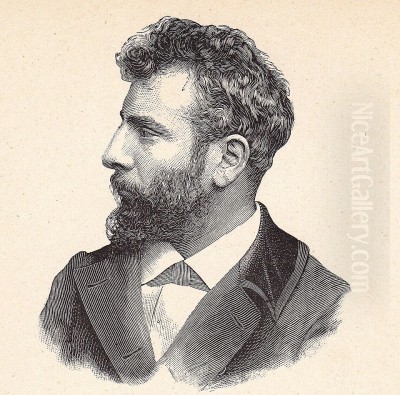

Henri Martin stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born in Toulouse in 1860 and passing away in 1943, his life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. While often categorized as a Post-Impressionist, Martin's work defies easy classification, weaving together threads of Symbolism, Neo-Impressionism, and a deeply personal connection to the landscapes of Southern France. He is particularly celebrated for his unique application of Pointillist techniques, not with the scientific rigor of some contemporaries, but with a poetic sensibility aimed at capturing the luminous effects of light and atmosphere. His prolific output includes easel paintings, intimate portraits, and monumental public murals, all marked by a distinctive sensitivity to color and a serene, often dreamlike quality.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Toulouse

Henri Jean Guillaume Martin was born in Toulouse, a major city in the Occitanie region of Southern France, on August 5, 1860. His background was modest; his father worked as a cabinet maker, while his mother brought an Italian heritage to the family. Initially, his father likely envisioned a more practical path for his son, but the young Henri harbored strong artistic aspirations. He demonstrated talent and determination, eventually persuading his father to allow him to pursue art as a career. This crucial support set him on a path that would define his life.

In 1877, at the age of seventeen, Martin enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts de Toulouse. This institution provided him with a solid foundation in academic drawing and painting techniques. His primary mentor during this period was Jules Garipuy. Garipuy himself was a respected artist who had trained in Paris and achieved success. Notably, Garipuy had been a student of the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, establishing a lineage, however indirect, connecting Martin to one of the giants of French art. Under Garipuy's tutelage, Martin honed his skills, absorbing the academic traditions while likely already beginning to explore his own artistic inclinations.

Parisian Studies and the Italian Influence

Martin's talent was evident early on. In 1879, his success at the Toulouse school earned him a scholarship, enabling him to move to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. This move was a pivotal moment, exposing him to a wider range of artistic currents and opportunities. In Paris, he sought further instruction and joined the studio of Jean-Paul Laurens. Laurens was a highly regarded figure in the academic art establishment, known for his large-scale historical and religious paintings. Studying with Laurens provided Martin with rigorous training and further exposure to the official art scene, including the influential Paris Salon.

Through his participation in the Paris Salon, Martin achieved recognition and secured another scholarship, this time for travel to Italy. This journey, undertaken in the early 1880s, proved profoundly influential on his artistic development. Immersed in the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, he studied the works of early masters like Giotto and Masaccio. The clarity, compositional strength, and emotional depth of their frescoes left a lasting impression. This Italian sojourn steered Martin away from purely academic concerns and towards a more poetic and evocative style. He began exploring Symbolist themes, creating works imbued with a sense of mystery, allegory, and dreamlike atmosphere, moving beyond straightforward representation.

The Turn Towards Neo-Impressionism and Pointillism

Upon returning to Paris, Henri Martin continued to exhibit at the Salon. While his early works showed Symbolist tendencies, his style underwent a significant evolution as he absorbed the innovations happening around him. He became increasingly interested in the scientific color theories and techniques being explored by the Neo-Impressionists, particularly the method known as Pointillism or Divisionism, pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. This technique involved applying small dots or strokes of pure color directly onto the canvas, relying on the viewer's eye to optically blend them, thereby achieving greater luminosity and vibrancy.

Martin adopted and adapted this technique to suit his own artistic temperament. Unlike the often more systematic and scientifically driven approach of Seurat, Martin's Pointillism was typically softer, less rigid, and more intuitive. He used divided brushstrokes – often short, comma-like marks rather than precise dots – to build up surfaces that shimmered with light and color. This method allowed him to capture the fleeting effects of sunlight on landscapes, water, and figures, creating a distinctive textured surface and a vibrant, atmospheric quality. His work Paolo Malatesta et Francesca da Rimini dans les nuages (often referred to as Francois de Rimini), exhibited at the Salon, brought him considerable attention and marked his growing reputation, showcasing this evolving style.

Gaining Recognition and Official Success

The late 1880s and 1890s marked a period of increasing success and recognition for Henri Martin. His participation in the Paris Salon became a regular feature, and his unique blend of Symbolist undertones with Neo-Impressionist technique garnered critical attention. A major milestone came in 1889 at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where he was awarded a Gold Medal for his painting Fête de la Fédération. This accolade significantly boosted his standing in the art world. Around this time, or shortly thereafter, he was also made a member of the Legion of Honour, France's highest order of merit, a testament to his growing stature.

His success was not confined to Salon exhibitions. In 1895, Martin held a highly successful solo exhibition at the prestigious Galerie Mancini in Paris. This show further cemented his reputation and demonstrated the appeal of his luminous, poetic style to collectors and critics. He was increasingly seen as a leading figure among the artists who were moving beyond Impressionism, exploring new ways to represent light, color, and emotion. His ability to secure both critical acclaim and official recognition set him apart.

The Muralist: Grand Decorations for Public Spaces

Beyond his easel paintings, Henri Martin became highly sought after for large-scale decorative mural projects. This aspect of his career highlights his connection to a tradition of public art, following in the footsteps of artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose own Symbolist murals were widely admired. Martin received several prestigious commissions to decorate important civic buildings, demonstrating the broad appeal and adaptability of his style to monumental formats.

One of his most significant commissions was for the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) in Paris, where he contributed decorative panels, including works for the Salle de l’Assemblée générale. He also received a major commission for the Capitole de Toulouse, the heart of his home city's government. Here, he created impressive murals, including the well-known Les Faucheurs (The Reapers), celebrating rural labor within the local landscape. Other important public commissions included decorations for the Palais de l'Élysée (the French President's official residence) and the Conseil d'État (Council of State). These large-scale works often depicted allegorical themes, scenes of local life, or idealized landscapes, executed in his characteristic divided brushstroke technique, filling vast spaces with light and color.

Marquayrol: A Sanctuary in the South

Despite his success in Paris and the demands of his public commissions, Henri Martin retained a deep connection to his native South of France. He was known to be somewhat introverted and found the hustle and bustle of Parisian life increasingly taxing. Around 1900, seeking tranquility and a closer connection to the landscapes that inspired him, Martin purchased a property called 'Marquayrol'. This estate was beautifully situated overlooking the village of Labastide-du-Vert in the Lot department, a region characterized by rolling hills, vineyards, and the winding Lot River valley.

Marquayrol became his primary residence and his artistic sanctuary for the rest of his life. He lived there with his wife, Marie-Charlotte Barbaroux, and their four sons. The serene environment provided endless inspiration. The gardens he cultivated, the sun-drenched hills, the village nestled below, the poplar trees lining the river – all became recurring motifs in his paintings. This move marked a shift in focus; while he continued to undertake commissions, his easel painting became almost exclusively dedicated to capturing the light, colors, and peaceful atmosphere of his immediate surroundings. The Marquayrol years represent the most harmonious and perhaps most personal phase of his artistic output.

Themes of Nature, Light, and Rural Life

The dominant theme throughout Henri Martin's mature work is the landscape, particularly the sunlit vistas of Southern France surrounding Marquayrol. He painted the changing seasons, the effects of light at different times of day, and the familiar landmarks of his adopted home. Works like The Landscape of Labastide-du-Vert (a title he used for multiple views) capture the essence of this region with warmth and sensitivity. His paintings often feature pathways winding through fields, stone bridges arching over streams, figures resting under trees (Shade, 1900), or the tranquil surfaces of ponds and rivers reflecting the sky.

Light was his central preoccupation. His Pointillist-inspired technique was perfectly suited to rendering the intense luminosity of the southern sun, the dappled light filtering through leaves, and the vibrant hues of the landscape. While rooted in observation, his paintings often possess a poetic, almost dreamlike quality, evoking a sense of timeless serenity (Dream in Autumn). He also frequently incorporated figures into his landscapes, often depicting scenes of rural life and labor, such as The Reapers (also the theme of his Capitole mural) or peasants working the land. These figures are typically integrated harmoniously into their surroundings, suggesting a deep connection between humanity and nature. His exploration of beauty (Beauty, 1900) often found expression in these idyllic garden and landscape scenes (Garden).

Portraits and Allegorical Echoes

While landscapes dominated his later output, Henri Martin also continued to explore other genres. He produced numerous portraits and self-portraits throughout his career. These works often display the same sensitivity to light and color as his landscapes, using divided brushstrokes to model form and capture the sitter's presence. His portraits often depict family members, friends, or local figures, rendered with warmth and intimacy. The setting, whether an interior or a garden at Marquayrol, frequently plays an important role, bathing the sitter in characteristic light.

Symbolist elements, though less overt than in his earlier Italian-influenced period, continued to surface occasionally in his work. Allegorical figures sometimes populate his landscapes, as seen in The Shepherd and the Three Muses (1900). Even his seemingly straightforward depictions of nature can carry symbolic weight, evoking themes of peace, harmony, labor, and the passage of time. His late triptych Memorial (1932), created for a public building in the nearby city of Cahors, likely blended landscape elements with commemorative or allegorical themes, demonstrating his continued engagement with works of public significance.

Relationships with Contemporary Artists

Henri Martin navigated the complex art world of his time, interacting with various artists and movements. His training connected him to the academic tradition through Jules Garipuy and Jean-Paul Laurens. His exploration of Neo-Impressionism placed him in dialogue with figures like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, although his application of their techniques remained distinct and personal. His mural work aligned him with the tradition of public decoration exemplified by Puvis de Chavannes.

He also formed significant personal friendships within the artistic community. A notable friendship developed with the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin, whom he met around the time of the 1900 Exposition Universelle, where both artists achieved great success. They shared mutual respect and likely found common ground in their dedication to their craft. Martin was also close friends with the painter Henri Le Sidaner, another artist known for his intimate and atmospheric depictions of light and landscape, often working in a related Post-Impressionist vein. Their shared sensibilities led some to refer to them as "brotherly geniuses." Later in life, he had some interaction with Fernand Léger, a key figure of Modernism, who even painted Martin's portrait, indicating respect across different artistic generations. These connections place Martin within a rich network of artists, from Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, whose focus on light paved the way, to fellow Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin who explored color and emotion, and Symbolists like Gustave Moreau.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Henri Martin spent the last four decades of his life primarily at Marquayrol, continuing to paint the landscapes he loved with undiminished passion. He remained active, exhibiting his work and maintaining his reputation as a respected figure in French art. He passed away at his beloved home in Labastide-du-Vert on November 12, 1943, during the difficult years of World War II.

His legacy resides in his unique synthesis of artistic currents. He successfully bridged the atmospheric concerns of Impressionism, the color theories of Neo-Impressionism, and the evocative mood of Symbolism. His adaptation of Pointillism, characterized by vibrant color and shimmering light, created a distinctive and highly appealing style. He excelled both in intimate easel paintings and monumental public decorations. His depictions of the Lot Valley remain iconic representations of that region, imbued with a sense of peace and timeless beauty. Today, his works are held in major museum collections across France, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, and numerous regional museums, as well as in collections worldwide, ensuring his contribution to French art continues to be appreciated.

Conclusion: A Painter of Light and Harmony

Henri Martin carved a unique path through the dynamic art world of fin-de-siècle France. He absorbed the lessons of academic training, the revelations of Italian masters, the innovations of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, and the introspective spirit of Symbolism, forging a style that was entirely his own. His paintings, whether intimate views of his garden at Marquayrol or grand murals for public spaces, are consistently characterized by their luminous color, sensitivity to light, and an underlying sense of harmony and tranquility. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Martin created a body of work that celebrates the beauty of the natural world and the quiet dignity of rural life with enduring appeal, securing his place as a master of light and poetic observation in French Post-Impressionist painting.