Hendrick Cornelisz van Vliet (c. 1611/1612 – buried 28 October 1675) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born and active primarily in Delft, a city renowned for its vibrant artistic output during the 17th century, Van Vliet carved a distinct niche for himself, particularly through his evocative and meticulously rendered paintings of church interiors. While he also engaged in portraiture and historical subjects, it is his architectural scenes, imbued with a profound understanding of perspective and a subtle interplay of light and shadow, that cemented his reputation and continue to captivate audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Apprenticeship in Delft

Hendrick van Vliet was born in Delft, a bustling center of commerce, innovation, and art. The exact date of his birth is estimated to be around 1611 or 1612. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of his uncle, Willem van der Vliet, a painter of some repute in Delft. This familial connection likely provided young Hendrick with his initial exposure to the techniques and traditions of painting. Willem van der Vliet himself was a versatile artist, known for portraits and historical scenes, which may have influenced Hendrick's early foray into these genres.

Further honing his skills, Hendrick van Vliet is also documented as having studied with Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt. Van Mierevelt was one of the most successful and prolific portrait painters in the Dutch Republic, with an extensive workshop and a clientele that included royalty and prominent citizens. Training under such a distinguished master would have provided Van Vliet with a rigorous grounding in draughtsmanship, composition, and the ability to capture a likeness, skills that would prove invaluable even as he later specialized in architectural painting. The precision required in portraiture, particularly in rendering details of costume and physiognomy, likely translated into his meticulous approach to architectural elements.

In 1632, Hendrick van Vliet achieved a significant milestone in his career by becoming a member of the Guild of St. Luke in Delft. Membership in the guild was essential for artists wishing to practice professionally, take on apprentices, and sell their work. This indicates that by his early twenties, Van Vliet had attained a recognized level of competence and was ready to establish himself as an independent master.

The Rise of Architectural Painting and Van Vliet's Specialization

The 17th century in the Netherlands witnessed the flourishing of various specialized painting genres, including landscape, seascape, still life, genre scenes, and architectural painting. The depiction of church interiors, in particular, gained popularity. This interest can be attributed to several factors, including civic pride in local monuments, the complex spatial challenges these structures presented to artists, and the contemplative or symbolic meanings they could convey. Artists like Pieter Saenredam had already pioneered a style characterized by bright, almost ethereal depictions of church spaces, emphasizing their serene emptiness and architectural purity.

While Van Vliet initially produced portraits, a genre in which his teacher Van Mierevelt excelled, he began to gravitate towards architectural painting, specifically church interiors, around the early 1650s. This shift marked a pivotal point in his career. He joined other Delft artists like Gerard Houckgeest and Emanuel de Witte who were also exploring this theme. However, each developed a distinctive approach. Houckgeest was known for his innovative use of oblique perspectives, creating dynamic and complex spatial arrangements. De Witte, on the other hand, often infused his church interiors with a more atmospheric and dramatic use of light and shadow, frequently populating his scenes with figures engaged in various activities, lending a narrative quality to his work.

Van Vliet developed his own unique style within this burgeoning field. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of the two main churches in his native Delft: the Oude Kerk (Old Church) and the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church). These structures, with their soaring Gothic architecture, intricate details, and historical significance (the Nieuwe Kerk, for instance, houses the tomb of William the Silent, the national hero), provided rich subject matter.

Artistic Style: Perspective, Light, and Atmosphere

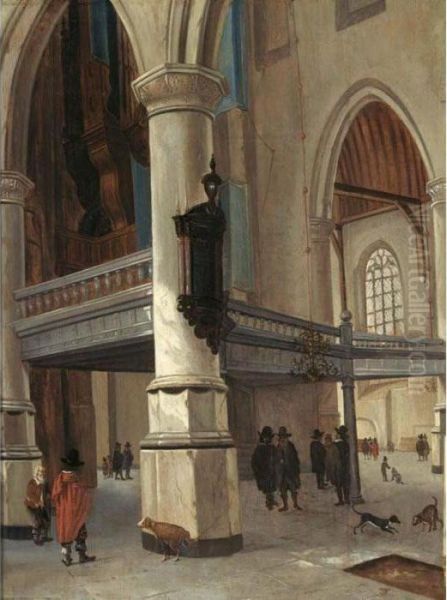

Hendrick van Vliet's church interiors are characterized by their masterful handling of perspective. He employed linear perspective with remarkable accuracy, creating a convincing illusion of depth and space on the two-dimensional canvas. His compositions often lead the viewer's eye deep into the church, past rows of columns, through arches, and towards distant light sources, such as stained-glass windows or illuminated chancels. This precise rendering of space was a hallmark of the Delft school of architectural painters.

Light plays a crucial role in Van Vliet's work. He skillfully depicted the fall of light through windows, illuminating specific areas while leaving others in soft shadow. This interplay of light and dark not only enhances the sense of volume and three-dimensionality but also contributes to the overall mood of the painting. Unlike the often stark, even lighting of Saenredam, or the more dramatic chiaroscuro of De Witte, Van Vliet's lighting is often subtle and nuanced, creating a calm, contemplative atmosphere. His works frequently feature a cool color palette, with a prevalence of greys, browns, and often a distinctive use of greens, which can lend a slightly damp or cool feeling to the depicted interiors, enhancing their realism.

His attention to architectural detail was exacting. Columns, capitals, vaulting, floor tiles, and funerary monuments are rendered with care and precision, almost with a "photographic" quality, as described in some analyses. This meticulousness extended to the textures of stone, wood, and metal. Yet, his paintings are not merely sterile architectural records. He often included small figures – groups of people conversing, individuals in prayer, children playing, or even dogs – which animate the spaces and provide a sense of scale. These figures, though secondary to the architecture, add a human element and hint at the church's role as a place of worship, social interaction, and commemoration.

Van Vliet's compositions are carefully balanced. He often utilized diagonal lines, created by receding rows of columns or the pattern of floor tiles, to guide the viewer's eye and create a sense of dynamic recession. Vertical elements, such as pillars and monuments, provide stability and grandeur. The placement of figures within these vast spaces is also considered, distributing them to enhance the composition and draw attention to different parts of the church.

Themes and Symbolism in Van Vliet's Church Interiors

Beyond their aesthetic appeal and technical virtuosity, Van Vliet's church interiors can also be interpreted as carrying deeper thematic and symbolic weight, common in Dutch art of the period. The churches themselves, as sacred spaces, were potent symbols. In the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic, these buildings, often stripped of elaborate Catholic ornamentation after the Reformation, represented places of communal worship and civic identity.

The inclusion of tombs and funerary monuments, which are prominent features in many of Van Vliet's paintings, serves as a memento mori – a reminder of the transience of life and the inevitability of death. This was a common theme in 17th-century Dutch culture, reflecting a society conscious of mortality due to wars, plagues, and the uncertainties of life. For instance, his depiction of the tomb of William the Silent in the Nieuwe Kerk was not just an architectural study but also a tribute to a key figure in Dutch history and a symbol of national pride and resilience.

The figures within his paintings, though often small, can also contribute to the thematic content. They might represent piety, contemplation, or the everyday life that continued within these sacred precincts. The presence of dogs, for example, was common in Dutch churches at the time and in paintings; while sometimes seen as symbols of fidelity, they could also simply reflect the reality of church life or, in some contexts, carry negative connotations if depicted inappropriately (e.g., urinating, a motif sometimes used by artists like Emanuel de Witte to subtly critique or comment). In Van Vliet's Interior of the Pieterskerk in Leiden (1653), the juxtaposition of tombstones and figures, including a dog, encourages reflection on life, death, and the passage of time.

Although Van Vliet lived in what was described as a Catholic community, he predominantly painted the interiors of Protestant churches. This focus likely reflected the market demand and the visual appeal of these grand, relatively unadorned spaces, which allowed for a greater emphasis on architectural form and the play of light. His work, therefore, provides a valuable visual record of these important religious and civic buildings during a transformative period in Dutch history.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several key works exemplify Hendrick van Vliet's skill and artistic vision:

<em>Interior of the Oude Kerk, Delft</em> (c. 1660, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This painting is a quintessential example of Van Vliet's mature style. It showcases his command of perspective, with the receding lines of the columns and floor tiles drawing the eye towards the brightly lit choir. The cool, silvery light bathes the interior, highlighting the texture of the stone and the intricate details of the architecture. Small figures populate the scene, adding life and scale to the vast space. The painting conveys a sense of serene grandeur and quiet contemplation.

<em>The Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft with the Tomb of William the Silent</em> (c. 1650-1660, Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna): This work focuses on one of Delft's most important monuments. The elaborate tomb of William the Silent, a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture by Hendrick de Keyser, is a central feature. Van Vliet masterfully integrates this complex sculptural element into the broader architectural setting of the Nieuwe Kerk. The painting is a testament to both civic pride and the artist's ability to handle complex spatial relationships and varied textures.

<em>Interior of the Pieterskerk in Leiden</em> (1653, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels): This painting demonstrates Van Vliet's ability to capture the unique character of different churches. The Pieterskerk in Leiden, another significant Gothic structure, is rendered with his characteristic precision. The work is noted for its careful depiction of light filtering through the large windows and the inclusion of various figures, including a gravedigger, which reinforces the memento mori theme often present in his church interiors.

<em>Interior of the Sint-Janskerk at Gouda</em> (c. 1660s): While perhaps less frequently reproduced than his Delft church scenes, Van Vliet also depicted other churches. If this refers to the famous church in Gouda, known for its magnificent stained-glass windows (the "Goudse Glazen"), it would have offered a different challenge in terms of capturing colored light. His painting Interior of St Janskerk (1660) is praised for its handling of light, possibly through curtains, enhancing depth and drama.

<em>View of the Oude Kerk in Delft</em> (1654, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): Interestingly, this work is an exterior view, showcasing a different aspect of Van Vliet's skill. It demonstrates his ability to render the imposing facade of the Oude Kerk and its relationship to the surrounding urban environment. This painting highlights his versatility beyond interior scenes, though interiors remained his primary focus.

<em>The New Church at Delft</em> (Stedelijk Museum Prinsenhof Delft or other collections): Multiple depictions of the Nieuwe Kerk exist, each offering a slightly different viewpoint or lighting condition, underscoring his sustained engagement with this particular subject. These works consistently display his command of perspective and his ability to convey the monumental scale of the church.

These paintings, among others, are now held in prestigious museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna, and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, as well as the Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden (which holds works related to the Pieterskerk).

Contemporaries, Influences, and the Delft Artistic Milieu

Hendrick van Vliet operated within a vibrant artistic community in Delft, which during the mid-17th century was home to some of the Dutch Golden Age's most celebrated painters. Johannes Vermeer, renowned for his luminous genre scenes, Carel Fabritius, known for his experiments with perspective and his tragic death in the Delft gunpowder explosion of 1654, and Pieter de Hooch, famous for his tranquil courtyard and domestic interior scenes, were all active in Delft during Van Vliet's lifetime. While their primary subjects differed, the shared environment likely fostered a climate of artistic innovation and a keen interest in the representation of light and space.

Within the specific genre of architectural painting, Van Vliet's closest contemporaries were Gerard Houckgeest and Emanuel de Witte. As mentioned, Houckgeest was an innovator in using oblique, diagonal views of church interiors, moving away from the more traditional frontal perspectives. De Witte, who also initially worked in Delft before moving to Amsterdam, developed a more atmospheric and often anecdotal style, with a strong emphasis on contrasts of light and shadow and lively human figures. There was undoubtedly a degree of artistic dialogue and perhaps competition among these artists as they explored similar subjects. Van Vliet's style can be seen as occupying a middle ground: less stark than Saenredam, less overtly dramatic in perspective than Houckgeest, and often more subdued in its lighting and narrative content than De Witte's later works.

His early training with portraitist Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt was foundational. While Van Vliet later specialized elsewhere, the discipline of portraiture, with its emphasis on accurate observation and rendering, would have served him well. Other artists who influenced the broader field of architectural painting include earlier figures like Hans Vredeman de Vries, whose influential publications on perspective and architectural ornament laid theoretical groundwork for later generations. The legacy of precise observation and rendering can also be seen in the work of other Dutch painters, even those in different genres, such as the meticulous still life painters like Willem Claesz. Heda or the detailed townscapes of Jan van der Heyden.

Van Vliet's work, in turn, had an influence on subsequent painters of architectural scenes. Artists like Isaac van Nickelen continued the tradition of depicting church interiors, drawing upon the conventions and techniques established by Van Vliet and his contemporaries. The enduring appeal of these serene and meticulously crafted spaces speaks to the success of Van Vliet's artistic vision.

Later Life, Family, and Legacy

Hendrick van Vliet spent his entire life in Delft. In 1643, he married Cornelia van der Plaats. The couple had at least one daughter, also named Cornelia, who was baptized in the Nieuwe Kerk in 1646. He resided at various addresses in Delft, including on the Kromstraat and later on the Oude Delft, one of the city's main canals.

Despite his artistic achievements and his contribution to a popular genre, Van Vliet's later years appear to have been marked by financial hardship. He died in poverty in Delft and was buried in the Oude Kerk – one of the very subjects he had so often painted – on October 28, 1675. The circumstances of his impoverished end are not uncommon among artists of the period, where fame did not always translate into lasting financial security.

Despite the difficulties of his later life, Hendrick van Vliet left behind a significant body of work that continues to be admired for its technical skill, its serene beauty, and its value as a historical record of some of the Netherlands' most important ecclesiastical buildings. His paintings offer a window into the spiritual and civic life of the Dutch Golden Age. He masterfully captured not just the stone and glass of these structures, but also a sense of their enduring presence and the human activities that unfolded within their hallowed walls.

His contribution lies in his ability to blend meticulous architectural accuracy with a subtle sensitivity to light and atmosphere, creating images that are both informative and deeply evocative. He stands as a key representative of the Delft school of architectural painting, a specialized but significant branch of Dutch Golden Age art. His works remind us of the period's fascination with perspective, light, and the representation of space, as well as the complex interplay of religious belief, civic pride, and artistic expression in 17th-century Holland. The enduring presence of his paintings in major international collections ensures that his unique vision of sacred spaces continues to be appreciated by art lovers and historians alike.