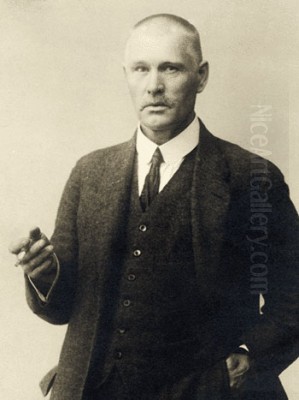

Pekka Halonen (1865-1933) stands as one of the most beloved and significant figures in Finnish art history, a central painter during the nation's "Golden Age" of art at the turn of the 20th century. Renowned primarily for his evocative landscapes, particularly his masterful depictions of Finnish winter, Halonen captured the essence of his homeland's nature and the spirit of its people with a style rooted in Realism yet touched by contemporary European currents and a deep national sentiment. His work continues to resonate, offering a window into a pivotal period of Finnish cultural identity formation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Pekka Halonen was born on September 23, 1865, in Linnasalmi, Lapinlahti, within the Savo region of Eastern Finland. He hailed from a farming family, a background that instilled in him a lifelong connection to the land and the rhythms of rural life. His father, Olli Halonen, was a farmer and craftsman, while his mother, Vilhelmiina (Miina) Uotinen, was known for her talent as a folk musician, particularly playing the kantele, a traditional Finnish stringed instrument. This artistic inclination in the family undoubtedly influenced young Pekka, who also learned to play the kantele and retained a love for music throughout his life.

Despite the practical demands of farm life and an initial, brief exploration into training as a primary school teacher, Halonen's true calling lay in the visual arts. His interest was strong enough that in 1886 (though some sources mention 1875 for an earlier move, his formal studies began later), he moved to Helsinki to pursue artistic training seriously. He enrolled in the Art Society's Drawing School (now part of the Academy of Fine Arts), where he studied diligently for four years, laying the technical foundation for his future career. His teachers included influential figures in Finnish art, such as Carl Eneas Sjöstrand and Adolf von Becker.

Parisian Studies and Developing Style

Like many ambitious artists of his generation seeking exposure to the latest international trends, Halonen traveled to Paris in 1890. This period was crucial for his artistic development. He studied at the Académie Julian, a popular private art school that attracted students from around the world. Perhaps more significantly, he also spent time studying at the Académie Colarossi and received guidance from Paul Gauguin in 1894. Gauguin's influence, particularly his emphasis on synthetism – simplifying forms and using bold color for expressive effect – left a mark on Halonen, although Halonen would adapt these ideas to his own temperament and subject matter.

During his time in Paris and subsequent trips abroad, including Italy in 1896-97, Halonen absorbed various influences. French Impressionism, with its focus on light and atmosphere, certainly informed his approach to landscape painting. He became adept at capturing fleeting moments and the subtle effects of light on snow, water, and foliage. However, Halonen never fully embraced the broken brushwork or dissolved forms characteristic of core Impressionism. His work retained a strong grounding in realistic observation, influenced perhaps by the Naturalism of painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage.

He was also receptive to Symbolism, a movement prevalent in Paris that sought to convey ideas and emotions through suggestive imagery rather than direct representation. While Halonen remained primarily a landscape and genre painter, a certain symbolic weight and moodiness can be felt in many of his works, particularly those depicting the vast, silent Finnish wilderness. Furthermore, like many artists of the era, Halonen was influenced by Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art, particularly woodblock prints. This can be seen in some of his compositions, with their flattened perspectives, decorative arrangements of forms, and attention to line.

National Romanticism and the Finnish Landscape

Returning to Finland, Halonen integrated these international influences into a distinctly Finnish context. He became a key exponent of National Romanticism, an artistic and cultural movement that swept through Finland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During a period when Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russian rule, this movement sought to define and celebrate a unique Finnish identity through art, music, literature, and architecture, often drawing inspiration from Finnish folklore, mythology (especially the national epic, the Kalevala), and the pristine natural landscape.

Halonen's contribution to National Romanticism lay primarily in his profound connection to and depiction of the Finnish landscape. He saw the forests, lakes, and snow-covered vistas not just as picturesque scenes but as embodiments of the Finnish spirit – resilient, serene, and deeply connected to nature. He traveled extensively throughout Finland, particularly in Karelia and his native Savo, seeking authentic landscapes and capturing the specific character of different regions.

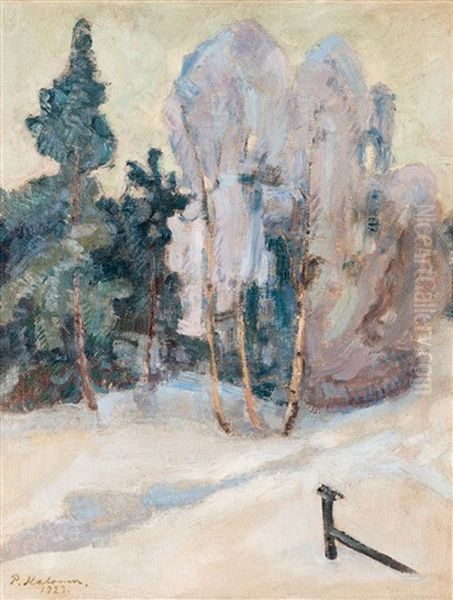

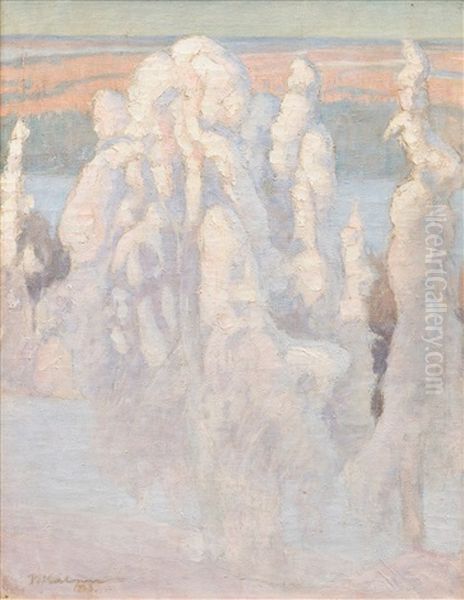

Winter became a signature theme for Halonen. He possessed an extraordinary ability to render the nuances of snow and ice under different light conditions – the crisp blue shadows of a sunny day, the soft grey light of an overcast sky, the glistening surface of frozen lakes. His winter scenes convey both the harshness and the sublime beauty of the Nordic climate, often imbued with a sense of quiet solitude and introspection. Works like Winter Day (1895) and later masterpieces showcase this sensitivity.

Halosenniemi: A Home and Artists' Haven

In 1895, Pekka Halonen married Maija Mäkinen, a music student. Their partnership was strong, and Maija became a supportive presence throughout his life. In 1899, seeking a permanent home and studio space away from the bustle of Helsinki but close enough to maintain connections, the Halonens settled on the shores of Lake Tuusula (Tuusulanjärvi). This area was rapidly becoming a vibrant artists' colony, attracting writers, painters, and composers drawn to its scenic beauty and the spirit of creative community.

Here, Pekka Halonen designed and oversaw the construction of their remarkable log home and studio, completed in 1902, which they named "Halosenniemi" (Halonen's Cape). The building itself is a significant example of National Romantic architecture. Constructed from massive pine logs in the traditional Finnish style, it also incorporates elements inspired by English country houses and Art Nouveau aesthetics. The large studio window facing north provided ideal light for painting, and the house was designed to harmonize with its natural surroundings on the wooded peninsula.

Halosenniemi quickly became more than just a family home; it was a central hub for the Lake Tuusula artist community. The Halonens hosted frequent gatherings, bringing together leading cultural figures. Regular visitors included the composer Jean Sibelius, the writer Juhani Aho (who lived nearby at Ahola with his wife, the painter Venny Soldan-Brofeldt), the poet Eino Leino, and fellow painters like Eero Järnefelt and, importantly, Halonen's close friend Akseli Gallen-Kallela. These gatherings fostered lively discussions about art, music, literature, and the future of Finnish culture.

Artistic Themes and Mature Style

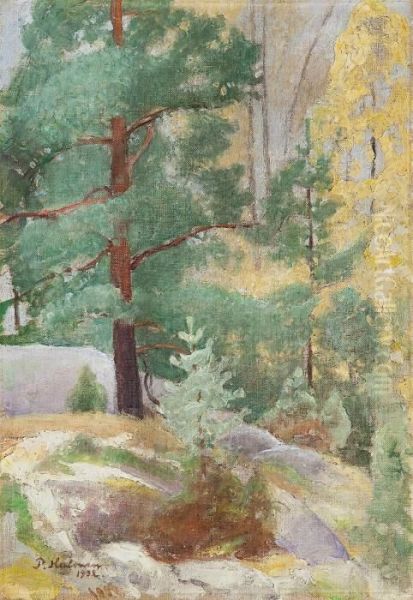

Throughout his mature career, based at Halosenniemi, Halonen continued to explore his core themes with increasing depth and refinement. His style solidified into a form of lyrical realism, characterized by careful observation, solid draftsmanship, and a sensitive use of color and light to evoke mood and atmosphere.

Winter Landscapes: This remained his most celebrated subject. He painted snow not just as white but captured its myriad blues, violets, pinks, and yellows reflecting the sky and surrounding environment. He depicted the weight of snow on branches, the patterns of frost, and the stark beauty of the frozen world. Winter Forest (1915), dedicated to Sibelius, is a prime example of his ability to convey the silent majesty of the snow-laden woods.

Forests and Water: Halonen had a deep affinity for the Finnish forest. He painted towering pines, dense spruce stands, and delicate birch trees, often focusing on the interplay of light filtering through the canopy or reflecting off water surfaces. His depictions of Lake Tuusula and other lakes capture their changing moods, from calm reflections to wind-rippled surfaces. Forest Edge by the Shore (1929) shows his continued engagement with these motifs late in his career.

Rural Life and Labor: Drawing on his own background, Halonen often depicted scenes of everyday rural life and traditional work. Unlike some contemporaries who might romanticize or dramatize peasant life, Halonen approached these subjects with quiet dignity and respect. Road Builders in Karelia (also known as Pioneers in Karelia, 1900) is a powerful example, showing men engaged in the arduous task of clearing land, symbolizing the effort involved in building the nation. Mowers (1891) is an earlier work exploring similar themes.

The Kalevala: Like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Halonen was inspired by the Kalevala. While Gallen-Kallela is perhaps more famous for his dramatic mythological scenes, Halonen also created illustrations and paintings based on the epic, often focusing on the relationship between the characters and the natural world described in the poems. His interpretations tended to be more lyrical and grounded than Gallen-Kallela's.

Portraits and Figures: Although primarily a landscape painter, Halonen was also a capable portraitist. His portraits, often of family members or friends, are characterized by their psychological insight and unpretentious realism. Double Portrait (1895), depicting himself and his wife Maija, is a tender and intimate work. His earlier Italian Girl (1893-94) reflects his academic training and travels.

Artistic Philosophy: Halonen believed that art should bring inner peace and harmony, stating, "Art should not jar the nerves like sandpaper – it should produce a feeling of peace." He painted primarily for himself, driven by his personal response to the world around him rather than by commissions or market demands. This sincerity and deep connection to his subjects are palpable in his work.

Key Representative Works

While Halonen produced a large body of work, several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his style and themes:

The Wilderness (Wildmark / Erämaa) (1899): Often considered one of his early masterpieces, this painting depicts a vast, snow-covered wilderness landscape, possibly inspired by Karelia. It conveys a powerful sense of solitude, the raw beauty of nature, and the spirit of the Finnish frontier. The handling of light on the snow is exemplary.

Road Builders in Karelia (Tienraivaajia Karjalassa / Pioneers in Karelia) (1900): A significant work depicting Finnish perseverance and the connection between human labor and the land. The figures are integrated into the landscape, emphasizing their struggle against and harmony with nature. It reflects the national spirit of building a future.

Winter Forest (Talvinen metsä) (1915): Dedicated to his friend Jean Sibelius, this painting captures the profound silence and beauty of a snow-laden Finnish forest. The intricate rendering of snow on the branches and the subtle cool colors create a deeply atmospheric and almost musical quality.

Sauna in the Snow (Sauna lumessa) (various versions, e.g., 1908): This theme, depicting a traditional Finnish log sauna nestled in a snowy landscape, often with smoke rising from the chimney, captures a quintessential aspect of Finnish culture and the contrast between the warmth inside and the cold outside. It evokes feelings of coziness, tradition, and resilience.

Boy Playing on the Shore (Rannalla leikkivä poika) (1895): An example of his figure painting within a landscape, showing sensitivity to childhood and the natural environment.

Double Portrait (Kaksoismuotokuva) (1895): An intimate portrayal of the artist and his wife, showcasing his skill in portraiture and capturing personal relationships.

Forest Edge by the Shore (Rantametsää) (1929): A later work demonstrating his enduring fascination with the interplay of trees, water, and light, painted with a mature and confident hand.

Connections and Contemporaries

Pekka Halonen was deeply embedded in the artistic life of his time, maintaining significant relationships with many key figures of the Finnish Golden Age and beyond.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931): Perhaps Halonen's closest artistic peer and friend. Born in the same year, they shared a deep interest in Finnish nature and the Kalevala. While Gallen-Kallela's style was often more dramatic and symbolist, they mutually respected and influenced each other. They were both central figures in shaping a national Finnish art. Their discussions at Halosenniemi and elsewhere were vital exchanges.

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957): The preeminent Finnish composer was a close friend and neighbor at Lake Tuusula. Sibelius often visited Halosenniemi, and the shared appreciation for Finnish nature undoubtedly resonated between the painter and the composer. Halonen's dedication of Winter Forest to Sibelius underscores this connection.

Eero Järnefelt (1863-1937): Another prominent Golden Age painter and neighbor at Lake Tuusula, known for his realistic portraits and landscapes, particularly scenes from Koli National Park. Järnefelt shared Halonen's commitment to depicting Finnish nature and people authentically.

Juhani Aho (1861-1921) & Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (1863-1945): The writer Aho and his wife, the painter Soldan-Brofeldt, were core members of the Tuusula community and close friends of the Halonens. Their proximity fostered a rich interdisciplinary cultural environment.

Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905): A slightly older, highly influential Finnish painter whose realist and impressionist works paved the way for the Golden Age generation. Halonen would have certainly known and respected Edelfelt's work and status.

Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946): A highly individualistic painter who moved towards modernism, Schjerfbeck was a contemporary, though her artistic path diverged significantly from Halonen's realism.

Magnus Enckell (1870-1925) & Hugo Simberg (1873-1917): Leading figures of Finnish Symbolism. While Halonen's style differed, he operated within the same cultural milieu where Symbolist ideas were influential. Simberg, known for his unique and often macabre imagery, represents another facet of the era's artistic diversity.

Väinö Blomstedt (1871-1947) & Ellen Thesleff (1869-1954): Contemporaries who explored Synthetism, Symbolism (Blomstedt), and expressive colorism (Thesleff), showcasing the range of styles developing alongside Halonen's realism.

Juho Rissanen (1873-1950): Known for his powerful, often stark depictions of Finnish peasant life, Rissanen shared Halonen's interest in portraying the common people, albeit often with a different stylistic emphasis.

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903): The French Post-Impressionist master provided direct guidance during Halonen's time in Paris, influencing his approach to form and color, even if Halonen adapted these lessons significantly.

Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898): The leading French Symbolist muralist whose work was widely admired in Paris; his emphasis on mood and simplified forms likely resonated with Halonen and other artists exploring Symbolist ideas.

John Duncan (1866-1945): A Scottish Celtic Revival painter whose work, focusing on myth and landscape, shares some thematic parallels with the National Romantic interests of Halonen and his Finnish contemporaries, highlighting broader European trends in cultural revival through art.

Halonen's engagement with these artists, both Finnish and international, through study, friendship, and shared cultural projects, enriched his work and solidified his position within the artistic landscape of his time. The Tuusula Lake community, fostered by individuals like Halonen, Sibelius, Järnefelt, and Aho, remains a unique example of concentrated creative energy in Finnish cultural history.

Legacy and Recognition

Pekka Halonen continued to paint actively until his death in Tuusula on December 1, 1933. Throughout his career, he gained widespread respect and recognition in Finland. His works were exhibited regularly and acquired by major collections. Today, his paintings are prominently featured in the Finnish National Gallery (Ateneum Art Museum) in Helsinki and other significant Finnish museums.

His home, Halosenniemi, was preserved and eventually opened to the public as a museum in 1949. It stands today as a beautifully maintained house museum, showcasing Halonen's art, his studio, the family's living quarters, and offering insights into the life of the artist and the Lake Tuusula community. It remains a popular destination, allowing visitors to step into the environment where much of his iconic work was created.

Pekka Halonen's legacy extends beyond his individual paintings. He played a crucial role in defining a visual identity for Finland during a critical period of national awakening. His depictions of the Finnish landscape, particularly the winter scenes, have become deeply ingrained in the national consciousness, symbolizing the beauty, resilience, and unique character of the country. He demonstrated how international artistic trends could be synthesized with local traditions and personal vision to create art that is both universally appealing and profoundly national. His commitment to his craft, his deep love for his homeland's nature, and his quiet, sincere artistic voice ensure his enduring importance in the history of Finnish art.

Conclusion

Pekka Halonen remains a cornerstone of Finnish art. As a leading figure of the Golden Age and a master of National Romantic landscape painting, he translated the Finnish experience – its nature, its people, its seasons – into a visual language that was both authentic and artistically sophisticated. Influenced by European currents but firmly rooted in his native soil, he created works that celebrate the quiet dignity of rural life and the sublime beauty of the Finnish wilderness, especially its iconic winter. Through his art and his central role in the Lake Tuusula artists' colony, Halonen made an indelible contribution to Finland's cultural heritage, leaving behind a body of work that continues to inspire and resonate with audiences today. His paintings are more than just depictions; they are felt experiences of the Finnish soul.