Introduction: An Antwerp Painter of Festivities

Hieronymus Janssens, born in Antwerp in 1624 and active until his death in 1693, holds a distinct place within the rich tapestry of Flemish Baroque art. While the era is often dominated by the grand religious and mythological narratives of masters like Peter Paul Rubens or the refined portraiture of Anthony van Dyck, Janssens carved a unique niche for himself. He became renowned for his lively and elegant depictions of social gatherings, particularly balls and dances, earning him the evocative nickname 'Den Danser' – The Dancer. His work offers a fascinating window into the leisure activities and social customs of the affluent classes in the Southern Netherlands during the 17th century, rendered with the characteristic dynamism and flair of the Baroque style.

Janssens operated within the vibrant artistic milieu of Antwerp, a city that, while past its absolute economic zenith, remained a crucial center for art production and innovation. He absorbed the prevailing artistic currents, translating the drama and decorative richness of the Flemish Baroque into the more intimate, yet still theatrical, realm of genre painting. His canvases are typically filled with gracefully interacting figures, sumptuous costumes, and elaborate architectural settings, capturing moments of joy, courtship, and sophisticated entertainment. Understanding Janssens means exploring the intersection of genre painting, Baroque aesthetics, and the specific cultural context of 17th-century Antwerp.

Early Life, Training, and Guild Recognition

Hieronymus Janssens' artistic journey began formally in the years 1636-1637 when he was registered as a pupil of Christoffel van der Lamen (also sometimes recorded as van der Laken, c. 1606–c. 1652). This apprenticeship was formative. Van der Lamen himself specialized in genre scenes, particularly 'merry companies' – depictions of elegantly dressed figures enjoying music, games, or meals, often indoors. Janssens clearly absorbed his master's thematic interests, focusing on similar subject matter involving leisure and social interaction among the well-to-do.

The influence of Van der Lamen can be seen in Janssens' early attention to detail in costume and setting, and the general theme of refined social gatherings. However, Janssens would soon develop his own distinct approach, often favoring larger, more open spaces and a greater sense of movement, particularly in his signature dance scenes. His training provided a solid foundation in the techniques and popular subjects of Antwerp genre painting.

Following his apprenticeship, Janssens achieved a significant professional milestone. In the guild year 1643-1644, he was admitted as a 'wijnmeester' (master by descent, typically meaning the son of an existing master) into the prestigious Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. This membership was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently, take on pupils, or sell their work legally within the city. It signified his official recognition as a qualified and independent painter within Antwerp's highly structured artistic community.

The Artistic Environment of 17th-Century Antwerp

Antwerp in the mid-17th century, when Janssens became a master, was an environment shaped by the towering legacy of the previous generation, especially Rubens and Van Dyck. While the city faced economic challenges compared to its 16th-century 'Golden Age', it remained a powerhouse of artistic production, particularly within the Southern Netherlands under Spanish Habsburg rule. The Counter-Reformation continued to fuel demand for religious art, but there was also a burgeoning market for secular subjects, including portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes.

The Guild of Saint Luke remained the central institution governing the lives of artists and artisans. It regulated training, production standards, and sales, fostering a sense of community but also competition. Artists often specialized, and collaboration was common – one painter might create the figures, another the landscape or architectural background. While specific collaborations involving Janssens are not frequently documented, the practice was endemic to the Antwerp school.

Genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, flourished in both the Northern and Southern Netherlands. In Antwerp, artists like Adriaen Brouwer and David Teniers the Younger became famous for their depictions of peasant life, taverns, and rustic festivities, often with a moralizing undertone. Janssens, alongside his teacher Van der Lamen and others like Gonzales Coques (known for elegant group portraits often called 'conversation pieces'), catered to a different segment of the market, focusing on the more refined and aristocratic aspects of social life.

'Den Danser': Specialization in Elegant Assemblies

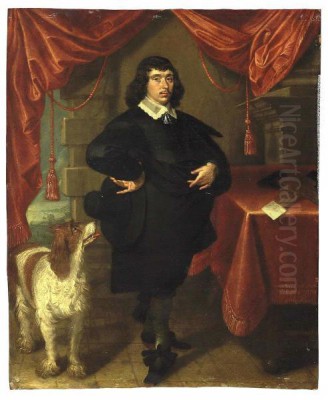

Hieronymus Janssens' enduring fame rests on his specialization, which earned him the nickname 'Den Danser'. His oeuvre is dominated by depictions of balls, dances, concerts, and garden parties, usually populated by members of the upper echelons of society. These are not the boisterous peasant kermesses painted by Teniers, but rather sophisticated affairs set in opulent surroundings. Palatial interiors with high ceilings, marble columns, checkered floors, and large windows or archways opening onto terraces or gardens are common backdrops.

His paintings capture the movement and grace of the dance, often featuring couples engaged in formal steps while onlookers converse, play music, or observe the scene. The figures are invariably dressed in the height of contemporary fashion, showcasing rich fabrics like silk and velvet, intricate lace collars, and elaborate hairstyles. Janssens paid meticulous attention to these details, adding to the sense of luxury and refinement that permeates his work.

The settings themselves are crucial. Janssens often employed strong architectural elements and perspective to create a sense of depth and grandeur, framing the human activity within an imposing, stage-like space. This theatrical quality is characteristic of the Baroque. Whether indoors or outdoors on elegant terraces, the environment underscores the status and sophisticated lifestyle of the participants. Works like Ball on the Terrace of a Palace exemplify this, combining architectural splendor with the lively, yet controlled, energy of the dance.

Artistic Style: Flemish Baroque in Genre Painting

Janssens' style is firmly rooted in the Flemish Baroque tradition, adapted to the specific demands of genre painting. Key characteristics are evident in his work. He utilized dynamic compositions, often arranging figures in flowing lines or complex groups that guide the viewer's eye through the scene. While his figures maintain an air of elegance and composure, there is often an underlying sense of movement and interaction that prevents the scenes from feeling static.

His use of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, while perhaps not as dramatic as Caravaggio or Rembrandt, plays a significant role. Light often streams in from windows or unseen sources, highlighting key figures or groups, illuminating the rich textures of fabrics, and creating contrasts that enhance the three-dimensionality of the space. This manipulation of light adds to the theatricality and visual interest of his paintings.

Janssens' color palette tends to be rich and varied, reflecting the luxurious costumes and settings. He skillfully rendered textures, from the sheen of silk dresses to the coolness of marble floors and the softness of feathered hats. His brushwork is generally refined and detailed, particularly in the rendering of figures and attire, consistent with the high finish often expected in Flemish painting for the open market. Compared to some Dutch genre painters like Jan Steen, whose scenes might be more overtly narrative or humorous, Janssens generally maintained a greater sense of decorum and elegance, focusing on the visual spectacle of the event.

Representative Works: Capturing the Spectacle

Several key works exemplify Hieronymus Janssens' style and subject matter. A Grand Ball, housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris, is a quintessential example. It depicts a large, ornate hall filled with numerous figures. In the foreground and middle ground, couples are engaged in dancing, observed by groups of elegantly dressed men and women who converse and watch the proceedings. The architectural setting is prominent, with tall columns and arches creating a majestic atmosphere. The play of light illuminates the dancers and the luxurious fabrics of their clothing, showcasing Janssens' skill in rendering detail and creating a festive, yet formal, mood.

Another significant work is Ball on the Terrace of a Palace (Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille). Dated 1658, this painting shifts the setting outdoors to an expansive palace terrace, offering a view of gardens beyond. Again, numerous figures populate the scene, some dancing, others playing music or engaging in conversation. The combination of architectural elements, landscape vistas, and the lively human activity creates a complex and engaging composition. The open-air setting allows for a brighter overall illumination compared to some interior scenes, but Janssens still uses light and shadow to model the figures and define the space.

Other works, often titled generically as Elegant Company Making Music, Figures Merrymaking in an Interior, or Garden Party, further explore these themes. A painting titled Main Courante (likely referring to a type of dance or game) shows figures in a circle, emphasizing the communal aspect of these social rituals. Across these works, the consistent elements are the focus on aristocratic leisure, the detailed rendering of fashion and setting, and the dynamic, yet graceful, arrangement of figures within a well-defined space.

Themes: Social Rituals and Courtship

Beyond the surface depiction of entertainment, Janssens' paintings touch upon themes of social ritual, status display, and courtship. The balls and gatherings he painted were important social functions where young men and women could meet, interact under watchful eyes, and form connections. The elaborate codes of dress and behavior, the formal dances, and the polite conversations were all part of the intricate social fabric of the elite. Janssens captures these rituals with a keen eye for detail.

The display of wealth and status is undeniable. The opulent settings, luxurious clothing, and leisurely pursuits all speak to the privileged world inhabited by his subjects. These paintings likely appealed to patrons who either belonged to this world or aspired to it, serving as both reflections of reality and idealized representations of sophisticated living. The presence of musicians, servants (sometimes discreetly in the background), and even pets adds layers to the social dynamics depicted.

While not typically overtly narrative in the way history paintings are, some scenes might contain subtle hints of flirtation or specific social interactions. The arrangement of figures, their gazes, and gestures can suggest underlying relationships or moments within the larger event. However, Janssens' primary focus seems to remain on the overall atmosphere of elegance and collective enjoyment rather than deep psychological exploration or complex storytelling. An exception might be the more unusual or allegorical themes, such as the reported painting of women fighting over trousers (The Struggle for the Breeches), which, if accurately attributed and interpreted, would represent a departure into comedic or satirical territory, possibly drawing on popular proverbs or moralizing traditions, akin perhaps to some works by Jan Steen or Jacob Jordaens in their more boisterous moments.

Influence and Artistic Lineage

Hieronymus Janssens' work, while specialized, had an impact. As a master in the Guild, he fulfilled his role in transmitting artistic knowledge. Records indicate he took on four pupils in 1651-1652, shortly after his marriage to Catharina van Dooren in 1650. While the names of these pupils are not always readily available in general sources, his teaching activity demonstrates his standing within the Antwerp art community. His style and subject matter likely influenced these students and potentially other contemporaries working in genre painting.

His focus on elegant gatherings in interior and exterior settings is seen as a precursor or parallel development to the 'conversation piece' genre, which gained prominence later in the 17th and particularly the 18th century, notably in England with artists like William Hogarth and Johann Zoffany, but also finding echoes in the fêtes galantes of French Rococo painters. Although geographically and chronologically distinct, the lineage of depicting refined social interaction in elegant settings can be traced back, in part, to the tradition Janssens worked within. Antoine Watteau, the great French Rococo painter known for his fêtes galantes, certainly depicted scenes of aristocratic leisure with a sensitivity that, while distinct, shares a thematic ancestor with Janssens' work.

Within Flanders, Janssens stands alongside figures like Gonzales Coques, who painted smaller-scale group portraits in elegant settings, and his own master, Christoffel van der Lamen. He differentiated himself through his emphasis on larger gatherings and the dynamic element of dance. His work offers a contrast to the peasant scenes of David Teniers the Younger or Adriaen Brouwer, showcasing the diversity within Flemish genre painting, which catered to various tastes and social strata. He represents the more aristocratic, courtly vein of the tradition.

Collaborations, Connections, and Contemporaries

The Antwerp art scene fostered collaboration. While Janssens was primarily known for his figures and overall compositions, it's possible he may have collaborated with architectural specialists or landscape painters for some of his backgrounds, although concrete evidence for specific, regular collaborators is scarce. Painters like Wilhelm Schubert van Ehrenberg or Dirck van Delen (though primarily active in the North) specialized in architectural perspectives, and figure painters often worked with them. Janssens' own skill in rendering architecture seems proficient, suggesting he may have handled many settings himself.

His direct, documented connection is with his teacher, Christoffel van der Lamen. The mention of "Pieter Jansz" and "Wild Janens" in some sources associated with the provided text is ambiguous. There were many artists named Pieter Jansz; without further context, identifying a specific connection is difficult. Pieter Janssens Elinga (1623-1682) was a Dutch painter known for interiors, a possible but unconfirmed link. "Wild Janens" might be a corruption or reference related to the landscape painter Jan Wildens (1586–1653), who collaborated extensively with Rubens and others, but a direct link to Hieronymus Janssens is not established.

His contemporaries in Antwerp included major figures like Jacob Jordaens (who outlived Rubens and Van Dyck, continuing the grand Baroque tradition), David Teniers the Younger (highly successful with peasant scenes), Gonzales Coques, and members of the Francken dynasty, such as Frans Francken the Younger (known for detailed cabinet pictures often filled with figures). These artists represent the diverse artistic production of the city during Janssens' active period.

Attribution Challenges: The Case of Victor Honoré Janssens

A recurring issue in the study of Hieronymus Janssens is the potential confusion with another artist, Victor Honoré Janssens (1658–1736). Victor Honoré was born later, primarily active in Brussels, and traveled to Italy. While he also painted historical and mythological subjects, and sometimes genre-like scenes, his style belongs to a later phase of Baroque, transitioning towards Classicism. The similarity in name has occasionally led to misattributions. Art historical scholarship generally distinguishes between the two, assigning the characteristic elegant dance and assembly scenes of the mid-17th century firmly to Hieronymus 'Den Danser'. Careful examination of style, signatures (Hieronymus often signed and dated his works, particularly between the 1640s and 1661), and provenance helps differentiate their respective oeuvres.

The provided text notes that some works attributed to Victor Honoré might actually be by Hieronymus. This reflects the ongoing process of connoisseurship and research required to clarify attributions, especially for artists with similar names or subject matter working in relative proximity of time and place. However, the core body of work associated with 'Den Danser' – the mid-century Antwerp balls and elegant companies – is securely attributed to Hieronymus Janssens.

Later Life, Reception, and Legacy

Details about Hieronymus Janssens' later life, after the period of his most frequently dated works (roughly the 1640s and 1650s), are less abundant. He married Catharina van Dooren in 1650 and is known to have taken pupils shortly after. He lived until 1693, suggesting a long career, although signed and dated works seem less common from his later decades. It's possible his style evolved, or he focused on different themes, or perhaps later works are less frequently identified or have been lost.

His paintings were clearly popular during his lifetime and afterwards. Their appeal lay in their elegance, decorative quality, and depiction of a desirable lifestyle. They found their way into significant collections relatively early. Today, his works are held by major international museums, including the Louvre in Paris, the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille, the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, the Museo del Prado in Madrid, and others, as well as appearing on the art market.

His legacy lies in his successful specialization. As 'Den Danser', he created a distinct identity and catered to a specific market niche. He remains a key figure for understanding the breadth of Flemish genre painting beyond the more commonly known peasant scenes. His work provides invaluable visual documentation of the social customs, fashion, and interiors of the mid-17th century Flemish elite, captured with the characteristic energy and decorative richness of the Baroque era.

Conclusion: The Enduring Charm of 'Den Danser'

Hieronymus Janssens stands out in 17th-century Flemish art not for grand historical narratives or profound religious statements, but for his mastery in capturing the ephemeral grace and choreographed elegance of social life. His nickname, 'Den Danser', perfectly encapsulates his artistic focus. Through his detailed and lively paintings of balls, concerts, and garden parties, he offers a glimpse into a world of aristocratic leisure, rendered with the dynamism, attention to detail, and theatrical flair characteristic of the Antwerp Baroque school.

Working in the shadow of giants like Rubens yet finding his own voice, Janssens skillfully blended the influence of his teacher, Christoffel van der Lamen, with his own penchant for movement and grand settings. His work contributed to the development of genre painting, particularly the depiction of elegant companies, and provides a valuable counterpoint to the rustic scenes of contemporaries like Teniers. Despite occasional attribution issues, his core oeuvre remains a testament to his unique talent. The enduring presence of his paintings in major museums attests to their lasting appeal, preserving the vibrant spectacle of 17th-century Flemish festivities for posterity.