Hans Rottenhammer the Elder stands as a pivotal figure in German art at the turn of the 17th century. Born in Munich in 1564 and passing away in Augsburg in 1625, his career charts a fascinating course from the late Mannerist traditions of his homeland to the vibrant artistic centres of Italy, particularly Venice and Rome. He became renowned for his highly finished cabinet paintings, often executed on copper, and his fruitful collaborations with prominent landscape specialists. Rottenhammer successfully synthesized Northern precision with Italianate elegance, creating a style that found favour with discerning collectors and patrons across Europe, including Emperor Rudolf II. His life and work illuminate the dynamic cultural exchange between Northern Europe and Italy during this era. While most historical sources confirm his lifespan as 1564 to 1625, it is worth noting that minor discrepancies exist in some records, though the 1625 date of death is widely accepted by art historians.

Early Life and Training in Munich

Hans Rottenhammer entered the world in Munich, the capital of the Duchy of Bavaria, in 1564. His background was respectable; his father, Thomas Rottenhammer, held the position of a court stable master, suggesting a connection, albeit perhaps indirect, to the ducal court environment. This context might have provided the young Rottenhammer with some exposure to the arts and the world of patronage from an early age. The artistic scene in Munich during the late 16th century was influenced by both local traditions and increasing waves of Italian Renaissance and Mannerist ideas, fostered by the Wittelsbach dukes' cultural ambitions.

Formal artistic training for Rottenhammer began in 1582 when he became an apprentice in the workshop of Hans Donauer the Elder. Donauer was a significant painter in Munich at the time, known for his work for the court, including decorative schemes and history paintings. Under Donauer's tutelage, which lasted until approximately 1588, Rottenhammer would have learned the fundamentals of drawing, painting techniques, and composition, likely working in a style that blended late Gothic elements with emerging Renaissance influences prevalent in Southern Germany. This foundational training provided him with the technical skills necessary for his future career.

The Italian Sojourn: Venetian Immersion

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his generation, Rottenhammer recognized the necessity of travelling to Italy to complete his artistic education and experience firsthand the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and the innovations of contemporary masters. Around 1589, he embarked on this transformative journey, initially heading towards Venice. The city of lagoons, a thriving centre of art and commerce, was to have a profound and lasting impact on his artistic development.

In Venice, Rottenhammer immersed himself in the study of the great masters of the Venetian School. He was particularly captivated by the dramatic compositions, rich colours, and dynamic brushwork of Jacopo Tintoretto. The opulent scenes and luminous palette of Paolo Veronese also left a significant mark on his evolving style. Furthermore, the influence of artists like Palma Giovane, who continued the grand Venetian tradition, can be discerned in Rottenhammer's handling of figures and mythological narratives. He spent a considerable period in Venice, absorbing these influences and beginning to establish his reputation.

Roman Years and Fruitful Collaborations

Around 1594 or 1595, Rottenhammer moved from Venice to Rome, another essential destination for any artist seeking to understand the roots of classical art and the latest developments in painting. Rome at this time was a melting pot of artists from across Europe. Rottenhammer quickly integrated into the community of Northern artists residing there, a group often referred to informally due to their shared origins and sometimes distinct approaches compared to their Italian counterparts. This period in Rome proved exceptionally productive and crucial for shaping his mature style, particularly through collaboration.

He formed close working relationships with several Flemish artists, most notably the landscape specialists Paul Bril and Jan Brueghel the Elder. This partnership model became a hallmark of Rottenhammer's career. Typically, Bril or Brueghel would paint detailed and atmospheric landscapes, often on copper panels, and Rottenhammer would then add the figures, usually depicting mythological or religious scenes. This division of labour allowed each artist to focus on their strengths, resulting in works of exquisite detail and harmonious composition that were highly sought after by collectors.

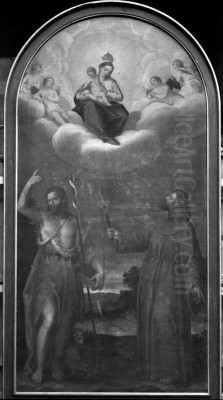

Examples of these successful collaborations include paintings like The Rest on the Flight into Egypt and The Baptism of Christ, where Rottenhammer's elegant, often elongated figures are seamlessly integrated into Brueghel's lush, minutely observed natural settings. These works exemplify the fusion of Flemish landscape tradition with Italianate figure painting. During his time in Rome, Rottenhammer also encountered other significant artists, including the highly influential German painter Adam Elsheimer, who was similarly engaged in creating small-scale, intensely atmospheric works. While perhaps not forming a formal "school," these Northern artists in Rome undoubtedly exchanged ideas and influenced one another. The broader Roman artistic environment included prominent Italian painters like Cavalier d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari) and Federico Zuccaro, whose late Mannerist styles dominated large-scale commissions.

Master of the Cabinet Painting

While capable of working on a larger scale, Hans Rottenhammer became particularly celebrated for his cabinet paintings – small, highly finished works intended for close viewing in private collections or studies ('cabinets'). He frequently chose copper as his support, the smooth, non-absorbent surface of which allowed for exceptional detail, luminous colours, and a jewel-like finish. This format was increasingly popular among sophisticated collectors across Europe who appreciated the intimacy and refinement of such pictures.

Rottenhammer's subject matter for these cabinet pieces drew heavily from classical mythology and biblical narratives. Scenes featuring gods and goddesses, nymphs, satyrs, the Holy Family, or various saints were common. He rendered these subjects with a characteristic elegance, often featuring graceful, somewhat elongated figures arranged in complex, dynamic compositions. His Venetian-inspired use of colour, combined with a Northern European attention to detail, created works that were both sensuous and meticulously crafted.

One notable example reflecting his skill in this genre and his high-level connections is the Feast of the Gods. While several versions exist, his work on this theme, sometimes linked to commissions or acquisitions by Emperor Rudolf II, showcases his ability to handle multi-figure compositions with mythological themes, blending landscape elements (sometimes collaborative) with his distinctive figure style. These small copper paintings became one of his most recognizable contributions and significantly influenced subsequent generations of artists working in this format, particularly in the Netherlands and Flanders.

Imperial Patronage and Recognition

Rottenhammer's talent did not go unnoticed by the highest echelons of society. His reputation, built upon his work in Venice and Rome and disseminated through his sought-after cabinet paintings and collaborations, reached the imperial court in Prague. Emperor Rudolf II, one of the most avid art collectors and patrons of the era, employed Rottenhammer. The Emperor commissioned works from him, such as the aforementioned Feast of the Gods, which suited the sophisticated, often allegorical and mythological tastes of the Prague court.

Beyond direct commissions, Rottenhammer also acted as an agent for Rudolf II in Venice. Leveraging his connections and connoisseurship developed during his years in the city, he was tasked with acquiring paintings by Venetian masters for the Emperor's burgeoning and eclectic collections at Prague Castle. This role underscores the trust placed in Rottenhammer's artistic judgment and his established position within the Venetian art world even after moving to Rome. Later in his career, after returning to Germany, he secured further prestigious appointments, including serving as court painter to Count Ernst von Holstein-Schaumburg in Bückeburg from around 1613 or 1614, demonstrating his continued appeal to noble patrons.

Return to Germany: The Augsburg Years

After a long and formative period in Italy spanning roughly fifteen years, Hans Rottenhammer decided to return to his native Germany around 1606. He chose to settle not in his birth city of Munich, but in the Free Imperial City of Augsburg. Augsburg was a major financial and artistic centre in Southern Germany, boasting a wealthy patrician class and a strong tradition of craftsmanship and art production. Rottenhammer was granted citizenship (or 'freedom of the city') in Augsburg, allowing him to establish his workshop and practice his profession there.

In Augsburg, Rottenhammer continued to produce paintings, including cabinet pictures that remained popular. He also undertook larger-scale commissions, adapting his style to meet local demands. Sources mention his involvement in decorative projects, potentially including ceiling frescoes for prominent buildings, possibly within the context of the magnificent Augsburg Town Hall or related patrician residences like the Schaezlerpalais complex, although specific attributions can be complex. He maintained connections with collaborators, and his workshop likely attracted pupils eager to learn his Italianate style.

However, his later years in Augsburg were not without difficulties. While he initially enjoyed success, competition from other skilled Augsburg artists, such as Johann König, may have intensified. Furthermore, personal struggles began to overshadow his professional life. Despite his established reputation, his productivity seems to have waned compared to his prolific Italian period.

Synthesizing Styles: Rottenhammer's Artistic Signature

Hans Rottenhammer's enduring significance lies in his successful synthesis of diverse artistic currents. His style represents a fascinating blend of the precision and detail characteristic of the Northern European tradition, inherited from his German training, with the colour, light, and compositional dynamism absorbed during his long stay in Italy, particularly Venice. His figures, often slender and elegant, move with a Mannerist grace, yet they are rendered with a clarity and richness of colour that speaks of his Venetian experience.

He excelled in depicting the human form, often showcasing idealized nudes within mythological or allegorical contexts. His compositions are typically well-balanced, even when filled with numerous figures, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of Italian compositional principles. The use of copper as a support enhanced the luminosity of his colours and the meticulousness of his brushwork, contributing to the precious quality of his cabinet paintings. Positioned historically, Rottenhammer's work bridges the gap between late international Mannerism and the emerging Baroque style, incorporating elements of both.

His collaborations with landscape specialists like Paul Bril and Jan Brueghel the Elder were not merely practical arrangements but resulted in a distinct genre where figures and landscape achieved a new level of integration and mutual enhancement. This approach proved highly influential, particularly for Flemish artists who continued this tradition of collaborative landscape and figure painting.

Personal Struggles and Final Years

Despite his artistic achievements and the patronage he enjoyed, Hans Rottenhammer's later life was marked by personal hardship. Contemporary accounts and historical records indicate that he struggled with alcoholism. This addiction likely impacted his ability to consistently fulfill commissions and manage his finances effectively. Joachim von Sandrart, an early German art historian who wrote about Rottenhammer in his Teutsche Academie (1675), noted the artist's decline due to excessive drinking.

These personal difficulties contributed to a decline in his fortunes during his later years in Augsburg. While he had achieved considerable fame and worked for emperors and counts, his struggles prevented him from maintaining the level of success he had experienced earlier. Consequently, Hans Rottenhammer the Elder died in Augsburg in 1625, reportedly in relative poverty, a sad end for an artist who had reached significant heights in the international art world of his time. His death marked the end of a career that had significantly contributed to the transmission of Italian artistic ideas north of the Alps.

Legacy and Influence

Hans Rottenhammer the Elder left a considerable legacy, influencing art both north and south of the Alps. His primary importance lies in his role as a conduit for Italian artistic ideas, particularly Venetian colour and composition, into Germany and the Netherlands. He demonstrated how these elements could be successfully integrated with Northern traditions of detail and finish.

His specialization in highly finished cabinet paintings on copper contributed significantly to the popularity of this genre among collectors. These works were widely disseminated and admired, influencing artists who specialized in small-scale, detailed paintings, such as his contemporary Adam Elsheimer, although Elsheimer developed a distinctively personal style focused on light and atmosphere. Rottenhammer's collaborative method, particularly the combination of his figures with landscapes by specialists like Jan Brueghel the Elder and Paul Bril, set a precedent followed by many Flemish artists, including Hendrik van Balen and Joos de Momper the Younger, and indirectly impacted the workshop practices of major figures like Peter Paul Rubens, who often collaborated with landscape and still-life painters.

Furthermore, Rottenhammer's compositions became known to an even wider audience through reproductive prints made by skilled engravers such as Aegidius Sadeler II and Jan Muller. These prints circulated throughout Europe, spreading his stylistic innovations and popularizing his mythological and religious subjects. Although his later life was troubled, his earlier success and the inherent quality of his work ensured his place as a key figure in European art around 1600, recognized for his elegant synthesis of styles and his contribution to the vibrant artistic exchange of the era.

Conclusion

Hans Rottenhammer the Elder emerges from the historical record as a talented and influential German painter whose career was decisively shaped by his experiences in Italy. From his training in Munich to his immersion in the art of Venice and Rome, he forged a distinctive style characterized by elegant figures, rich colours, and meticulous execution, often realized in the intimate format of cabinet paintings on copper. His collaborations with leading Flemish landscape painters like Paul Bril and Jan Brueghel the Elder produced works of remarkable harmony and detail, influencing the development of that genre. Despite personal struggles later in life, Rottenhammer's art enjoyed international acclaim, attracting patronage from Emperor Rudolf II and other nobles. He remains a significant figure for understanding the complex interplay between Northern European and Italian art at the transition from the late Renaissance and Mannerism to the early Baroque period.