Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres stands as a colossus in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in Montauban on August 29, 1780, and living until January 14, 1867, his long life spanned tumultuous periods in French history, from the Revolution through the Napoleonic era and beyond. Ingres became the most significant standard-bearer for French Neoclassicism in the decades after its initial champion, Jacques-Louis David. Renowned for his unwavering devotion to the classical tradition, his exceptional skill in drawing, and his mastery of portraiture, Ingres carved a unique and often controversial path, leaving behind a vast body of work and a profound legacy that continues to resonate. He considered himself primarily a history painter, upholding the highest genre in the academic hierarchy, yet it is arguably his portraits and his distinctive treatment of the female nude that cemented his fame.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Ingres's artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age. His father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres, was a versatile if minor provincial artist, skilled in sculpture, painting, and even music. Recognizing his son's prodigious talent, Joseph Ingres provided his earliest instruction and unwavering support. His mother, Anne Moulet, came from a more modest background, described in some accounts as a nearly illiterate milliner, highlighting the determined effort required by his father to foster his son's artistic ambitions amidst limited means. This early exposure to multiple arts, including music (Ingres became a talented violinist), likely contributed to the sense of harmony and rhythm evident in his later visual work.

Formal training began at the Academy of Arts in Toulouse, where Ingres demonstrated remarkable promise. Seeking broader horizons, he traveled to Paris in 1797, securing a coveted place in the studio of Jacques-Louis David, the preeminent painter of the era and a leading figure of Neoclassicism. David's studio was the crucible of French art, and Ingres absorbed his master's rigorous emphasis on drawing, classical composition, and morally uplifting subject matter, derived from the principles advocated by earlier figures like Anton Raphael Mengs and the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

Ingres fully embraced David's teaching system, which emphasized a return to nature and the study of classical antiquity. However, even as a student, hints of his independent spirit emerged. While mastering the Neoclassical idiom, some later reflected that David's structured system, though complete, might not have entirely suited the "vast and complex physical and mental needs" of Ingres. Despite this, his talent flourished, and in 1801, he achieved the highest honor for a young French artist: the prestigious Prix de Rome, for his painting The Ambassadors of Agamemnon Visiting Achilles. This award granted him a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome, though due to strained government finances, his departure was delayed for several years.

The Crucial Roman Years

Ingres finally arrived in Rome in 1806, embarking on a period that would prove fundamental to his artistic development. The Eternal City, with its layers of history and art, was a revelation. He immersed himself in the study of Greco-Roman sculpture and, perhaps even more significantly, the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the works of Raphael. Raphael became Ingres's lifelong artistic idol, embodying for him the pinnacle of harmony, grace, and idealized beauty achieved through perfect drawing.

During his time in Rome, initially at the Villa Medici (home of the French Academy), and later during an extended stay in Italy that lasted until 1824 (including four years in Florence from 1820), Ingres produced works that began to define his mature style. Paintings like Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808) and the Valpinçon Bather (1808) showcase his developing mastery of line, his ability to render form with sculptural clarity, and a growing sensuousness, particularly in his treatment of the nude.

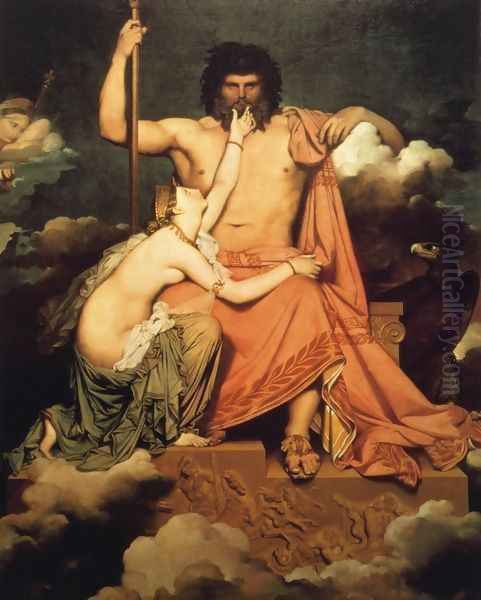

His Jupiter and Thetis (1811), submitted to Paris as proof of his progress, met with a critical reception that foreshadowed future controversies. While demonstrating his classical learning, its stylistic quirks – the elongated, almost boneless form of Thetis, the hieratic stiffness of Jupiter – deviated from strict Davidian Neoclassicism and puzzled the Parisian establishment. Some critics detected unconventional, almost "primitive" or "Gothic" elements, while others perhaps sensed an underlying romantic sensibility in its emotional intensity, despite Ingres's later vehement opposition to Romanticism. During this period, he also formed important friendships, including one with the Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini, who shared his admiration for early Renaissance art.

Return to France and Academic Ascendancy

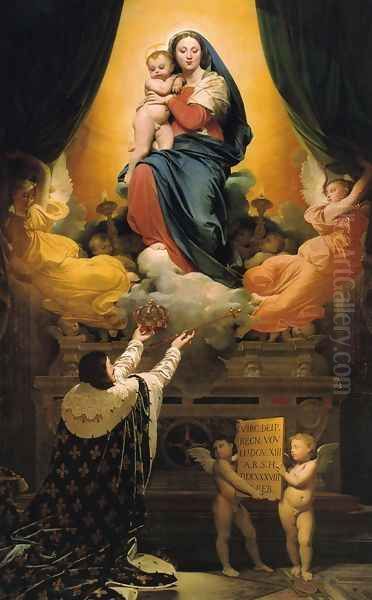

After nearly two decades in Italy, Ingres returned to Paris in 1824. His return coincided with the exhibition of his monumental religious painting, The Vow of Louis XIII, at the annual Salon. Commissioned for the cathedral in his hometown of Montauban, the painting was a resounding success. Its Raphaelesque composition and pious sentiment struck a chord in Restoration France, contrasting sharply with the turbulent energy of Eugène Delacroix's Massacre at Chios, exhibited at the same Salon. Delacroix was rapidly emerging as the leader of the new Romantic school, characterized by its emphasis on color, emotion, and contemporary events.

The triumph of The Vow of Louis XIII marked a turning point. Ingres was hailed as the leading champion of the classical tradition against the perceived excesses of Romanticism. He was awarded the Legion of Honour and, crucially, elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts. Commissions began to flow, including official portraits and grand history paintings. One notable early commission, predating his return but solidifying his connection to power, was the imposing Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne (1806), a work whose rigid frontality and meticulous detail drew comparisons to Byzantine icons and the work of early Netherlandish masters like Jan van Eyck.

Ingres quickly became a dominant figure in the French art world, establishing a large and influential teaching studio. He was seen, and saw himself, as the defender of true artistic principles – clarity, order, the primacy of drawing, and the study of the antique and the High Renaissance masters – against the perceived chaos and individualism of Romanticism.

Ingres the Unrivaled Portraitist

Despite his unwavering commitment to history painting as the noblest form of art, Ingres achieved perhaps his most enduring fame through his portraits. Throughout his career, he produced a remarkable series of likenesses, primarily in oils but also in exquisitely refined graphite drawings, that stand among the greatest achievements in the genre. His portraits are characterized by an astonishing precision of line, a profound psychological acuity, and an uncanny ability to capture the textures of fabrics and the specific character of his sitters, all while adhering to his Neoclassical ideals of clarity and formal elegance.

His sitters were often members of the affluent bourgeoisie, aristocracy, or fellow artists and intellectuals. The Portrait of Monsieur Bertin (1832) is a landmark, capturing the shrewdness and solid presence of the influential journalist with uncompromising realism, yet contained within a powerful, stable composition. Other masterpieces include the graceful Comtesse d'Haussonville (1845), notable for its complex pose and the rendering of luxurious fabrics, and the two portraits of Madame Moitessier (one seated, 1856; one standing, 1851), which combine imposing presence with intricate detail and subtle classical allusions.

Ingres's portrait drawings, often executed more quickly and sometimes as preparatory studies, are considered by many to be among his freshest and most intimate works. Rendered with breathtaking delicacy and precision, they capture likeness and personality with an economy of means that highlights his absolute mastery of line. These drawings were highly sought after, particularly during his time in Italy when he needed to supplement his income. Whether in oil or graphite, Ingres approached portraiture with intense concentration, demanding long sittings from his subjects to achieve the perfection he sought.

Champion of History Painting

True to his academic convictions, Ingres dedicated much of his energy to grande peinture – large-scale history paintings based on classical, mythological, or religious themes. He believed these subjects offered the greatest scope for moral instruction and the display of artistic erudition, including complex compositions, knowledge of historical detail, and the idealized depiction of the human form.

The Apotheosis of Homer (1827), commissioned as a ceiling painting for the Louvre, is a grand statement of his artistic allegiances. It depicts the ancient poet being crowned, surrounded by legions of great artists and writers from antiquity to the 17th century, with Raphael and Poussin prominently featured. The composition is strictly symmetrical and hierarchical, a manifesto of Neoclassical order and reverence for the past.

Another major history painting was The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian (1834), commissioned for Autun Cathedral. This large, complex work, depicting an early Christian martyr urged on by his mother, received a mixed, even hostile, reception at the Salon. Critics found its composition crowded, its figures contorted, and its emotional pitch perhaps too intense, bordering on the dramatic effects Ingres usually decried in Romanticism. This setback deeply wounded Ingres and contributed to his decision to accept the directorship of the French Academy in Rome shortly thereafter. Other significant history paintings include the early Achilles Receiving the Ambassadors of Agamemnon (his Prix de Rome piece) and numerous works exploring themes from Greek mythology and Roman history.

The Odalisques, Orientalism, and Sensuous Line

Among Ingres's most famous and debated works are his depictions of odalisques (female harem slaves or concubines) and bathers, often set in vaguely Orientalist contexts. These paintings, particularly La Grande Odalisque (1814) and The Turkish Bath (1862), showcase a different facet of his art, one marked by sinuous lines, voluptuous forms, and a cool, detached eroticism.

La Grande Odalisque, commissioned by Napoleon's sister Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples, caused a scandal when first exhibited. Critics were baffled and outraged by the figure's anatomical distortions – her elongated back (famously said to possess three extra vertebrae), the serpentine curve of her limbs, the impossible twist of her neck. These were not errors, but deliberate aesthetic choices, sacrificing anatomical realism for the sake of a flowing, harmonious linear rhythm and an idealized, exotic sensuality. The inclusion of Oriental props like the hookah and turban placed the work within the burgeoning 19th-century fascination with the East, known as Orientalism.

Decades later, Ingres returned to similar themes in The Turkish Bath. Completed when he was over eighty, this complex, multi-figure composition, set within a circular tondo format, presents a dreamlike vision of languid female nudes in a steamy bathhouse. It distills a lifetime's preoccupation with the female form, classical prototypes (like the ancient Venus Kallipygos), and the power of line to convey sensuousness. While Ingres's Orientalism was generally more detached and idealized than the vibrant, often violent depictions by his rival Delacroix, these works reveal a fascination with the exotic and the erotic that complicates his image as a purely austere classicist. They also demonstrate his willingness to manipulate form in pursuit of abstract linear beauty, a quality that would later intrigue modern artists.

Ingres as Teacher and Academic Authority

Ingres exerted considerable influence not only through his paintings but also as a teacher and an authoritative figure within the French art establishment. After his triumphant return in 1824, he opened a successful studio, attracting numerous pupils. In 1829, he was appointed professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, and from 1835 to 1841, he served as Director of the French Academy in Rome, a prestigious post. Upon his return to Paris, he resumed his teaching and his role as the chief defender of academic orthodoxy.

His teaching methods emphasized the absolute necessity of drawing as the foundation of all art. "Drawing is the probity of art," is one of his most famous pronouncements. He encouraged meticulous study of classical sculpture and Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael. However, his pedagogical style was often perceived as dogmatic and rigid. He was known for his short temper and sharp tongue, and contemporary accounts suggest a demanding, sometimes tyrannical, presence in the classroom. He was accused of imposing his personal style on his students and stifling originality.

His position as the leader of the Neoclassical school inevitably placed him in direct opposition to Eugène Delacroix and the burgeoning Romantic movement. The rivalry between Ingres and Delacroix became legendary, symbolizing the fundamental aesthetic clash of the era: line versus color, order versus emotion, tradition versus innovation. Ingres vehemently condemned the Romantics' emphasis on painterly brushwork, dramatic subjects, and emotional expression, viewing it as a dangerous departure from sound principles. Despite his rigidity, he trained several notable artists, including Hippolyte Flandrin and Théodore Chassériau, although Chassériau later broke away, attempting to synthesize Ingres's line with Delacroix's color.

Later Years, Legacy, and Musical Pursuits

Ingres remained remarkably productive into his old age. Works like The Source (completed 1856, though begun decades earlier) and The Turkish Bath (1862) demonstrate his continued dedication and refinement of his lifelong themes. He continued to receive official honors and remained a revered, if somewhat feared, figure in the art world until his death in Paris in 1867 at the age of 86.

He bequeathed a vast collection of his works, including thousands of drawings, and his personal art collection to his hometown, forming the core of the Musée Ingres (now Musée Ingres Bourdelle) in Montauban. His legacy proved immense and multifaceted. While Neoclassicism as a dominant style faded after his death, his influence persisted. His emphasis on line profoundly impacted artists like Edgar Degas (evident in his ballet dancers and bathers) and later, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso during his classical phases. The formal purity and abstract qualities of his line appealed to artists seeking alternatives to Impressionism and later movements. Even Édouard Manet's Olympia, a cornerstone of modern art, can be seen as a provocative dialogue with the tradition of the reclining nude exemplified by Ingres's Grande Odalisque.

Beyond painting, Ingres maintained a lifelong passion for music. He was a skilled violinist, playing chamber music with friends. His musical talent was sufficiently recognized that the French phrase "violon d'Ingres" (Ingres's violin) came to mean a hobby or secondary passion pursued with dedication outside one's primary profession. He cultivated friendships with prominent musicians of the day, including Niccolò Paganini, Luigi Cherubini (whose portrait he painted), Charles Gounod, and Franz Liszt, whom he met and befriended in Rome in 1839. This connection to music underscores the importance of harmony, rhythm, and structure in his overall aesthetic sensibility.

Conclusion: A Complex Master

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres remains a pivotal figure in Western art history. As the principal heir to the Neoclassical tradition of Poussin and David, he championed the ideals of order, clarity, and the supremacy of line with unwavering conviction. His history paintings, though sometimes criticized even in his own time, represent a profound engagement with the classical past and academic principles. His portraits secured his contemporary fame and remain astonishing documents of psychological insight and technical brilliance. His controversial yet influential depictions of the female nude, particularly the odalisques, reveal a complex interplay of classicism, eroticism, and a willingness to distort anatomy in favor of abstract linear beauty.

A staunch defender of tradition and a fierce opponent of Romanticism, Ingres paradoxically laid groundwork for aspects of modernism through his emphasis on line and form. As a teacher, he shaped a generation of artists, even if his dogmatism sometimes provoked rebellion. His prolific output, technical mastery, and complex artistic personality ensure his continued relevance. Ingres was more than just a Neoclassicist; he was a master of line whose unique vision bridged the traditions of the past with the artistic explorations of the future.