Henri Lehmann, born Karl Ernest Rudolf Heinrich Salem Lehmann, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A German by birth who became a naturalized French citizen, Lehmann was a devoted pupil of the great Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Throughout his career, he championed the academic tradition, producing a substantial body of work encompassing historical subjects, religious scenes, and, most notably, refined portraits. His influence extended beyond his own canvases, as he became an important teacher at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, shaping a generation of artists, some of whom would later diverge dramatically from his classical tenets.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on April 14, 1814, in Kiel, located in the Duchy of Holstein, then under Danish rule, Henri Lehmann's artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age. His father, Leo Lehmann (1782–1859), himself a painter, provided his son with his initial instruction in the arts. This early exposure within a familial artistic environment undoubtedly laid the groundwork for his future pursuits. However, the ambitious young artist recognized that Paris was the epicenter of the art world in the early 19th century.

In 1831, at the tender age of seventeen, Lehmann made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. This move was not merely a change of scenery but a profound step towards immersing himself in the most dynamic artistic currents of the time. He sought out the tutelage of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who was then one of the most revered and influential artists in France, the standard-bearer of Neoclassicism against the rising tide of Romanticism, championed by artists like Eugène Delacroix.

Under the Wing of Ingres

Lehmann quickly distinguished himself in Ingres's studio, becoming one of his master's most dedicated and accomplished pupils. Ingres's pedagogy emphasized rigorous drawing, the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters like Raphael, and a profound respect for line and clarity of form. Lehmann absorbed these principles deeply, and they would become the bedrock of his artistic style throughout his life. He maintained a close and enduring relationship with Ingres, not just as a student but as a collaborator and a lifelong admirer.

The impact of Ingres on Lehmann cannot be overstated. He learned the meticulous technique, the emphasis on idealized beauty, and the intellectual rigor that characterized Ingres's oeuvre. This period of intense study and practice shaped Lehmann's artistic identity, aligning him firmly with the Neoclassical tradition. His contemporaries in Ingres's studio included other talented artists who would also make their mark, such as Hippolyte Flandrin and Théodore Chassériau, though Chassériau would later develop a style that blended Ingres's linearity with Delacroix's color and Romantic fervor.

Lehmann's official artistic career began to take shape with his debut at the Paris Salon of 1835. At this prestigious annual exhibition, he presented his work and was awarded a second-class medal, a significant recognition for a young artist. This initial success was a harbinger of future accolades. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon, a crucial venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage.

The Roman Sojourn and Maturing Vision

A period of study in Rome was considered an essential part of a classical artist's education. From 1838 to 1841, Lehmann resided in Rome, a city steeped in classical antiquity and Renaissance grandeur. Ingres himself was the Director of the French Academy in Rome at the Villa Medici during part of this time, and Lehmann benefited from his continued presence and guidance.

His time in Italy was not solely dedicated to the solitary study of ancient ruins and masterpieces. It was also a period of vibrant social and intellectual exchange. Lehmann formed significant friendships with prominent figures in the artistic and cultural circles of Rome. Among these were the celebrated composer and pianist Franz Liszt and the writer Marie d'Agoult (who wrote under the pen name Daniel Stern), Liszt's companion. He also encountered other luminaries, reportedly including the composer Frédéric Chopin and the writer Stendhal. These connections enriched his personal life and provided him with subjects for his burgeoning portrait practice.

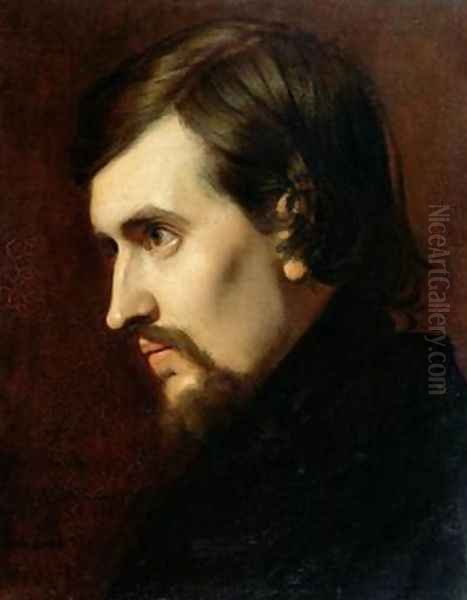

One of his most famous works from this period is the Portrait of Franz Liszt (1839), now housed in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. This painting captures the romantic intensity of the composer, yet it is rendered with the classical precision and elegance that Lehmann had imbibed from Ingres. He also painted several portraits of Marie d'Agoult, including the notable Portrait of Marie de Flavigny, Comtesse d'Agoult. These portraits are characterized by their refined execution, psychological insight, and graceful depiction of the sitters.

Upon his return from Italy, Lehmann's reputation continued to grow. He received further acclaim at the Salon, winning first-class medals in 1840, 1848, and 1855. These awards solidified his position as a leading academic painter in Paris.

A Celebrated Painter in Paris: Portraits and Grand Decorations

Settling permanently in Paris in 1842, Lehmann embarked on a prolific career. He became highly sought after as a portraitist, capturing the likenesses of many distinguished individuals of his era. His portraits were admired for their elegant lines, meticulous detail, and the dignified manner in which he presented his subjects. Beyond the celebrated portraits of Liszt and d'Agoult, he painted his master in the Portrait of Ingres, a testament to their enduring bond. Other notable portraits include those of Anselme, Clémentine Caire, and Faustine Olie.

Lehmann's talents were not confined to easel painting. He received numerous commissions for large-scale public works, a mark of significant official recognition. These monumental decorative schemes allowed him to engage with historical, allegorical, and religious themes on a grand scale, following in the tradition of Renaissance masters.

He created significant murals for the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) in Paris, completed around 1852. These works, unfortunately, were destroyed during the Paris Commune in 1871, a fate shared by many artistic treasures in the building. He also executed important decorative cycles for religious edifices, including the Church of Sainte-Clotilde, where he painted The Adoration of the Magi and Shepherds, and the Saint-Merri Church, for which he painted murals including a depiction of Jean-Louis Gabriel, Curé of Saint-Merry.

Perhaps his most extensive public commission was for the Palais du Luxembourg, which housed the French Senate. He was tasked with decorating the Salle du Trône (Throne Room, later known as the Salle des Conférences). These murals, depicting scenes from the history of France, showcased his mastery of composition and his ability to handle complex multi-figure narratives in the grand academic style. These works, such as The Dream of Er (inspired by Plato) and compositions illustrating the sources of French law and glory, remain significant examples of official art during the Second Empire and early Third Republic.

His historical and mythological paintings also garnered attention. Works like Grief of the Oceanides at the Foot of the Rock where Prometheus Lies Enchanted, exhibited at the Salon of 1850, demonstrated his engagement with classical literature and his ability to convey dramatic emotion within a controlled, classical framework. Other thematic works included Saint Catherine of Alexandria Carried to Her Tomb by Angels, Hamlet, and Leonidas, showcasing his range across religious, literary, and ancient historical subjects. Tobias Bringing His Bride Sarah to the House of His Father, Tobit and La Nativité (c. 1857) further illustrate his contributions to religious painting. An earlier work, "Oriental" Woman (1837), now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., reflects the contemporary fascination with Orientalist themes, albeit rendered with his characteristic precision.

In 1846, Lehmann's contributions to French art were recognized with the award of the Legion of Honour. The following year, in 1847, he officially became a French citizen, cementing his ties to his adopted country.

Lehmann's Artistic Style: The Ingresque Ideal

Henri Lehmann's artistic style remained remarkably consistent throughout his career, deeply rooted in the Neoclassical principles of his teacher, Ingres. His work is characterized by a primacy of line, meticulous draftsmanship, smooth and polished surfaces, and carefully balanced compositions. Color, while present and often harmonious, was generally subordinate to drawing. This "Ingresque" approach emphasized clarity, order, and an idealized representation of form, drawing inspiration from classical sculpture and High Renaissance painting, particularly the works of Raphael.

His figures are often statuesque, imbued with a sense of calm dignity, even in moments of drama. There is a palpable intellectualism in his art; subjects were carefully chosen from history, mythology, religion, or literature, and rendered with iconographic precision. This academic approach stood in contrast to the emotional intensity and vibrant colorism of Romantic painters like Delacroix, or the unvarnished realism of Gustave Courbet, who was challenging the established artistic hierarchies during Lehmann's mature career.

While Lehmann was a staunch defender of the academic tradition, his work was not devoid of sensitivity. His portraits, in particular, often reveal a subtle psychological depth, capturing the character of his sitters beyond mere physical likeness. The elegance and refinement of his brushwork lent an air of sophistication to his subjects. Even in his large-scale historical and religious compositions, there is a clarity of narrative and a harmonious arrangement of figures that speaks to his mastery of academic principles.

The Educator: Lehmann at the École des Beaux-Arts

Beyond his own artistic production, Henri Lehmann played a crucial role as an educator. In 1861, he was appointed head of a studio (chef d'atelier) at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and in 1875, he was elevated to the position of Professor of Painting. The École was the bastion of academic art training in France, and its professors wielded considerable influence over aspiring artists.

Lehmann's teaching methods were, unsurprisingly, grounded in the academic tradition he espoused: rigorous training in drawing from the live model and plaster casts, the study of anatomy, perspective, and the copying of Old Masters. He sought to instill in his students the same discipline and respect for classical principles that Ingres had instilled in him.

Among his many students were several who would go on to achieve significant fame, though often by reacting against the very academicism Lehmann represented. Most notably, Georges Seurat, the future pioneer of Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism), studied under Lehmann. While Seurat would ultimately forge a radically different artistic path, his early training under Lehmann provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and composition.

Another prominent student was Camille Pissarro, who would become a key figure in the Impressionist movement. Pissarro's experience in Lehmann's studio was reportedly less congenial; he found the academic approach stifling. Indeed, there's an anecdote suggesting that Lehmann and some of his students (or perhaps Lehmann as a student of Ingres, the accounts vary) co-signed a letter protesting the innovative style of Édouard Manet, whose work was seen as a challenge to academic conventions. This highlights the growing divide between the established academic artists and the emerging avant-garde. Despite these tensions, Lehmann's role as an educator was significant, and his studio was a training ground for many young artists.

His commitment to artistic excellence and education was further demonstrated by his establishment of the "Prix Lehmann" (Lehmann Prize), an award intended to recognize and encourage academic achievement in the arts.

Later Years, Honours, and Enduring Legacy

Henri Lehmann continued to be a respected figure in the Parisian art world throughout his later years. His dedication to the classical tradition, even as new artistic movements like Impressionism were gaining momentum, marked him as a stalwart of academic values. In 1864, he made another trip to Italy, this time in his capacity as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, revisiting the sources of classical inspiration.

In 1875, a significant honor was bestowed upon him when he was elected a member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, part of the Institut de France. This was the ultimate recognition of his status within the French artistic establishment.

Henri Lehmann passed away in Paris on March 30, 1882, at the age of 67 (not 79 as some sources mistakenly suggest, given his birth year of 1814). He left behind a substantial body of work and a legacy as a dedicated artist and influential teacher.

While Lehmann's art may not have possessed the revolutionary fervor of some of his contemporaries like Courbet or Manet, nor the dazzling light of Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, his contribution to 19th-century French art is undeniable. He was a master of the academic style, a faithful disciple of Ingres who upheld the traditions of classical beauty, meticulous craftsmanship, and intellectual rigor. His portraits remain elegant testimonies to the personalities of his era, and his public murals, where they survive, are important examples of official art.

His influence as a teacher, though sometimes met with resistance by students eager for new forms of expression like Pissarro or Seurat, provided a foundational training that even these innovators built upon or reacted against. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, another prominent academic painter (though not a direct student of Lehmann, but certainly a contemporary working within similar academic circles influenced by figures like Paul Delaroche and Ingres), shared a commitment to historical accuracy and polished technique, representing the dominant artistic taste for much of the century.

Conclusion: A Steadfast Classicist in a Changing World

Henri Lehmann's career spanned a period of immense artistic change and upheaval. He remained a steadfast adherent to the Neoclassical ideals inherited from Ingres, producing works of refined elegance and technical mastery. As a painter of historical subjects, religious scenes, and, above all, distinguished portraits, he carved out a significant niche for himself in the competitive Parisian art world. His role as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts further extended his influence, shaping, whether through adherence or rebellion, the next generation of artists.

Today, while the avant-garde movements that emerged during his lifetime often dominate historical narratives, a fuller understanding of 19th-century art requires acknowledging the enduring power and prestige of the academic tradition, of which Henri Lehmann was a distinguished representative. His work serves as a vital link in the chain of classical art, a testament to the enduring appeal of line, form, and idealized beauty in an era of burgeoning modernity. He remains a key figure for understanding the Ingresque lineage and the complex artistic dialogues of his time.