Cornelis de Man (1621–1706) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Active primarily in Delft, a city renowned for its artistic innovation, De Man contributed a distinctive voice through his meticulously rendered genre scenes, insightful portraits, and atmospheric church interiors. His work, while clearly influenced by celebrated contemporaries, possesses a unique character that reflects both the artistic currents of his time and his personal vision. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, key works, and his position within the vibrant art scene of 17th-century Holland.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Delft

Born in Delft in July 1621, Cornelis de Man entered a world where the Dutch Republic was at the zenith of its economic and cultural power. Delft itself was a bustling center of commerce, industry (notably ceramics), and art. While concrete details about his earliest training are scarce, it is known that he was born into a family that may have had connections to the jewelry trade. This background, coupled with a close association with the church, suggests a respectable, perhaps even somewhat formidable, social standing. Such connections could have provided both financial stability and access to potential patrons.

De Man's formal entry into the artistic community of Delft is marked by his admission to the Guild of Saint Luke in 1642. This guild was the cornerstone of artistic life in Dutch cities, regulating the training of artists, the quality of their work, and their ability to sell it. Membership was essential for any painter wishing to establish a professional career. His acceptance into the guild signifies that he had completed an apprenticeship, likely under a recognized Delft master, though the identity of this master remains a subject of speculation. Some scholars suggest early exposure to the works of artists like Leonard Bramer, known for his dramatic use of light and historical scenes, might have played a role.

The Grand Tour: Italian Sojourns and Broadening Horizons

Shortly after becoming a master in the Delft guild, Cornelis de Man embarked on an extended period of travel, a common practice for ambitious Northern European artists seeking to broaden their artistic education and experience. His journey, lasting approximately nine years, took him primarily to Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and a continuing source of inspiration for artists across Europe. He is documented as having worked in Paris, perhaps as an initial stop or a later one on his return.

His Italian sojourn included significant periods in Florence, Rome, and Venice. Each city offered unique artistic stimuli. In Florence, he would have encountered the masterpieces of the High Renaissance, particularly the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, and the intellectual rigor of Florentine design (disegno). Rome, with its unparalleled classical ruins and the powerful art of the Baroque, including the revolutionary naturalism of Caravaggio and the classical grandeur of Annibale Carracci and his followers, would have been profoundly impactful. The vibrant color (colore) and atmospheric light of Venetian painters, from Titian and Veronese to their 17th-century successors, likely also left a lasting impression.

While direct stylistic imitations of specific Italian masters are not always overt in De Man's later work, this extended period abroad undoubtedly refined his technique, expanded his thematic repertoire, and exposed him to diverse approaches to composition, color, and light. Some of his later church interiors and even certain landscape elements hint at an Italianate sensibility, particularly in the handling of architectural space and atmospheric perspective.

Return to Delft: A Respected Master and Guild Leader

Cornelis de Man returned to his native Delft around 1653 or 1654, a mature artist with a wealth of experience. He re-established himself within the city's artistic community and became a respected figure. His standing is evidenced by his repeated election as head (hoofdman) of the Guild of Saint Luke, a position of considerable responsibility and prestige. This role involved overseeing the guild's affairs, upholding its standards, and representing its members. His leadership suggests he was not only a skilled painter but also a capable administrator and a respected peer.

Delft in the mid-17th century was an extraordinary hub of artistic activity. It was during this period that Johannes Vermeer was creating his luminous and enigmatic masterpieces, and Pieter de Hooch was pioneering his tranquil and light-filled domestic interiors. Carel Fabritius, a brilliant pupil of Rembrandt, had also been active in Delft until his tragic death in the 1654 gunpowder explosion. The city's artistic environment was characterized by a keen interest in perspective, the subtle effects of light, and the depiction of everyday life with quiet dignity. De Man was an active participant in this milieu, absorbing its influences while contributing his own distinct perspective.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Cornelis de Man's oeuvre is diverse, encompassing genre scenes, portraits (both individual and group), church interiors, and, to a lesser extent, landscapes and even a unique depiction of industrial activity. A common thread throughout his work is a meticulous attention to detail, a refined technique, and a thoughtful approach to composition.

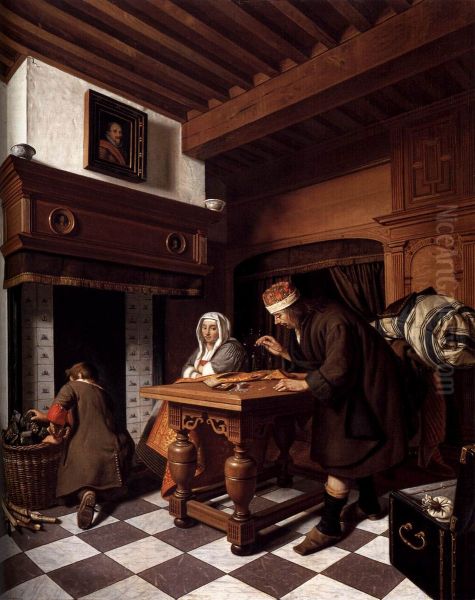

His genre scenes, often depicting the interiors of prosperous middle-class homes, are perhaps his most characteristic works. These paintings share certain affinities with those of Vermeer and De Hooch, particularly in their focus on domesticity, the play of light through windows, and the careful rendering of textures – polished wood, rich fabrics, gleaming metal. However, De Man's figures often have a more solid, sometimes even slightly more rigid, quality than Vermeer's, and his narratives can be more explicit than the often-ambiguous scenes of his famed contemporary. He frequently depicted scholars in their studies, gentlemen engaged in intellectual pursuits, or families in moments of quiet interaction. Works like The Card Players or The Curious Seller exemplify his skill in this area, capturing moments of everyday life with a sense of order and calm.

In his portraiture, De Man demonstrated an ability to capture a sitter's likeness with accuracy and dignity. He often portrayed individuals from Delft's professional and intellectual circles, including clergy and scholars. These portraits are typically characterized by a sober palette and a focus on the sitter's status and character. An interesting feature noted by art historians is his use of "speaking hands" – expressive hand gestures that convey emotion or character, perhaps compensating for a sometimes more reserved facial expression. This was a convention seen in earlier portraiture but employed effectively by De Man.

His church interiors, such as views of the Oude Kerk or Nieuwe Kerk in Delft, align with a popular Dutch genre. These paintings, influenced by artists like Gerard Houckgeest and Emanuel de Witte (both of whom also worked in Delft), are not merely architectural records but also explorations of light, space, and spiritual atmosphere. De Man excelled at conveying the vastness of these sacred spaces and the intricate play of light filtering through their stained-glass windows.

Key Masterpieces and Notable Works

Several paintings stand out in Cornelis de Man's body of work, showcasing his skill and thematic interests.

_The Whale Oil Refinery on Spitsbergen (Smeerenburg)_ (c. 1639, though some sources date it later): This is one of De Man's most unusual and fascinating paintings. It depicts the bustling activity of a Dutch whaling station in the Arctic. What makes it particularly noteworthy is that De Man himself never traveled to Spitsbergen. He based the composition on existing prints, drawings, and written accounts. The painting is a testament to the Dutch engagement in global trade and industry, and De Man's ability to create a convincing and detailed scene from secondary sources. The meticulous rendering of the try-works, the flensing of whales, and the various figures engaged in labor is remarkable. This work highlights a broader Dutch interest in documenting their expanding world, even its most remote corners.

_Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Cornelis van Gravensande_ (1681): This large group portrait is a prime example of a genre particularly popular in the Netherlands, celebrating scientific inquiry and civic pride. It depicts Dr. van Gravensande, a prominent Delft physician, demonstrating an anatomical dissection to a group of surgeons. De Man skillfully arranges the figures, giving each a distinct presence while maintaining a cohesive composition. The work can be compared to Rembrandt's famous Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, though De Man's approach is perhaps more straightforward and less dramatically lit. It is a significant historical document as well as an accomplished piece of painting, now housed in the Museum Prinsenhof Delft.

_Allegory of the Virtuous Life_ (1682): This work, also in the Museum Prinsenhof Delft, demonstrates De Man's capacity for more complex, symbolic compositions. Allegorical paintings were common in the Dutch Golden Age, often conveying moral lessons through a visual language of symbols and personifications. This painting likely draws on established iconographic traditions to represent virtues and their rewards.

_Interior with a Scholar at his Desk_ (various versions and similar themes): De Man frequently returned to the theme of the scholar in his study. These paintings often feature a solitary male figure surrounded by books, globes, scientific instruments, and other accoutrements of learning. The settings are meticulously detailed, with careful attention paid to the fall of light on different surfaces. These works reflect the high value placed on education and intellectual pursuits in Dutch society. A notable example is Man Weighing Gold, which, with its contemplative figure and careful balance of objects, has drawn comparisons to certain works by Vermeer, such as Woman Holding a Balance.

_Collective Portrait at the Apothecary's in Delft_ (c. 1670): Now in the National Museum in Warsaw, this group portrait showcases De Man's ability to manage complex compositions with multiple figures in an interior setting. It provides a fascinating glimpse into a professional environment of the time, detailing the interior of an apothecary shop and the individuals associated with it. Such works served not only as records of individuals but also as statements of professional identity and communal association.

_The Card Players_ and _The Curious Seller_: Both housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, these paintings are excellent examples of De Man's genre scenes. The Card Players captures the quiet concentration and subtle social dynamics of a game, while The Curious Seller depicts an interaction within a domestic interior, rich with details of everyday objects and furnishings. These works demonstrate his skill in creating believable spaces and engaging, albeit understated, human interactions.

Influences and Contemporaries: A Web of Connections

Cornelis de Man operated within a dynamic artistic landscape, and his work inevitably reflects the influence of his contemporaries, while also contributing to the broader artistic discourse.

The most frequently cited influences are Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684). Both were his near-contemporaries in Delft. De Hooch's mastery of complex interior perspectives, his depiction of tranquil domestic scenes, and his innovative use of doorkijkjes (see-through views into other rooms or courtyards) certainly provided a model for many Delft painters, including De Man. Vermeer's unparalleled handling of light, his serene and psychologically nuanced figures, and his refined compositions set a standard of excellence that resonated throughout Delft. While De Man did not achieve Vermeer's almost magical luminosity, the shared interest in light-filled interiors and quiet human moments is evident.

Beyond these key Delft figures, De Man would have been aware of broader trends in Dutch painting. The detailed realism and moralizing undertones in the genre scenes of artists like Gerard Dou (1613–1675), a founder of the Leiden "fijnschilders" (fine painters), or the more boisterous and anecdotal scenes of Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679), who also worked in Delft for a period, would have been part of the artistic vocabulary of the time. The elegant interiors and sophisticated figures of Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) and Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667) also set high standards for genre painting.

In portraiture, De Man's work can be seen in the context of artists like Frans Hals (c. 1582/83–1666) from Haarlem, known for his lively and characterful portraits, though De Man's style was generally more restrained. In Amsterdam, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) and his pupils, such as Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) in his earlier genre-painting phase, were producing powerful portraits and narrative scenes that influenced Dutch art profoundly.

The tradition of church interior painting, in which De Man also participated, had prominent exponents like Pieter Saenredam (1597–1665), known for his precise and light-filled architectural views, and, as mentioned, Gerard Houckgeest (c. 1600–1661) and Emanuel de Witte (c. 1617–1692), who brought a greater sense of atmosphere and human presence to the genre. De Man's contributions to this field show a similar concern for accurate architectural rendering combined with an appreciation for the play of light within these expansive structures.

While direct collaborations are not extensively documented, the close-knit nature of the guilds and the relatively small size of cities like Delft meant that artists were undoubtedly aware of each other's work, leading to mutual influence and a shared artistic evolution. De Man's leadership role in the guild would have placed him at the center of these interactions. There is no strong evidence of overt competition in a negative sense; rather, the environment seems to have fostered a high level of artistic achievement through shared interests and a collective pursuit of excellence.

Anecdotes and Lesser-Known Facets

While Cornelis de Man's life is not as extensively documented as some of his more famous contemporaries, a few interesting details and observations emerge. His family's possible connection to the jewelry trade and their close ties to the church paint a picture of a man embedded in the respectable, perhaps somewhat conservative, strata of Delft society. This might explain the often sober and dignified tone of his portraits and genre scenes.

The story of his painting The Whale Oil Refinery on Spitsbergen being created without a personal visit to the Arctic is a fascinating testament to an artist's ability to synthesize information and create a vivid reality from secondary sources. It also underscores the Dutch fascination with their global reach and industrial prowess during this period. His travels, though not extending to the far north for this particular subject, were extensive in Europe, particularly his nine-year stay in Italy, which must have been a formative experience.

The observation about his use of "speaking hands" in portraiture is a subtle but insightful point made by art historians like Hofstede de Groot, who was instrumental in "rediscovering" De Man's work for modern audiences around 1903. Before this, De Man had been a somewhat forgotten figure. This rediscovery highlights how art historical scholarship can bring deserving artists back into the light.

His multiple tenures as head of the St. Luke's Guild in Delft underscore his importance within the local artistic community. He was clearly a pillar of that community, entrusted with leadership by his peers. This suggests a man of good standing, organizational skill, and respected artistic judgment.

Later Years, Legacy, and Surviving Works

Cornelis de Man continued to live and work in Delft throughout his long life. He passed away in Delft on September 1, 1706, at the advanced age of 85, having witnessed the peak of the Dutch Golden Age and its gradual transition.

His legacy is that of a skilled and versatile painter who contributed significantly to the Delft School. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary genius of Vermeer, he was a highly accomplished artist who produced works of lasting quality and historical interest. His paintings provide valuable insights into the life, values, and aesthetics of 17th-century Dutch society.

Many of Cornelis de Man's works are now held in public collections, primarily in the Netherlands but also internationally.

Key institutions include:

Museum Prinsenhof Delft: Holds significant works like Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Cornelis van Gravensande and Allegory of the Virtuous Life.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: Houses important genre scenes such as The Card Players and The Curious Seller, as well as the iconic The Whale Oil Refinery on Spitsbergen.

National Museum, Warsaw: Home to the Collective portrait at the apothecary's in Delft.

Other museums in the Netherlands and abroad also possess examples of his work, including portraits and church interiors.

Exhibition History and Modern Reception

In recent times, Cornelis de Man's works have been included in various exhibitions focusing on Dutch Golden Age art or specific themes. For instance, his Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Cornelis van Gravensande was featured in a 2019 exhibition titled "The Art of Anatomy," which explored the intersection of art and anatomical science. The inclusion of his Collective portrait at the apothecary's in Delft in contexts related to costume history or professional group portraiture further highlights the diverse relevance of his oeuvre.

The renewed scholarly attention, initiated by figures like Hofstede de Groot, has helped to secure Cornelis de Man's place in art history. He is recognized as a fine representative of the Delft School, admired for his technical skill, his thoughtful compositions, and his ability to capture the character of his time. His paintings continue to be studied for their artistic merit and as valuable documents of 17th-century Dutch culture.

Conclusion: A Delft Master Reconsidered

Cornelis de Man was a dedicated and talented artist who made a substantial contribution to the rich artistic heritage of the Dutch Golden Age. His meticulous genre scenes offer intimate glimpses into the lives of the prosperous Dutch middle class, his portraits capture the dignity and character of his sitters, and his church interiors evoke the serene grandeur of sacred spaces. Influenced by the artistic currents of Delft and his experiences abroad, particularly in Italy, he forged a distinctive style characterized by careful execution, thoughtful composition, and an acute observation of detail. As a respected leader of the Delft Guild of Saint Luke and a painter of considerable skill, Cornelis de Man remains an important figure for understanding the breadth and depth of artistic production in one of history's most vibrant cultural periods. His works continue to engage viewers with their quiet charm and their window onto a bygone era.