Hendrick de Clerck stands as a significant, albeit often overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Flemish art during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Active primarily in Brussels, his lifespan (circa 1560 – 1630) placed him squarely at a pivotal moment of artistic transition, bridging the elegant, sophisticated style of Late Mannerism with the burgeoning dynamism and emotional intensity of the Baroque. While his name may not resonate as loudly as his illustrious contemporary, Peter Paul Rubens, De Clerck was a highly accomplished painter who enjoyed prestigious patronage, particularly from Archduke Albert VII of Austria and his wife, Isabella Clara Eugenia, the governors of the Spanish Netherlands. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant colour, and often complex compositions, offers invaluable insights into the courtly life, religious fervor, and political currents of his time.

Origins and Artistic Formation

Pinpointing Hendrick de Clerck's exact origins remains somewhat challenging for art historians. While he is firmly associated with Brussels, where he spent the majority of his productive career, sources suggest he may have been born in the broader region of Flanders, possibly within the territory of the present-day Netherlands, around the year 1560. Regardless of his precise birthplace, Brussels became the center of his world, the city where he would establish his reputation and serve the highest echelons of society.

His artistic training is another area where definitive proof is elusive, yet tradition holds that he may have been a pupil of the influential Antwerp painter Marten de Vos (c. 1532–1603). De Vos was a leading figure in Antwerp Mannerism, known for his large-scale religious and allegorical compositions, heavily influenced by his own studies in Italy, particularly Venice. If De Clerck did study under De Vos, he would have absorbed the tenets of Mannerism – elongated figures, graceful S-curve poses, intricate compositions, and a sophisticated, often artificial, elegance. However, this apprenticeship is not universally accepted, and De Clerck's distinct style, particularly his later evolution, suggests other influences were also at play. Unlike De Vos, whose career was centered in the bustling commercial hub of Antwerp, De Clerck gravitated towards the administrative and courtly center of Brussels.

The Italian Sojourn: A Formative Experience

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his generation, De Clerck is believed to have undertaken a journey to Italy, likely sometime in the 1580s or early 1590s. This period of study and travel south was considered almost essential for artists seeking to master the principles of classical art and the innovations of the Italian Renaissance and burgeoning Baroque. Evidence suggests he spent time in key artistic centers, most notably Rome and possibly Florence. Exposure to the masterpieces of Michelangelo, Raphael, and contemporary Italian painters would have profoundly impacted his artistic vision.

Art historical analysis, particularly of works attributed to his Italian period or created shortly after his return, reveals distinct stylistic shifts. These paintings often exhibit a newfound grandeur, brighter and more vibrant colour palettes, and a particularly meticulous rendering of rich fabrics and complex drapery folds. This heightened attention to texture and colour, combined with a certain monumentality, echoes the work of some Italian contemporaries. The painting St. John in a Landscape, for instance, has been cited by scholars as potentially reflecting the deep impression his Italian experiences made upon him. Indeed, some works from this period were initially misattributed until later research confirmed De Clerck's authorship, highlighting how effectively he absorbed and adapted Italianate styles. The exact reasons for his return north are unclear, but the turbulent political and religious climate across Europe, including the ongoing conflicts involving the Habsburg domains, may have played a role. His Italian experience, however, undoubtedly enriched his artistic vocabulary, providing a foundation upon which he would build his mature style back in Brussels. Other Flemish artists like Otto van Veen (Rubens's teacher) and the internationally active Bartholomeus Spranger also benefited immensely from their time in Italy.

Court Painter to Albert and Isabella

Upon his return to the Low Countries, Hendrick de Clerck established himself in Brussels and soon attracted the attention of the highest patrons in the land: Archduke Albert VII of Austria and his wife, the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain. Appointed as governors of the Spanish Netherlands in 1598, Albert and Isabella presided over a court in Brussels that aimed to restore stability, promote the Catholic faith following the upheavals of the Reformation, and project an image of legitimate Habsburg authority. Art played a crucial role in this agenda, and De Clerck became one of their favoured court painters.

His service to the Archdukes, documented from at least 1594 onwards, involved creating works that fulfilled various functions. He produced numerous religious altarpieces for churches under their patronage, reinforcing Counter-Reformation doctrine and piety. Equally important were the mythological, allegorical, and historical paintings commissioned for the court itself. These works often carried subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) political messages, functioning as sophisticated propaganda. For example, De Clerck is known to have depicted Archduke Albert in the guise of the sun god Apollo, a symbol of enlightenment, order, and rightful rule, while Isabella was sometimes portrayed with attributes evoking the purity and virtue of the Virgin Mary. This use of allegory and symbolism was a common feature of court art throughout Europe, designed to flatter the rulers and legitimize their power. While Peter Paul Rubens, also patronized by Albert and Isabella, operated on a grander, more international scale, often undertaking diplomatic missions alongside his artistic ones, De Clerck provided a steady stream of high-quality paintings tailored specifically to the needs and tastes of the Brussels court.

Navigating Styles: Mannerism's Elegance and Baroque's Dynamism

Hendrick de Clerck's artistic style occupies a fascinating position between two major artistic movements. His formative years were steeped in the prevailing Late Mannerism of the Southern Netherlands. This is evident in the elegant, often elongated proportions of his figures, their graceful, sometimes artificially complex poses (figura serpentinata), and the decorative quality apparent in many of his compositions. The intricate details, rich costumes, and sophisticated arrangements recall the courtly aesthetics associated with international Mannerism, seen in the work of artists like Bartholomeus Spranger, though De Clerck's interpretation was generally less extravagant.

However, De Clerck did not remain static. His work increasingly absorbed elements of the emerging Baroque style, which was gaining momentum across Europe, particularly in Catholic regions, championed by artists like Caravaggio in Rome and, soon after, Rubens in Antwerp. From the Baroque, De Clerck adopted a richer, more vibrant colour palette, moving away from the sometimes acidic or cooler tones of Mannerism towards warmer, more saturated hues. He demonstrated a growing interest in dramatic effects of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), using contrasts to model forms and enhance the emotional impact of his scenes, although generally less intensely than Caravaggio or Rembrandt. While retaining a Mannerist sense of refinement, his figures often gained a greater sense of volume and naturalism, and his religious works, in particular, conveyed the heightened emotionalism and didactic clarity favoured by the Counter-Reformation. He was also adept at producing smaller "cabinet paintings," meticulously finished works intended for private collectors and connoisseurs, showcasing his technical skill on an intimate scale.

Masterpieces and Signature Themes

De Clerck's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects popular during his time, with religious narratives and mythological or allegorical scenes being particularly prominent. His interpretations reveal both his technical mastery and his engagement with the cultural and religious context of the Counter-Reformation Southern Netherlands.

Religious Narratives: De Clerck was frequently commissioned to paint altarpieces and devotional images. Works like Moses Striking the Rock exemplify his approach to Old Testament themes. Such subjects, depicting miracles and divine intervention, were popular Counter-Reformation choices, emphasizing God's power and the importance of faith and leadership. De Clerck renders the scene with clarity, focusing on the central miracle while populating the canvas with numerous figures whose reactions convey the drama of the event. Another biblical subject he treated was Susanna and the Elders, a story that allowed artists to explore themes of virtue, voyeurism, and divine justice, often featuring intricate compositions and rich details.

His depiction of Paradise showcases his ability to handle large, multi-figure compositions with a sense of divine order and harmony. Typically centered around the figure of the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven, surrounded by choirs of angels and ranks of saints, such works employed a rich colour scheme, often balancing warm and cool tones to create a luminous, otherworldly atmosphere. These paintings served as powerful visual statements of Catholic doctrine and devotional practice.

Mythology and Allegory: As a court painter, De Clerck frequently turned to classical mythology and allegory, subjects that resonated with the educated elite and provided ample opportunity for symbolic representation. Abundance and the Four Elements is a prime example, likely an allegory celebrating the peace and prosperity hoped for under the rule of Albert and Isabella. The painting skillfully blends figures representing abstract concepts (Abundance, Earth, Air, Fire, Water) into a harmonious composition, showcasing De Clerck's command of perspective, detailed rendering of textures (fruits, fabrics, flesh), and sophisticated use of light and colour. It reflects a transition, combining Mannerist grace with a more Baroque sense of fullness and vibrancy.

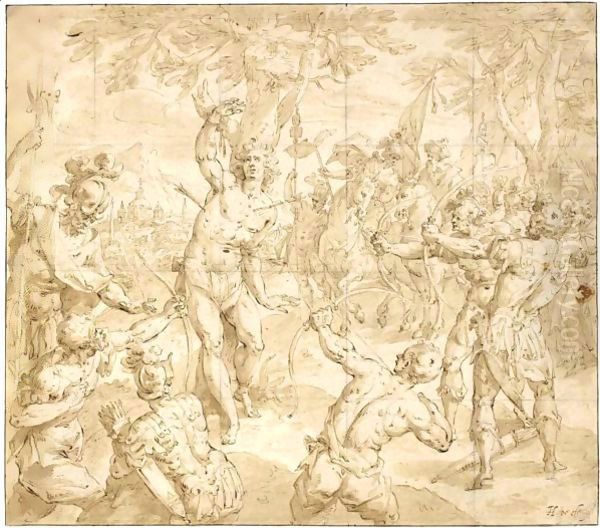

Other mythological works, such as The Contest between Apollo and Pan, The Feast of Achelous, and Mount Parnassus, further demonstrate his engagement with classical themes favoured by the court. Apollo and Pan depicts the musical contest judged by King Midas, a story about judgment and the hierarchy of art forms. The Feast of Achelous portrays the river god hosting Theseus, offering a chance to depict a lively banquet scene with numerous figures and rich still-life elements. Mount Parnassus, the mythical home of Apollo and the Muses, allowed for an idealized depiction of artistic inspiration and harmony. In all these works, De Clerck employed balanced compositions, often complex groupings of figures, and a characteristically bright palette, aligning with the decorative and intellectual tastes of his patrons.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

The practice of collaboration between specialist painters was common in the Southern Netherlands during this period, allowing artists to combine their respective strengths for optimal results. Hendrick de Clerck participated in this tradition, most notably through his collaborations with the Brussels-based landscape painter Denis van Alsloot (c. 1570–1626/28). Van Alsloot was renowned for his detailed forest scenes and topographical views, often featuring courtly processions or festivities. In their joint works, Van Alsloot typically painted the landscape setting, while De Clerck added the figures, bringing mythological or biblical narratives to life within Alsloot's meticulously rendered environments. Some of these collaborative pieces bear the signatures of both artists, attesting to their partnership. This practice mirrored other famous collaborations, such as those between Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, where Rubens might paint the figures and Brueghel the exquisite floral or landscape details.

De Clerck's relationship with Peter Paul Rubens remains a key point of comparison. They were contemporaries, both highly skilled, and both served the Archdukes Albert and Isabella. However, their artistic trajectories and ultimate legacies diverged significantly. Rubens, returning from Italy in 1608, rapidly became the dominant force in Flemish painting, revolutionizing the art scene with his dynamic compositions, dramatic energy, and painterly bravura. While some early sources suggest De Clerck's established style might have initially influenced the younger Rubens upon his return, Rubens quickly surpassed him in innovation and international fame. De Clerck continued to be highly regarded, particularly within the Brussels court, but his style, while accomplished, was perceived as more conservative and less groundbreaking than Rubens's dynamic Baroque. He faced criticism, particularly later in his career, for sometimes repeating compositions or figure types, lacking the seemingly inexhaustible invention of Rubens.

Beyond Rubens and Van Alsloot, De Clerck operated within a vibrant artistic milieu. Other significant Flemish painters of the era included Abraham Janssens, an important early Baroque painter in Antwerp and a rival to Rubens; Jacob Jordaens and Anthony van Dyck, both younger artists who emerged from Rubens's circle to become major masters in their own right; the prolific Francken dynasty, particularly Frans Francken the Younger, known for detailed cabinet paintings; and landscape specialists like Joos de Momper II. De Clerck's work should be understood within this context of intense artistic activity, competition, and collaboration.

Later Years and Art Historical Assessment

Hendrick de Clerck remained active in Brussels throughout the first three decades of the seventeenth century, continuing to produce works for the court, churches, and private patrons until his death in 1630. While he maintained a high level of technical skill, art historical consensus suggests his later work sometimes showed signs of conservatism, adhering to established formulas rather than embracing the full dynamism of the High Baroque as exemplified by Rubens and his followers. The criticism regarding the repetition of motifs and compositions pertains mainly to this later period, perhaps indicating a busy workshop fulfilling commissions efficiently, but potentially at the expense of fresh invention.

Despite being overshadowed by the towering figure of Rubens, Hendrick de Clerck's contribution to Flemish art history is undeniable. He was a leading master in Brussels for several decades, playing a crucial role as a court painter during the important reign of Albert and Isabella. His work expertly navigated the transition from the sophisticated elegance of Late Mannerism to the colour and emotionalism of the early Baroque. He was a key exponent of Counter-Reformation art in the Spanish Netherlands, creating compelling religious imagery that served the spiritual and political aims of his patrons. His mythological and allegorical paintings provide valuable documentation of courtly taste and Habsburg propaganda.

In conclusion, Hendrick de Clerck was a highly skilled and historically significant painter. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Rubens, he was a master craftsman whose works embody the artistic complexities of his time. His paintings, characterized by their careful execution, vibrant colour, and blend of Mannerist grace and Baroque sensibility, offer a distinct and valuable perspective on the art of the Southern Netherlands at the turn of the seventeenth century. He remains an important figure for understanding the artistic patronage of the Archdukes and the broader cultural landscape of Brussels during a pivotal era in European art history.