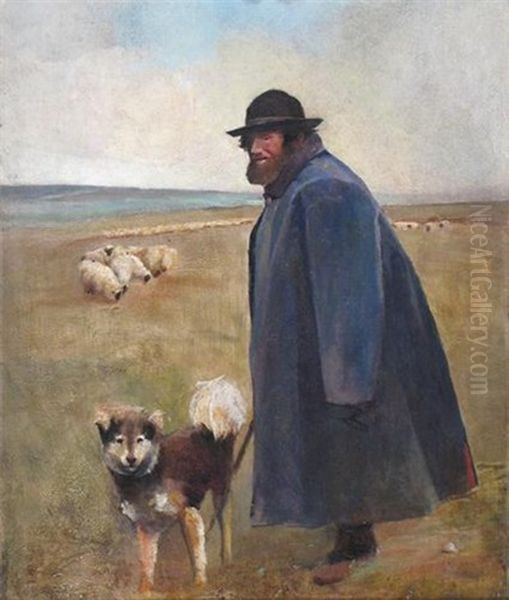

Harry Fidler stands as a distinctive figure in British art from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in 1856 and passing away in 1935, his life spanned a period of significant change, both in society and in the art world. He emerged as a notable Post-Impressionist painter, celebrated for his vigorous depictions of English agricultural life, particularly his dynamic portrayals of working horses. Fidler developed a unique and recognizable style, characterized by a bold, impasto technique, often applied with what contemporaries described as a "long-arm" method, lending his canvases a textured vibrancy and energetic immediacy. His work captures the essence of the countryside before the widespread mechanization of farming transformed it forever.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Harry Fidler was born into the rural heartland of England, specifically in Teffont Magna, Wiltshire, in 1856. His upbringing was deeply rooted in the agricultural world he would later depict with such passion. He was one of ten children born to a farming family, an environment that undoubtedly instilled in him a profound understanding and appreciation of the rhythms of rural existence, the toil of the land, and the essential role of animals, especially the powerful draught horses that feature so prominently in his oeuvre. This direct, lived experience provided a foundation of authenticity that resonates throughout his artistic career.

Unlike many artists who follow a predetermined path from a young age, Fidler's formal art education began later in life, suggesting a mature decision to pursue his calling. He enrolled at the renowned Herkomer School of Art in Bushey, Hertfordshire. Founded by the eminent Victorian artist Sir Hubert von Herkomer, the school was known for its progressive approach, attracting students keen on developing individual styles rather than adhering strictly to academic convention. Studying in this environment likely encouraged Fidler's own move towards a more expressive, less conventional technique.

The Herkomer School, under the guidance of Sir Hubert von Herkomer himself, fostered a spirit of realism often combined with an appreciation for painterly technique. Herkomer, a versatile artist proficient in painting, printmaking, and even early filmmaking, encouraged observation and a connection to contemporary life. Fidler's time there would have exposed him to various artistic currents and provided him with the technical grounding necessary to develop his distinctive approach. It was a crucial period of formation, setting the stage for his emergence onto the London art scene.

The Development of a Unique Style

Fidler’s artistic voice truly found its expression in his unique painting technique. He became known for his use of impasto – applying paint thickly, often straight from the tube, so that brushstrokes are visible and create a textured surface. This method added a physical dimension to his work, enhancing the sense of energy and movement, particularly suitable for his subjects of powerful horses and dynamic farm activities. The description of his "long-arm" technique suggests a very physical, gestural approach to painting, perhaps using long brushes or standing back from the canvas to apply strokes with broad, sweeping movements.

This technique aligns him broadly with Post-Impressionist tendencies, although his style remained distinctly his own. Unlike the broken colour and focus on fleeting light effects typical of French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Fidler's work often emphasized form and structure through thick paint, while still capturing the atmosphere and light of the English countryside. His colour palette could be vibrant, reflecting the richness of the rural landscape, but often retained an earthy quality grounded in the reality of his subject matter.

His commitment to this bold, textured style set him apart from the smoother, more detailed finish favoured by many traditional Victorian and Edwardian painters. It allowed him to convey the raw energy of his subjects – the straining muscles of a horse, the churned earth of a ploughed field, the bustling activity of harvest time. This expressive handling of paint became his signature, making his works immediately recognizable and contributing significantly to their appeal. He wasn't merely documenting scenes; he was interpreting their inherent vitality through the very substance of his medium.

Subject Matter: The Heartbeat of the Farm

The core of Harry Fidler's artistic output lies in his depiction of English farm life. Growing up on a farm gave him an intimate knowledge of this world, and his paintings reflect a deep empathy and understanding of his subjects. He didn't romanticize rural labour in an overly sentimental way; rather, he captured its vigour, its challenges, and its inherent dignity. His canvases are often populated with scenes of ploughing, harrowing, harvesting, and carting – the essential tasks that defined the agricultural year.

Central to many of these scenes are the magnificent heavy horses – Shires, Clydesdales, or Suffolk Punches – the primary source of power on farms before the tractor age. Fidler painted these animals with remarkable dynamism and understanding, capturing their strength, their patient endurance, and their vital partnership with the farm workers. He depicted them in action, muscles straining as they pulled the plough through heavy soil or hauled loaded wagons. These are not just animal portraits; they are celebrations of working animals as integral parts of the rural economy and landscape.

Works such as Clearing the Potato Patch, held in The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, exemplify his focus. Such paintings often convey a strong sense of place and atmosphere – the feel of the weather, the texture of the soil, the sounds and smells of the farm. Fidler’s commitment to these themes places him alongside other British artists who found inspiration in rural life, such as George Clausen, known for his depictions of field labourers, or Lucy Kemp-Welch, who also specialized in painting horses, albeit often in a different style. However, Fidler's robust technique gave his interpretations a unique forcefulness. His connection to the land was palpable in his work.

Career, Exhibitions, and Recognition

Fidler began to establish his reputation in the London art world in the early 1890s. A significant milestone occurred in 1891 when he first exhibited his work at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. This marked his entry into the mainstream British art scene and provided a crucial platform for showcasing his talent. Gaining acceptance at the RA was a key step for any aspiring artist seeking recognition during this period.

His association with major art societies grew over the following years. From 1894, he began exhibiting with the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA), an important exhibiting body that offered an alternative to the Royal Academy. His consistent participation and the quality of his work led to his election as a full member of the RBA, a significant professional acknowledgment (sources vary slightly on the exact year, sometimes cited as 1901 or later). He also exhibited with the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI), further cementing his position within the circles of professional painters in London.

Fidler's work was not confined to London or Britain. He exhibited internationally, including at the Paris Salon, the renowned official art exhibition in France, indicating his ambition and the appeal of his work beyond British shores. He also participated in exhibitions further afield, with mentions of his work being shown and appreciated in South Africa. A notable event in his exhibition history was a two-person show held alongside the artist William Lee-Hankey, a contemporary known for his paintings and etchings often depicting coastal and rural life. Such collaborations and diverse exhibition venues helped broaden his audience and critical reception. His works were also handled by commercial venues like the Goupil Gallery.

The Artist's Circle and Contemporaries

Harry Fidler did not work in isolation. His artistic life was intertwined with that of his family. In 1919, he married Laura Clunas, who was herself an accomplished artist. Laura Fidler often painted similar subjects to her husband, sometimes employing a comparable vigorous style. They shared a studio environment, first in Salisbury and later settling in Andover, Hampshire. This shared artistic practice likely created a supportive and stimulating domestic environment. His brother, Gideon Fidler, was also a painter, suggesting a strong artistic inclination within the family.

Beyond his immediate family, Fidler was part of a broader network of artists. His time at Herkomer's school would have connected him with fellow students and the influential circle around Sir Hubert von Herkomer. Artists like Lucy Kemp-Welch, also known for her powerful horse paintings, were associated with Bushey. While direct evidence of close friendships is limited in the provided snippets, Fidler exhibited alongside many prominent artists of his day.

His contemporaries included figures associated with various movements. The Newlyn School artists, such as Stanhope Forbes, were also focused on depicting rural and coastal life with a degree of realism and attention to light, though often with a different stylistic approach. British Impressionists like Philip Wilson Steer explored light and atmosphere, while Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group focused more on urban realism. Although perhaps not a direct influence, the work of earlier painters of rural life, like the French artist Jean-François Millet, provided a historical context for the dignity of agricultural labour in art. Fidler's unique contribution was his specific focus on the heavy horse and his energetic, impasto technique. Some sources mention Tom Mostyn and Arnesby Brown, known for their landscape and figure painting, as potentially being associated with Fidler or Herkomer's influence, representing the younger generation of artists active during his career. Even major figures like Sir Alfred Munnings, famous for his equestrian art, or William Nicholson, known for his distinctively modern still lifes and portraits, were contemporaries whose work provides contrast and context to Fidler's specific niche.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

After his marriage to Laura Clunas in 1919, Harry Fidler continued to paint actively. The couple's move to Andover provided a base in the Hampshire countryside, allowing him to remain close to the rural subjects that inspired him throughout his career. He continued exhibiting his work, maintaining his presence in the art world well into the early twentieth century. His dedication to his craft remained steadfast throughout his life.

Harry Fidler passed away in 1935 at the age of 79. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its honesty, vigour, and unique style. His paintings serve as valuable historical documents, capturing a way of life centred around animal power and manual labour that was rapidly disappearing even during his later years. His focus on the heavy horse, rendered with such energy and empathy, remains a particularly strong element of his legacy.

Today, Fidler's works are held in several public collections in the UK, including The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery (Stoke-on-Trent) which holds Clearing the Potato Patch. His paintings also appear regularly on the art market, often commanding significant prices, demonstrating their continued appeal to collectors. For instance, his large work Harvesting has achieved substantial figures at auction, reflecting the high regard in which his art is held. This market appreciation underscores his status as an important British painter of his generation.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Voice in British Art

Harry Fidler carved out a unique place in British art history through his unwavering focus on the agricultural life of England and his distinctive, energetic painting style. Rooted in his own rural upbringing and honed through formal training, his approach combined Post-Impressionist sensibilities with a deeply personal connection to his subject matter. The thick impasto, the dynamic compositions, and the powerful presence of working horses define his contribution.

He successfully navigated the professional art world, exhibiting widely at major institutions like the Royal Academy and the Royal Society of British Artists, and gaining recognition both at home and abroad. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his European contemporaries, Fidler developed a highly individual and expressive visual language that perfectly suited his chosen themes. His paintings offer more than just depictions of farm scenes; they convey the very pulse of rural labour and the enduring spirit of the English countryside.

His legacy endures through his paintings, which continue to resonate with viewers for their authenticity, their textural richness, and their celebration of a bygone era of agricultural life. Harry Fidler remains a significant figure, remembered as a powerful painter of the land and its working animals, a true chronicler of the soil rendered in bold, unforgettable strokes. His work stands as a testament to the enduring power of observing and interpreting the world directly through the expressive potential of paint.