Arthur Hughes (1832-1915) stands as a significant yet often gentle figure within the vibrant landscape of Victorian art. A painter and illustrator closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though never a formal member, Hughes carved a unique niche for himself with works characterized by their delicate beauty, emotional depth, and meticulous detail. His art, steeped in literary and romantic themes, offers a poignant reflection on love, loss, nature, and the passage of time, resonating with audiences through its combination of technical skill and heartfelt sensitivity. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist whose quiet dedication produced some of the most evocative images of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

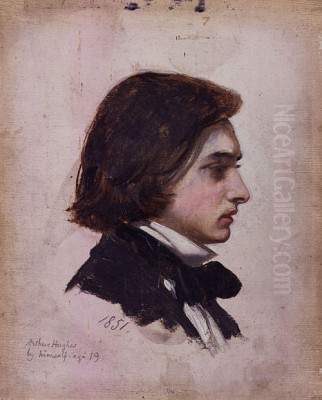

Born in London on January 27, 1832, Arthur Hughes displayed artistic inclinations from a young age. His formal training began in 1846 when he enrolled at the School of Design at Somerset House, studying under Alfred Stevens. The following year, he progressed to the Antique Schools of the Royal Academy of Arts. It was during this formative period that the currents of artistic change were beginning to stir in London, particularly with the emergence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848.

Hughes quickly absorbed the revolutionary ideas circulating within the London art scene. He encountered the Pre-Raphaelite journal, The Germ, and was profoundly influenced by the group's emphasis on truth to nature, vibrant colour, intricate detail, and serious, often morally charged, subject matter. His first major painting, Musidora, based on a theme from James Thomson's poem "The Seasons," was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, marking the public debut of a promising young talent already aligning himself with new artistic directions.

Embracing the Pre-Raphaelite Spirit

While Arthur Hughes never officially joined the seven-member Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his artistic philosophy and output became deeply intertwined with their ideals. He formed close friendships with key figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Ford Madox Brown, who acted as a mentor figure to the younger artists. Hughes embraced the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to rejecting the perceived academic slush and Mannerist distortions derived from followers of Raphael, seeking instead the perceived purity and intensity of early Italian art.

This influence manifested clearly in Hughes's technique. He adopted the practice of painting on a wet white ground to achieve luminous, jewel-like colours. His attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of natural elements like foliage and flowers, became a hallmark of his style. He shared the Pre-Raphaelites' love for literary sources, drawing inspiration from Shakespeare, Keats, Tennyson, and contemporary poets, as well as biblical narratives and medieval legends. His work, however, often possessed a gentler, more melancholic, and less confrontational tone than that of some of his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries.

Signature Style: Colour, Emotion, and Detail

Arthur Hughes developed a distinctive artistic voice characterized by a delicate sensibility, a penchant for romantic and often poignant themes, and a masterful handling of colour and light. His paintings frequently explore themes of love – youthful, unrequited, enduring, or lost – often set against meticulously rendered natural backdrops that underscore the emotional narrative. The transience of beauty and the bittersweet nature of memory are recurring motifs in his work.

His colour palettes are typically rich and vibrant, yet harmoniously balanced. He excelled at capturing specific effects of light, favouring the soft glow of twilight or the dappled sunlight filtering through leaves, which added to the poetic and often dreamlike atmosphere of his scenes. Hughes possessed a remarkable ability to convey subtle emotions through the postures, gestures, and facial expressions of his figures, inviting empathy from the viewer. His compositions are carefully constructed, guiding the eye through intricate details that enrich the central theme. This combination of technical precision and emotional resonance defines his unique contribution to the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

Masterworks of Tender Feeling

Throughout his long career, Arthur Hughes produced several paintings that have become iconic representations of the Pre-Raphaelite ethos, imbued with his characteristic sensitivity.

Ophelia

Hughes painted two significant versions of Ophelia, a subject also famously tackled by John Everett Millais. His first, smaller version (c. 1851-53), predates Millais's masterpiece and depicts Ophelia seated by the stream before her demise, weaving garlands. The later, larger version (1865) shows her already in the water, clutching flowers, her expression one of ethereal detachment rather than acute distress. Both works showcase Hughes's skill in rendering foliage and water, creating a scene of tragic beauty that focuses on pathos and vulnerability, capturing the fragility central to Shakespeare's character.

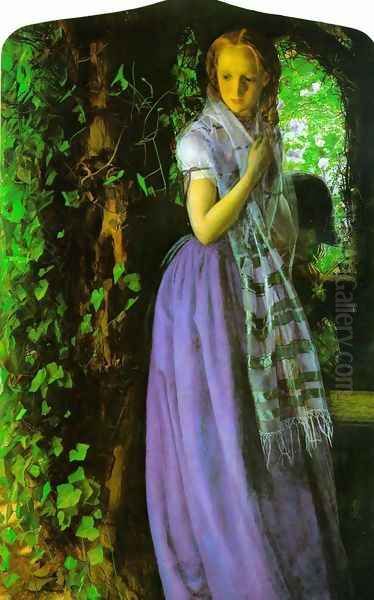

April Love

Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, April Love is perhaps Hughes's most celebrated work. Inspired by lines from Tennyson's poem "The Miller's Daughter," it depicts a young woman standing in the dappled shade of an ivy-covered arbour, her head bowed as fallen petals lie at her feet. A male figure, presumably her lover, is partially visible in the background shadows. The painting beautifully captures the bittersweetness of young love, hinting at a lovers' quarrel or the fragile, fleeting nature of spring and youthful passion. The meticulous rendering of the ivy leaves and the subtle play of light and shadow are exemplary of Hughes's style. The influential critic John Ruskin praised the work for its delicate execution and tender sentiment.

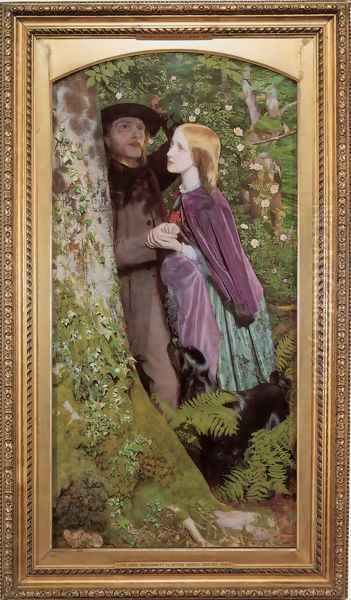

The Long Engagement

Another exploration of love and time, The Long Engagement (c. 1854-59) portrays a young curate and his fiancée in a woodland setting. The woman leans against a tree trunk where the name "Amy" has been carved years earlier, now almost obscured by encroaching ivy, symbolizing the long passage of their engagement, likely prolonged by the curate's modest financial means. The painting speaks to themes of patience, fidelity, and the social constraints faced by many Victorian couples. The detailed depiction of the natural setting, particularly the relentless ivy, serves as a visual metaphor for the slow crawl of time and the endurance of their bond.

Home from the Sea

This poignant painting from 1863 depicts a young sailor boy, returned from sea, weeping at the grave of his mother in a coastal churchyard. The raw emotion of the scene is palpable, conveyed through the boy's posture and the desolate beauty of the setting sun over the water. Home from the Sea is a powerful meditation on loss, grief, and the harsh realities that could interrupt family life. It showcases Hughes's ability to tackle deeply emotional subjects with sincerity and restraint, avoiding overt melodrama while maximizing impact.

The Eve of St. Agnes

Inspired by John Keats's romantic poem, Hughes created several works related to The Eve of St. Agnes. His most famous painting on this theme (1856) depicts the lovers Madeline and Porphyro escaping into the stormy night. The scene is filled with dramatic tension and romantic atmosphere, enhanced by the rich colours, detailed medieval setting, and the dynamic interplay of light and shadow. It exemplifies Hughes's talent for translating literary narratives into compelling visual form, capturing the poem's blend of sensuality, danger, and enchantment.

A Prolific and Sensitive Illustrator

Beyond his easel paintings, Arthur Hughes was one of the most accomplished and sought-after illustrators of the Victorian era. His delicate drawing style, imaginative flair, and sensitivity to text made him particularly suited to illustrating children's literature, poetry, and fantasy. He contributed significantly to the "Golden Age" of British illustration during the 1860s and beyond.

His most famous illustrative collaborations were with the author George MacDonald. Hughes provided enchanting illustrations for MacDonald's fairy tales At the Back of the North Wind (serialized 1868-70) and The Princess and the Goblin (1872), perfectly capturing the blend of wonder, morality, and gentle mysticism in MacDonald's writing. He also illustrated MacDonald's adult novel Phantastes. Another significant collaboration was with the poet Christina Rossetti, for whom he illustrated the delightful Sing-Song: A Nursery Rhyme Book (1872). His charming and often whimsical drawings complemented Rossetti's verses beautifully.

Hughes also contributed illustrations to popular periodicals of the day, including Good Words and Good Words for the Young. His work in black and white demonstrated the same attention to detail, emotional nuance, and compositional skill found in his paintings. His illustrations played a crucial role in shaping the visual culture of the period and remain highly regarded for their artistry and sympathetic interpretation of literary texts.

Personal Life: Modesty and Family

Arthur Hughes's personal life seems to have been characterized by a quiet domesticity and a notably modest disposition. In 1855, he married Tryphena Foord, who occasionally served as a model for his paintings (she is believed to be the model for the female figure in April Love). The couple enjoyed a long and apparently happy marriage, raising a family of several children (sources vary between five and six). They eventually settled in Kew Green, then on the outskirts of London.

Contemporaries described Hughes as shy, gentle, and somewhat self-effacing. Unlike some of his more flamboyant peers, he did not actively seek the limelight or engage heavily in the social politics of the art world. This inherent modesty may have contributed to his struggles for recognition within the formal structures of the Royal Academy, where he sometimes felt his works were poorly hung or unfairly judged. Despite exhibiting regularly, he was never elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), a source of some disappointment.

Family responsibilities also impacted his career. Like many artists of the era, the need to provide a steady income led him to dedicate significant time to illustration, which was often more reliably remunerative than speculative easel painting. The death of his daughter, Elizabeth, in later life also brought personal sorrow and practical burdens, as he took on the task of managing her affairs and unfinished artistic work. His life suggests a man deeply committed to both his family and his art, navigating the challenges of balancing personal obligations with creative pursuits.

Collaborations and the Wider Artistic Circle

Hughes's career was interwoven with the activities of his Pre-Raphaelite friends and the broader Victorian art scene. His most notable collaborative project was the decoration of the Oxford Union debating hall in 1857. Led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, this ambitious but technically flawed project involved several young artists painting murals based on Arthurian legends directly onto the walls. Hughes contributed a panel depicting Arthur's Sleep (The Passing of Arthur).

The Oxford Union project brought Hughes into close working contact with William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, Val Prinsep, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, and John Hungerford Pollen. This shared experience fostered camaraderie and artistic exchange among this group, who represented a "second wave" of Pre-Raphaelitism, moving towards more decorative and medievalizing styles that would eventually feed into the Arts and Crafts movement.

Beyond this core group, Hughes moved within a wider circle that included the original PRB members James Collinson and the sculptor Thomas Woolner, as well as the critic Frederic George Stephens. He knew Walter Deverell, another talented young painter associated with the PRB who died tragically young. While his style differed significantly, he was also contemporary to major figures of the Victorian art establishment like Frederic Leighton and George Frederic Watts, whose more classical or allegorical approaches provided a contrast to the intense naturalism and literary focus of the Pre-Raphaelites. Hughes's career thus unfolded within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

Arthur Hughes continued to paint and illustrate throughout his life, though his most influential and celebrated works largely date from the 1850s and 1860s. He maintained his characteristic style, focusing on themes of romance, nature, and childhood. While public taste began to shift away from Pre-Raphaelitism towards Aestheticism and later Impressionism, Hughes remained steadfast in his artistic vision. He continued to exhibit, though perhaps less prominently than in his youth.

He passed away at his home in Kew Green on December 22, 1915, at the age of 83. By the time of his death, his style might have seemed somewhat old-fashioned to proponents of modern art movements. However, the 20th century saw periodic revivals of interest in Victorian art, and Hughes's reputation has steadily grown. He is now recognized as one of the most appealing and accomplished artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

His works are held in major public collections, primarily in the United Kingdom. Tate Britain holds key paintings including April Love and The Eve of St. Agnes. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford houses Home from the Sea and other works. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, a significant repository of Pre-Raphaelite art, also features paintings by Hughes, as does the National Museum Wales in Cardiff. His illustrations continue to be admired and reproduced, ensuring his presence in the realms of both fine art and book history. His legacy lies in his unique ability to infuse the detailed realism of Pre-Raphaelitism with a tender, lyrical, and deeply human emotional quality.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Arthur Hughes

Arthur Hughes occupies a distinctive place in the history of 19th-century British art. As an artist closely aligned with the Pre-Raphaelites yet possessing his own gentle and melancholic voice, he created a body of work that continues to captivate viewers with its technical finesse, emotional resonance, and romantic sensibility. His paintings, often exploring the complexities of love, the beauty of nature, and the poignancy of passing time, offer intimate glimpses into the Victorian heart. Equally significant was his contribution as an illustrator, where his imaginative drawings brought classic texts to life for generations of readers. Though perhaps overshadowed during his lifetime by more assertive personalities, Arthur Hughes's quiet dedication to his craft resulted in art of enduring beauty and profound feeling, securing his position as a cherished figure of the Victorian era.