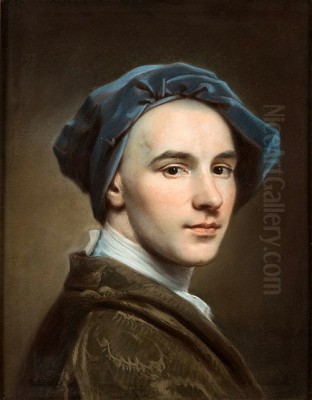

William Hoare, often distinguished as "Hoare of Bath," stands as a significant figure in the annals of eighteenth-century British art. A founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Hoare was a preeminent portraitist, particularly celebrated for his mastery of pastels, a medium he helped popularize in England. His career, flourishing in the fashionable spa town of Bath, captured the likenesses of the era's elite, leaving behind a rich visual record of Georgian society. His journey from a Suffolk upbringing to the studios of Rome and finally to the pinnacle of Bath's artistic scene is a testament to his talent, adaptability, and astute understanding of his clientele.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

William Hoare was born in Eye, Suffolk, around 1707 (some sources suggest 1706). His father was reportedly a farmer, and details about his mother remain obscure. This rural beginning provided a stark contrast to the sophisticated world of art he would later inhabit. His early education took place at Faringdon School in Berkshire, after which his artistic inclinations became apparent, leading him to London to pursue formal training.

In the bustling metropolis, Hoare was apprenticed to Giuseppe Grisoni, an Italian painter who had settled in London. Grisoni, known for his decorative work and portraits, provided Hoare with a foundational understanding of Italian artistic principles. This tutelage was pivotal, as it not only honed Hoare's technical skills but also ignited his desire to experience Italian art firsthand. The allure of Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and Baroque, was irresistible for aspiring artists of the period.

The Italian Sojourn: A Crucible of Learning

Around 1728, William Hoare embarked on the quintessential artistic pilgrimage of his time: the Grand Tour, accompanying his master Grisoni to Italy. This period, extending for nearly a decade, was transformative. He immersed himself in the artistic treasures of Florence and, more significantly, Rome. In Rome, the young Hoare diligently studied the works of the Old Masters, a common practice for artists seeking to refine their technique and absorb the classical aesthetic. He supported himself by producing copies of these masterpieces, a testament to his growing skill and a common means of income for artists abroad.

During his Roman years, Hoare sought instruction from several notable figures. He is known to have studied with Francesco Imperiali, a respected painter of historical and allegorical subjects. More crucially, he came under the influence of Pompeo Batoni, who would become one of Rome's leading painters, particularly renowned for his Grand Tour portraits of British aristocrats. Batoni's elegant style and ability to capture a sitter's character undoubtedly left an impression on Hoare. He also reportedly associated with the sculptor Peter Scheemakers and another artist known as De Vau. Some accounts also mention Francesco Colman as one of his teachers or associates during this formative period.

It was also in Italy that Hoare likely developed his proficiency in pastels, or "crayons" as they were often called. The Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera had elevated pastel portraiture to an art form of international acclaim, and her delicate, flattering likenesses were highly sought after. Hoare's subsequent success with pastels suggests he was keenly aware of Carriera's work and the medium's potential for capturing subtle expressions and textures with a unique softness and immediacy. His time in Italy was not solely about formal study; he also formed connections with fellow artists, including the Scottish painter Allan Ramsay and the Swedish sculptor Tobias Sergel, fostering a network that would be valuable throughout his career.

Return to England and the Rise of "Hoare of Bath"

William Hoare returned to England around 1737 or 1738. He initially attempted to establish himself in London, the primary center of artistic patronage. However, the London art scene was competitive, with established figures dominating the market. Finding limited success as a painter of historical subjects, a genre he might have aspired to following his Italian studies, Hoare wisely adapted his focus.

He made the strategic decision to move to Bath in Somerset. In the mid-eighteenth century, Bath was a burgeoning spa town, a fashionable resort for the wealthy and aristocratic seeking health cures and social amusement. This seasonal influx of affluent visitors created a fertile market for portrait painters. Hoare quickly established himself as the leading portraitist in the town, earning the moniker "Hoare of Bath." His studio became a popular destination for those wishing to have their likenesses captured, a memento of their time in the stylish resort.

His success in Bath was built on his ability to produce elegant and sympathetic portraits that appealed to the tastes of his clientele. He worked proficiently in both oil and pastel, offering patrons a choice of medium. His pastel portraits, in particular, were admired for their delicacy, speed of execution, and the fresh, vibrant likenesses they conveyed. He became known for his directness and his insightful ability to capture the personality of his sitters, qualities that resonated with the Georgian sensibility.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

William Hoare's artistic style is characterized by its elegance, sensitivity, and a certain Rococo grace, particularly evident in his pastel work. His Italian training provided him with a solid grounding in draughtsmanship and composition, while his exposure to artists like Pompeo Batoni and the pervasive influence of Rosalba Carriera shaped his approach to portraiture.

In his oil paintings, Hoare demonstrated a competent and often insightful approach. His portraits are typically well-composed, with attention paid to the rendering of fabrics and accessories that denoted the sitter's status. While perhaps not possessing the dazzling brushwork of a Thomas Gainsborough or the grand manner of a Sir Joshua Reynolds, Hoare's oils are distinguished by their honest portrayal and a quiet dignity. He often employed a warm palette and a smooth finish, creating likenesses that were both pleasing and accurate.

It was in the medium of pastels, however, that Hoare truly excelled and made a distinctive contribution to British art. He was one of the first British-born artists to achieve widespread acclaim for his pastel portraits. This medium, consisting of pure powdered pigment bound into sticks, allowed for a directness and speed of application that could capture fleeting expressions and a sense of immediacy. Hoare's pastels are notable for their soft, blended tones, delicate handling of features, and the luminous quality he achieved in rendering skin tones. He skillfully exploited the medium's capacity for both linear definition and painterly effects. His understanding of light and shadow, honed through his Italian studies, translated effectively into the nuanced gradations possible with pastels.

The influence of French Rococo artists, such as Maurice Quentin de La Tour or Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, who were masters of pastel, can also be discerned in the charm and intimacy of Hoare's work in this medium. A trip to France and the Netherlands in 1749 may have further exposed him to continental trends, although some contemporaries reportedly criticized a perceived "French style" in his work thereafter, suggesting a tension between native British tastes and foreign influences.

Hoare's ability to capture a sitter's character with "directness and sympathy" was a hallmark of his style. He avoided excessive flattery but managed to present his subjects in a favorable and engaging light, a crucial skill for a successful portraitist reliant on the satisfaction of his patrons.

Prominent Patrons and Notable Sitters

Hoare's success in Bath brought him a distinguished clientele. He painted many of the leading figures of the day who frequented the spa town. Among his most important patrons was Henry Pelham-Clinton, the 2nd Duke of Newcastle, and his family. Hoare produced numerous portraits for the Newcastle family, solidifying his reputation among the aristocracy.

Another significant sitter was William Pitt the Elder, later 1st Earl of Chatham, one of Britain's most influential statesmen. Hoare painted Pitt on several occasions, and these portraits are considered among his finest works, capturing the statesman's commanding presence and intellectual vigor. These commissions not only provided financial reward but also enhanced Hoare's social standing and visibility.

His sitters also included prominent members of Bath society, such as Ralph Allen, the postal reformer and quarry owner who was instrumental in Bath's development, and Dr. William Oliver, inventor of the Bath Oliver biscuit and a key figure at the Bath Mineral Water Hospital. Hoare's involvement with the hospital extended beyond simply painting its benefactors; he was actively involved in its operations, serving as a governor, which further integrated him into the fabric of Bath's civic and social life.

Other notable figures who sat for Hoare include Christopher Anstey, author of the popular satirical poem "The New Bath Guide," and Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple, a prominent politician. The breadth of his clientele, from dukes and statesmen to local dignitaries and literary figures, underscores his central role in Bath's artistic and social milieu.

Representative Works

William Hoare's oeuvre is rich with portraits that exemplify his skill in both oil and pastel. Among his most celebrated works is the pastel series known as "The Four Seasons." These allegorical depictions, likely representing idealized female figures or perhaps specific sitters in symbolic guise, showcase his mastery of the pastel medium, with their delicate coloration and graceful compositions. These works demonstrate his ambition to move beyond straightforward likenesses into more imaginative realms.

Another significant work often cited is "Venus and Diana," though details about this specific piece can be varied. If it refers to a mythological subject, it would highlight his classical training and aspirations beyond portraiture. However, much of his fame rests securely on his portraits.

His portraits of William Pitt the Elder are particularly noteworthy. One iconic image depicts Pitt in his parliamentary robes, exuding authority and intelligence. These works were widely reproduced as engravings, disseminating Hoare's imagery to a broader public and cementing Pitt's public persona. The portrait of the "Second Duke of Newcastle's Son" (likely referring to one of the Duke's children) would be representative of his work for aristocratic families, characterized by a blend of formality and youthful charm.

Hoare also undertook religious commissions, including paintings for St Michael's Church in Bath and the Octagon Chapel. These works, though less numerous than his portraits, demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with the broader artistic demands of his community. His contributions to the Bath Mineral Water Hospital also included portraits of its founders and benefactors, which served as both commemorations and encouragements for further philanthropy. Many of his works are now held in public collections, including the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and various regional museums, as well as in private collections, particularly those of the descendants of his sitters.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and the Royal Academy

William Hoare practiced his art during a vibrant period in British art history, alongside many distinguished contemporaries. In Rome, he had encountered Allan Ramsay, who would become a principal rival to Sir Joshua Reynolds in London. He also knew Pompeo Batoni, who, while Italian, was a key figure for British Grand Tourists. Later in his career, Hoare was part of a circle that included the Swiss-born artist Henry Fuseli, known for his dramatic and often unsettling Romantic paintings. Hoare's friendships extended to artists like William Pars and Alexander Day, whom he also knew from his Italian days.

Upon his return to England and establishment in Bath, Hoare initially faced little direct competition. However, the arrival of Thomas Gainsborough in Bath in 1759 presented a significant new artistic force. Gainsborough, with his fluid brushwork and naturalistic sensibility, quickly gained popularity. While they were, in a sense, rivals for commissions, the relationship appears to have been largely amicable. Both artists catered to the fashionable clientele of Bath, and their distinct styles offered patrons a choice.

William Hoare was a key figure in the professionalization of art in Britain. He was one of the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, an institution established under the patronage of King George III to raise the status of art and artists in Britain. His inclusion among the initial thirty-six members, alongside luminaries like Sir Joshua Reynolds (its first President), Thomas Gainsborough, Benjamin West, Angelica Kauffman, and Mary Moser, underscores his high standing within the artistic community. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from its inception until 1779, primarily showing portraits.

His involvement with the Society of Artists of Great Britain, a precursor to the Royal Academy, also highlights his commitment to advancing the cause of British artists. These institutional affiliations provided platforms for exhibition, discussion, and the education of future generations of artists.

Family, Personal Life, and Other Interests

William Hoare married a Miss Coulthurst, with whom he had several children. His family life seems to have been stable and supportive of artistic pursuits. Two of his children followed him into the arts. His son, Prince Hoare (1755-1834), became a noted painter, primarily of historical subjects, and also a successful dramatist and writer on art. Prince Hoare studied under his father and later under Anton Raphael Mengs in Rome, and he maintained a close and friendly relationship with his father throughout his life. He would later write "An Inquiry into the Requisite Cultivation and Present State of the Arts of Design in England" (1806).

Hoare's daughter, Mary Hoare (1744-1820), also became an accomplished artist, exhibiting paintings at the Royal Academy. She married fellow artist Henry Singleton, though this marriage was later annulled. Mary Hoare's success as a professional artist was notable for a woman in the eighteenth century, and her father's encouragement was likely instrumental.

The provided source material mentions William Hoare's connection to the C. Hoare & Co. bank, suggesting he was a partner and that his wealth derived more from banking than art, and that he possessed strict business ethics and a keen market judgment, though sometimes perceived as having a severe personality. This connection to the Hoare banking family is plausible, as the artist was related to this prominent dynasty (Sir Richard Hoare, founder of the bank, was his great-uncle). This familial connection would have provided financial stability and valuable social networks. However, his primary public identity and historical significance stem from his artistic career. His involvement with the Bath Mineral Water Hospital as a governor also indicates a commitment to civic duty and an engagement with the community beyond his artistic practice.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

William Hoare continued to paint actively throughout much of his life, though his exhibition activity at the Royal Academy ceased after 1779. He remained a respected figure in Bath, having shaped the town's artistic landscape for several decades. His influence extended through his students, including his own children, and through the example he set as a successful provincial portraitist who also engaged with the national art scene via the Royal Academy.

He passed away in Bath on December 12, 1792, at the age of 85, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant reputation. He was buried in St. Swithin's Church, Walcot, Bath.

In art historical terms, William Hoare is recognized as one of the most important portrait painters in Britain during the mid-eighteenth century, particularly outside London. He holds a special place as a pioneer and master of pastel portraiture in England, a medium that perfectly suited the era's taste for elegance and intimacy. Artists like John Russell and Daniel Gardner would later build upon the tradition of pastel painting that Hoare helped to establish.

His portraits provide an invaluable visual record of Georgian society, capturing the likenesses of statesmen, aristocrats, intellectuals, and the fashionable figures who flocked to Bath. His works are characterized by their sensitivity, technical skill, and an ability to convey the sitter's personality. While perhaps overshadowed in popular imagination by contemporaries like Reynolds or Gainsborough, Hoare's contribution to British art is undeniable. He successfully navigated the art markets of Rome and Bath, adapted his style to suit his clientele, and played a role in the institutional development of art in Britain. His dedication to his craft and his prolific output ensure his place as a distinguished artist of his time, "Hoare of Bath," a name synonymous with the refined portraiture of the Georgian age.

Conclusion

William Hoare's career exemplifies the opportunities and challenges faced by artists in eighteenth-century Britain. From his early training and transformative Italian studies to his establishment as Bath's premier portraitist, he demonstrated talent, adaptability, and a keen understanding of his patrons' desires. His mastery of pastels brought a fresh vibrancy to British portraiture, and his oil paintings captured the dignity and character of his sitters with understated elegance. As a founding member of the Royal Academy, he contributed to the growing prestige of British art. His legacy endures not only in the numerous portraits that grace public and private collections but also in his role as a key figure in the cultural life of Bath and a significant contributor to the rich tapestry of Georgian art. His ability to capture the essence of an era, its people, and its aspirations, secures his lasting importance in the history of British art.