Helmi Ahlman Biese stands as a fascinating, if once overlooked, figure in the landscape of Finnish art. Active during a transformative period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, her life and work offer a compelling narrative of artistic dedication, the societal expectations placed upon women of her era, and the eventual, though sometimes delayed, recognition of talent. Her journey from an aspiring artist to a dedicated teacher, all while continuing to nurture her creative passion, paints a portrait of resilience. Biese's focus on the natural world, particularly the evocative landscapes of her Nordic homeland, places her within a significant tradition of painters who sought to capture the unique character and atmosphere of the North.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born Helmi Ahlman in 1867 in Finland, her early life was marked by an burgeoning interest in the arts. Encouragement came from her mother, Hilda Granstedt, who perhaps saw the spark of creativity in her daughter. However, the practicalities of life in the late 19th century often presented a stark contrast to artistic aspirations, especially for women. While the passion for art was present, her parents, likely concerned with her financial security and societal standing, viewed a full-time career as an artist as an unrealistic pursuit. This tension between personal artistic calling and familial or societal expectations would become a recurring theme in her life.

Despite these reservations, Helmi's desire to engage with art was strong. She embarked on her formal artistic training, a crucial step for any aspiring artist of the period. This initial foray into the structured world of art education would lay the foundation for her future endeavors, both as a painter and as an educator. The decision to pursue art, even with the caveat of a more "stable" career path, indicates a significant personal drive and a refusal to completely abandon her artistic inclinations.

Formal Artistic Education and a Teacher's Path

Helmi Ahlman's commitment to art led her to the Finnish Art Society's Drawing School in Helsinki, a significant institution for artistic training in Finland at the time. Here, she studied under notable instructors such as Carl Albert Juhani and Fredrik Stahls. This period would have been formative, exposing her to various techniques, artistic theories, and the camaraderie of fellow students. The curriculum would have likely focused on foundational skills in drawing and painting, essential for any artistic discipline.

Following her initial studies, Ahlman pursued a qualification that would provide her with a more secure profession. She attended Adolf Becker's private conservatory, which was affiliated with the Imperial Alexander Academy, to complete her art teacher's qualification. This was a practical step, aligning with her parents' concerns while still keeping her deeply involved in the world of art. Becoming a qualified drawing teacher opened a pathway for a respectable career, one that was considered more suitable for a woman than the often precarious life of a professional artist. This dual track – artist and teacher – would define much of her professional life.

Marriage, Teaching, and Continued Artistic Endeavors

In the late 1880s, Helmi Ahlman became engaged to Johan Hjalmar Biese, and they married in 1896. Upon marriage, she adopted her husband's surname, becoming known as Helmi Ahlman Biese, or often simply Helmi Biese. It is reported that her husband was supportive of her artistic pursuits. However, the demands of establishing a home and, more significantly, her career as a teacher, meant that her own artistic production often had to take a secondary role.

Biese embarked on a dedicated teaching career. She taught at the upper secondary school in Porvoo, a picturesque town known for its historic wooden houses, which may have offered some visual inspiration. Later, she taught at the Helsinki Women's School and, significantly, at the Helsinki Craft School (Taideteollisuuskeskuskoulu, a precursor to the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture). Her tenure at the Helsinki Craft School spanned from the mid-1900s to the mid-1920s, indicating a long and committed period as an educator, imparting artistic knowledge and skills to new generations. While teaching provided financial stability and a connection to the art world, it inevitably consumed time and energy that might otherwise have been devoted to her personal painting.

Despite the demands of her teaching career, Helmi Biese did not abandon her own art. She continued to paint, driven by her love for nature and perhaps a desire for personal expression that teaching alone could not fulfill. There were aspirations for travel abroad to broaden her artistic horizons, a common practice for artists seeking new influences and experiences. However, these plans, for various reasons, did not come to fruition, leaving her to draw inspiration primarily from her immediate surroundings and the Finnish landscape.

Exhibitions and Critical Reception

Helmi Biese did participate in the art world through exhibitions, though the reception was not always what an artist might hope for. In 1920, her works were shown at an art exhibition in Paris. While exhibiting in Paris, the epicenter of the art world, was a significant step, the response to her work was reportedly mediocre. This experience might have been disheartening, yet it did not entirely deter her.

Three years later, in 1923, Biese held a solo exhibition at the Helsinki Art Museum (Konsthallen). Unfortunately, this exhibition also met with a poor reception, with some critics even deeming it "meaningless." Such harsh criticism can be devastating for an artist, particularly one who is juggling a demanding teaching career with their personal creative practice. It reflects the often-subjective nature of art criticism and the prevailing tastes of the time, which may not have been aligned with Biese's particular style or thematic concerns.

Despite these setbacks, Biese's passion for depicting the natural world, especially the stark beauty of winter and the dynamic power of the sea, continued to fuel her work. These themes, often considered strong and even "masculine" in their execution, would later contribute to a re-evaluation of her artistic contributions.

Thematic Focus: The Nordic Landscape

Helmi Ahlman Biese's artistic output primarily centered on Nordic landscape painting. This genre was particularly potent in the Nordic countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as artists sought to define a sense of national identity and capture the unique light, atmosphere, and topography of their homelands. Biese's work fits within this tradition, focusing on the Finnish environment.

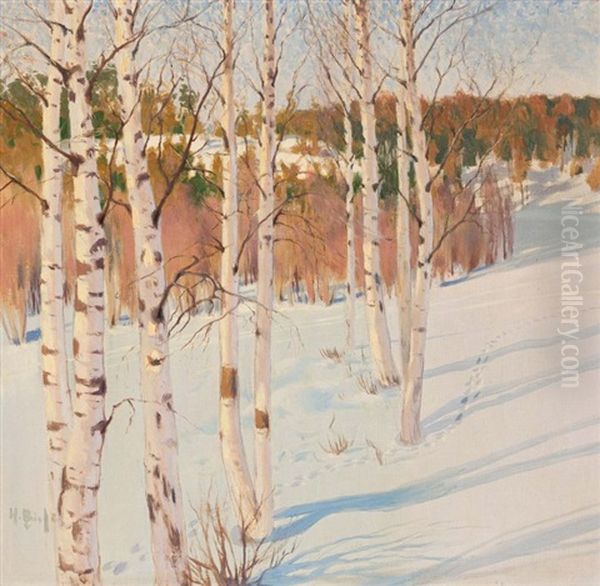

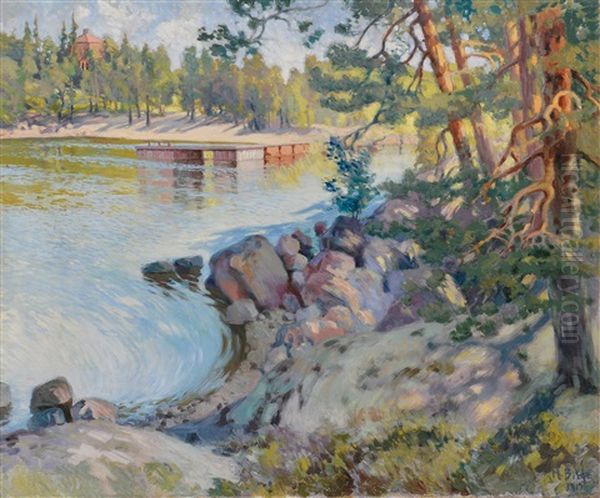

Her paintings often depicted winter scenes, capturing the subtle hues of snow and ice, the stark silhouettes of trees against a cold sky, and the quiet solitude of the frozen land. Marine landscapes were another significant theme, reflecting Finland's extensive coastline and archipelago. These subjects allowed for an exploration of nature's raw power and its more tranquil moments. Her style was described by some later commentators as possessing a "masculine" quality, likely referring to a boldness in composition, strong brushwork, or an unsentimental approach to her subjects. This characterization is interesting, especially when considering the societal expectations for female artists, who were often steered towards more "delicate" or domestic themes.

The comparison of her work to that of other Finnish artists like Fanny Churberg (1845-1892), known for her dramatic and expressive landscapes, and Väinö Blomstedt (1871-1947), a notable symbolist and landscape painter, suggests that Biese was engaging with similar artistic concerns and achieving a comparable level of expressive power, even if contemporary recognition was limited.

"An Old Pine": A Rediscovered Testament

One of Helmi Ahlman Biese's most significant known works is the painting titled "An Old Pine" ("Vanha mänty"), created in 1921. This painting embodies her dedication to capturing the essence of the Finnish landscape. The lone, resilient pine tree is a powerful symbol in Nordic art and culture, often representing strength, endurance, and a connection to the ancient wilderness.

The history of "An Old Pine" is itself a compelling story. In 1931, Biese donated the painting to the Helsinki Craft School, where she had taught for many years. This act suggests a desire for her work to remain within an educational and artistic environment. For decades, the painting's whereabouts were somewhat obscure, a common fate for works by artists who do not achieve widespread fame during their lifetime.

Remarkably, in 2015, "An Old Pine" was rediscovered in a basement storage area of the University of Helsinki. This discovery brought renewed attention to Helmi Ahlman Biese and her work. The painting, now part of the Helsinki University Museum's collections, serves as a tangible link to her artistic vision and a testament to her skill. Its rediscovery has been instrumental in prompting a re-evaluation of her place in Finnish art history. The painting itself, with its depiction of a solitary, weathered tree, can be seen as a metaphor for the artist herself – resilient, rooted in her environment, and enduring despite periods of obscurity.

The Broader Context: Nordic Landscape Painting and Contemporaries

Helmi Ahlman Biese was working during a vibrant period for landscape painting across the Nordic countries and internationally. Her focus on the natural world connected her to a broader artistic current. Understanding her work benefits from considering the artistic milieu of her time, which included numerous painters dedicated to landscape.

Among her Finnish contemporaries who also explored landscape themes were giants like Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931), renowned for his depictions of Finnish nature and scenes from the national epic, the Kalevala. Other Finnish artists like Pekka Halonen (1865-1933), known for his serene winter landscapes, and Eero Järnefelt (1863-1937), who painted realistic portrayals of Finnish people and nature, were shaping the national artistic identity.

Beyond Finland, the Nordic region boasted many prominent landscape painters. In Sweden, Prince Eugen (1865-1947), a royal and a respected artist, created atmospheric and often melancholic landscapes. Anna Boberg (1864-1935), another Swedish artist, was particularly known for her powerful depictions of the Arctic landscapes of Lofoten. Gustaf Fjaestad (1868-1948), also Swedish, gained fame for his distinctive impasto technique in rendering snow-covered forests and frozen waters.

In Norway, Edvard Munch (1863-1944), though famed for his expressionistic portrayals of human emotion, also produced deeply evocative landscapes that often mirrored his psychological states. Harald Sohlberg (1869-1935) created iconic, almost mystical, depictions of Norwegian nature, such as his famous "Winter Night in the Mountains."

Further afield, but sharing a similar reverence for the untamed landscape, were artists like the Canadian painters who would form the Group of Seven. Figures such as Tom Thomson (1877-1917), whose vibrant depictions of the Canadian wilderness were highly influential, and Lawren S. Harris (1885-1970) with his stylized and spiritual interpretations of northern landscapes, and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873-1932), who captured the rugged beauty of Algoma and the Rockies, were part of a similar movement to define national identity through landscape. Even an artist like Emily Carr (1871-1945) from Canada's West Coast, with her focus on the forests and Indigenous cultures of British Columbia, shared this deep engagement with the spirit of place.

The Russian painter Ivan Shishkin (1832-1898), though from an earlier generation, was a master of forest landscapes, whose detailed realism set a high bar for depicting sylvan scenes. And while stylistically very different, the pioneering abstract artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) from Sweden also began her career with more conventional landscape and portrait work before embarking on her groundbreaking spiritual abstractions.

While there is no specific record of direct collaboration or intense competition between Helmi Biese and many of these international figures, their collective work demonstrates a widespread artistic engagement with landscape during this period. They were all, in their own ways, responding to the natural world, exploring its beauty, its power, and its symbolic resonance. Biese's contribution to Finnish landscape painting is part of this larger, international conversation about nature and art.

Later Recognition and Enduring Legacy

Helmi Ahlman Biese passed away in 1933. During her lifetime, she may not have achieved the widespread fame or critical acclaim of some of her contemporaries. Her dual role as a dedicated teacher likely limited the time and energy she could devote to promoting her own artistic career. The art world, then as now, could be fickle, and critical tastes did not always align with her particular vision.

However, the narrative of art history is one of constant re-evaluation. Artists who were overlooked in their own time can find new appreciation with later generations. For Helmi Biese, this process seems to have begun towards the end of the 20th century and gained momentum in the 21st, particularly spurred by the rediscovery of "An Old Pine." Art historians and critics began to look anew at her work, recognizing its strength, sincerity, and its valuable contribution to the tradition of Finnish landscape painting.

The mention of her work being exhibited in 1950 at the Helsinki Art Museum, some 17 years after her death, suggests an early posthumous acknowledgment of her talent, perhaps as part of a group show or a retrospective look at Finnish art of her period. Such events are crucial for keeping an artist's legacy alive and introducing their work to new audiences.

Her story is a reminder that artistic significance is not always measured by contemporary fame. The dedication to her craft, her perseverance in the face of lukewarm critical reception, and her commitment to both creating and teaching art speak to a profound engagement with the artistic spirit. The "masculine" strength attributed to her landscape paintings, combined with her focus on the quintessential Finnish themes of winter and sea, positions her as an important, if nuanced, voice in her nation's art.

Conclusion: An Artist of Quiet Strength

Helmi Ahlman Biese's life (1867-1933) offers a window into the world of a female artist in Finland at the turn of the 20th century. She navigated the expectations of her family and society by pursuing a teaching career, yet she never relinquished her personal passion for painting. Her landscapes, particularly those capturing the stark beauty of the Finnish winter and the power of the sea, reveal a keen observational eye and a strong expressive capability.

While contemporary critical acclaim may have been modest, and her artistic output perhaps constrained by her teaching responsibilities, her work has found increasing recognition in recent times. The rediscovery of "An Old Pine" served as a catalyst for this renewed interest, allowing a modern audience to appreciate her contribution to the rich tradition of Nordic landscape painting. Helmi Ahlman Biese's legacy is one of quiet strength, artistic integrity, and a deep connection to the natural world of her homeland, securing her a deserved place in the annals of Finnish art history. Her journey underscores the importance of looking beyond the most celebrated names to uncover the diverse talents that have shaped our artistic heritage.