical dimension. The painting masterfully balances a detailed observation of natural phenomena with an overarching sense of order and harmony, reflecting Koch's belief in a divinely ordered universe. The work exemplifies his ability to elevate landscape painting to the level of history painting in terms of its intellectual and emotional impact.

Other works in this vein include landscapes populated with figures from the Bible or classical mythology, such as _Noah’s Thanksgiving Offering_ (1803). In this painting, the dramatic natural setting underscores the solemnity and significance of the biblical event. Koch’s landscapes often feature a strong sense of geological structure, reflecting his deep understanding of the earth's forms, combined with an almost spiritual appreciation for the atmospheric effects of light and weather.

Literary and Mythological Inspirations

Beyond his purely naturalistic or idealized landscapes, Koch was deeply engaged with literature, particularly the epic poetry of Dante Alighieri and the then-popular Ossianic poems. His illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy are among his most significant contributions to graphic art and reveal another facet of his Romantic sensibility. He produced a series of powerful and imaginative drawings and etchings depicting scenes from the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

One of his most notable projects in this area was his work on the frescoes in the Casino Massimo Lancellotti in Rome, undertaken in the 1820s. While artists like Peter von Cornelius, Friedrich Overbeck, and Philipp Veit, leading figures of the Nazarene movement, decorated other rooms with scenes from Dante, Tasso, and Ariosto, Koch was commissioned to paint scenes from Dante's Inferno in one of the rooms. His frescoes, such as the depiction of _Dante and Virgil in the Second Circle of Hell_, are characterized by their dramatic intensity and their faithful yet imaginative interpretation of Dante's text. _The Punishment of the Thieves in the Valley of Snakes and Dragons_ is another powerful example of his Dantean imagery, showcasing his ability to convey terror and divine retribution.

His interest in the Ossianic cycle, the epic poems purportedly translated by James Macpherson, also resulted in works like _The Death of Oscar from Paris_. These themes, with their emphasis on heroism, melancholy, and the wild, untamed aspects of nature, resonated strongly with the Romantic spirit of the age and found a compelling interpreter in Koch.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Ideals

Joseph Anton Koch's artistic style is a complex and fascinating synthesis of Neoclassical principles and Romantic sensibilities. From Neoclassicism, he inherited a respect for clarity of form, balanced composition, and the idealization of nature. His landscapes, however wild their subject matter, are always carefully structured, with a clear distinction between foreground, middle ground, and background, often leading the eye through a series of receding planes. This compositional rigor owes much to the example of Poussin.

From Claude Lorrain, Koch learned to master the depiction of light and atmosphere, creating landscapes suffused with a poetic, often elegiac mood. The soft, golden light that bathes many of his Italianate scenes is a testament to Lorrain's influence. However, Koch infused these classical traditions with a new intensity and a more personal emotional response to nature, characteristic of Romanticism. His Alpine scenes, for instance, convey a sense of the sublime – the awe-inspiring, sometimes terrifying, power of nature – that goes beyond the more tranquil Arcadian visions of his 17th-century predecessors.

Koch's meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of geological formations, trees, and plants, reflects a scientific curiosity combined with an artist's eye. He was not content with generalized forms but sought to capture the specific character of the natural world. Yet, this detailed realism was always subordinated to an overall idealizing vision. He aimed to represent not just nature as it is, but nature as it could be, a perfected and harmonious world that could elevate the human spirit.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Influence

Throughout his long career in Rome, Koch was a central figure in a vibrant artistic community. He interacted with a wide array of artists, both German-speaking and from other nations. His relationship with Asmus Jacob Carstens was formative, as mentioned. He also maintained connections with the Nazarenes, a group of German Romantic painters in Rome who sought to revive Christian art based on the models of the early Italian Renaissance. While Koch was primarily a landscapist and not a core member of the Nazarene brotherhood (which included figures like Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr, Peter von Cornelius, Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, and Philipp Veit), he shared some of their ideals, particularly their seriousness of purpose and their desire to create art with profound spiritual or moral content. He collaborated with some of them on projects like the Casino Massimo frescoes.

Koch also had significant interactions with other landscape painters. He was a contemporary of Johann Christian Reinhart, another leading German landscapist in Rome, with whom he shared an interest in idealized classical landscapes. While their approaches sometimes differed – Reinhart perhaps leaning more towards a Poussinesque historical landscape – they were key figures in establishing a German tradition of landscape painting in Italy. Koch also knew the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl, who visited Rome and was influenced by the city's artistic environment. Dahl, who later became a leading figure in Norwegian Romanticism, is known to have painted figures into at least one of Koch's landscapes, such as a version of The Lauterbrunnen Valley from Zweilütschinen. Another German painter, Christian Gottlieb Schick, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, also collaborated with Koch, for instance, on the painting Heroic Landscape with Ruth and Boaz, where Schick likely painted the figures.

The influence of earlier masters like Michelangelo and even Caravaggio can be discerned in the dramatic power and figural strength in some of Koch's works, particularly his Dante illustrations. He was also aware of the broader European artistic currents, including the work of French Neoclassicists who were active in Rome, such as pupils or followers of Jacques-Louis David and later Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Koch's impact extended to a younger generation of artists. His studio was a place of learning, and his powerful vision of landscape influenced many who came to Rome. Figures like Carl Philipp Fohr, a promising young German Romantic who tragically drowned in the Tiber, were inspired by Koch. Even the great German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, though working primarily in Germany and with a very different, more melancholic and overtly symbolic approach to landscape, operated within a similar intellectual framework that sought spiritual meaning in nature. Koch's Italianate Romanticism, however, offered a sunnier, more classical counterpoint to Friedrich's Northern Gothic sensibility. Later landscapists, such as Carl Blechen, who also spent time in Italy, would build upon the foundations laid by artists like Koch, though often moving towards a more realistic or proto-Impressionistic style. The Danish Golden Age painters, such as Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, who also studied in Rome, would have been aware of Koch's prominent position. Even the renowned Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, a dominant figure in Roman Neoclassicism, was part of this international artistic milieu.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Despite his artistic achievements and his central role in the Roman art world, Joseph Anton Koch often struggled financially. Patronage for landscape painting, even of the elevated "heroic" kind, was not always as forthcoming or lucrative as that for portraiture or grand history painting. He supplemented his income through the sale of drawings and etchings, which were popular among tourists and collectors. His etchings, in particular, helped to disseminate his compositions and his vision of landscape more widely.

He continued to paint with undiminished energy into his later years, revisiting favorite themes and locations, such as the waterfalls at Tivoli or the Alban Hills around Rome. His works from this period retain their power and clarity, though some critics have noted a tendency towards a harder, more linear style in his very late paintings.

Joseph Anton Koch died in Rome in 1839, at the age of 71. He was buried in the Teutonic Cemetery (Campo Santo Teutonico) within the Vatican City, a resting place for German-speaking Catholics in Rome. His death marked the end of an era, but his influence endured. He had successfully elevated landscape painting to a new level of intellectual and emotional significance, demonstrating that nature could be a vehicle for the most profound artistic expression.

Koch's true legacy lies in his successful fusion of classical order with Romantic feeling. He showed how the meticulous observation of nature could be combined with an idealizing vision to create landscapes that were both topographically convincing and poetically resonant. He provided a vital link between the classical landscape tradition of the 17th century and the Romantic landscapes of the 19th century, influencing generations of artists in Germany, Austria, and beyond. His "heroic landscapes" remain powerful testaments to the enduring beauty of the natural world and the human capacity to find meaning and inspiration within it. His numerous depictions of specific locales, such as _The Schmadribach Falls_, _Tirolean Landscapes_, _Uplands near Bern_, and views of Olevano Romano, became iconic representations of these sites, shaping the way they were perceived and painted by subsequent artists.

Conclusion

Joseph Anton Koch was more than just a skilled painter of mountains and trees; he was an artist-thinker who grappled with the great themes of nature, history, and the human spirit. His journey from a shepherd boy in Tyrol to a leading figure in the Roman art world is a testament to his talent and determination. By forging the "heroic landscape," he created a powerful new idiom for expressing the sublime and the ideal. He masterfully balanced the clarity and structure of Neoclassicism with the emotional intensity and imaginative freedom of Romanticism, creating a body of work that continues to inspire and captivate. As a bridge between two major artistic movements and as a mentor and inspiration to many, Joseph Anton Koch holds an undisputed place as one of the most important landscape painters of the early 19th century. His art remains a profound meditation on the majesty of nature and its deep connection to the human soul.