Henri-Pierre Danloux stands as a significant figure in French art history, a painter whose career bridged the tumultuous final decades of the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic era. Born in Paris in 1753, he navigated the complex political and artistic currents of his time, achieving renown primarily as a portraitist, though he also engaged with history painting. His life and work reflect both the continuity of French artistic traditions and the profound impact of exile and cross-cultural exchange, particularly with Great Britain. Danloux's elegant and sensitive style earned him patronage among the aristocracy on both sides of the Channel, leaving behind a legacy of insightful portraits that capture the personalities and fashions of a transformative period. He passed away in Paris in 1809, his work serving as a testament to a life spent mastering the art of representation amidst historical upheaval.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Henri-Pierre Danloux's journey into the world of art began in Paris, the epicentre of French culture. Orphaned at a young age, he was raised by an uncle, suggesting a need for resilience and self-reliance early in life. His formal artistic education commenced under the guidance of Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié, a painter known for his genre scenes and later historical subjects. This initial training would have grounded Danloux in the technical fundamentals of painting prevalent in mid-18th century France.

Seeking further refinement and exposure to the dominant trends, Danloux subsequently entered the studio of Joseph-Marie Vien around 1773. Vien was a pivotal figure in the nascent Neoclassical movement, advocating a return to the clarity, order, and moral seriousness inspired by classical antiquity, reacting against the perceived frivolity of the Rococo style. Studying under Vien provided Danloux with a direct link to the forefront of artistic innovation and academic respectability. Vien's influence, particularly his emphasis on drawing and composition, would shape Danloux's approach throughout his career.

A crucial step in his development came in 1775 when Vien was appointed Director of the French Academy in Rome. Danloux accompanied his master to the Eternal City, embarking on an extended period of study in Italy that was considered essential for any ambitious artist of the era. This immersion in the art of the Italian masters, both Renaissance and Baroque, as well as the direct encounter with classical ruins, profoundly impacted his artistic vision.

During his time in Italy, Danloux did not confine himself to Rome. He travelled extensively, absorbing the diverse artistic atmospheres of Naples, Padua, Florence, and Venice. Each city offered unique lessons: the dramatic realism of Caravaggio's followers in Naples, the Renaissance grace of Florence, the rich colour and light of the Venetian school. This Italian sojourn broadened his technical skills and aesthetic sensibilities, equipping him with a versatile artistic vocabulary upon his return to France.

Rise to Prominence in France

Returning to France in 1783, Danloux chose not to settle immediately in the competitive artistic hub of Paris, but rather established himself in Lyon. This strategic move allowed him to build a reputation in a major provincial centre. In Lyon, he quickly gained recognition as a talented portrait painter, attracting commissions from the local elite. His ability to capture a likeness with sensitivity and elegance resonated with clients seeking refined representations of themselves and their families.

During this period, Danloux's style often drew comparisons to that of Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Greuze was immensely popular for his sentimental genre scenes and expressive portraits, particularly those of women and children, characterized by soft modelling and emotive gazes. Danloux adopted elements of this fashionable style, appealing to the tastes of the French aristocracy who appreciated the blend of naturalism and delicate sensibility found in Greuze's work. This alignment with prevailing tastes helped solidify his standing and secure important commissions.

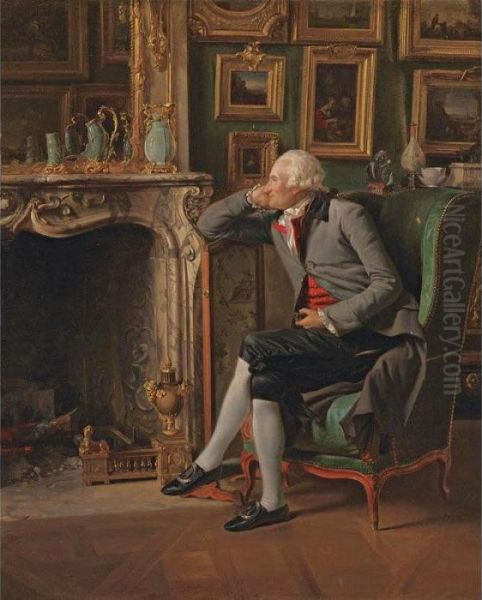

His success was not limited to Lyon. His growing reputation brought him into contact with influential figures closer to the court. Among his notable patrons during the pre-Revolutionary years was the Baron de Besenval, a Swiss-born courtier and military officer known for his sophisticated tastes and art collection. Danloux painted Besenval on multiple occasions, including a famous portrait depicting the Baron in his salon, surrounded by his prized collection of Chinese porcelain – a testament to the era's fascination with Chinoiserie and the artist's skill in rendering luxurious interiors and personal attributes.

These commissions from figures like Besenval indicate Danloux's successful integration into the upper echelons of French society before the Revolution. His portraits from this era often display a refined elegance, careful attention to costume and setting, and a psychological acuity that captured the sitter's personality, solidifying his reputation as a sought-after portraitist within the Ancien Régime. He was also commissioned to paint members of the royal family, including potentially Marie Antoinette, though the revolutionary turmoil likely interrupted or prevented the completion of such high-profile projects.

The Tumult of Revolution and Exile

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 dramatically altered the course of Danloux's life and career. As an artist who had found favour with the aristocracy and held royalist sympathies, the increasingly radical political climate posed a significant threat. The dismantling of the old social order, the persecution of nobles and royalists, and the general instability made it dangerous for individuals associated with the Ancien Régime to remain in France.

In 1792, as the Revolution intensified with the overthrow of the monarchy and the beginning of the Reign of Terror, Danloux made the difficult decision to leave his homeland. He sought refuge in London, joining a growing community of French émigrés who had fled the violence and uncertainty. This move marked the beginning of a decade-long exile in Great Britain, a period that would profoundly influence his artistic development and expose him to a different cultural and artistic milieu.

Life as an émigré presented both challenges and opportunities. While separated from his established network of patrons in France, London offered a vibrant art scene and a wealthy aristocracy eager for sophisticated portraiture. Danloux had to adapt to new tastes and compete with established British artists, but his French training and elegant style provided a distinct appeal. His exile, forced by political circumstances, paradoxically opened a new chapter in his artistic journey.

Success and Adaptation in Britain

Upon arriving in London, Henri-Pierre Danloux set about establishing himself within the competitive British art market. He leveraged his skills and French cachet, quickly finding patronage among the British nobility and fellow émigrés. His presence was formally announced to the London art world when he began exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in 1793. This platform allowed him to showcase his talents to a wider audience and attract significant commissions.

During his ten years in Britain, Danloux's style underwent a noticeable evolution, absorbing influences from the leading British portraitists of the day. He particularly admired the work of Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose dynamic compositions, fluid brushwork, and glamorous portrayal of sitters were highly fashionable. The influence of Lawrence can be seen in the increased elegance and perhaps a touch more bravura in Danloux's British-period works.

He also engaged with the styles of other prominent figures like John Hoppner and George Romney. Hoppner, like Lawrence, was a favoured portraitist of the aristocracy, known for his rich colour and flattering likenesses. Romney, though slightly earlier, had established a reputation for graceful, often more intimate portraits, particularly of women and children. Exposure to these artists encouraged Danloux to refine his technique and adapt his palette and compositional strategies to suit British tastes, moving towards a smoother finish and often more elaborate settings than in some of his earlier French works.

His adaptability and skill earned him numerous commissions from prominent British figures. One notable example is his portrait of Admiral Adam Duncan, the victor of the Battle of Camperdown. Painting such national heroes demonstrated Danloux's successful integration into British society and his ability to capture the dignity and authority expected in portraits of high-ranking individuals. He also continued to paint French émigrés, providing a visual record of this displaced community. His London studio became a point of contact between French and British society.

Despite his success, his work sometimes faced criticism. Some contemporary observers felt his style, while elegant, could appear somewhat "frozen" or lacking the dynamic innovation seen in the best of his British rivals. This critique highlights the differing aesthetic expectations between the French and British traditions, with the British perhaps favouring a greater sense of immediacy and painterly freedom at the time. Nonetheless, Danloux carved out a successful niche, appreciated for his refinement, sensitivity, and the distinctly Continental elegance he brought to British portraiture.

Artistic Style and Technique

Henri-Pierre Danloux's artistic style is best characterized by its elegance, refinement, and psychological sensitivity. Throughout his career, whether working in France or Britain, he demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the subtle nuances of his sitter's personality and social standing. His approach combined the meticulousness of his French academic training with a responsiveness to the evolving tastes of his clientele and the influence of his contemporaries.

Early in his career, the influence of Greuze was apparent in the soft modelling, delicate rendering of fabrics, and the often sentimental or intimate mood of his portraits. He excelled at depicting the textures of silk, lace, and powdered hair, details highly valued by his aristocratic patrons. His use of colour was typically harmonious and controlled, favouring subtle gradations and a generally light palette, although he could employ richer tones for dramatic effect, particularly in male portraits or history paintings.

His mastery of light and shadow was crucial to his technique. He often used gentle, directional lighting to model faces and figures, creating a sense of volume and presence without harsh contrasts. This careful handling of chiaroscuro contributed to the overall sense of refinement and composure that permeates his work. His compositions were generally well-balanced, often employing traditional formats but adapted with a certain grace and naturalness in the sitter's pose and expression.

The decade spent in London introduced new elements into his style. Exposure to Lawrence, Hoppner, and Romney encouraged a slightly more fluid brushstroke at times and an enhanced sense of fashionable elegance, particularly in the depiction of drapery and backgrounds. While retaining his characteristic precision, his British portraits occasionally display a greater dynamism or a more overtly sophisticated air, reflecting the tastes of London society.

Danloux was particularly adept at capturing the innocence and charm of children, a skill likely honed through his affinity with the work of Greuze. His portraits of family groups or individual children are often imbued with a tender intimacy. Across his oeuvre, his draughtsmanship remained strong, providing a solid foundation for his painterly execution. He sought to convey the "essence" and emotional state of the sitter, moving beyond mere surface representation to offer a glimpse into their inner life, a quality that ensured his enduring appeal.

Representative Works

Danloux's oeuvre includes numerous portraits that exemplify his skill and stylistic range. Several key works stand out:

_Portrait of Charles X as Comte d'Artois_: This portrait of the future King of France, likely painted during Danloux's pre-exile period or possibly later, showcases his ability to depict royalty with the requisite dignity and elegance. Such works cemented his reputation among the highest circles. A version is held in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, likely painted during the Comte's own exile.

_Portrait of Jacques Delille and his Wife_: Jacques Delille was a celebrated poet and translator, famous for his work on Virgil. Portraying such a prominent literary figure indicates Danloux's engagement with the cultural elite. The double portrait, now in the Palace of Versailles, likely highlights the intellectual and domestic harmony of the couple, rendered with Danloux's characteristic sensitivity.

_Portrait of Jean-Louis Gustave d'Hautefort and His Sister_: This charming double portrait captures the youthful innocence and aristocratic bearing of the siblings. It demonstrates Danloux's skill in composing multi-figure portraits and his delicate handling of young sitters, reflecting the influence of Greuze while maintaining a distinct elegance.

_Baron de Besenval in his Salon de Compagnie_: Mentioned earlier, this work is significant not only as a portrait of an important patron but also for its detailed depiction of an interior and a collection of Chinese porcelain. It speaks to the sitter's worldliness and taste, and Danloux's ability to create a rich contextual setting. It serves as an excellent example of his pre-Revolutionary French style.

_Constantia Foster and Her Nephew_: This portrait, likely from his British period, shows his continued engagement with themes of family and youth. It probably displays the smoother finish and refined elegance characteristic of his London work, adapted to British sensibilities while retaining his French grace.

_Portrait of Henry John Lambert_: Representing his work for British patrons, this portrait would likely conform to the expectations of London society, balancing likeness with fashionable presentation. Portraits like this were essential for maintaining his practice during his exile.

_Portrait of Admiral Adam Duncan_: A significant commission during his British exile, this work would have required Danloux to convey authority and national pride, showcasing his versatility in adapting to different types of sitters and commemorative purposes.

These works, housed in major collections like Versailles, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and others, illustrate the consistent quality and adaptability of Danloux's art across different phases of his career and geographical locations.

Connections and Contemporaries

Henri-Pierre Danloux's artistic journey was shaped by his interactions with numerous other artists, either as teachers, influences, or peers. Understanding these connections helps place his work within the broader context of late 18th and early 19th-century European art.

His foundational training came from Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié and, more significantly, Joseph-Marie Vien. Vien, a key proponent of Neoclassicism, not only taught Danloux but also facilitated his crucial study trip to Rome. Vien's other famous students included Jacques-Louis David, the leading figure of Neoclassicism, placing Danloux within an important pedagogical lineage, even if his own style leaned more towards portraiture than David's rigorous history painting.

In France, the stylistic influence of Jean-Baptiste Greuze was paramount, particularly on Danloux's early portraiture and his depictions of children, known for their sentimental appeal and delicate execution. He also would have been aware of, and likely had exchanges with, other prominent French artists of the time, such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose Rococo exuberance represented a contrasting artistic current, and perhaps figures associated with landscape or genre painting like Jean-François Millet (though the snippet likely refers to an earlier Millet or a different artist, as the famous Barbizon painter was later).

His exile in London brought him into the orbit of the leading British portraitists. He clearly absorbed lessons from Sir Thomas Lawrence, John Hoppner, and George Romney. While the snippets suggest influence rather than direct collaboration, Danloux operated within the same competitive market, exhibiting alongside them at the Royal Academy and vying for similar patrons. His style adapted in response to their success and the prevailing British taste they exemplified.

A fascinating point of connection involves Sir Henry Raeburn, the leading Scottish portraitist. The attribution debate concerning the iconic painting The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch (commonly known as The Skater), traditionally assigned to Raeburn, saw Danloux proposed as a possible author in 2005. While this remains highly contested and largely unaccepted, the mere suggestion highlights perceived stylistic affinities, particularly in the elegant fluidity and Continental sensibility that some critics saw in the work, potentially linking the two artists, albeit controversially.

Danloux also had relationships with his sitters that sometimes blurred the lines, as seen with Anne Guéret. Described as a student for whom he held deep affection and painted multiple portraits, this connection points to the personal dynamics that could exist within the studio environment. Similarly, his portraits of patrons like the Baron de Besenval or Jean-Louis Gustave d'Hautefort represent collaborations of a sort, requiring interaction and understanding between artist and sitter. These connections underscore the social dimension of portrait painting.

Anecdotes and Controversies

Several incidents and debates add layers of intrigue to Henri-Pierre Danloux's biography and artistic legacy. These episodes reveal the complexities of attribution, the impact of political turmoil, contemporary criticism, and the personal dimensions of his life and work.

Perhaps the most widely discussed controversy involving Danloux is the aforementioned attribution debate surrounding The Skater. In 2005, a curator at the National Gallery of Scotland proposed that this beloved painting, long considered a masterpiece by Sir Henry Raeburn, might actually be by Danloux. The argument rested on stylistic analysis, suggesting the painting's fluid elegance and composition were more akin to French sensibilities, potentially Danloux's, than Raeburn's typically more robust style. This suggestion sparked considerable debate among art historians, with many defending the traditional attribution to Raeburn. While the claim remains largely unsubstantiated and unproven, it momentarily thrust Danloux into the spotlight in relation to one of Britain's most famous paintings.

Danloux's close ties to the French aristocracy and potentially the royal family, including rumoured commissions from Marie Antoinette, placed him in a precarious position during the Revolution. His subsequent flight to England underscores the real dangers faced by artists associated with the old regime. This period highlights the profound impact political events could have on an artist's life, forcing exile and adaptation to new environments.

While successful in London, Danloux was not immune to criticism. Some British commentators found his style, though elegant, perhaps too polished or lacking in vigour compared to homegrown talents like Lawrence. Descriptions of his work as occasionally "frozen" suggest a perception that his refinement sometimes came at the expense of spontaneity or deep character insight, reflecting differing national aesthetic preferences.

His incorporation of Orientalist elements, such as the detailed depiction of Chinese porcelain in the portrait of Baron de Besenval, reflects a broader 18th-century European fascination with Chinoiserie. While appreciated by patrons like Besenval who wished to showcase their collections and cosmopolitan taste, from a modern perspective, such depictions can sometimes enter discussions about cultural representation and the exoticization of non-European cultures prevalent in the era.

Finally, the personal dimension of his relationship with his student Anne Guéret, marked by deep affection and multiple portraits, attracted attention. While perhaps not scandalous, it points to the intimate dynamics often present in the artist-student or artist-model relationship, adding a layer of personal narrative to his professional life and suggesting how emotional connections could find expression in his art.

Return to Paris and Later Years

Following the stabilization of France under Napoleon Bonaparte and the signing of the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 (though he returned slightly earlier, in 1801, likely facilitated by changing political conditions allowing émigrés to return), Henri-Pierre Danloux ended his decade-long exile in London and returned to Paris. He re-entered a transformed artistic landscape, one now dominated by the Neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David and his school, and increasingly shaped by the patronage demands of the Napoleonic regime.

Danloux resumed his career in Paris, continuing to work as a portraitist and occasionally undertaking historical subjects. He exhibited his works at the Paris Salon, the premier venue for artists to display their creations and gain official recognition. His paintings were generally well-received, demonstrating that his elegant style, honed by years of experience in both France and Britain, still held appeal.

He likely sought patronage from the new elite of the Consulate and later the Empire, adapting his skills to portray the figures of this new era. While the provided snippets mention commissions from French royalty (likely referring to the pre-Revolutionary period or perhaps later Bourbon restoration figures after his death), his activity between 1801 and his death in 1809 would have involved navigating the patronage structures of Napoleonic France. His experience painting nobility and military figures in Britain would have served him well in this context.

His later French works likely continued to display the refined technique and psychological insight that were hallmarks of his style, perhaps reintegrating elements of French taste while retaining the polish acquired during his London years. He remained active until his death in Paris in 1809, leaving behind a substantial body of work created over a career that spanned significant historical and artistic transitions.

Legacy and Conclusion

Henri-Pierre Danloux occupies a unique position in late 18th and early 19th-century art history. Primarily celebrated as a portraitist, his career is notable for its international dimension, particularly his successful navigation of the distinct art worlds of pre-Revolutionary France, émigré London, and Napoleonic Paris. His work serves as a bridge between the French and British portrait traditions of the era, showcasing an ability to adapt and synthesize influences while maintaining a signature elegance.

His artistic legacy rests on his refined style, characterized by sensitive modelling, harmonious colour, meticulous attention to detail, and an ability to capture the personality of his sitters with grace and psychological depth. Influenced initially by the French tradition, particularly the sensibility of Greuze, his work gained an added layer of sophistication and polish through his engagement with British masters like Lawrence during his decade of exile.

Danloux provides a fascinating case study of an artist whose life was directly shaped by the French Revolution. His forced exile led to a significant period of artistic development in Britain, enriching his style and broadening his reputation. He successfully catered to aristocratic tastes on both sides of the Channel, leaving behind a valuable visual record of the elite society of his time.

While perhaps overshadowed in grand narratives by more revolutionary figures like David, Danloux's contribution lies in the consistent quality and enduring appeal of his portraiture. His ability to convey elegance, intimacy, and individual character ensures his works remain engaging. He navigated turbulent times with artistic skill and adaptability, leaving a rich heritage of paintings that reflect both the specificities of his era and the timeless art of capturing the human likeness. His career demonstrates the complex interplay of artistic training, personal circumstance, political events, and cross-cultural exchange in shaping a significant artistic identity.