Harry Hall stands as one of the preeminent figures in British sporting art, particularly renowned for his masterful portraits of racehorses during the Victorian era. Active from the late 1830s until his death in 1882, Hall created an extensive and invaluable visual record of the champions of the British turf. His work not only captured the physical likeness of these celebrated animals but also reflected the passion and prestige associated with horse racing in 19th-century Britain. His paintings were highly sought after by owners, breeders, and enthusiasts, and through widespread engravings, his images reached an even broader audience, cementing the fame of the horses he depicted.

Hall's contribution extends beyond mere representation; his meticulous attention to anatomical detail and his ability to convey the distinct character and conformation of each horse made his work essential for the historical documentation of thoroughbred bloodlines. He succeeded artists like John Frederick Herring Sr. as the go-to painter for classic winners, establishing a distinct style that balanced accuracy with artistic sensibility. His legacy endures through the numerous paintings held in public and private collections, offering a vivid window into the golden age of British horse racing.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Harry Hall was born in Cambridge, England, in 1814. While details of his earliest years and formal training are somewhat scarce compared to some contemporaries, it is evident that he developed considerable artistic skill early on. Cambridge itself, while increasingly known for its university, was situated in a region with strong ties to horse racing, particularly Newmarket, the emerging headquarters of the sport, located just a few miles away. This proximity may have fostered an early interest in equestrian subjects.

By the late 1830s, Hall had moved to London to pursue his artistic career, immersing himself in the city's vibrant art scene. He made his public debut in 1838, exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. This marked the beginning of a long exhibiting career, with his works also appearing at other important venues such as the British Institution and the Society of British Artists (later the Royal Society of British Artists). These early exhibitions likely included a mix of subjects, but his talent for animal painting, especially horses, quickly became apparent.

Some accounts suggest Hall may have received guidance or been influenced by established animal painters of the time. Abraham Cooper (1787-1868), a respected Royal Academician known for his battle scenes and animal subjects, including horses, is sometimes mentioned as a possible influence or even tutor. Cooper's detailed style and focus on anatomical accuracy certainly resonate with Hall's later work. Regardless of specific tutelage, Hall rapidly honed his skills, particularly in the demanding genre of equestrian portraiture.

His early London years were crucial for establishing his reputation. Exhibiting regularly brought his work to the attention of potential patrons, including the wealthy landowners and aristocrats who dominated the racing world. The meticulous quality of his painting and his evident understanding of equine anatomy set him apart, paving the way for his specialization in depicting the stars of the turf.

The Move to Newmarket and Rise to Prominence

A pivotal moment in Harry Hall's career came around 1844-1846 when he relocated from London to Newmarket. This Suffolk town was, and remains, the undisputed centre of British horseracing – home to the Jockey Club, major training stables, studs, and two of the country's most important racecourses. Moving to Newmarket placed Hall directly at the heart of his subject matter and clientele.

Living and working in Newmarket provided Hall with unparalleled access to the finest racehorses, trainers, jockeys, and owners. He could observe the horses daily, study their conformation and temperament, and capture them at the peak of their condition. This proximity undoubtedly enhanced the authenticity and accuracy that became hallmarks of his work. He became the town's resident master painter of thoroughbreds.

His reputation solidified rapidly during this period. Owners of classic winners, particularly the winners of the Derby, Oaks, St Leger, 2000 Guineas, and 1000 Guineas, frequently commissioned Hall to paint portraits of their champions. These paintings served not only as records of famous victories but also as status symbols, celebrating the owner's success and the horse's prowess. Hall effectively became the successor to John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865), who had previously dominated the field of racehorse portraiture but whose output was declining in his later years.

Hall's Newmarket studio became a hub for the racing elite. His ability to deliver accurate, detailed, and aesthetically pleasing portraits ensured a steady stream of commissions. He developed strong working relationships with prominent figures in the racing world, which further cemented his position as the leading equestrian artist of his generation. His presence in Newmarket for nearly four decades underscores the town's central importance to his life and art.

Artistic Style and Technique

Harry Hall developed a distinctive and highly refined style perfectly suited to equestrian portraiture. His primary focus was on achieving an accurate and detailed representation of the individual horse. He paid meticulous attention to anatomical correctness, capturing the specific conformation, musculature, and proportions that defined each champion thoroughbred. This accuracy was highly valued by his patrons, who were often knowledgeable breeders and owners concerned with bloodlines and physical attributes.

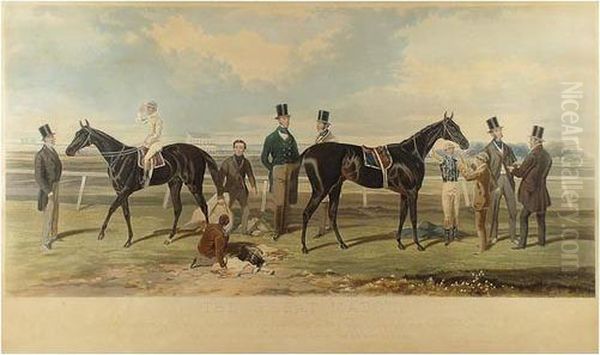

Hall typically depicted horses in profile or near-profile, often standing still in a landscape or stable setting. This conventional pose allowed for a clear view of the horse's conformation. While perhaps less dynamic than the action scenes favoured by artists like Henry Thomas Alken (1785-1851) or James Pollard (1792-1867), Hall's approach emphasized the horse's physical presence and individual characteristics. He rendered the sheen of the horse's coat, the details of the tack (saddles and bridles), and the texture of the surrounding environment with painstaking care.

His landscapes, while secondary to the equine subject, were usually competently handled, often depicting recognizable locations like Newmarket Heath or racecourse settings. Figures, such as jockeys, trainers, or owners, were often included, typically rendered with less detail than the horse itself but adding context and scale. Famous jockeys like Nat Flatman, John Barham Day, and John Day Jr. appear in many of his works, often depicted in the owner's racing colours.

Compared to the great innovator George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose work combined scientific observation with classical composition, Hall's style was perhaps more straightforwardly documentary, reflecting Victorian tastes for detailed realism. Unlike Ben Marshall (1768-1835), known for his more painterly and atmospheric approach, Hall maintained a consistently high level of finish. His work provided a reliable and elegant record, perfectly meeting the demands of his patrons for faithful representations of their prized animals. He worked primarily in oils on canvas, producing works of varying sizes, from modest studies to large-scale commemorative portraits.

Major Works and Celebrated Subjects

Harry Hall's extensive oeuvre includes portraits of many of the most famous racehorses of the mid-to-late 19th century. His commissions often followed major victories in the Classic races, making his work a veritable gallery of turf legends.

One of his most well-known later works depicts "Kisber", the winner of the 1876 Epsom Derby. The painting, typical of his style, shows the horse in profile, attended by a figure, likely his trainer Joseph Hayhoe, set against a subtle landscape background. The focus is entirely on the horse's powerful physique and dark coat, rendered with Hall's characteristic precision. This work exemplifies his mature style and his role in documenting Derby winners.

Earlier in his career, he painted "Sir Tatton Sykes", winner of the 1846 St Leger Stakes. This horse was named after a prominent Yorkshire landowner and sportsman, Sir Tatton Sykes, 4th Baronet, himself an important figure painted by artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence. Hall's portrait of the horse likely commemorated its classic victory and would have been highly prized by its owner, William Scott.

Hall painted "Crucifix" (foaled 1837), an exceptional filly who won the 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, and the Oaks in 1840, remaining undefeated in her career. His portrait captures her elegance and quality, preserving the image of one of the early queens of the turf. Similarly, he depicted "Beeswing" (foaled 1833), a remarkably durable and popular mare who raced until the age of nine, winning numerous Cup races, including the Ascot Gold Cup twice.

The legendary horse "Rataplan" (foaled 1850), known for his stamina and prolific racing career (winning 42 races), was another subject. Hall's portrait would have emphasized the strength and endurance of this crowd favourite, who later became a successful sire. He also painted "Kettledrum", the winner of the 1861 Epsom Derby and Doncaster Cup, capturing another classic champion for posterity.

Hall documented the winners of the Triple Crown, a rare achievement. He painted "West Australian" (foaled 1850), the first horse to win the 2000 Guineas, Epsom Derby, and St Leger Stakes (in 1853). Later, he depicted "Gladiateur" (foaled 1862), the French-bred hero who conquered the English Triple Crown in 1865, a feat that resonated deeply on both sides of the Channel.

Other notable subjects include "Stockwell" (foaled 1849), winner of the St Leger and 2000 Guineas, who became a hugely influential sire known as "The Emperor of Stallions." Hall painted "Blink Bonny" (foaled 1854), a filly who achieved the rare feat of winning both the Derby and the Oaks in 1857. He also captured the famous rivalry between "The Flying Dutchman" (1849 Derby & St Leger winner) and "Voltigeur" (1850 Derby & St Leger winner), possibly depicting them individually around the time of their famous Great Match at York in 1851.

His portraits often included famous jockeys associated with the horses, such as Nat Flatman, John Barham Day, John Day Jr., George Fordham, and Jem Robinson, usually depicted wearing the specific racing silks (colours) of the horse's owner. These details added another layer of historical accuracy and interest to the paintings.

Engravings and Publications: Reaching a Wider Audience

While Harry Hall's original oil paintings were commissioned by wealthy patrons, his work reached a much wider audience through engravings. During the 19th century, sporting publications flourished, catering to the growing public interest in horse racing, hunting, and other field sports. Hall became a key contributor to several of the most prominent periodicals.

He provided numerous paintings that were subsequently translated into engravings for publications like The Sporting Magazine, The Illustrated London News, The Field, and The Sporting Review. These journals featured high-quality prints of recent classic winners and other notable horses, often accompanied by articles detailing their pedigrees, race records, and ownership. Hall's accurate and detailed portraits were ideal for this purpose.

The process typically involved skilled engravers, such as John Harris, Charles Hunt, or William Summers, meticulously copying Hall's paintings onto metal plates (usually steel or copper) to create printable images. These engravings faithfully reproduced the composition and details of Hall's originals, allowing thousands of readers to see representations of the day's equine stars. This dissemination played a crucial role in building the fame of horses like Kisber, Rataplan, or Blink Bonny beyond the racecourse attendees.

Hall's association with Tattersalls, the famous bloodstock auctioneers, was also significant. He is often described as having been their chief artist for a period. Tattersalls commissioned portraits of important horses, perhaps for their own records or publications, further solidifying Hall's central role in the visual culture of the racing industry. His work for these publications and institutions ensured that his depictions became the definitive images of many celebrated thoroughbreds.

These engravings are now valuable historical documents in their own right, offering insights into 19th-century racing history and the popular visual culture surrounding it. They underscore Hall's importance not just as a painter for the elite but as a key figure in shaping the public image of the sport and its champions. The demand for these prints also provided Hall with a steady source of income and recognition beyond individual painting commissions.

Context: Equestrian Art in Victorian Britain

Harry Hall worked within a long and distinguished tradition of British sporting art, which had risen to prominence in the 18th century with artists like George Stubbs and Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807). These earlier masters established conventions for horse portraiture, combining anatomical study with artistic composition. By the early 19th century, artists like Ben Marshall, James Ward (1769-1859), and Abraham Cooper continued this tradition, adapting it to the changing tastes and demands of patrons.

Hall's immediate predecessor in terms of popularity for commissioned racehorse portraits was John Frederick Herring Sr. Herring dominated the field in the 1820s, 30s, and early 40s, painting numerous Derby and St Leger winners with a detailed, slightly more romantic style than Hall's. As Herring Sr.'s output decreased, Hall effectively took over as the leading painter of classic winners from the mid-1840s onwards. Herring's son, John Frederick Herring Jr. (1820-1907), also painted equestrian scenes, often focusing more on farmyard or coaching subjects, though sometimes tackling racing themes.

Other contemporaries specialized in different aspects of sporting life. Henry Thomas Alken and James Pollard were renowned for their dynamic and often humorous depictions of coaching, hunting, and racing scenes, focusing more on action and narrative than formal portraiture. Charles Cooper Henderson (1803-1877) was another master of coaching scenes. While their styles differed from Hall's, their work collectively reflects the immense popularity of horse-related activities in British society.

The broader context of Victorian art also included Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), the era's most celebrated animal painter. While Landseer was known more for his dramatic depictions of stags, dogs, and lions, often imbued with anthropomorphic sentiment (like his famous "Monarch of the Glen"), his success highlights the high status accorded to animal painting during the period. Hall's work, though focused specifically on the thoroughbred, benefited from this general appreciation for animal subjects.

The immense popularity of horse racing itself during the Victorian era cannot be overstated. It was the "Sport of Kings" but also attracted huge crowds from all social classes, as vividly captured in William Powell Frith's famous painting "The Derby Day" (1858). This widespread interest created a strong market for equestrian art. Wealthy industrialists joined the traditional landed aristocracy in owning racehorses and commissioning portraits, viewing success on the turf as a mark of social standing. Hall's detailed, realistic style perfectly suited this clientele, providing prestigious records of their equine investments and triumphs.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Harry Hall remained active and highly sought after as an equestrian artist throughout his later career, continuing to live and work in Newmarket until his death. He maintained his meticulous style and continued to document the champions of the turf year after year. His output was prolific, reflecting the constant demand for portraits of successful racehorses.

He passed away in Newmarket on April 22, 1882, leaving behind a remarkable body of work that chronicled several decades of British racing history. His death marked the end of an era for a certain style of formal equestrian portraiture, although the tradition continued with later artists adapting to new artistic trends and the advent of photography.

Harry Hall's legacy is significant and multifaceted. Firstly, he created arguably the most comprehensive visual record of mid-to-late 19th-century champion racehorses. His paintings are invaluable historical documents for turf historians, breeders, and enthusiasts, preserving the likenesses of horses whose bloodlines continue to influence the thoroughbred breed today. The accuracy of his depictions provides insights into the conformation and development of the breed over time.

Secondly, his work represents a high point in the tradition of British sporting art. While perhaps lacking the innovative genius of Stubbs or the atmospheric flair of Marshall, Hall achieved a mastery of realistic representation perfectly attuned to his subject and patrons. His paintings are characterized by their technical skill, consistency, and documentary value. He fulfilled the role of chronicler of the turf with unparalleled dedication and proficiency for nearly half a century.

Today, Harry Hall's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections worldwide, including the National Horseracing Museum in Newmarket, the Yale Center for British Art, and various national galleries. His works regularly appear at auction, where they command significant prices, reflecting continued appreciation for his skill and the historical importance of his subjects. The engravings made after his paintings also remain popular collector's items.

Conclusion: Chronicler of Champions

Harry Hall occupies a crucial place in the history of British art, specifically within the specialized genre of equestrian portraiture. For nearly five decades, he dedicated his considerable talents to documenting the elite thoroughbred racehorses of his time. Working primarily from his base in Newmarket, the epicentre of British racing, he produced a vast and remarkably consistent body of work characterized by anatomical accuracy, meticulous detail, and a clear, objective style.

His portraits of Derby winners, St Leger champions, and other celebrated horses like Kisber, Rataplan, West Australian, and Blink Bonny served as vital records for owners and breeders and, through engravings, shaped the public image of these equine athletes. He captured the conformation and character of individual horses with a skill that made him the preeminent painter of choice for commemorating classic victories during the mid-to-late Victorian era.

While working within established conventions, Hall brought a level of precision and dedication to his craft that solidified his reputation. He stands alongside figures like John Frederick Herring Sr. as a defining artist of 19th-century sporting art. His legacy endures not only in the aesthetic appeal of his paintings but also in their invaluable contribution to the historical record of the thoroughbred breed and the rich cultural heritage of horse racing. Harry Hall remains celebrated as a master chronicler of the champions of the Victorian turf.