Charles Hunt, born in 1803 and passing away in 1877, stands as a notable figure in the rich tapestry of British art, particularly renowned for his contributions as an engraver during a period of immense popularity for sporting and coaching prints. While the name "Hunt" resonates through several generations of British artists, often leading to confusion, Charles Hunt the engraver carved a distinct niche for himself through his prolific output and technical skill, primarily in the demanding medium of aquatint. His work vividly captures the dynamism and social customs of 19th-century Britain, focusing on the thrills of the turf, the bustle of the coaching era, and the traditions of the hunt.

Living and working through a transformative period in British history, Hunt's engravings serve not only as artistic endeavours but also as valuable historical documents. They reflect a society fascinated by speed, sport, and the changing landscape of transportation just before the dominance of the railway. His prints, often hand-coloured, brought the vibrant paintings of contemporary sporting artists into the homes of a wider public, playing a crucial role in the dissemination of popular imagery.

The Hunt Artistic Lineage: A Talented but Tangled Web

The name Hunt is associated with several British artists, sometimes leading to conflation of identities and achievements. Charles Hunt (1803-1877), the subject of this discussion, focused his career on engraving. It is important to distinguish him from other notable Hunts. For instance, there was another painter named Charles Hunt (1829-1900), known for his detailed genre scenes, often featuring domestic interiors and animals, whose sons, Edgar Hunt (1876-1953) and Walter Hunt (1861-1941), became highly successful painters of farmyard scenes and animals, carrying the family's artistic inclinations into the early 20th century. Their meticulous style, focusing on the textures of fur and feather, differs significantly from the engraved work of the earlier Charles Hunt.

Furthermore, the celebrated watercolourist William Henry Hunt (1790-1864), known affectionately as 'Bird's Nest' Hunt for his exquisite still lifes of fruit, flowers, and nests, was a contemporary but not a direct relative in the immediate line of Charles Hunt the engraver. William Henry Hunt developed a unique stippling technique in watercolour and was influenced by figures like Dr. Thomas Monro and the watercolour master John Varley. His focus on intimate still life and rustic figures contrasts sharply with the sporting themes favoured by Charles Hunt (1803-1877).

Adding to potential confusion is the major figure of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, William Holman Hunt (1827-1910). A painter of profound religious and symbolic works like The Light of the World and The Scapegoat, Holman Hunt's artistic aims, style, and social circle (including John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti) were entirely different from those of Charles Hunt the engraver. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for appreciating the specific contributions of Charles Hunt (1803-1877) within the correct historical and artistic context.

The Golden Age of Sporting Prints

Charles Hunt's career flourished during a peak period for British sporting art and printmaking. The late 18th and early 19th centuries had seen the rise of exceptional animal painters like George Stubbs and Ben Marshall, who elevated equestrian portraiture to a high art. Following them, a generation of artists specialized in capturing the action and social milieu of horse racing, coaching, and hunting, finding a ready market among the landed gentry and burgeoning middle class.

Prints were the primary means by which these images reached a wider audience. Engraving techniques, particularly mezzotint and aquatint, allowed for the reproduction of paintings with tonal depth and atmospheric effects. Aquatint, in which Hunt excelled, was especially suited for rendering the varied textures of landscapes, the sleek coats of horses, and the dramatic weather often depicted in coaching and hunting scenes. The process allowed for broad areas of tone to be etched onto the copper plate, creating effects similar to watercolour washes.

The demand for these prints was fueled by a national passion for horse racing – the "Sport of Kings" – and a nostalgic attachment to the coaching system, which was reaching its zenith just as the railways began to pose a threat. Prints depicting famous Derby or St. Leger winners, celebrated coaches navigating perilous roads, or lively fox hunting meets were immensely popular decorative items and collector's pieces. Charles Hunt entered this thriving market, bringing considerable technical skill to the reproduction of works by leading sporting painters.

Mastery of Aquatint Engraving

Charles Hunt's reputation rests significantly on his mastery of the aquatint technique. Developed in the late 18th century, aquatint allowed engravers to achieve tonal effects rather than relying solely on lines. The process involves dusting the copper plate with powdered resin, which, when heated, adheres to the plate. Acid is then used to bite the plate between the resin particles, creating a pitted surface that holds ink and prints as a tonal area. By varying the density of the resin and the etching times, engravers could achieve a wide range of tones, from delicate light greys to deep, rich blacks.

Hunt demonstrated exceptional control over this intricate process. His aquatints are characterized by their clarity, fine tonal gradations, and ability to capture atmospheric perspective. He skillfully translated the painterly qualities of the original oils or watercolours into the engraved medium. This was particularly important for coaching scenes set in specific weather conditions – misty mornings, rain-lashed roads, or bright, clear days – where the aquatint ground could effectively convey the ambient light and mood.

Many of Hunt's prints were subsequently hand-coloured, often by teams of colourists working for the print publishers. While Hunt himself was responsible for the engraved plate, the final appearance of the popular prints owed much to this colouring process, which added vibrancy and appeal. Hunt's well-defined engraved lines and clear tonal areas provided an excellent base for the colourists, ensuring consistency and quality in the finished product. His technical proficiency made him a sought-after engraver by artists and publishers alike.

Collaboration: Engraving After the Masters

A significant portion of Charles Hunt's output involved engraving the works of other prominent artists, particularly those specializing in sporting and coaching subjects. His role was primarily that of an interpretive engraver, translating a painting's composition, detail, and spirit into a printable format. This required not only technical skill but also a sympathetic understanding of the original artist's style and intent. His success in this field is evident from the high regard in which his prints are held and the frequency with which he worked after the leading painters of the day.

Perhaps his most notable collaboration was with John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865). Herring was one of the pre-eminent horse painters of the era, famed for his portraits of race winners, particularly those of the St. Leger and Derby, as well as his farmyard scenes. Hunt engraved numerous works after Herring, capturing the artist's detailed anatomical accuracy and the glossy sheen of the horses' coats. These prints, depicting legendary horses and classic races, were immensely popular and helped solidify Herring's fame while showcasing Hunt's engraving talents.

Hunt also frequently engraved works by Henry Alken (1785-1851), an artist known for his dynamic and often humorous depictions of hunting, racing, coaching, and shooting. Alken's style was energetic and full of incident, and Hunt's engravings successfully captured this liveliness. Series like Alken's Sporting Anecdotes were brought to a wider public through engravings by Hunt and others.

James Pollard (1792-1867) was another key artist whose coaching and racing scenes were expertly translated into prints by Charles Hunt. Pollard specialized in detailed depictions of mail coaches, coaching inns, and famous races like the Epsom Derby. Hunt's engravings after Pollard are highly valued for their accuracy and evocative portrayal of the coaching age. Similarly, Hunt engraved scenes by William Shayer Sr. (1787-1879), known for his rustic landscapes often incorporating coaching or rural life elements. These collaborations highlight Hunt's central role in the ecosystem of sporting art production and dissemination in the 19th century. He also engraved works after artists like Sir Francis Grant, known for his portraits and sporting conversation pieces.

The World Through Hunt's Engravings: Themes and Subjects

Charles Hunt's engraved work provides a fascinating window into the popular pastimes and social landscape of 19th-century Britain. His subjects predominantly revolved around the horse, reflecting its central importance in transport, sport, and rural life.

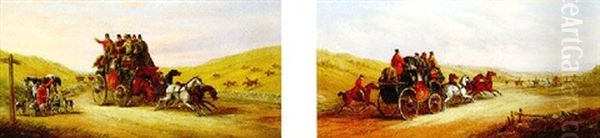

Coaching Scenes: Hunt produced a vast number of coaching prints, capturing the romance, danger, and daily reality of travel before the railways. These scenes often depicted mail coaches travelling at speed along country roads, changing horses at bustling inns, navigating treacherous weather conditions, or experiencing mishaps. Engravings like The London to Brighton Mail Coach or scenes depicting specific named coaches (e.g., 'Quicksilver', 'Tantivy') were highly sought after. They evoke a sense of energy, movement, and the picturesque quality of road travel, often tinged with nostalgia as the coaching era drew to a close.

Racing Scenes: The thrill of the turf was another major theme. Hunt engraved numerous portraits of famous racehorses, often Derby or St. Leger winners, meticulously reproducing the work of painters like J.F. Herring Sr. He also captured the spectacle of race days, depicting crowded courses, the start or finish of important races, and the elegant spectators. These prints celebrated equine speed and stamina and catered to the widespread interest in betting and horse breeding. Titles often specified the horse, the race, and the year, adding to their documentary value.

Hunting Scenes: Fox hunting, steeplechasing, and other field sports were staples of Hunt's repertoire, often engraved after artists like Henry Alken. These prints conveyed the excitement of the chase, the relationship between rider, horse, and hounds, and the beauty of the British countryside. Series depicting the different stages of a hunt, from the meet to the kill, were particularly popular, offering narrative interest alongside sporting action.

While primarily known for these sporting themes, Hunt's work occasionally encompassed other subjects related to country life or transport, always executed with his characteristic attention to detail and mastery of the aquatint medium. The consistency and quality across his chosen themes solidified his reputation among publishers and collectors.

Style, Technique, and Artistic Interpretation

As an engraver, Charles Hunt's 'style' is best understood through his technical execution and his interpretation of the source material. His engraved line work was typically precise and clear, defining forms effectively. However, it was his use of aquatint that truly distinguished his work, allowing for subtle modelling, atmospheric depth, and the rendering of textures – the rough surface of a country road, the smooth flank of a horse, the billowing clouds in the sky.

When considering claims found in some sources about his work – such as "detailed brushwork" or "rich colours" – it's important to remember he was primarily an engraver. These descriptions likely refer either to the qualities of the original paintings he was reproducing or, more often, to the hand-colouring applied to the prints after they were pulled from the plate. Hunt's engraved foundation, however, was crucial for the success of the final coloured image.

His ability to convey movement and speed was essential for his subject matter. In racing scenes, the horses appear dynamic and full of energy. In coaching prints, the sense of momentum, the straining of the horses, and the turning of the wheels are palpable. This was achieved through skillful drawing translated into engraved lines and tones, capturing the fleeting moments of intense action.

The description of his work as exhibiting "naturalism" and "faithful depiction" aligns well with the aims of sporting art during this period. Accuracy in depicting the anatomy of horses, the details of carriages and tack, and the specifics of locations or events was highly valued by patrons and the public. Hunt excelled at rendering these details faithfully, contributing significantly to the documentary aspect of his prints. His work, while interpretive, aimed for clarity and accuracy in conveying the scene as painted by the original artist.

Career, Recognition, and the Market

Charles Hunt was highly productive throughout his career, spanning several decades from the 1820s into the latter half of the 19th century. His prints were issued by prominent London publishers who specialized in sporting subjects, ensuring wide distribution. While specific records of awards won solely for engraving might be scarce (unlike medals awarded for painting at major exhibitions), the sheer volume of his output and the consistent demand for his prints attest to his success and recognition within the printmaking trade and the art market.

He did exhibit works, likely prints, at London venues, including the Society of British Artists at Suffolk Street. While some sources mention Royal Academy exhibitions, clarity is needed as multiple artists named Hunt exhibited there over different periods. Charles Hunt the engraver's primary recognition came through the commercial success and widespread appreciation of his published prints rather than academic honours.

His reputation was intrinsically linked to the painters whose work he translated. The popularity of artists like Herring, Alken, and Pollard directly fueled the demand for Hunt's engravings after their paintings. He operated within a collaborative commercial art world where painters, engravers, colourists, and publishers all played vital roles.

The claim sometimes encountered regarding "poor social skills" potentially limiting his fame is difficult to substantiate specifically for Charles Hunt (1803-1877) and might stem from confusion with other artists, such as the more reclusive watercolourist William Henry Hunt. Charles Hunt the engraver appears to have been a steady and reliable professional craftsman who successfully navigated the commercial print market for decades.

Legacy: Documenting an Era in Aquatint

Charles Hunt's legacy lies in the substantial body of high-quality engravings he produced, which capture a vibrant slice of 19th-century British life. As a master of the aquatint technique, he skillfully translated the works of leading sporting painters into prints that were both artistically accomplished and immensely popular. His work played a crucial role in disseminating images of horse racing, coaching, and hunting to a broad audience, contributing significantly to the visual culture of the era.

His prints remain highly collectible today, valued not only for their aesthetic qualities and technical execution but also as historical documents. They offer vivid insights into the transport, pastimes, and social customs of Georgian and Victorian Britain, particularly the world centered around the horse. Comparing his work to other engravers of the period, such as Thomas Sutherland or the Havell family (Robert Havell Sr. and Jr.), places him firmly within the top tier of reproductive engravers specializing in sporting subjects. One might also consider the work of engravers like Thomas Landseer, who also tackled animal subjects, though often with a different emphasis.

While the Hunt family name connects several distinct artistic talents, Charles Hunt (1803-1877) holds a specific and important place as a dedicated engraver. He chronicled the energy and character of the sporting world with precision and artistry, leaving behind a rich visual record that continues to fascinate historians and art lovers alike. His mastery of aquatint ensured that the dynamic paintings of his contemporaries reached far beyond the gallery wall, becoming part of the fabric of popular visual culture in 19th-century Britain.