Henry Somm, born François Clément Sommier (1844-1907), stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the vibrant Parisian art world of the late nineteenth century. Active during a period of profound artistic transition, Somm navigated the currents of Impressionism, Symbolism, and the burgeoning craze for Japanese art known as Japonisme. While perhaps less universally recognized today than some of his contemporaries, Somm was a highly skilled and respected artist, particularly admired for his delicate etchings, witty illustrations, and elegant watercolors capturing the spirit of his time. His work provides a unique window into the aesthetic sensibilities and social milieu of Belle Époque Paris, marked by a distinctive blend of keen observation, decorative flair, and a deep engagement with Japanese aesthetics.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

François Clément Sommier was born in Rouen, Normandy, in 1844. His initial artistic training took place in his hometown at the École Municipale des Beaux-arts. Like many ambitious young artists of his generation, he was drawn to the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. He arrived in the capital around 1867, seeking to further his education and establish his career.

In Paris, Somm enrolled in the studio of Isidore Pils (1813-1875). Pils was a respected academic painter, known primarily for his historical and military scenes, often executed on a grand scale. While Pils's traditional approach might seem distant from Somm's later, more intimate and modern style, studying within the academic system provided Somm with a solid foundation in drawing and composition, skills that would underpin his later work across various media. The Paris Somm entered was a city undergoing rapid transformation, both physically under Haussmann's renovations and culturally, with new artistic ideas challenging established norms.

The Embrace of Japonisme

One of the most defining aspects of Henry Somm's artistic identity was his early and passionate engagement with Japonisme. The arrival of Japanese prints, ceramics, textiles, and other decorative objects in Europe following the reopening of Japan to the West in the 1850s had a revolutionary impact on Western art. Artists were captivated by the novel compositions, flat planes of color, bold outlines, and everyday subject matter found in Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e).

Somm was among the first wave of French artists to fall under the spell of Japanese art, beginning his exploration in the late 1860s. His interest was significantly nurtured through his friendship with Philippe Burty (1830-1890), an influential art critic, collector, and early champion of Japanese art in France who actually coined the term "Japonisme." Burty's extensive knowledge and collection provided Somm with invaluable access and insight. Somm's fascination went beyond mere aesthetic appreciation; he reportedly began learning the Japanese language, indicating a deeper desire to understand the culture.

This profound interest manifested clearly in his artwork. He produced numerous watercolors, drawings, and prints, particularly etchings and drypoints, that incorporated Japanese motifs, compositional strategies, and themes. Figures in kimonos, Japanese fans, screens, ceramics, and architectural elements frequently appear in his work, sometimes integrated into Parisian scenes, creating intriguing cultural juxtapositions. He even planned a trip to Japan in the early 1870s, a testament to his dedication, though this ambition was unfortunately thwarted by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). Despite never visiting Japan, its art remained a constant source of inspiration throughout his career.

Navigating the Avant-Garde: The Impressionist Connection

Henry Somm's career intersected with the rise of Impressionism, the dominant avant-garde movement of the 1870s and 1880s. While not a core member of the Impressionist group in the way artists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir were, Somm participated in one of their pivotal exhibitions. In 1879, he was invited to show his work at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition, held on the Avenue de l'Opéra.

This exhibition was notable for its inclusion of several artists who, like Somm, were exploring modern life and innovative techniques but didn't strictly adhere to the Impressionist label. Exhibiting alongside renowned figures such as Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Camille Pissarro, Gustave Caillebotte, and the lesser-known but talented Marie Bracquemond placed Somm firmly within the progressive art circles of the time. His participation suggests that his work, likely his prints and watercolors depicting contemporary Parisian life with a fresh eye, resonated with the Impressionists' broader goals of capturing modernity, even if his style retained a more graphic, linear quality influenced by illustration and Japanese prints rather than the broken brushwork typical of Monet or Renoir. Jean-Louis Forain, another artist known for his sharp observations of Parisian society through drawing and printmaking, also exhibited, highlighting the diverse range of styles encompassed by these independent shows. Paul Gauguin also made one of his early appearances at this exhibition.

Somm's involvement demonstrates his connection to the artistic vanguard and his willingness to align himself with independent artists challenging the official Salon system. It marked a significant moment, positioning him as an artist engaged with contemporary trends and experimental approaches.

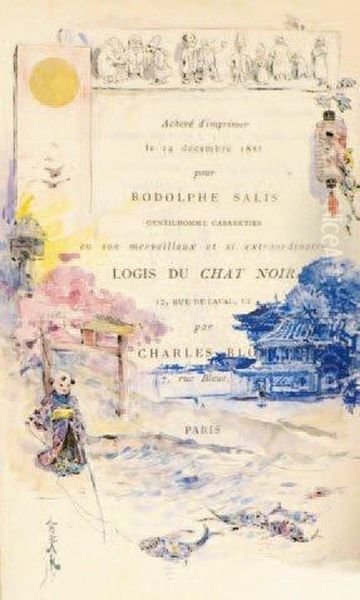

Montmartre and the Spirit of Le Chat Noir

During the 1880s, Somm became deeply involved in the bohemian and artistic life of Montmartre, the hilltop neighborhood overlooking Paris that was rapidly becoming a hub for artists, writers, musicians, and performers. He was a key figure associated with Le Chat Noir ("The Black Cat"), the legendary cabaret founded in 1881 by Rodolphe Salis. Le Chat Noir was more than just a drinking establishment; it was a crucible of artistic innovation, famous for its shadow theatre performances, satirical songs, and avant-garde atmosphere.

Somm was considered one of the founding members or at least an early and integral part of the Le Chat Noir circle. He contributed illustrations to the associated journal, Le Chat Noir, which published poems, stories, and drawings by the cabaret's regulars. His witty, elegant, and sometimes satirical drawings perfectly captured the spirit of the place and the era. He rubbed shoulders with other prominent Montmartre figures who frequented or contributed to Le Chat Noir, including the iconic Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, known for his posters and paintings of Parisian nightlife, as well as Adolphe Willette, Théophile Steinlen (famous for his poster advertising the cabaret), and the caricaturist Caran d'Ache.

His involvement extended beyond illustration. In 1885, Somm reportedly designed the stage sets and illustrations for a comedic shadow play titled "La Berline de l’émigré" performed at the Théâtre d'Ombres (Shadow Theatre) of Le Chat Noir for Christmas. This demonstrates his versatility and his active participation in the collaborative, multi-disciplinary environment fostered by Salis's cabaret. His work for Le Chat Noir cemented his reputation as an artist adept at capturing the pulse of modern Parisian entertainment and society.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Observation, and Line

Henry Somm developed a distinctive and recognizable artistic style characterized by its elegance, refinement, and emphasis on line. While influenced by Impressionism's focus on modern life and Japonisme's decorative qualities, his work retained a strong graphic sensibility, likely stemming from his skills as an illustrator and printmaker.

His preferred subjects often revolved around the contemporary Parisian woman, the Parisienne. He depicted elegant ladies shopping, attending the theatre, strolling in parks, or in moments of private contemplation. These figures are typically rendered with a delicate, fluid line, capturing the fashionable silhouettes and social graces of the Belle Époque. There is often a sense of intimacy and keen observation in these portrayals, sometimes touched with gentle humor or subtle social commentary. Artists like James Tissot and Alfred Stevens also specialized in depicting fashionable women of the era, though Somm's approach often felt lighter and more graphic.

The influence of Japanese prints is pervasive, not just in overtly Japanese themes but also in his compositional choices. He frequently employed asymmetry, flattened perspectives, and decorative patterning, integrating these elements seamlessly into his depictions of Parisian life. His use of empty space could be as evocative as his detailed rendering.

Somm excelled in watercolor and printmaking, particularly etching and drypoint. His watercolors are noted for their subtle washes of color and luminous quality, while his prints showcase his mastery of line – crisp, precise, yet expressive. He used these techniques to create not only standalone artworks but also illustrations for books, magazines (such as Paris à l’eau-forte and Gazette des Paris), menus, calendars, and notably, elegant fan designs, a format particularly suited to his decorative style and Japonisme influences. Félix Buhot, another contemporary printmaker, similarly explored the atmospheric effects and modern subjects of Paris, often with experimental techniques, providing a point of comparison for Somm's graphic work.

Representative Works and Versatility

While perhaps not known for monumental canvases, Henry Somm produced a significant body of work highly regarded for its quality and charm. Identifying specific "masterpieces" can be challenging for an artist primarily known for smaller-scale works and illustrations, but several pieces and series stand out.

His etching Japonisme (1881), now held in collections like the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, is a quintessential example of his engagement with Japanese art. It directly addresses the theme, likely depicting elements associated with the craze for Japanese goods in Paris.

The series of works often referred to as Japanese Women or Japanese Geishas, executed in watercolor or print, are central to his oeuvre. These pieces showcase his ability to adapt Japanese aesthetics and depict figures with grace and sensitivity, capturing details of costume and setting while maintaining his characteristic delicate line.

An Elegant Lady (watercolor) exemplifies his depictions of contemporary Parisian life infused with Japonisme. The work shows a fashionable woman examining an Asian art object, likely in a collector's home or a chic interior, highlighting the intersection of Parisian high society and the taste for the exotic East.

His Calendrier pour 1881 (Calendar for 1881), featuring intricate illustrations for each month, often with Japonisme elements, demonstrates his skill in graphic design and illustration. These calendars, along with his fan designs, were popular and highly sought after, showcasing his ability to apply his artistic talents to decorative objects.

His contributions to journals like Le Chat Noir and Paris à l'eau-forte constitute a significant part of his output, though often unsigned or simply initialed. These illustrations, capturing fleeting moments of Parisian life, theatre scenes, or satirical commentary, reveal his wit and sharp observational skills. His versatility extended to designing posters and participating in theatrical productions, underscoring his role as a multifaceted artist deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of his time.

Influence and Legacy

Henry Somm occupied a unique position in late 19th-century French art, acting as a bridge between different styles and movements. He successfully blended elements of Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, and Japonisme into a cohesive personal style, particularly excelling in the graphic arts.

His influence can be seen in the work of younger artists who were also navigating the complexities of modern Parisian life and the impact of Japanese art. Most notably, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, a fellow Montmartre artist and habitué of Le Chat Noir, admired Somm's work. Lautrec's own innovative use of line, flattened perspectives, and focus on Parisian entertainment venues certainly shares affinities with Somm's approach, suggesting that Somm's elegant graphic style may have been one source of inspiration among others for the younger artist.

Although Somm's fame did not reach the heights of some Impressionist painters or figures like Lautrec, his work has always been appreciated by connoisseurs of printmaking and drawing. His etchings and drypoints, in particular, are prized by collectors for their technical skill, delicate beauty, and evocative portrayal of the Belle Époque. Museums around the world hold examples of his work, recognizing his contribution to French art and the history of Japonisme.

He is remembered as a master of the intimate scale, an artist who captured the nuances of Parisian society with elegance and wit. His deep and early engagement with Japanese art marks him as a significant figure in the Japonisme movement, demonstrating how profoundly non-Western aesthetics could reshape European artistic vision. His work remains a testament to the vibrant cross-currents of art and culture in late nineteenth-century Paris.

Conclusion

Henry Somm was more than just a minor master of the Belle Époque; he was a versatile and sensitive artist whose work reflects the dynamic artistic landscape of his time. From his academic training under Isidore Pils to his participation in the Impressionist exhibitions alongside Degas and Cassatt, his deep immersion in Japonisme fueled by Philippe Burty, and his central role in the creative ferment of Le Chat Noir with Toulouse-Lautrec and Steinlen, Somm's career traced a fascinating path. His elegant depictions of Parisian women, his witty illustrations, and his masterful prints, all infused with a distinctive linear grace and often inspired by Japanese aesthetics, secure his place as a significant contributor to the rich tapestry of late nineteenth-century French art. His work continues to charm and engage viewers, offering a refined and insightful glimpse into a bygone era.