Giuseppe Vasi stands as a pivotal figure in eighteenth-century Italian art, an artist whose meticulous engravings and architectural insights have provided invaluable records of Rome during a period of significant cultural and urban transformation. Born in Sicily and later establishing himself in the Eternal City, Vasi became one of the most prolific and influential producers of vedute, or view paintings and prints, capturing the grandeur of Rome's ancient ruins, its magnificent Baroque churches, and the bustling life of its piazzas and streets. His work not only catered to the burgeoning Grand Tour market but also served as a comprehensive visual encyclopedia of the city, influencing contemporaries and shaping the perception of Rome for generations to come.

Early Life and Sicilian Origins

Giuseppe Vasi was born on August 27, 1710, in Corleone, a town in Sicily. His early artistic inclinations likely found nurturing in the local artistic environment of Sicily, which, though geographically distant from the major art centers of mainland Italy, possessed a rich cultural heritage influenced by various civilizations. Information about his formative training in Sicily is somewhat scarce, but it is understood that he received initial instruction in painting and engraving. The artistic scene in Sicily at the time would have exposed him to late Baroque traditions, often with a distinct local character.

Around 1736, seeking greater opportunities and exposure to the classical and contemporary artistic currents, Vasi made the significant decision to move to Rome. This relocation was a common path for ambitious artists from the Italian peripheries and beyond, as Rome was then, as it had been for centuries, the undisputed center of the art world, a living museum of antiquity, and a vibrant hub of contemporary artistic production under Papal and aristocratic patronage. His arrival in Rome marked the true beginning of his professional career and his immersion into a highly competitive and stimulating artistic milieu.

Arrival in Rome and Artistic Development

Upon settling in Rome, Vasi quickly sought to establish himself. He found employment at the Calcografia Camerale (later the Calcografia Nazionale), the papal printmaking institution. This was a significant step, as the Calcografia was responsible for producing and disseminating high-quality engravings, often with official or semi-official sanction. Working here would have honed his technical skills in etching and engraving and provided him with valuable connections within the Roman art world.

Vasi's artistic development in Rome was shaped by several factors. The city itself, with its unparalleled concentration of ancient monuments, Renaissance palaces, and Baroque churches, provided an inexhaustible source of subject matter. He was also exposed to the work of established vedutisti (view painters) like Giovanni Paolo Panini, whose picturesque and often monumental depictions of Roman scenes were highly popular. While Panini worked primarily in painting, his compositions and approach to urban landscape undoubtedly influenced printmakers like Vasi.

Vasi specialized in the technique of etching, often finishing his plates with engraving to achieve finer details and richer tonal variations. His style was characterized by a commitment to topographical accuracy, a clear and precise delineation of architectural forms, and an ability to convey the scale and atmosphere of Roman spaces. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might take artistic liberties for dramatic effect, Vasi generally prioritized a faithful representation of his subjects, making his works valuable historical documents.

The Grand Tour and the Market for Vedute

The eighteenth century witnessed the flourishing of the Grand Tour, an educational rite of passage for young European noblemen and wealthy commoners. Rome was an essential stop on this itinerary, and visitors were eager for souvenirs and visual records of the city's wonders. This demand fueled a thriving market for vedute, both paintings and, more affordably, prints. Giuseppe Vasi was exceptionally well-positioned to cater to this market.

His prints offered detailed and accurate views of famous landmarks, ancient ruins, and contemporary Roman life. They were relatively inexpensive compared to paintings, easily transportable, and could be bound into albums, serving as a visual diary of one's travels. Vasi's systematic approach to documenting the city, often organizing his prints into thematic series, appealed to the encyclopedic interests of the Enlightenment era. His workshop became a significant production center, employing assistants to help with the laborious process of printmaking to meet the consistent demand.

The influence of artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) and Bernardo Bellotto, though primarily associated with Venice, also permeated the broader Italian veduta scene. Their mastery of perspective, light, and atmospheric effects set a high standard for view painting and printmaking across Italy, and Vasi would have been aware of their widespread acclaim and stylistic innovations.

Major Works: Documenting the Magnificence of Rome

Giuseppe Vasi's reputation rests largely on his monumental print series and his cartographic endeavors, which together offer an unparalleled visual survey of eighteenth-century Rome.

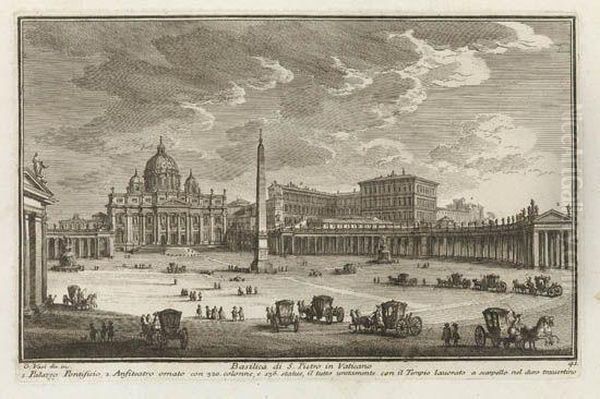

Delle Magnificenze di Roma antica e moderna

Vasi's magnum opus is undoubtedly Delle Magnificenze di Roma antica e moderna (The Magnificence of Ancient and Modern Rome). Published in ten books between 1747 and 1761, this ambitious project comprised a total of 240 large-format etchings. Each book focused on a specific aspect of the city:

Book I (1747): Gates and Walls of Rome

Book II (1752): Main Piazzas

Book III (1753): Basilicas and Ancient Churches

Book IV (1754): Palaces and Streets

Book V (1756): Bridges and buildings on the Tiber

Book VI (1756): Parish Churches

Book VII (1758): Monasteries and Convents

Book VIII (1759): Monasteries for Nuns

Book IX (1761): Colleges, Seminaries, and Hospitals

Book X (1761): Villas and Gardens

This systematic organization made the Magnificenze an invaluable resource for both tourists and scholars. The prints are characterized by their meticulous detail, accurate perspective, and lively staffage (human figures and animals that populate the scenes). Vasi often included scenes of daily life – carriages, street vendors, pedestrians – which animate the architectural views and provide a glimpse into the social fabric of the city. The architectural subjects themselves spanned the full history of Rome, from ancient ruins like the Colosseum and the Pantheon to the great Baroque churches of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, and contemporary structures by architects like Alessandro Galilei and Ferdinando Fuga.

Maps and Guidebooks

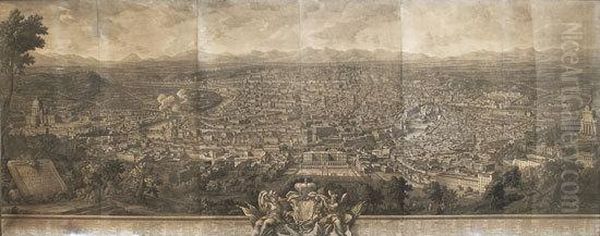

Beyond his extensive series of views, Vasi was also an accomplished cartographer. His most famous map is the Nuova Pianta di Roma (New Map of Rome), first published in 1748 and later revised, notably the monumental version of 1781 known as the Prospetto dell'Alma Città di Roma visto dal Monte Gianicolo. This large panoramic map, often printed on multiple sheets, offered a bird's-eye view of the entire city, remarkable for its detail and accuracy. It was a significant achievement in urban cartography, rivaling and complementing the slightly earlier and more planimetric map by Giambattista Nolli (1748).

Vasi also authored guidebooks, most notably the Itinerario Istruttivo Diviso in Otto Giornate per ritrovare con facilità tutte le antiche e moderne magnificenze di Roma (Instructive Itinerary Divided into Eight Days to easily find all the ancient and modern magnificences of Rome), published in 1763 and subsequently revised. This guidebook, often accompanied by his prints, provided practical routes for exploring the city, reflecting his deep knowledge of Roman topography and history. Interestingly, in his Itinerario, Vasi made a point of mentioning works by female artists, a noteworthy inclusion for guidebooks of that era.

The Relationship with Giovanni Battista Piranesi

One of the most discussed aspects of Vasi's career is his relationship with Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), who would become the most famous Roman vedutista of the eighteenth century. Piranesi, upon arriving in Rome from Venice around 1740, briefly worked in Vasi's studio to learn the etching technique.

Accounts suggest that Vasi recognized Piranesi's prodigious talent but perhaps also his temperament. A famous, possibly apocryphal, anecdote recounts Vasi telling Piranesi, "You are too much a painter, my friend, to be an engraver." This remark has been interpreted in various ways: as a recognition of Piranesi's imaginative and dramatic flair, which seemed more suited to the freedom of painting than the precision Vasi associated with engraving; or perhaps as a subtle critique of Piranesi's less disciplined approach to the exacting craft of printmaking as Vasi practiced it.

Whatever the exact nature of their early interactions, the two artists' paths diverged. Piranesi developed a highly personal and dramatic style, characterized by bold contrasts of light and shadow, exaggerated perspectives, and a romantic, often melancholic, vision of Rome's ancient grandeur. While Vasi's prints were prized for their clarity and topographical accuracy, Piranesi's vedute and his famous Carceri d'Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons) aimed for a more profound emotional and intellectual impact.

Though they became, in a sense, competitors in the market for Roman views, their approaches were distinct. Vasi's Rome is a well-ordered, observable city, meticulously documented. Piranesi's Rome is a sublime, awe-inspiring stage for reflections on history, decay, and human ambition. In later years, as Piranesi's fame grew, Vasi's more traditional style was somewhat overshadowed, though his work never ceased to be valued for its documentary importance.

Other Collaborations and Contemporaries

Giuseppe Vasi was an active participant in the Roman art scene and collaborated with various artists and patrons throughout his career. His work for the Calcografia Camerale inherently involved interaction with other printmakers and officials. He collaborated with the scholar Giovanni Gaetano Bottari on some projects, including a book celebrating the birth of a son to Charles III of Naples (later of Spain), which helped Vasi gain official recognition.

He also worked with architects and draughtsmen. For instance, some of his prints were based on drawings by other artists, or depicted architectural projects by leading architects of the day. He engraved plates for projects involving architects like Paolo Posi and Giuseppe Palazzi. His early work in Rome included providing etchings for a publication on Filippo Juvarra's designs for the Superga Basilica's royal mausoleum in Turin. He is also known to have collaborated with artists such as Antonio Bova, Cesare Ficchè, and Nicola Palma on projects like La Reggia in Trionfo. Riccardo Vanini is another artist with whom Vasi had professional associations.

Vasi's contemporaries in Rome included a host of talented painters, sculptors, and architects. Besides Panini and Piranesi in the realm of vedute, the leading painters in Rome included Pompeo Batoni, known for his elegant portraits of Grand Tourists, and Anton Raphael Mengs, a key figure in the rise of Neoclassicism. Sebastiano Conca and Pier Leone Ghezzi were established figures from an older generation whose influence was still felt. The architectural landscape was dominated by figures like Ferdinando Fuga and Luigi Vanvitelli (before Vanvitelli's move to Naples to design the Caserta Palace). The legacy of Baroque masters like Bernini, Borromini, and Carlo Fontana was everywhere, providing much of the subject matter for Vasi's prints.

Vasi's Rome: A Social and Architectural Document

Beyond their artistic merit, Giuseppe Vasi's prints are invaluable historical documents. They offer a comprehensive visual record of Rome at a specific moment in its history, capturing not only its famous monuments but also its urban fabric – streets, squares, bridges, and everyday buildings. His inclusion of staffage provides insights into eighteenth-century Roman life: the modes of transport, street activities, social interactions, and even details of costume.

His views often show buildings that have since been altered or demolished, or urban spaces that have been reconfigured. For architectural historians, Vasi's prints can be crucial for understanding the state of a building or site in the mid-eighteenth century. His attention to detail extended to inscriptions, sculptural decorations, and the surrounding environment.

Vasi's depiction of Rome also reflects the city's complex character – a place where ancient ruins coexisted with magnificent Renaissance and Baroque structures, and where sacred and secular life were intricately intertwined. His prints capture the grandeur of papal ceremonies, the bustle of market squares, and the quietude of monastic cloisters. He even depicted less savory aspects of urban life, such as public urination, adding a layer of unvarnished realism to his otherwise polished views. This comprehensive approach makes his body of work a rich resource for social historians as well as art and architectural historians.

Later Years and Legacy

Giuseppe Vasi remained productive throughout his life. He continued to revise and republish his major works, adapting to changing tastes and updating his views to reflect alterations in the urban landscape. He held the respect of many, and his workshop was a known entity for anyone seeking comprehensive views of Rome. He was also a teacher, passing on his skills to his son, Mariano Vasi, who also became an engraver and continued his father's business, and, of course, to the young Piranesi.

Despite the rising fame of Piranesi, whose dramatic and imaginative style increasingly captured the Romantic imagination, Vasi's work retained its value, particularly for its accuracy and comprehensiveness. His prints were seen as reliable visual records, essential for anyone studying the topography and architecture of Rome.

Giuseppe Vasi died in Rome on April 16, 1782. He left behind an immense corpus of work that continues to be studied and appreciated. His legacy is multifaceted:

As a Documentarian: He created one of the most complete visual records of any city in the eighteenth century. His prints are primary sources for understanding the appearance and life of Rome before the significant changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

As an Artist: His technical skill as an etcher and engraver was considerable. His compositions are well-ordered, his perspectives accurate, and his ability to render architectural detail is remarkable.

As an Influence: While Piranesi ultimately achieved greater international fame, Vasi played a crucial role in the development of the veduta tradition in Rome. He trained Piranesi in the basics of etching and set a standard for topographical accuracy that influenced other printmakers.

As a Facilitator of the Grand Tour: His prints and guidebooks helped shape the experience of Rome for countless Grand Tourists, disseminating images of the city throughout Europe and contributing to its enduring allure.

Museums and collections worldwide hold impressions of Vasi's prints, and they remain essential for scholars and enthusiasts of Roman history and art. His dedication to chronicling the "Magnificence of Ancient and Modern Rome" ensured that his vision of the Eternal City would endure.

Conclusion

Giuseppe Vasi was more than just a skilled engraver; he was a visual historian, a cartographer, and an entrepreneur who understood the cultural and commercial currents of his time. His systematic and detailed documentation of eighteenth-century Rome, from its grandest monuments to its everyday scenes, has provided an enduring legacy. While often compared to his more famous pupil, Piranesi, Vasi's contribution stands on its own merits. His commitment to accuracy, his comprehensive scope, and his ability to capture the unique character of Rome make his work an indispensable resource for understanding the Eternal City during a vibrant period of its history. Through his thousands of etched lines, Giuseppe Vasi brought the Rome of his era to life, preserving its splendors for posterity.