Henry Stacy Marks stands as a distinctive figure within the bustling art world of Victorian Britain. Born in London on September 13, 1829, and passing away on January 9, 1898, Marks carved out a unique niche for himself, blending meticulous observation, particularly of birds, with a gentle humour and a strong decorative sense. A member of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, his career spanned painting, illustration, and large-scale decorative commissions, leaving behind a body of work appreciated for both its technical skill and its engaging character.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Henry Stacy Marks entered the world in Great Portland Street, London, the fourth child of John Isaac Marks, a solicitor who later became a coach builder, and Elizabeth Pally. His early inclination towards art led him to seek formal training. After initial studies, he gained admission to the Royal Academy Schools in December 1851, a crucial step for any aspiring artist in Britain at the time. He first saw his work displayed publicly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition in 1853, marking the official start of his professional career.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Marks, like many British artists of his generation, travelled to Paris for further study in 1852 and again in 1856. There, he enrolled in the atelier of François-Édouard Picot at the École des Beaux-Arts. Picot, a respected painter of historical and mythological subjects, provided Marks with a solid grounding in academic technique, though Marks's own style would eventually diverge significantly from that of his master. This period abroad exposed him to different artistic currents and refined his draughtsmanship.

During his early career, Marks showed an affinity for historical and literary subjects, particularly those with medieval or Shakespearean themes. This interest aligned him loosely with the spirit, if not the strict tenets, of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose founders like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt championed detailed realism and subjects drawn from literature and history. Marks's early works often featured anecdotal scenes rendered with careful attention to period detail, demonstrating his burgeoning skills in composition and narrative.

Developing a Unique Niche: The Ornithological Turn

While historical subjects occupied his early years, Henry Stacy Marks gradually found his most distinctive voice in the depiction of birds. This was not merely a casual interest; it became a passionate study. He was a frequent visitor to the London Zoo in Regent's Park, spending countless hours sketching the avian inhabitants, particularly the more exotic species like parrots, cranes, and storks. His fascination went beyond surface appearance; he studied their anatomy and behaviour, seeking to capture their individual character and, often, their unintentionally comical aspects.

This dedication to ornithological accuracy, combined with a warm sense of humour, became his trademark. His bird paintings were rarely simple scientific illustrations. Instead, Marks often imbued his subjects with personality, placing them in amusing situations or highlighting their quirky postures and expressions. This anthropomorphic tendency, handled with subtlety, charmed audiences and critics alike. He even authored works demonstrating his scientific interest, such as the intriguingly titled A Treatise on Parrots.

His growing reputation in this field likely contributed significantly to his professional advancement. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1871 and achieved full Academician status (RA) in 1878. While records sometimes vary, it's widely believed that a major bird painting, possibly St Francis Preaching to the Birds or another significant ornithological piece exhibited around that time, served as his diploma work or was instrumental in his election. His studies, such as the Study of Two Vultures, were admired for their precision and insight, even attracting the attention of the influential critic John Ruskin, who acquired some for educational purposes, eventually finding their way into the teaching collections at Oxford University.

Decorative Arts and Major Commissions

Marks's artistic talents were not confined to easel painting. He was highly sought after for decorative work, contributing significantly to the visual culture of public and private spaces in Victorian England. His skill in designing large-scale compositions, often incorporating his favoured avian or historical motifs, made him a versatile collaborator for architects and patrons.

One of his most prominent public commissions was the design of a large terracotta frieze for the exterior gallery of the Royal Albert Hall in London. This vast undertaking depicted figures representing various arts and sciences, showcasing Marks's ability to work on an architectural scale and in durable materials. The frieze remains a significant feature of this iconic building, a testament to his public art contributions.

He also undertook extensive decorative schemes for private patrons. Perhaps the most notable was his work for Hugh Grosvenor, the 1st Duke of Westminster, at Eaton Hall in Cheshire. Marks designed elaborate decorations, including friezes and panels, often featuring birds. His work for the Duke included a series of paintings depicting birds for a specially designed 'Bird Room' or aviary library, showcasing his expertise in ornithological art within a grand domestic setting. Another example of his decorative work includes the painting The Welcome (1862), created for the architect William Robert Edis, demonstrating his ability to tailor his art to specific architectural contexts and client needs. This aspect of his career places him within the broader Victorian interest in integrated design, echoed in the work of figures like William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, though Marks retained his own distinct style.

The St John's Wood Clique and Artistic Milieu

Henry Stacy Marks was a central figure in the St John's Wood Clique, an informal group of artists based in the St John's Wood area of London, known for its concentration of artists' studios. This group, active primarily from the 1860s through the 1880s, shared friendships, social gatherings, and a generally similar approach to art, though each maintained their individual style. Core members, besides Marks, included Philip Hermogenes Calderon, George Dunlop Leslie, William Frederick Yeames, George Adolphus Storey, David Wilkie Wynfield (also a noted photographer), and later John Evan Hodgson.

The Clique favoured narrative subjects, often drawn from history or literature, rendered in a clear, accessible, and technically proficient manner. They generally avoided the high moral seriousness of the early Pre-Raphaelites or the avant-garde tendencies emerging later in the century. Humour was a frequent element in their work, a characteristic particularly evident in Marks's paintings. Their pictures were popular with the public and sold well at the Royal Academy exhibitions.

Marks, known for his sociable nature and wit, was reportedly a key personality within the group. Their gatherings were known for camaraderie and mutual support. While not a formal 'school' with a manifesto, the Clique represented a significant strand of mainstream Victorian art, focusing on storytelling, relatable emotions, and skilled execution. Marks's involvement underscores his position within the established art community of his time, sharing sensibilities with his peers while cultivating his unique specialisation in bird life and humorous observation. His own writings suggest a pragmatic view of the art world; he reportedly criticized the Royal Academy for promoting outdated genre painting styles, advocating instead for public judgment to determine artistic merit.

Later Career and Notable Works

Throughout the later decades of his career, Henry Stacy Marks continued to be a prolific and popular artist. He remained a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy and other major venues. While bird subjects remained central, he continued to explore other themes, often infused with his characteristic blend of observation and gentle wit.

One of his well-regarded later works is The Committee of Selection (1891), now housed in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. This painting humorously depicts a group of parrots seemingly engaged in a serious deliberation, a clever commentary perhaps on academic committees or judgment panels, delivered through his favoured avian subjects. It exemplifies his mature style, combining detailed rendering with narrative humour.

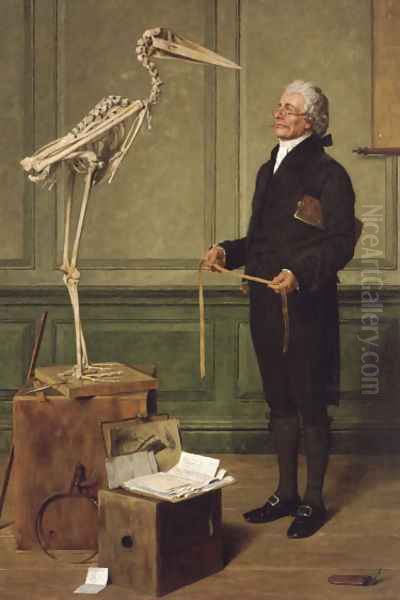

Another painting, Science is Measurement, reflects his enduring interest in scientific observation, possibly depicting a scholar or alchemist figure, linking back to his earlier historical themes but perhaps also nodding to the increasing importance of science in the Victorian era. The work A Fish Out of Water (1895), painted towards the end of his life, might suggest themes of displacement or adaptation, interpreted through a natural history lens.

His illustrations for Shakespearean plays, such as his depiction of Dogberry from Much Ado About Nothing, continued to be appreciated for their characterful interpretations. These works, often reproduced as prints, helped to disseminate his art to a wider audience beyond the gallery walls. His commitment to both fine art and decorative commissions continued, demonstrating a work ethic and artistic curiosity that persisted throughout his life.

Personal Life and Final Years

Henry Stacy Marks married Helen Pendril Coulson in 1856. The couple enjoyed a long marriage until Helen's death in 1892. This loss deeply affected Marks. The following year, in 1893, he remarried. His second wife was Mary Harriet Kempe, herself a painter, indicating a continued connection to the artistic community even in his personal life. This union brought him a son, Walter Marks.

Marks spent much of his later life residing at 15 Hamilton Terrace in St John's Wood, placing him geographically at the heart of the artistic community he was associated with. He remained active in the art world, though his output may have slowed in his final years.

Henry Stacy Marks passed away at his London home on January 9, 1898, at the age of 68. He was buried in Hampstead Cemetery, London. His death marked the passing of a well-loved and respected figure in the Victorian art establishment, an artist who had successfully navigated the demands of academic tradition, public taste, and personal artistic inclination.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Henry Stacy Marks's artistic style evolved over his career but retained several core characteristics. His early work, influenced by historical and literary themes, showed a commitment to detailed realism and narrative clarity, aligning with broader Victorian trends and echoing aspects of Pre-Raphaelitism. However, he soon developed a more personal style, particularly after focusing on ornithological subjects.

His depiction of birds was marked by meticulous observation, capturing anatomical accuracy, plumage detail, and characteristic poses. Yet, he transcended mere illustration by infusing his subjects with personality and often placing them in humorous or narrative contexts. This blend of scientific accuracy and gentle anthropomorphism became his signature. His skill rivalled that of dedicated animal painters like Sir Edwin Landseer, but Marks brought a lighter, often more whimsical touch to his subjects.

Marks was proficient in both oil and watercolour. His watercolours, particularly his bird studies, are noted for their freshness and delicacy. In his decorative work, he demonstrated adaptability, designing effectively for different materials and scales, from terracotta friezes to painted panels. His compositions are generally well-structured, his drawing precise, and his use of colour clear and effective, often favouring strong local colours in his bird paintings. His humour was typically gentle and observational rather than satirical or biting.

Legacy and Collections

During his lifetime, Henry Stacy Marks enjoyed considerable popularity and critical respect. He was a stalwart of the Royal Academy and his works were sought after by collectors both in Britain and the United States. His specialization in bird painting secured him a lasting reputation in that genre, where he remains a key Victorian exponent. His ability to combine accurate representation with character and humour gave his work a broad appeal that has endured.

His legacy is also preserved through his contributions to decorative art, most notably the Royal Albert Hall frieze, which remains a public landmark. His association with the St John's Wood Clique places him within an important social and artistic network of the period.

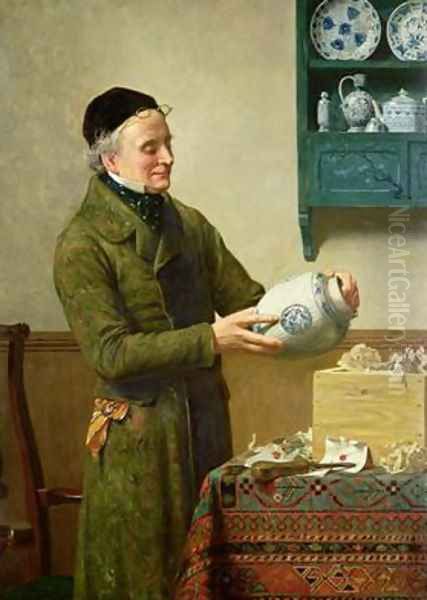

Works by Henry Stacy Marks are held in numerous public collections. The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool holds his significant painting The Committee of Selection. The Royal Academy of Arts in London holds works, including potentially his diploma piece. The Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery (RAMM) in Exeter possesses A Bit of Blue, a painting noted for reflecting the aesthetic tastes associated with the Regency period, though painted later by Marks. Oxford University's teaching collections include his detailed Study of Two Vultures, originally acquired by John Ruskin. A sketch related to his The Seasons design can be found at St Agnes House. These holdings ensure that his work remains accessible for study and appreciation.

Conclusion

Henry Stacy Marks navigated the Victorian art world with skill, versatility, and a distinctive personal vision. From his early historical scenes to his celebrated bird paintings and significant decorative commissions, he demonstrated technical proficiency and an engaging artistic personality. His unique ability to blend careful observation, particularly of the natural world, with narrative interest and gentle humour set him apart. As a key member of the St John's Wood Clique and a respected Royal Academician, he contributed significantly to the artistic fabric of his time. His legacy endures through his charming and meticulously rendered depictions of birds and his contributions to the decorative arts, securing his place as a notable and well-loved figure in British art history.