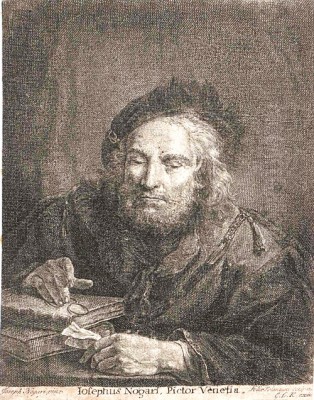

Giuseppe Nogari stands as a significant figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of 18th-century Venice. Born in Venice in 1699 and passing away in the same city in 1763, his life and career were deeply intertwined with the fortunes and tastes of the Venetian Republic during its final century of splendor. Nogari carved a distinct niche for himself within the Venetian School, becoming particularly renowned for his sensitive portraits, character studies, and allegorical figures, all rendered in the prevailing Rococo style. His work reflects both the specific artistic currents of Venice and broader European influences, securing him patronage both locally and internationally.

Early Life and Training in Venice

Giuseppe Nogari entered the world at the cusp of the 18th century, a time when Venice, though politically declining, was experiencing a remarkable artistic resurgence. The city was a crucible of talent, fostering painters, sculptors, musicians, and artisans who catered to a sophisticated local aristocracy and an increasing number of foreign visitors, particularly those on the Grand Tour. It was within this stimulating environment that Nogari began his artistic journey.

His initial training is generally believed to have been under Antonio Balestra, a respected painter who, although Veronese by birth, was active in Venice. Balestra's style, leaning towards a more classical and restrained late Baroque, likely provided Nogari with a solid foundation in drawing and composition. However, the most decisive influence on Nogari's development came from his association with Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. While the exact nature of their relationship (master-pupil or junior associate) is debated, Piazzetta's impact is undeniable. Piazzetta was a leading force in Venetian painting, known for his dramatic chiaroscuro, earthy realism, and expressive figure types.

Some sources also suggest a possible connection or early training with Giovanni Battista Pittoni, another prominent Venetian painter known for his lighter palette and fluid brushwork, characteristic of the Rococo. Regardless of the precise sequence of teachers, Nogari absorbed lessons from these masters, integrating them into his own evolving artistic personality. He was formally recognized early in his career, becoming a member of the Venetian painters' guild (Fraglia dei Pittori) around 1725.

Forging a Style: Influences and Development

Nogari's mature style represents a fascinating synthesis of various influences, skillfully adapted to the Rococo aesthetic. The shadow of Giovanni Battista Piazzetta looms large. From Piazzetta, Nogari adopted a penchant for strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), although Nogari typically softened these contrasts, aiming for more gentle transitions and a warmer, more atmospheric effect. Piazzetta's influence is also evident in Nogari's interest in depicting expressive heads and half-figures, often featuring elderly or rustic types, known as teste di carattere (character heads).

A crucial, though perhaps indirect, influence was the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt's powerful tronies – studies of heads conveying specific emotions or character types – had become highly sought after by collectors across Europe. Nogari clearly studied Rembrandt's work, likely through prints or paintings available in Venetian collections. He emulated Rembrandt's focus on psychological depth and the dramatic use of light, but translated these elements into the more elegant and refined language of the Rococo. Nogari's figures, even when depicting age or poverty, possess a certain grace and decorative quality distinct from Rembrandt's raw intensity.

The delicate art of Rosalba Carriera, Venice's celebrated pastellist, also left its mark on Nogari. Although Nogari primarily worked in oils, Carriera's success with intimate portraits, her subtle rendering of textures like skin and fabric, and her ability to capture fleeting expressions likely inspired him. He sought a similar psychological nuance and refined finish in his own portraits, particularly those of women, adapting the softness associated with pastel to the oil medium.

While drawing heavily on these key figures, Nogari did not simply imitate. He blended these influences – Piazzetta's tenebrism, Rembrandt's psychological depth, Carriera's delicacy, and perhaps Balestra's compositional structure – into a personal style characterized by meticulous technique, soft modeling, warm tonalities, and a gentle, often sentimental, mood.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Giuseppe Nogari's art is quintessentially Rococo in its elegance, charm, and focus on intimate subjects, yet it retains a connection to Venetian traditions of color and light. His brushwork is typically refined and controlled, allowing for a detailed rendering of surfaces, from the wrinkled skin of an old man to the lustrous sheen of silk. He excelled at capturing the play of light across forms, using soft, sfumato-like transitions rather than harsh lines to define contours. This creates a sense of atmosphere and volume, enveloping his figures in a gentle radiance.

His palette often favored warm earth tones, creams, soft reds, and golden browns, contributing to the intimate and approachable quality of his work. Even when depicting humble subjects, there is an inherent dignity and aesthetic appeal in his treatment. He paid close attention to textures, skillfully differentiating between rough wool, smooth skin, and delicate lace, adding a tactile quality to his paintings.

Nogari specialized in half-length portraits and teste di carattere. These formats allowed him to focus intensely on the face and upper body, conveying personality and emotion through subtle nuances of expression and gesture. His character heads, often depicting elderly men and women, philosophers, or allegorical figures, became particularly popular. These were not usually specific portraits but rather studies exploring types, moods, or virtues, appealing to the contemporary taste for sentimentalism and moral reflection. He often produced works in pairs or series, enhancing their decorative potential.

While oil on canvas was his primary medium, the influence of pastel, particularly in the softness of his modeling and the delicacy of his finish, is often noted. His technical skill was considerable, allowing him to work effectively on both small, intimate panels and larger canvases for more formal commissions.

Themes and Genres: Portraits, Allegories, and Religion

Portraiture formed the core of Nogari's output. He painted members of the Venetian nobility and bourgeoisie, as well as foreign dignitaries and visitors. His portraits are valued for their likeness, but also for their elegance and psychological insight. He often depicted sitters in allegorical guise, such as his Portrait of a Lady as Diana, blending portraiture with mythological themes popular in the Rococo period.

His teste di carattere represent a significant portion of his work and were highly sought after by collectors. These included venerable old men, often depicted as philosophers or scholars contemplating mortality or wisdom, and elderly women, sometimes shown engaged in simple domestic tasks or representing virtues like piety or resilience. A famous example is the Portrait of Archimedes, noted by contemporaries for depicting the ancient mathematician holding a pair of compasses – an instrument, in that specific form, anachronistic to Archimedes' time, perhaps reflecting Nogari's interest in symbolic representation over strict historical accuracy. Another well-known type is the Old Woman with a Brazier (versions exist, notably one associated with the Dresden collection), a poignant study of age and warmth.

Alongside portraits and character heads, Nogari also produced religious paintings, particularly earlier in his career. He executed altarpieces and devotional works for churches in Venice and the surrounding Veneto region. Examples include Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter and the Miracle of St. Joseph of Copertino. He also painted religious subjects for foreign patrons, notably for German collectors, indicating the international reach of his reputation even in this genre.

Allegorical subjects also featured in his oeuvre. Series like The Four Seasons, represented by figures embodying each season's attributes, catered to the Rococo taste for decorative cycles that could adorn the interiors of palaces and villas. These works allowed Nogari to combine his skill in figure painting with imaginative and symbolic content.

Patronage, Commissions, and Recognition

Nogari enjoyed considerable success and patronage throughout his career. His ability to capture both a likeness and an air of refined elegance made him popular with aristocratic patrons in Venice. His character heads found a ready market among local collectors and foreign visitors on the Grand Tour, who sought souvenirs of Venetian art.

Crucially, Nogari attracted significant international patronage. One of his most important patrons was Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, who acquired a substantial number of Nogari's works, particularly character heads, for his magnificent picture gallery in Dresden (the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister). This royal patronage significantly boosted Nogari's international standing. He also worked for the House of Savoy, receiving commissions from Charles Emmanuel III, King of Sardinia.

Another key connection was with Consul Joseph Smith, the British consul in Venice, who was a major collector and patron of Venetian artists, including Canaletto and Rosalba Carriera. Smith's collection, eventually sold to King George III, helped to introduce Nogari's work to British audiences. The German merchant Sigismund Streit, residing in Venice, was another important patron, commissioning works from Nogari, including religious paintings, which eventually went to collections in Germany.

Nogari's standing within the Venetian art establishment was confirmed by his involvement with the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia (Venice Academy of Fine Arts). He was not only a member but was recognized as one of its founding members when it was formally established in 1756, serving as a professor of painting. This position underscored his reputation and his role in shaping the next generation of artists.

Teaching and Influence: Nogari's Workshop and Students

As a respected master and professor at the Academy, Giuseppe Nogari played a role in educating younger artists. His studio likely attracted apprentices and assistants who helped with commissions and learned his techniques. His influence extended through his direct pupils and through the broader dissemination of his style.

Among his most notable students was Alessandro Longhi, son of the genre painter Pietro Longhi. Alessandro became a prominent portraitist in his own right, and while developing his own style, his work sometimes shows the influence of Nogari's approach to characterization and technique.

Nogari also taught Joseph Wagner (or Giuseppe Wagner), who became a highly successful engraver and print publisher in Venice. Wagner engraved many of Nogari's popular character heads, helping to spread Nogari's compositions and fame far beyond Venice. These prints were widely collected and further cemented Nogari's reputation as a master of expressive physiognomy.

Other artists associated with Nogari as students or followers include Charles-Joseph Flipart, a French painter and engraver active in Venice; Pietro Antonio Novelli, a versatile painter and engraver; and Antonio Zucchi, who later achieved success in England as a decorative painter. The sculptor Michelangelo Morlaiter is also sometimes mentioned in connection with Nogari's circle, reflecting the interconnectedness of the arts in Venice. Through these students and the popularity of his work, Nogari's style influenced portraiture and figure painting in Venice in the mid-18th century.

Nogari in the Venetian Art World

Giuseppe Nogari operated within one of the most dynamic art centers in Europe. His career unfolded alongside giants like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, whose vast decorative schemes and luminous frescoes dominated large-scale commissions. While Nogari did not compete directly in Tiepolo's field of monumental history painting, he carved out a successful niche in the more intimate genres of portraiture and character studies.

He was a contemporary of Pietro Longhi, who specialized in charming genre scenes depicting Venetian daily life, and the great view painters Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, who captured the city's unique topography and atmosphere. Within portraiture, he shared the stage with Rosalba Carriera, whose pastel portraits were internationally acclaimed. Nogari offered an alternative in oils, blending realism with Rococo elegance.

The snippets mention potential competition with figures like Giovanni Corvino, indicative of the competitive nature of the Venetian art market, where numerous talented artists vied for commissions and patronage. Nogari's success in securing prestigious local and international patrons speaks to his skill and the appeal of his particular style.

He also engaged in collaborations, as was common practice. The mention of him adding figures to fresco scenes by landscape specialists highlights the cooperative aspect of large decorative projects in villas and palaces. His relationship with engravers like Joseph Wagner was also symbiotic, benefiting both the painter's reputation and the engraver's business. Nogari was thus an active participant in the complex network of artists, patrons, dealers, and publishers that constituted the Venetian art world. His work was featured in exhibitions, such as one in Milan mentioned in the sources, and included in thematic shows like the "Sebastiano Ricci, rivals and heirs" exhibition at Palazzo Fulci, demonstrating his recognized place within the lineage of Venetian painting.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Giuseppe Nogari remained active as a painter and teacher until his death in Venice in 1763. He continued to produce portraits and character heads, refining his style and fulfilling commissions for his established network of patrons. His role as a founding professor at the Academy cemented his status as a respected elder statesman of Venetian art in his final years.

His legacy lies primarily in his contribution to portraiture and the genre of the testa di carattere. He successfully adapted influences from the Baroque, particularly Rembrandt and Piazzetta, to the lighter sensibilities of the Rococo, creating works that were both psychologically engaging and decoratively appealing. His character heads, in particular, enjoyed immense popularity and were widely imitated and disseminated through prints.

Nogari's work represents a specific facet of the Venetian Settecento – less grandiose than Tiepolo, less documentary than Canaletto or Pietro Longhi, but possessing a unique blend of realism, elegance, and gentle sentiment. He captured a sense of intimacy and refined sensibility that resonated with the tastes of his time and continues to appeal to viewers today. His paintings offer insight into the personalities and preoccupations of 18th-century Venice, from its aristocracy to its fascination with character, allegory, and the passage of time.

Collections and Exhibitions: Where to See Nogari's Art

Works by Giuseppe Nogari are held in numerous public and private collections across Europe and North America, reflecting his contemporary popularity and enduring appeal. Significant holdings can be found in institutions that benefited from his major patrons.

The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany, holds a substantial collection of his character heads, acquired by Augustus III. These works provide an excellent overview of this important aspect of his oeuvre.

In Italy, his works can be found in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, which houses paintings representative of the Venetian school, and potentially other Venetian museums or churches for which he originally worked. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence and other Italian museums also hold examples, often character heads.

The Nationalmuseum in Stockholm possesses works linked to Nogari, reflecting acquisitions by the Swedish royal collections. The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, another repository of vast European art collections, also includes paintings by Nogari.

Works occasionally appear in exhibitions dedicated to 18th-century Venetian art or the Rococo period. His inclusion in the Palazzo Fulci exhibition alongside Sebastiano Ricci and others underscores his historical importance within the Venetian school. Major museums in the United Kingdom and the United States may also have examples of his portraiture or character studies, often stemming from Grand Tour acquisitions or later collecting patterns. Tracking his work involves looking through collections rich in Italian Baroque and Rococo art.

Conclusion: Nogari's Place in Art History

Giuseppe Nogari remains a distinguished figure within the rich tapestry of 18th-century Venetian painting. While perhaps overshadowed internationally by contemporaries like Tiepolo or Canaletto, he was a master in his chosen field. His specialization in portraiture and character heads allowed him to develop a distinctive style that skillfully blended the dramatic intensity of the Baroque tradition with the elegance and refinement of the Rococo.

His technical proficiency, his sensitivity to light and texture, and his ability to convey subtle psychological states earned him widespread acclaim and prestigious patronage during his lifetime. Through his own work, his teaching at the Venice Academy, and the dissemination of his compositions via engravings, Nogari made a significant contribution to the art of his time. His paintings endure as captivating examples of Venetian Rococo portraiture, offering intimate glimpses into the faces and sensibilities of a bygone era. He remains an artist whose works reward close attention, revealing a delicate balance of realism, elegance, and human feeling.