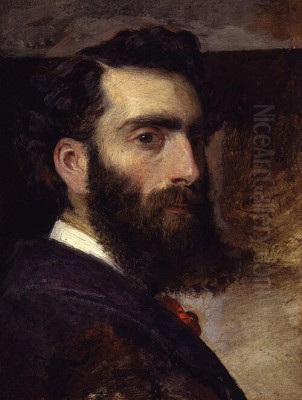

Philip Hermogenes Calderon stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Victorian art. Born in Poitiers, France, on May 3, 1833, his mixed European heritage—a Spanish father and a French mother—perhaps contributed to the unique sensibility he brought to the British art scene. Though he would become a quintessential Victorian painter, his early life and influences were distinctly cosmopolitan. His father, Juan Calderón, was a former Roman Catholic priest who had converted to Anglicanism and later became a respected professor of Spanish literature at King's College, London. This intellectual and culturally diverse family background undoubtedly shaped the young Calderon.

Initially, Philip Hermogenes Calderon was not destined for a career in the arts. His early education pointed towards a more practical path, with plans for him to study engineering. However, a burgeoning interest in the precision and artistry of technical drawing and diagrammatic representation soon revealed a deeper artistic inclination. This passion for visual expression ultimately led him to abandon engineering and dedicate himself to painting, a decision that would enrich the British art world for decades.

Artistic Formation and Early Influences

Calderon's formal artistic training began in London in 1850 at Leigh's art school, a well-regarded institution run by James Mathews Leigh. This provided him with a solid foundation in drawing and painting techniques. Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Calderon, like many aspiring artists of his generation, looked to Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. In 1851, he traveled to the French capital and enrolled in the atelier of François-Édouard Picot. Picot was a respected academic painter, known for his historical and mythological scenes, and his studio would have exposed Calderon to the rigorous discipline of the French academic tradition, emphasizing strong draughtsmanship and carefully constructed compositions.

This period of study in Paris was crucial. It allowed Calderon to absorb contemporary European artistic trends while refining his technical skills. The French academic system, with its emphasis on history painting and the human figure, would leave a lasting impression on his work, even as he developed his own distinct style upon his return to England. He was not alone in seeking Parisian training; artists like Frederic Leighton and Edward Poynter also benefited from continental study, bringing a sophisticated European influence to British art.

Upon returning to London, Calderon quickly began to make his mark. He first exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy in 1853 with a painting titled By the Waters of Babylon. This work, depicting the sorrow of the exiled Israelites, was well-received and signaled the arrival of a promising new talent. It showcased his burgeoning ability to convey emotion and narrative, themes that would become central to his oeuvre. The painting’s detailed execution and emotive subject matter also hinted at an affinity with the burgeoning Pre-Raphaelite movement, which was then challenging the established artistic conventions in Britain.

The Pre-Raphaelite Orbit and the St. John's Wood Clique

While not a formal member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, Calderon's early work clearly shows their influence. The PRB advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colours, and complex compositions found in art before Raphael, emphasizing truth to nature and often drawing on literary, historical, and religious themes. Calderon’s meticulous attention to detail, his rich colour palette, and his choice of emotionally charged subjects resonated with these ideals.

His painting Broken Vows, exhibited in 1856, became one of his most famous early works and is often cited as a prime example of Pre-Raphaelite influence in his art. The painting depicts a young woman, concealed behind a garden wall, overhearing her lover betraying her with another. The intense emotion of the scene, the detailed rendering of the foliage, and the moral undertones are all characteristic of the Pre-Raphaelite sensibility. The work was immensely popular, widely reproduced as an engraving, and cemented Calderon's reputation. It demonstrated his skill in creating what became known as "problem pictures"—narrative scenes that invited viewers to interpret the story and its implications, often leaving a degree of ambiguity.

Calderon was a key figure in the St. John's Wood Clique, a group of artists who shared studios and socialized in the St. John's Wood area of London. This informal association included painters such as William Frederick Yeames (famous for And When Did You Last See Your Father?), George Dunlop Leslie, Henry Stacy Marks, George Adolphus Storey, and David Wilkie Wynfield. While diverse in their individual styles, they shared an interest in historical genre painting, often imbued with a narrative or anecdotal quality, and a commitment to skilled craftsmanship. The Clique provided a supportive environment for these artists, fostering a spirit of friendly rivalry and mutual encouragement. Their work, including Calderon's, often focused on accessible historical or literary themes, appealing to the Victorian public's appetite for storytelling in art.

Mature Style: Historical Narratives and Emotional Depth

As Calderon's career progressed, he increasingly focused on historical and literary subjects, often depicting poignant moments or dramatic encounters. His paintings were characterized by their careful research, strong compositional sense, and an ability to capture the psychological state of his figures. He had a particular talent for portraying female subjects, investing them with grace, dignity, and emotional complexity. Works like Juliet (1872), depicting Shakespeare's tragic heroine in a moment of contemplation on her balcony, showcase his romantic sensibility and his skill in rendering textures and atmosphere. The soft lighting and the pensive mood of Juliet are typical of his mature approach to literary themes.

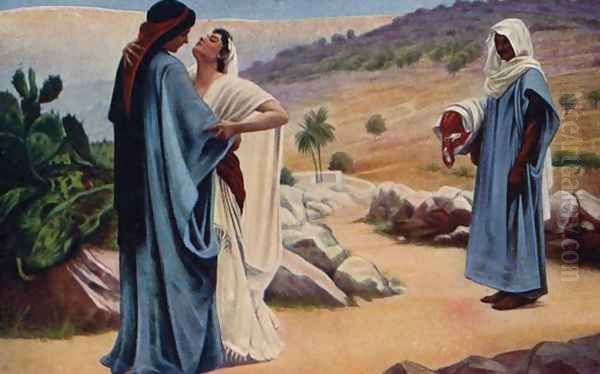

Another significant work from this period is Ruth and Naomi (1886), which illustrates the tender and loyal bond between the two biblical figures. Calderon’s treatment of the subject emphasizes the human emotion and devotion inherent in the story, rendered with a characteristic sensitivity and attention to historical detail. His ability to translate well-known narratives into compelling visual dramas was a hallmark of his art. He often chose subjects that allowed for the exploration of universal human emotions such as love, loss, betrayal, and faith.

His paintings frequently featured elaborate costumes and settings, reflecting the Victorian fascination with historical accuracy and romanticized depictions of the past. However, beyond the surface appeal of these historical reconstructions, Calderon's best work delved into the inner lives of his characters. He was less interested in grand, heroic battle scenes than in the more intimate human dramas that unfolded within historical contexts. This focus on personal experience and emotion distinguished his work from some of the more bombastic historical painters of the era, such as perhaps some of the military scenes by artists like Lady Butler (Elizabeth Thompson).

Controversy and Later Works

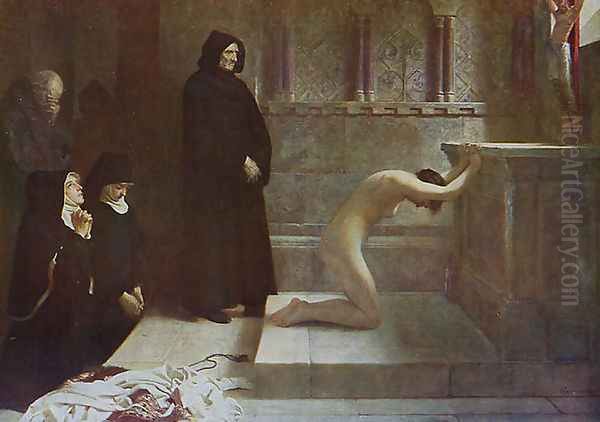

One of Calderon's most ambitious and controversial paintings was The Renunciation of St. Elizabeth of Hungary (also known as St. Elizabeth of Hungary's Great Act of Renunciation), exhibited in 1891. The large canvas depicts the 13th-century saint, having given away her wealth and possessions, kneeling naked before an altar as she dedicates her life to God. The painting was commissioned under the terms of the Chantrey Bequest, a fund established to purchase works of art for the nation.

The depiction of a female saint in a state of nudity, even in a religious context, caused considerable public outcry and debate. Some critics and members of the public found it shocking and inappropriate, while others defended it as a powerful representation of religious devotion and self-sacrifice. The controversy highlighted the often-conservative tastes of the Victorian public and the challenges faced by artists who pushed an_y boundaries. Despite the debate, or perhaps partly because of it, the painting remains one of Calderon's most discussed works. It demonstrated his willingness to tackle complex and potentially provocative subjects, and his skill in composing large-scale, multi-figure compositions.

Another work from this later period, The Redemption of St. Mary Magdalen (1891), also dealt with a religious theme and was acquired for the Chantrey Bequest. This painting, too, could be interpreted through various lenses, reflecting the complex religious currents of the late Victorian era. Calderon's engagement with such themes, often tinged with a subtle humour or irony in his earlier works, became more overtly serious in these later religious paintings. His Roman Beauty (1887) showcases a different facet, focusing on the aesthetic appreciation of classical female beauty, a popular theme among artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Frederic Leighton, though Calderon's approach often retained a more narrative or character-driven focus.

Role at the Royal Academy and Legacy

Philip Hermogenes Calderon was highly respected within the British art establishment. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1864 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1867. His standing was further recognized in 1887 when he was appointed Keeper of the Royal Academy. This was a significant and influential position, effectively making him the head of the Royal Academy Schools. In this role, he was responsible for overseeing the education and training of young artists, a testament to his own technical mastery and his esteemed position within the artistic community. He succeeded notable figures in this role and worked alongside presidents of the RA like Sir Frederic Leighton and later Sir Edward Poynter.

His tenure as Keeper allowed him to influence a new generation of artists, and he was known for his dedication to the Schools. He took his responsibilities seriously, maintaining the high standards of instruction for which the Royal Academy was known. His own artistic practice, with its emphasis on strong drawing, careful composition, and narrative clarity, provided a model for students.

Calderon continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. His works were popular with the public and generally well-received by critics, although, like many Victorian painters, his reputation experienced a decline in the early 20th century with the rise of modernism. Artists like Walter Sickert or Philip Wilson Steer, who were embracing more impressionistic or post-impressionistic styles, began to capture the avant-garde imagination. However, there has been a renewed appreciation for Victorian art in recent decades, and Calderon's contributions are increasingly recognized.

Philip Hermogenes Calderon passed away in London on April 30, 1898, at the age of 64. He left behind a substantial body of work that reflects the artistic concerns and tastes of his era. His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including Tate Britain, which houses Broken Vows, ensuring its continued visibility.

Personal Anecdotes and Character

Beyond his public artistic career, glimpses of Calderon's personality and life emerge from contemporary accounts. His father's journey from Catholic priest to Anglican academic provided a unique family backdrop. There's a charming anecdote that his initial foray into art was spurred by his enjoyment of the precision required for engineering drawings, suggesting an early appreciation for meticulous detail that would later define his painting style.

His association with the St. John's Wood Clique points to a sociable nature and a capacity for collaborative friendship. The group was known for its camaraderie, and their shared artistic pursuits undoubtedly enriched their individual practices. Some accounts suggest a humorous element to his character, which occasionally found its way into his paintings, particularly in his earlier genre scenes. This ability to inject subtle wit or irony into his work added another layer of appeal for his Victorian audience.

There's a mention of his sister, Henrietta Markies, playing a role in protecting his artistic career through her marriage, though the specifics of this are not widely detailed. It hints at the supportive family network that can be crucial for an artist's success. Calderon himself married Clara Storey, the sister of his fellow St. John's Wood Clique member, George Adolphus Storey, further cementing his ties within this artistic circle.

Art Historical Evaluation

In the broader context of art history, Philip Hermogenes Calderon is primarily recognized as a leading exponent of Victorian narrative painting. He successfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, absorbing the influence of Pre-Raphaelitism while developing a distinct style that blended detailed realism with emotional storytelling. His work often focused on historical, literary, and biblical themes, rendered with technical skill and a keen understanding of human psychology.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as the original Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, or as grand in scope as academic classicists like Leighton or Alma-Tadema, Calderon carved out a significant niche for himself. His "problem pictures," like Broken Vows, engaged the Victorian public's imagination and contributed to a popular mode of art consumption that valued narrative interpretation and moral reflection. His later, more controversial works, such as The Renunciation of St. Elizabeth of Hungary, demonstrated his ambition and his willingness to tackle challenging subjects, even at the risk of public censure.

His role as Keeper of the Royal Academy further underscores his importance within the Victorian art establishment. He was not an outsider rebel but an artist who achieved success and influence within the system, contributing to the education of future generations. Today, his paintings offer valuable insights into the cultural values, aesthetic preferences, and narrative preoccupations of the Victorian era. They stand as testaments to a skilled and thoughtful artist who masterfully captured the stories and emotions that resonated with his time, and which continue to engage viewers today. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman, a compelling storyteller, and an important contributor to the rich and diverse landscape of 19th-century British art, holding his own alongside contemporaries like Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, or Marcus Stone, who also excelled in narrative and genre painting.