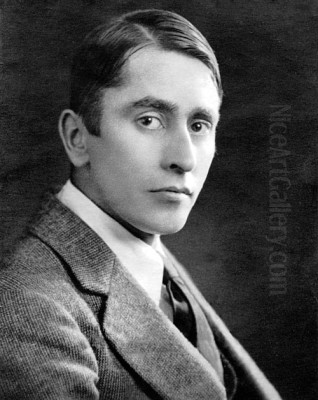

Harry Clarke stands as one of Ireland's most distinctive and influential artists of the early 20th century. Born Henry Patrick Clarke on March 17, 1889, in Dublin, he forged a remarkable, albeit tragically short, career as both a stained-glass artist and a book illustrator. His work, deeply embedded in the traditions of Art Nouveau and Symbolism, yet uniquely his own, continues to captivate audiences with its intricate detail, vibrant colour, and often unsettling, otherworldly beauty. Clarke was a pivotal figure in the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement, leaving an indelible mark on the visual culture of his nation and beyond before his untimely death on January 6, 1931.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Harry Clarke's immersion in the world of art began almost from birth. His father, Joshua Clarke, was a prosperous craftsman and businessman who ran a church decorating firm in Dublin. This firm, Joshua Clarke & Sons, later expanded to include a stained-glass division, providing young Harry with an early and intimate exposure to the medium that would become one of his primary forms of expression. The bustling workshop environment, filled with designs, materials, and the hum of creation, undoubtedly shaped his artistic inclinations.

His mother, Brigid McGonagall Clarke, also played a role in his early life, though her death in 1903, when Harry was just a teenager, was a significant blow. He received his initial formal education at Belvedere College in Dublin, a Jesuit institution. However, following his mother's passing, he left Belvedere and began to apprentice more formally in his father's studios. This practical training was crucial, grounding him in the technical aspects of craftsmanship, particularly in stained glass.

To further hone his artistic talents, Clarke enrolled at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (now the National College of Art and Design). Here, he studied under prominent figures of the Irish Arts and Crafts movement, including William Orpen and Alfred Ernest Child, the latter being a particularly important instructor in stained glass technique. Clarke proved to be a prodigious student. His exceptional talent was recognized in 1910 when he won a coveted gold medal in the National Competition for his stained-glass panel, "The Consecration of St. Mel, Bishop of Longford, by St. Patrick." This award signaled the arrival of a major new talent in Irish art.

During his time at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, he also met Margaret Crilly, a talented painter and fellow student. Their shared passion for art blossomed into a romance, and they married in 1914. Margaret became an important partner and supporter throughout his career, and they had three children: Michael, David, and Ann.

The Emergence of a Unique Visual Language

Harry Clarke's artistic style is instantly recognizable, characterized by its meticulous detail, elongated and often ethereal figures, rich, jewel-like colours, and a penchant for the fantastical, the grotesque, and the decadent. His work is a fascinating synthesis of various influences, masterfully blended into a highly personal visual language.

The sinuous lines, decorative patterning, and organic motifs of Art Nouveau are clearly evident in his compositions. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley, with his exquisite and often perverse black and white illustrations, were a profound influence, particularly on Clarke's graphic work. The intricate detail and the way figures are often enmeshed in complex decorative schemes owe much to Beardsley's example. One can also see echoes of the Vienna Secession artists, such as Gustav Klimt, in the opulent surfaces and symbolic richness of Clarke's designs.

French Symbolism, with its emphasis on suggestion, dreams, and the inner world, also deeply resonated with Clarke. The works of painters like Gustave Moreau, with their mythological and biblical scenes rendered in jewel-like colours and intricate detail, and Odilon Redon, with his explorations of the subconscious and the bizarre, find parallels in Clarke's own imaginative flights. The Symbolist fascination with the femme fatale, the mysterious, and the melancholic are recurring themes in his art. Edvard Munch's expressive intensity and psychological depth also seem to have left an impression.

Furthermore, Clarke's style drew from earlier artistic traditions. The elongated figures and vibrant colours of medieval stained glass and manuscript illumination were a constant source of inspiration. He was particularly adept at using the lead lines in stained glass not merely as structural necessities but as integral parts of the drawing, a technique that harks back to the best medieval craftsmanship. Gothic art's fascination with the macabre and the spiritual also informed his sensibility.

The cultural ferment of the Irish Revival, which sought to create a distinctly Irish cultural identity through literature, language, and art, provided a backdrop to Clarke's development. While his themes were often universal or drawn from European literature, the intensity and imaginative power of his work can be seen as part of this broader flourishing of Irish creativity.

Master of Light and Colour: The Stained Glass

Harry Clarke's contribution to stained-glass art is monumental. He produced over 130 stained-glass windows for religious and secular settings, primarily in Ireland but also in England, Australia, and the United States. He inherited his father's business, Joshua Clarke & Sons, after Joshua's death in 1921, and under Harry's artistic direction, the studio produced some of its most exceptional work.

Clarke was a technical virtuoso. He pushed the boundaries of the medium, employing techniques such as acid-etching to achieve subtle gradations of tone and texture, plating (layering pieces of glass) to create incredibly rich and deep colours, and masterful painting on glass. His use of colour is particularly renowned, especially his signature deep blues, which seem to glow with an inner light, and his vibrant reds, greens, and golds.

One of his earliest and most significant commissions was for the Honan Chapel at University College Cork, completed between 1915 and 1917. These windows, depicting Irish saints, are a tour-de-force of design and craftsmanship, showcasing his already mature style. The figures are elegant and attenuated, clothed in sumptuously patterned robes, and set against backgrounds filled with intricate detail. Windows such as St. Gobnait, with its depiction of the saint and her bees, and St. Patrick, are iconic examples of early 20th-century Irish stained glass. These works established Clarke as a leading figure in the field, rivaling and often surpassing the output of established studios like An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass), founded by Sarah Purser and home to artists like Michael Healy and Wilhelmina Geddes. Evie Hone, another significant Irish stained glass artist, also worked during this period, though her style evolved differently.

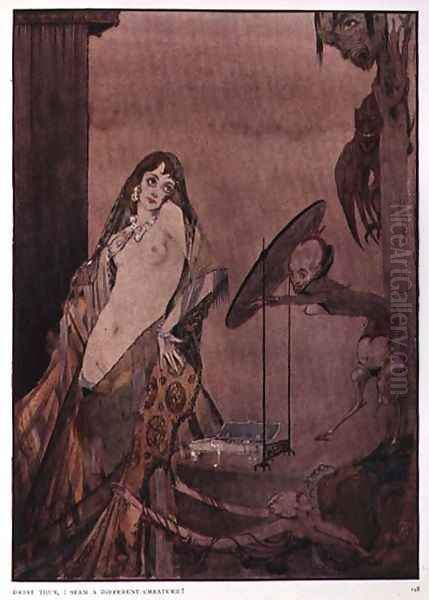

Perhaps Clarke's most famous, and certainly most controversial, stained-glass work is "The Eve of St. Agnes." This series of panels, illustrating John Keats's romantic poem, was commissioned by the Irish government in 1924 as a gift to the League of Nations in Geneva. However, the work, with its sensuous imagery and perceived nudity in one of the scenes, was deemed too risqué by the conservative Irish Free State government under W.T. Cosgrave. The commission was ultimately rejected, causing a scandal and deep disappointment for Clarke. The "Geneva Window," as it became known, was eventually purchased by Thomas Bodkin, a friend of Clarke's, and later acquired by the Wolfsonian-FIU museum in Miami Beach, Florida, where it remains a highlight of their collection. Its exquisite detail, narrative power, and luminous colour make it a masterpiece of the medium.

Other notable stained-glass works include windows for St. Joseph's Church, Terenure, Dublin; St. Michael's Church, Ballinasloe, County Galway; and the Catholic Church in Bewley's Café on Grafton Street, Dublin, depicting scenes from the lives of saints associated with the arts. Each window is a testament to his unique vision and technical brilliance, transforming light into breathtaking narratives of colour and form.

A Visionary Illustrator: The World of Books

Alongside his prodigious output in stained glass, Harry Clarke was a highly sought-after and influential book illustrator. His illustrations are characterized by the same intricate detail, fantastical imagination, and often dark sensibility found in his glasswork. He primarily worked in pen and ink, sometimes with watercolour washes, creating images that are both decorative and deeply narrative.

His first major commission in book illustration was for Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, published by George G. Harrap in 1916. These illustrations, with their delicate lines, whimsical characters, and dreamlike settings, immediately established his reputation. While sharing some common ground with contemporary illustrators of fantasy like Arthur Rackham, with his gnarled trees and goblins, or Edmund Dulac, with his exotic and decorative flair, Clarke's vision was distinctly his own, often hinting at a darker undercurrent beneath the fairy-tale surface. The influence of Kay Nielsen, another Scandinavian illustrator known for his elegant and stylized work, can also be discerned.

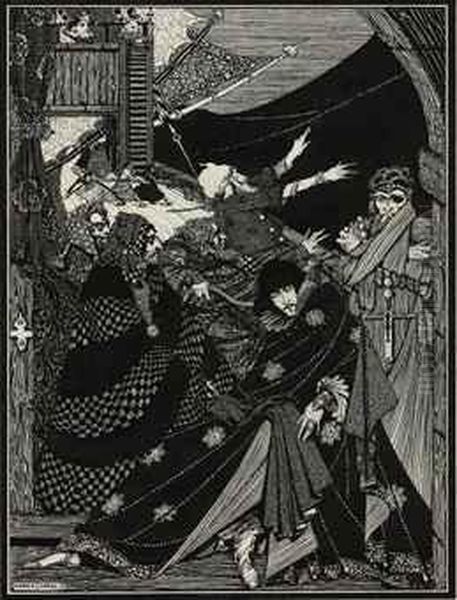

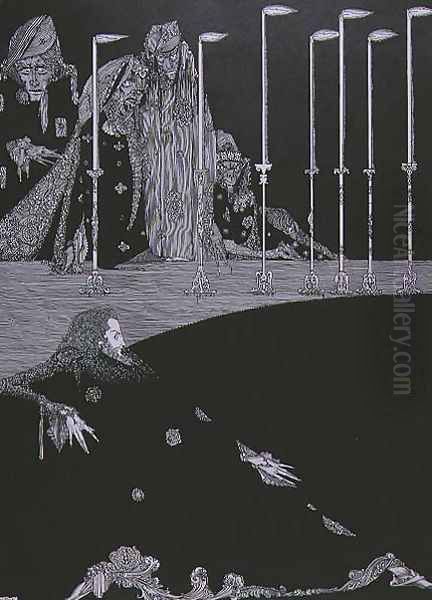

However, it was his illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1919, with a revised and even more striking edition in 1923) that cemented his status as a master of the macabre and the grotesque in illustration. Clarke's images for Poe are unforgettable, perfectly capturing the psychological horror, decadent beauty, and fevered atmosphere of the stories. Intricate, claustrophobic, and filled with elongated, almost skeletal figures, bizarre creatures, and unsettling details, these illustrations are considered by many to be the definitive visual interpretation of Poe's work. They evoke a world of nightmares and obsessions, drawing comparisons to the darker works of Aubrey Beardsley and even the engravings of Gustave Doré for their dramatic intensity.

Clarke also produced remarkable illustrations for other literary works, including:

The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault (1922), where he brought a sophisticated, slightly sinister elegance to classic tales.

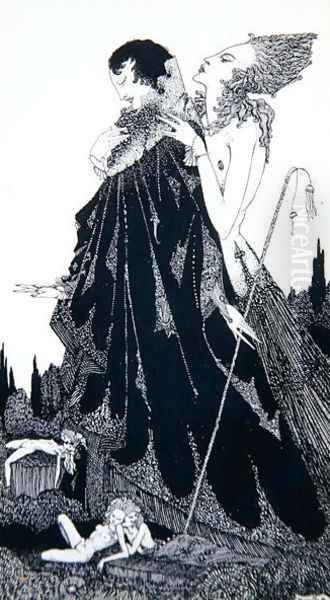

Algernon Charles Swinburne's Selected Poems (1928), for which he created images that mirrored the poet's decadent and often controversial themes.

Goethe's Faust (1925), a limited edition for which he provided haunting and powerful illustrations, particularly notable for their depiction of Mephistopheles and the Walpurgis Night scene.

His book illustrations, like his stained glass, are characterized by an astonishing level of detail. Every inch of the page is often filled with intricate patterns, symbolic elements, and minute figures, inviting close and prolonged scrutiny. He had an uncanny ability to translate the essence of a text into visual form, enhancing its mood and meaning while imposing his own unmistakable artistic personality.

Artistic Circle and Broader Influences

Harry Clarke did not work in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant artistic community in Dublin and was aware of broader European trends. His education at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art connected him with key figures of the Irish Arts and Crafts movement. His teacher, Alfred Ernest Child, was an English stained-glass artist who had come to Ireland to teach at the school and work with Sarah Purser at An Túr Gloine. This connection placed Clarke firmly within the lineage of the modern Irish stained-glass revival.

His contemporaries in Irish stained glass, such as Michael Healy, Wilhelmina Geddes, and Evie Hone, were also producing significant work, each with their own distinct style. While there was undoubtedly a degree of professional rivalry, there was also a shared commitment to elevating the status of stained glass as an art form.

In the realm of illustration, Clarke's work stands alongside that of other great early 20th-century illustrators. While his style was unique, he shared with artists like Rackham, Dulac, and Nielsen a love for fantasy, intricate detail, and the creation of immersive visual worlds. The influence of Aubrey Beardsley is perhaps the most direct and palpable in his black and white work, evident in the elegant, decadent line and the sophisticated use of negative space.

Clarke also travelled, visiting London and Paris, which would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic influences. His visit to see the medieval stained glass of Chartres Cathedral in France, for instance, was a profound experience that reinforced his appreciation for the medium's historical depth and expressive potential. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, also left an imprint, visible in the romantic intensity, medievalism, and attention to decorative detail found in some of Clarke's work.

Personal Life, Relentless Work, and Declining Health

Harry Clarke was known for his intense dedication to his art. He was a prodigious worker, often pushing himself to the limits to meet commissions for both stained glass and illustration. This relentless pace, coupled with a possible predisposition to respiratory illness (his brother Walter also suffered from lung problems), began to take a toll on his health.

He married Margaret Crilly in 1914, and she was not only his wife and the mother of his children (Michael, David, and Ann) but also an artist in her own right. She provided support and understanding, though his demanding work schedule and later, his illness, undoubtedly placed strains on their family life.

By the late 1920s, Clarke's health was in serious decline. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis, a devastating disease at the time with limited treatment options. Despite his failing strength, he continued to work, driven by an unyielding creative urge and the need to provide for his family.

Final Years and Premature Death

In an attempt to recover his health, Harry Clarke travelled to Davos, Switzerland, a well-known sanatorium location for tuberculosis patients, in 1929. He continued to design and correspond about his work from his sickbed, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to his art even as his physical strength waned.

Despite the medical care and the Alpine air, his condition did not improve. Harry Clarke died on January 6, 1931, in Chur, Switzerland, while attempting to return to Ireland. He was only 41 years old. Tragically, due to a misunderstanding of Swiss burial laws which required a permanent marker for a grave to be maintained, his remains were later exhumed and reinterred in a communal grave when no such marker was provided in time by his family, who were grieving and dealing with complex arrangements from afar. This sad postscript meant that his final resting place was lost.

Legacy and Enduring Fascination

Despite his short life, Harry Clarke left behind an extraordinary body of work that continues to be celebrated for its technical brilliance, imaginative power, and unique aesthetic. He is considered one of Ireland's most important artists of the 20th century and a key figure in the final flowering of the Art Nouveau style, as well as a significant Symbolist artist.

His stained-glass windows adorn churches and institutions across Ireland and further afield, captivating viewers with their luminous colours and intricate narratives. They represent a high point in the Irish Arts and Crafts movement and demonstrate the expressive potential of the medium when wielded by a master. His influence on subsequent generations of stained-glass artists in Ireland has been considerable.

His book illustrations, particularly for Poe and Andersen, remain iconic and are frequently reprinted. They have introduced generations of readers to his distinctive visual world and have influenced countless illustrators and graphic artists drawn to the fantastical, the macabre, and the exquisitely detailed. The "dazzling darkness" of his imagery, its ability to be both beautiful and unsettling, holds a particular fascination.

Exhibitions of his work continue to draw large crowds, and scholarly interest in his life and art remains strong. In 2019, a new bridge over the River Liffey in Dublin was named the Harry Clarke Bridge in his honour, a testament to his enduring importance in Irish cultural heritage.

Harry Clarke's art transports us to a world of dreams and nightmares, of saints and sinners, of ethereal beauty and grotesque charm. His ability to fuse meticulous craftsmanship with a visionary imagination resulted in works that are both timeless and utterly distinctive, securing his place as a unique and unforgettable figure in the history of art.