Harvey Joiner (1852-1932) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in American landscape painting. Active during a transformative period in American art, Joiner carved a niche for himself with his evocative depictions of the woodlands of Indiana and Kentucky. His canvases, often imbued with a palpable sense of atmosphere and a masterful play of light, particularly sunlight filtering through dense canopies of beech and pine, continue to resonate with collectors and art enthusiasts. This exploration delves into the life, artistic development, signature style, key works, and the broader art historical context of Harvey Joiner, an artist who dedicated his career to capturing the subtle beauties of his native landscapes.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born in Charlestown, Indiana, in 1852, Harvey Joiner reportedly displayed an inclination towards art from a very young age. Like many aspiring artists of his generation who lacked immediate access to formal academies, his early artistic endeavors were shaped by practical experience and self-directed learning. The American artistic landscape of the mid-19th century was still developing its own distinct voice, with many artists looking to European traditions while simultaneously seeking to define a uniquely American aesthetic.

By the age of sixteen, Joiner was already venturing out, seeking to make a living through his nascent skills. An interesting, though perhaps apocryphal, anecdote suggests that during this period, he spent time working on riverboats in Louisiana. It is said that he created sketches documenting the African American culture he encountered there, hinting at an early observational acuity and an interest in diverse subjects, even if his later career would focus predominantly on landscapes. This experience, if true, would have exposed him to different environments and human experiences, broadening his visual vocabulary.

A more concrete step in his artistic journey occurred in 1874. In St. Louis, Missouri, a burgeoning city and a gateway to the West, Joiner encountered a German portrait painter named Hoffman. This meeting proved pivotal, as Joiner became Hoffman's student and assistant. Apprenticeship under an established artist was a common path for aspiring painters, providing invaluable hands-on training in technique, material handling, and the business of art. Portraiture was a commercially viable genre, and skills honed in capturing likenesses, understanding anatomy, and managing paint would serve any artist well, regardless of their eventual specialization.

Following this period of tutelage, Joiner, like many artists of the era, likely worked as an itinerant painter. This often involved traveling from town to town, undertaking commissions for portraits, painting signs for businesses, or any other artistic work available. This lifestyle demanded versatility and resilience, but it also provided a deep immersion in the diverse communities and landscapes of the American heartland. It was during these formative years that Joiner would have further developed his technical skills and begun to cultivate his unique artistic vision.

The Transition to Landscape and a Signature Style

While portraiture and commercial work may have provided his initial livelihood, Harvey Joiner's true passion and lasting legacy would be found in landscape painting. He eventually settled and worked primarily in Kentucky and Indiana, regions whose sylvan beauty became the central focus of his art. He developed a particular affinity for depicting the deep woods, with a special emphasis on beech and pine trees, capturing the way sunlight dramatically pierces the dense foliage to illuminate the forest floor.

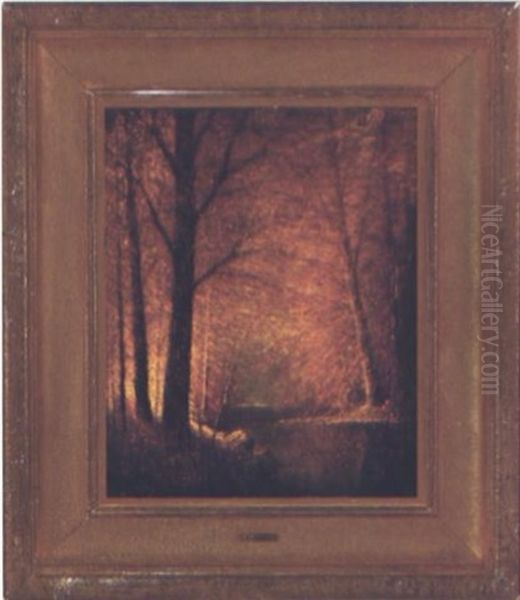

Joiner's preferred medium was oil paint, which allowed him the richness of color and the ability to build up textures necessary to convey the depth and complexity of his woodland scenes. A distinctive characteristic of his work, and indeed his presentation, was the use of dark, often elaborate, shadow box frames. These frames, sometimes described as "deep color shadow box backgrounds," served to enhance the luminosity of his paintings, making the light-filled areas appear even more radiant by contrast. This framing choice was an integral part of the viewing experience he intended, drawing the observer's eye into the heart of the painted scene.

His style can be situated within the broader currents of late 19th and early 20th-century American landscape painting, which saw a shift from the grand, panoramic vistas of the earlier Hudson River School artists like Albert Bierstadt or Frederic Edwin Church towards more intimate, atmospheric, and subjectively rendered scenes. Joiner's work often exhibits qualities associated with Tonalism, an artistic style that emerged in the 1880s, characterized by soft, diffused light, muted palettes, and an emphasis on mood and poetic evocation. Artists like George Inness, Dwight William Tryon, and Alexander Helwig Wyant were key proponents of Tonalism, and while Joiner may not have been a formal adherent, his work shares their concern for capturing the subtle nuances of light and atmosphere.

The influence of the French Barbizon School, with painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, can also be discerned. The Barbizon painters championed a direct engagement with nature, often painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture the fleeting effects of light and weather. Their work, which gained popularity in America, encouraged a more personal and less idealized approach to landscape, a sentiment that resonates in Joiner's intimate woodland interiors.

Themes and Artistic Vision

The recurring themes in Harvey Joiner's oeuvre revolve around the forest. He was particularly adept at capturing the seasonal moods of the woodlands, from the fresh greens of spring to the rich, warm hues of autumn. His paintings often feature paths or rudimentary roads winding through the trees, inviting the viewer to metaphorically enter the scene and explore its depths. These pathways also serve as compositional devices, leading the eye and creating a sense of perspective.

Perhaps the most compelling theme in Joiner's work is the interplay of light and shadow. He masterfully depicted sunlight filtering through leaves, dappling the forest floor, and highlighting the textures of tree bark. This focus on light was not merely representational; it imbued his scenes with a spiritual or emotional quality, transforming ordinary woodland views into spaces of quiet contemplation and natural beauty. His ability to render these effects gave his paintings a dynamic, almost living quality.

While his primary focus was the uninhabited landscape, the human presence was often implied through these paths or the occasional glimpse of a rustic fence. However, the overwhelming impression is one of nature's serene dominance. His work celebrated the quiet majesty of the forests he knew so well, offering an escape from the increasing industrialization and urbanization of American life during his lifetime.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Harvey Joiner's style and thematic concerns:

"Sunlight through Beeches" (c. 1904): This title, or variations like "Sunlight through Pines," encapsulates a signature Joiner subject. Such a work, likely the one dated 1904 and housed in the McClung Museum, would typically depict a dense stand of beech trees, their smooth, grey bark and characteristic leaf structure meticulously rendered. The focal point would be the brilliant sunlight breaking through the canopy, creating pools of light on the forest floor and casting long, intricate shadows. The use of a deep shadow box frame would further accentuate the luminosity within the painting, making the sunlit areas almost glow. The mood would be one of tranquility and the quiet grandeur of nature.

"Through the Oak Tree Road": Mentioned in connection with a 2023 auction, this title suggests a scene where a path or road is framed or dominated by oak trees. Oaks, with their sturdy trunks and distinctive lobed leaves, would offer a different textural quality compared to beeches or pines. Joiner would likely have focused on the play of light through the oak canopy, perhaps highlighting the ruggedness of the bark or the patterns of leaves on the ground. The "road" element implies a human trace, guiding the viewer's eye into the composition and suggesting a journey or passage. A painting with this title, described as 20 x 30 inches and presented in a gilt and gesso frame at a Case Antiques auction, would exemplify his mature style.

"Spring Landscape": A work titled "Spring Landscape," noted as a 22 x 27-inch oil painting formerly in the Katherine Rudolph collection and sold at a HINDMAN auction, would showcase Joiner's ability to capture the specific palette and atmosphere of springtime. This might involve tender new leaves in varying shades of green, perhaps wildflowers dotting the forest floor, and a softer, more diffused light than the stark contrasts often seen in his autumnal or summer scenes. Such a painting would highlight his sensitivity to the changing seasons and their impact on the woodland environment.

"Oil Forest Landscape Painting": This more generic description, often used for his works, points to his consistent engagement with the forest interior. A typical "Oil Forest Landscape Painting" by Joiner would feature a composition drawing the viewer into the woods, sunlight filtering through trees to illuminate a central path or clearing, and a rich, earthy palette. The meticulous rendering of tree forms and foliage, combined with an atmospheric quality, would be characteristic.

These works, and others like them, demonstrate Joiner's consistent artistic vision: to capture the intimate beauty and the dramatic effects of light within the woodlands he knew and loved. His paintings are not just records of specific places but are also meditations on the power and serenity of nature.

Artistic Context and Connections

Harvey Joiner worked during a vibrant period for American art. While he focused on his regional landscapes, he was a contemporary of artists exploring diverse styles and subjects. The aforementioned Tonalists like Inness and Wyant were creating moody, atmospheric landscapes that shared some affinities with Joiner's work. The Hoosier Group, a collective of Indiana artists including T.C. Steele, William Forsyth, J. Ottis Adams, Richard Gruelle, and Otto Stark, were also gaining prominence for their Impressionist-influenced depictions of the Indiana landscape. While Joiner was not formally part of this group, he shared their dedication to capturing the local scenery and undoubtedly contributed to the burgeoning regionalist art movement.

In Kentucky, artists like Paul Sawyier were also known for their landscape paintings, often with an Impressionistic sensibility. Further afield, major figures like Winslow Homer were creating powerful American scenes, though with a different focus on marine subjects and narrative. The celebrated portraitist John Singer Sargent, though working in a vastly different genre and international circles, represented the pinnacle of painterly skill and cosmopolitanism in American art of the era. While direct influence from Sargent on Joiner's woodland scenes is unlikely, the general artistic climate encouraged a high level of craftsmanship and an exploration of light that all artists, to some degree, engaged with.

Similarly, Frederic Remington was contemporaneously forging an iconic vision of the American West, with dramatic narratives of cowboys, Native Americans, and cavalry. Joiner’s tranquil woodland scenes offer a stark contrast to Remington's dynamic and often violent frontier subjects, yet both artists contributed to the broader project of defining American identity through its diverse landscapes and experiences. Joiner’s contribution was a quieter, more introspective vision, rooted in the established beauty of the Eastern and Midwestern forests.

His participation in exhibitions, such as "The Artists of the Wonderland Way" held at the Carnegie Center, indicates his engagement with the regional art community and a desire to share his work with a broader public. The continued appearance of his paintings in auctions and their presence in museum collections like the McClung Museum (which received "Sunlight through Beeches" as a donation from the estate of Judge John W. and Ellen McClung Green) attest to his recognized skill and enduring appeal.

Technique and Presentation

Joiner's technical approach was grounded in traditional oil painting methods. He built up his compositions with careful attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of tree species and the textures of bark and foliage. His understanding of light was paramount; he knew how to use chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and dark) to create depth and drama. The way sunlight streams through branches, illuminates patches of the forest floor, or catches the edge of a leaf are hallmarks of his skill.

His color palette, while capable of capturing the fresh greens of spring, often leaned towards the rich, warm tones of autumn—russets, golds, deep browns, and oranges—or the cool, deep greens and blues of a shaded summer forest. These colors, combined with his mastery of light, created a strong sense of place and mood.

The distinctive shadow box frames were not mere afterthoughts but an integral part of his artistic presentation. These deep frames created a contained, almost theatrical space for the painting, enhancing the illusion of depth and making the illuminated areas within the canvas appear more vibrant. This framing choice suggests a conscious effort to control the viewer's experience and to heighten the atmospheric qualities of his work. It set his paintings apart and became a recognizable feature of his output.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Harvey Joiner's legacy lies in his dedicated and skillful portrayal of the American woodland. He was not an artist who sought out the grandiose or the exotic; instead, he found profound beauty in the familiar landscapes of Indiana and Kentucky. His work invites viewers to appreciate the subtle interplay of light, color, and texture that characterizes these sylvan environments.

In an era that saw the rise of modernism and avant-garde movements, Joiner remained committed to a representational style that emphasized atmosphere and natural beauty. His paintings offer a sense of peace and timelessness, a connection to the natural world that remains compelling. He captured a specific regional beauty with a universal appeal, demonstrating that profound artistic statements can be found in one's own backyard.

The continued interest in his work, as evidenced by auction sales and museum acquisitions, speaks to the enduring quality of his art. Collectors appreciate his technical skill, his distinctive handling of light, and the serene, evocative moods he created. Harvey Joiner may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his contemporaries, but he holds a secure place as a respected American landscape painter who masterfully captured the soul of the Midwestern and Southern forests. His paintings remain a testament to the quiet power of nature and the artist's ability to translate its ephemeral beauty onto canvas. His dedication to his chosen subject matter and his unique visual language ensure his continued relevance in the story of American art.