Georges Goursat, universally known by his sharp, memorable pseudonym "Sem," stands as one of the most defining visual commentators of France's Belle Époque. Born in Périgueux in the Dordogne region of France in 1863, Goursat emerged from a prosperous background, a circumstance that would later afford him both intimate access to the world he depicted and the financial independence to pursue his artistic vision without compromise. His legacy is built upon a vast body of work, primarily caricatures, that captured the glittering, often absurd, reality of Parisian high society from the late 19th century until his death in 1934.

Sem was not merely an artist; he was a social historian wielding a pen and brush. His drawings offer an unparalleled window into the exclusive circles of Parisian elites, documenting their fashions, their follies, their leisure activities, and their vanities with an eye that was both amused and astonishingly perceptive. He became a fixture in the very world he satirized, a testament to the charm and accuracy of his portrayals, even when they carried a critical edge.

From Périgueux to Parisian Prominence

Goursat's early life in the provinces provided a foundation, but his artistic destiny lay in the bustling heart of France. His family's wealth, inherited from his father who ran a successful grocery business, allowed him the freedom to cultivate his artistic talents. He did not follow a traditional academic path but developed his distinctive style somewhat independently. His journey into the public eye began not in Paris, but closer to home.

In 1888, choosing the concise pseudonym "Sem," Goursat self-published his first albums of caricatures in Périgueux. This nom de plume was reportedly chosen as a tribute to the earlier master of French caricature, Charles Amédée de Noé, who famously signed his works "Cham." This gesture indicated Goursat's awareness of and respect for the lineage of French graphic satire he was about to join, a tradition already rich with names like Honoré Daumier and Paul Gavarni.

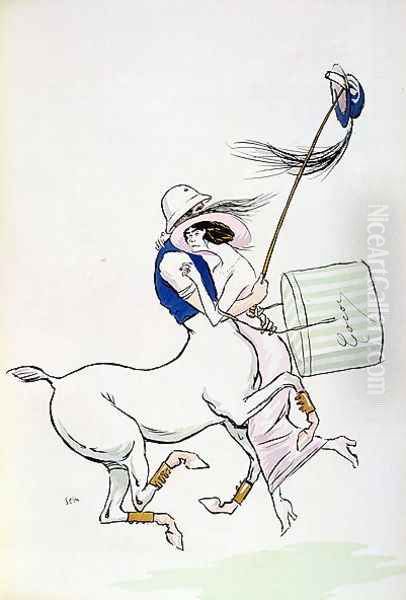

One of these early self-published works, focusing on the world of horse racing, proved particularly successful. Titled Le Turf, this collection showcased his burgeoning talent for capturing the likenesses and characteristic postures of well-known figures frequenting the racecourses. The positive reception encouraged him, and after spending time honing his craft and observing society in cities like Bordeaux and Marseille between 1890 and 1900, Sem made the decisive move to Paris around the turn of the century.

The Artist of Parisian High Life

Paris during the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914) was the undisputed capital of culture, fashion, and pleasure. It was a city of stark contrasts, immense wealth, artistic innovation, and extravagant lifestyles. This vibrant, complex environment became Sem's ultimate subject matter. He immersed himself in the social whirl, becoming a familiar face at the opera, the theaters, the fashionable restaurants like Maxim's, the chic seaside resorts like Deauville and Monte Carlo, and, of course, the ever-important racetracks at Longchamp and Auteuil.

His arrival in Paris marked the beginning of his most prolific and influential period. He quickly gained recognition, publishing his work in leading illustrated journals such as Le Figaro, Le Rire, and L'Illustration. These publications provided a broad platform, bringing his witty observations to a large audience. Sem didn't just draw society; he became part of its fabric, an accepted observer whose presence was noted and whose pencil was both anticipated and perhaps slightly feared.

His method involved keen observation, sketching figures from life, often capturing them in unguarded moments. He possessed an uncanny ability to seize upon a person's most telling gesture, their unique way of standing or walking, or the subtle details of their attire, and exaggerate these elements just enough to create a caricature that was both humorous and instantly recognizable. He chronicled the age of the dandy, the rise of the automobile, the changing silhouettes of women's fashion, and the rituals of elite leisure.

A Distinctive Stylistic Signature

Sem's artistic style is immediately identifiable. It blends elegance with sharp, incisive lines. While clearly rooted in the French tradition of caricature, his work also shows an awareness of other artistic currents. Some critics note the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, particularly in the bold compositions, flattened perspectives, and decorative quality found in some of his works, an influence shared with contemporaries like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Unlike the often darker, more politically charged satire of Daumier, Sem's work generally maintained a lighter, albeit still critical, tone. His focus was more social than political. He utilized lithography for many of his published works, a medium well-suited to reproducing his linear style. However, he is perhaps most celebrated for his masterful use of the pochoir technique.

Pochoir is a sophisticated stenciling process where layers of color are applied by hand using separate stencils for each color. This technique allowed for vibrant, flat areas of color and precise details, giving his albums and prints a luxurious, handcrafted quality that perfectly suited the opulent world they depicted. The resulting images possess a clarity, brightness, and graphic impact that remains striking today. His figures, though caricatured, often move with a certain grace, their elongated forms and fashionable attire rendered with an undeniable chic.

Masterpieces of Observation: Key Works

Throughout his long career, Sem produced numerous albums and countless individual drawings. Among his most celebrated works are the albums that captured specific facets of Belle Époque life. Le Turf (and its subsequent iterations) remained a perennial favorite, documenting the personalities and atmosphere of the racing world, a central pillar of Parisian social life.

In 1914, he published Le Vrai et le Faux Chic (The True and False Chic), a brilliant and witty commentary on the rapidly evolving world of fashion. This album satirized the excesses and pretensions of haute couture, contrasting genuine elegance with awkward trend-following. It featured prominent figures from the fashion world, including the influential designer Paul Poiret, for whom Sem also created some advertising illustrations, demonstrating his engagement with the commercial aspects of visual culture.

His scope extended beyond Paris. Albums like Tangoville-sur-Mer (1913) depicted the fashionable crowds at seaside resorts like Deauville. Notably, this work included sensitive and matter-of-fact portrayals of same-sex couples mingling with heterosexual society, a remarkably progressive inclusion for its time and indicative of Sem's observant, non-judgmental eye for the nuances of social reality.

Sem also created striking posters for destinations like Monte Carlo and Cannes, employing his signature style to evoke the glamour and allure of these playgrounds for the wealthy. Furthermore, one of his most enduring, though perhaps informally associated, images is a drawing frequently linked to Chanel No. 5. While its status as an official advertisement is debated, the elegant, stylized depiction of figures has become symbolically connected with the iconic perfume, showcasing his influence even within the realm of branding.

Sem and the Artistic Landscape

Sem operated within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu. His choice of pseudonym, honoring "Cham," placed him in the lineage of French caricature alongside giants like Daumier and Gavarni. He was a contemporary of other brilliant graphic artists who documented Parisian life, though often with different focuses or styles. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, for instance, shared Sem's interest in Parisian entertainment but focused more intensely on the performers and patrons of cabarets and brothels, employing a more expressive, psychologically probing line.

Other notable contemporaries in the field of illustration and poster art included Jules Chéret, often called the father of the modern poster; Leonetto Cappiello, known for his bold, dynamic advertising images; Théophile Steinlen, famous for his iconic Le Chat Noir poster and his sympathetic depictions of working-class life; and Jean-Louis Forain, another sharp social satirist. While Sem occasionally brushed shoulders with the avant-garde – friendships with figures like the painter Paul César Helleu, known for his elegant drypoint portraits of society women, are noted, and some sources even mention a connection to Paul Cézanne, though stylistic influence seems minimal – his primary domain remained graphic satire and illustration.

His relationship with other artists was complex. He collaborated directly with the artist Auguste Roubille in 1909 to create La Grande Semaine, an ambitious 40-foot circular panorama depicting the bustling life of the Parisian lower classes, showcasing a different facet of his observational skills. However, his sharp wit and focus on satirizing the elite could also place him in a position of perceived competition or critique, particularly concerning the arbiters of fashion and taste like Paul Poiret, whom he both depicted and worked for. His unique position allowed him to interact with figures across the artistic spectrum, from fellow illustrators to painters like the society portraitist Giovanni Boldini, whose glamorous canvases offered a different, less critical, vision of the same world Sem caricatured. He existed alongside the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement, exemplified by Alphonse Mucha, though Sem's style remained distinct from its decorative flourishes.

Witness to War: A Shift in Focus

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a significant rupture in the Belle Époque world that Sem had so meticulously documented. The carefree extravagance and social rituals were overshadowed by the grim realities of conflict. Sem, like many artists, responded to the war, but his approach shifted dramatically. He served as a war correspondent, traveling to the front lines.

During this period, his style underwent a noticeable change. The light, satirical touch largely disappeared, replaced by a more somber, realistic approach. He produced albums like Croquis de Guerre (War Sketches), filled with drawings that depicted the harsh conditions, the exhaustion of soldiers, and the devastation of the battlefield. These works reveal a different side of Sem: the compassionate observer confronted with human suffering on a massive scale. While less known than his society caricatures, these war drawings are powerful documents of their time, demonstrating his versatility and depth as an artist.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

After the war, the world had changed, and the Belle Époque was definitively over. While Sem continued to work, observing the new social landscape of the Années Folles (Roaring Twenties), the peak of his influence coincided with the pre-war era he so perfectly captured. He remained a respected figure in the Parisian art world, continuing to produce illustrations and caricatures.

Georges Goursat, "Sem," died of a heart attack in Paris in 1934, at the age of 71. He left behind an enormous body of work that serves as an invaluable visual record of a specific time and place. His contribution to art history lies not only in his mastery of caricature but also in his role as a social commentator. He documented the end of an era with unparalleled wit, style, and insight.

Sem's influence can be seen in subsequent generations of illustrators and caricaturists. His ability to combine elegance with satire, to capture the essence of personality and social trends through economical lines and vibrant color, remains a benchmark. More than just amusing drawings, his works are sophisticated observations of society, fashion, and human nature. He chronicled the ephemeral world of the Parisian elite, ensuring that the spirit and appearance of the Belle Époque, in all its glamour and absurdity, would be preserved for posterity. His art continues to fascinate, offering a vivid, stylish, and often humorous glimpse into a bygone world, solidifying his position as a unique and indispensable figure in French art history.

A Chronicler for the Ages

Georges "Sem" Goursat was more than a caricaturist; he was the definitive visual diarist of Parisian high society during one of its most fascinating periods. From the racetracks of Longchamp to the tables at Maxim's, from the promenades of Deauville to the trenches of World War I, his sharp eye and skilled hand captured the essence of his time. Influenced by predecessors like Cham and contemporaries like Helleu, while standing distinct from figures like Toulouse-Lautrec or Boldini, Sem carved his own niche. Through iconic works like Le Turf and Le Vrai et le Faux Chic, utilizing techniques like pochoir with masterful effect, he created a legacy that is both artistically significant and historically invaluable. His work remains a witty, elegant, and indispensable window onto the vanished world of the Belle Époque.