Introduction: Capturing a Vanishing World

Pietro Longhi stands as one of the most distinctive and charming painters of the eighteenth-century Venetian school. Born Pietro Falca in Venice in 1702, he adopted the surname Longhi later in his career. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on grand historical narratives, religious scenes, or expansive city views (vedute), Longhi dedicated his artistic life to capturing the intimate, everyday moments of Venetian society. His small-scale genre paintings offer a unique window into the private lives, social rituals, and gentle amusements of the Venetian aristocracy and upper bourgeoisie during the Republic's final century. With a delicate touch, soft colours, and a keen eye for detail laced with subtle humour, Longhi became the foremost visual chronicler of his time and place, preserving the fleeting elegance and peculiar customs of a world on the cusp of change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Pietro Longhi's origins lie within the artisan class of Venice. His father, Alessandro Falca, was a silversmith, suggesting an early exposure to craftsmanship and design within the family home. Initially, Pietro received training from his father, likely learning the fundamentals of drawing and perhaps engraving, skills valuable in the silversmith trade. However, his aptitude for painting soon became apparent.

Seeking formal instruction, the young artist was placed under the tutelage of Antonio Balestra (1666-1740), a respected Veronese painter who had also worked in Venice and Rome. Balestra was known for his more classical style, influenced by Carlo Maratta, and represented a solid, if somewhat conservative, grounding in academic principles. While Balestra provided foundational training, a more significant influence on Longhi's development came later.

Recognizing his pupil's potential, Balestra recommended that Longhi travel to Bologna to study with Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747). This move proved pivotal. Crespi, known as "Lo Spagnuolo" (The Spaniard) for his dark palette and dramatic lighting, was a highly original artist whose work encompassed religious subjects, portraits, and, importantly for Longhi, genre scenes. Crespi's depictions of everyday life, often imbued with earthy realism and psychological insight, offered a compelling alternative to the grand manner prevalent at the time. The experience in Crespi's studio profoundly shaped Longhi's artistic direction, steering him away from the large-scale historical or religious compositions he initially attempted.

The Turn Towards Genre Painting

Upon returning to Venice, Longhi initially tried his hand at the more traditional and potentially lucrative field of history painting. Early commissions included religious works, such as the altarpiece depicting the martyrdom of St. Pellegrino for the church of San Pellegrino. He also undertook decorative projects, like the large-scale fresco depicting the Fall of the Giants (1734) for the staircase ceiling of the Palazzo Sagredo.

However, these early forays into grand-scale painting were not met with overwhelming success. Contemporary accounts suggest his handling of monumental compositions was perhaps not his strongest suit. It seems Longhi himself recognized this, or perhaps he simply found greater personal satisfaction and a more receptive market elsewhere. Influenced by his time with Crespi and likely observing the growing European taste for scenes of contemporary life, Longhi made a decisive shift in his artistic focus around the late 1730s and early 1740s.

He began producing the small, intimate cabinet pictures depicting scenes of Venetian daily life for which he would become famous. This transition marked the true beginning of his mature career and established his unique niche within the vibrant Venetian art scene. His focus moved from the epic to the everyday, from the historical to the contemporary, finding rich subject matter in the drawing rooms, coffee houses, and quiet corners of his native city.

The Venetian Context: A World of Spectacle and Intimacy

To fully appreciate Longhi's work, one must understand the unique environment of eighteenth-century Venice. While the Republic of Venice was in a state of slow political and economic decline, its reputation as a centre of pleasure, culture, and spectacle remained undimmed. The city was a magnet for wealthy tourists undertaking the Grand Tour, drawn by its unique beauty, its libertine atmosphere, and its famous Carnival season.

Life, particularly for the upper classes Longhi depicted, was a blend of public display and private ritual. The Carnival, which could last for months, saw Venetians of all classes mingling behind the anonymity of masks (bauta and moretta), frequenting theatres, opera houses, and gambling dens (ridotti). Coffee houses (caffè) became important social hubs, places for conversation, business, and discreet encounters. Private homes hosted salons, musical performances, and card games.

This backdrop of elaborate social customs, fashion, leisure, and veiled identities provided Longhi with endless inspiration. While artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712-1793) captured the breathtaking public face of Venice – its canals, squares, and ceremonies – Longhi turned his gaze inward. He focused on the human interactions within these spaces, documenting the manners, pastimes, and quiet dramas of Venetian society with an intimacy that contrasted sharply with the grand vedute of his contemporaries. Even the grand decorative schemes of Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770), filled with light and mythological figures, represented a different facet of Venetian art, focused on aristocratic splendour rather than everyday observation.

Subject Matter: Chronicling Venetian Society

Longhi's paintings, often referred to as conversazioni or conversation pieces, meticulously document the activities and environments of the Venetian elite and bourgeoisie. He rarely depicted the lowest classes, preferring the refined world of the palazzi and fashionable public spaces. His subjects are drawn from the fabric of daily existence, rendered with charm and a gentle, observational wit.

Domestic life features prominently. We see ladies receiving visitors in their boudoirs (The Visit), families engaged in music lessons (The Music Lesson), gentlemen taking instruction (The Geography Lesson), or the ritual of morning refreshment (The Morning Chocolate). These scenes offer glimpses into the private routines and social obligations that structured upper-class life. The interiors are often carefully rendered, showing contemporary furniture, décor, and objets d'art.

Public and semi-public spaces also appear frequently. Longhi painted scenes set in the ridotto, the state-controlled gambling house where masked figures tried their luck (The Ridotto). He depicted the bustling atmosphere of coffee houses and the specialized shops catering to aristocratic needs, such as the apothecary (The Apothecary) or the perfume seller (The Perfume Seller). These works capture the mingling of commerce, leisure, and social interaction that characterized Venetian public life.

The Carnival provided particularly rich material. Longhi often included figures wearing the distinctive white bauta mask and black tricorn hat, hinting at the themes of anonymity, intrigue, and social leveling associated with the festival. Even seemingly mundane events could become subjects, such as The Tooth Puller, depicting a public practitioner attracting a crowd, or the celebrated Exhibition of a Rhinoceros in Venice (1751), which documents the real-life display of Clara the rhinoceros, a famous animal that toured Europe, capturing the public's fascination with the exotic. Another recurring theme is the charlatan or quack doctor, often shown peddling dubious remedies, reflecting a gentle satire on credulity (The Charlatan).

Through these varied subjects, Longhi created a comprehensive visual record of eighteenth-century Venetian customs, fashion, and social dynamics. His focus remained consistently on human interaction, observing gestures, postures, and groupings with a playwright's eye for social nuance.

Artistic Style and Technique

Pietro Longhi developed a highly personal style perfectly suited to his subject matter. While influenced by the broader European Rococo movement, particularly in its lightness, elegance, and preference for intimate scenes, his work possesses a distinct character that sets it apart from French contemporaries like Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) or François Boucher (1703-1770). Longhi's paintings are less overtly sensual or mythological than much French Rococo art; instead, they emphasize observation, anecdote, and a quiet theatricality.

His canvases are typically small in scale, designed for private contemplation rather than public display. He employed a palette characterized by soft, luminous colours – pearly whites, pale blues, delicate pinks, and gentle yellows – applied with a refined, delicate brushstroke. His handling of light is often subtle and diffused, creating a calm, clear atmosphere that illuminates the scene without harsh contrasts. This careful modulation of light and colour contributes significantly to the gentle, harmonious mood of his paintings.

Longhi paid meticulous attention to detail, particularly in rendering fabrics, clothing, and interior furnishings. The textures of silk, lace, velvet, and polished wood are often convincingly portrayed, adding to the sense of realism and documenting the fashions of the era. This focus on surface detail aligns him with the tradition of Dutch seventeenth-century genre painters like Gerard ter Borch or Gabriel Metsu, although Longhi's touch is generally lighter and his figures less psychologically penetrating.

His figures, while accurately observed in terms of costume and social type, can sometimes appear slightly stiff or doll-like in their poses and gestures. They often interact with a degree of formality or reservedness, arranged across the shallow space of the canvas almost like actors on a stage. This slight artificiality, however, contributes to the unique charm of his work, lending it a quality of gentle caricature or a scene observed through a slightly detached, amused lens. It avoids strong emotional display, favouring subtle indications of social interaction and quiet amusement.

The motif of the mask is recurrent and significant. The bauta, covering most of the face, renders individuals anonymous and equal, reflecting a key aspect of Venetian Carnival culture. In Longhi's paintings, masks add an element of mystery, intrigue, and gentle satire, hinting at the difference between public persona and private reality. This observational, sometimes satirical, edge has led to comparisons with the English painter and printmaker William Hogarth (1697-1764), though Longhi's satire is generally much gentler and less overtly moralizing. He observes social foibles with amusement rather than condemnation. Another point of comparison in genre painting might be the French master Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), who also focused on quiet domesticity, though Chardin's style was more grounded and less focused on aristocratic elegance.

Key Representative Works

Longhi's oeuvre is remarkably consistent in theme and style, but several works stand out as particularly representative or significant:

The Concert (c. 1741, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice): One of his early successes in the genre format, this painting depicts a small group gathered for an intimate musical performance in a domestic setting. It exemplifies his ability to capture the atmosphere of refined leisure and social gathering, with careful attention to the details of dress and interior decoration.

The Visit (c. 1746, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): Part of a series likely commissioned by the Pisani family, this work shows a lady receiving a morning visitor while still in her boudoir. It highlights the social rituals governing interactions between the sexes and the blend of intimacy and formality in aristocratic life.

The Letter (c. 1746, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): Also from the Pisani series, this painting depicts a moment of quiet communication, perhaps hinting at a secret correspondence. Like many of Longhi's works, it invites narrative speculation while maintaining a degree of ambiguity.

The Temptation (c. 1746, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): Another piece from the Met's series, showing a masked gentleman offering something to a lady, possibly during Carnival time. The masks add a layer of intrigue and potential impropriety.

The Meeting (c. 1746, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): Completing the quartet at the Met, this scene portrays a formal encounter between a masked couple, emphasizing the choreographed nature of social interactions.

Exhibition of a Rhinoceros in Venice (1751, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice / National Gallery, London): This famous painting documents a real event – the display of Clara the rhinoceros during Carnival. It captures the curiosity of the masked crowd gathered to view the exotic animal, showcasing Longhi's ability to record specific contemporary events with his characteristic charm and detail.

The Tooth Puller (c. 1750, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan): A scene of popular life, depicting a travelling dentist extracting a tooth before a small crowd. It shows Longhi's occasional foray into depicting less aristocratic subjects, capturing the blend of spectacle and everyday hardship with gentle humour.

The Charlatan (c. 1757, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice): This work depicts a quack doctor promoting his wares to a group of onlookers, some masked. It offers a light satirical commentary on popular credulity and the theatricality of street life.

The Dance Lesson (c. 1741, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice): An elegant interior scene showing young aristocrats learning the formal steps of a dance, highlighting the importance of social graces in their upbringing.

The Morning Chocolate (c. 1775-80, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice): A later work depicting the intimate morning ritual of a lady taking chocolate, attended by her maid and a male visitor (perhaps an abbé). It shows the continuity of his themes and style into his later career.

These works, among many others, solidify Longhi's reputation as a master observer of his society, capturing its rituals, amusements, and underlying dynamics with unparalleled intimacy and grace.

Longhi and His Contemporaries

Pietro Longhi occupied a unique position within the Venetian art world. While Venice boasted major figures like the aforementioned Canaletto, Guardi, and Tiepolo, Longhi's focus on intimate genre scenes set him apart. Canaletto and Guardi excelled in vedute, capturing the city's architecture and atmosphere on a grand scale, often for the Grand Tour market. Tiepolo, along with artists like Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta (1683-1754), continued the tradition of large-scale decorative painting for palaces and churches, filled with dynamic figures and brilliant light.

Longhi's closest parallel in spirit, though not in medium, was the playwright Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793). Both Longhi and Goldoni were keen observers of Venetian society, and both depicted the manners, conversations, and intrigues of the middle and upper classes with realism and humour. Goldoni reformed Italian comedy by moving away from the stock characters of the Commedia dell'arte towards more naturalistic portrayals of contemporary life, much as Longhi moved away from historical subjects to depict the world around him. Contemporaries recognized this affinity; Goldoni himself praised Longhi, effectively calling him a painter who did with his brush what Goldoni did with his pen.

While distinct from the vedutisti, Longhi occasionally incorporated recognizable Venetian settings, but his primary interest was always the human element. Compared to the celebrated pastellist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), who achieved international fame with her elegant portraits, Longhi's focus was broader, encompassing social situations rather than individual likenesses, although he did produce some portraits. His teacher, Crespi, remained an influence, particularly in the choice of genre subjects, but Longhi developed a lighter palette and a more refined, less earthy style than his Bolognese master.

His relationship with the official art establishment was solid. He was elected to the Venetian Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia) in 1756, a mark of recognition from his peers. From 1763, he served as a teacher of drawing at the Academy, indicating respect for his technical skills.

Patronage and Reception

Longhi's paintings found a ready market among the Venetian nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie whose lives he depicted. Families such as the Grimani, Pisani (who commissioned the series now in the Metropolitan Museum), Sagredo (for whom he painted the early Fall of the Giants), Emo, Rezzonico, and Querini were among his patrons. The small scale and intimate subject matter of his works made them ideally suited for the private apartments (appartamenti) of Venetian palaces, where they could be appreciated up close.

His popularity in Venice was considerable during his lifetime. His paintings offered patrons a charming reflection of their own world, rendered with elegance and a gentle humour that affirmed their social standing and lifestyle. He often produced multiple versions or variations of popular compositions, suggesting a steady demand for his work.

However, his fame did not extend widely beyond Venice and the Veneto region during the eighteenth century. Unlike Canaletto, whose views were eagerly collected by British Grand Tourists, or Tiepolo and Carriera, who received commissions from across Europe, Longhi remained a more local phenomenon. His name was little known in places like Russia or even France, despite stylistic affinities with French Rococo genre scenes. His art was perhaps too specifically Venetian, too focused on the nuances of a particular society, to achieve broad international appeal at the time.

Later Life and Legacy

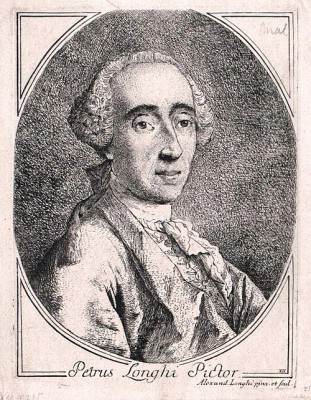

Pietro Longhi continued to paint actively into his later years, maintaining his characteristic style and subject matter. His son, Alessandro Longhi (1733-1813), followed him into the profession, becoming a successful portrait painter in his own right and also a member of the Venetian Academy. Alessandro is also known for his biographical work, Compendio delle vite de' pittori veneziani istorici più rinomati del presente secolo (Compendium of the Lives of the Most Renowned Historical Venetian Painters of the Present Century), published in 1762, which provides valuable information about his father and other contemporaries, though it focuses more on history painters.

Pietro Longhi died in Venice on May 8, 1785, just a few years before the fall of the Venetian Republic (1797) whose final decades he had so meticulously documented. After his death, and with the decline of Venice itself, his reputation faded somewhat. The nineteenth century, with its preference for Neoclassicism and Romanticism, paid less attention to his gentle Rococo charm.

However, a reappraisal began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Critics and art historians rediscovered his work, recognizing its unique value not only for its artistic merit but also as an invaluable historical document. Longhi came to be seen as the quintessential visual chronicler of eighteenth-century Venice, capturing the atmosphere of a society devoted to pleasure, politeness, and spectacle in the twilight years of its existence. His paintings offer insights into the social customs, fashion, leisure activities, and intimate moments of a lost world.

Today, Pietro Longhi is celebrated as a master of genre painting, admired for his delicate technique, his subtle use of colour and light, his keen powers of observation, and his gentle, pervasive humour. He holds a secure place in art history as the artist who, more than any other, captured the private face of eighteenth-century Venice.

Conclusion: The Intimate Eye of Venice

Pietro Longhi's contribution to art history lies in his intimate and insightful portrayal of eighteenth-century Venetian life. Forsaking the grand narratives and expansive vistas favoured by many contemporaries, he focused his lens on the everyday interactions, social rituals, and quiet amusements of the city's upper classes. His small, jewel-like canvases, rendered in soft colours and with delicate precision, capture the unique blend of elegance, formality, and gentle hedonism that characterized Venice in its final decades as an independent republic.

Through his keen observation and subtle humour, Longhi created a body of work that is both artistically charming and historically invaluable. He documented a specific society at a specific moment, preserving its fashions, manners, and pastimes for posterity. While perhaps less technically dazzling than Tiepolo or less internationally renowned in his time than Canaletto, Longhi offers something unique: a sustained, intimate, and affectionate gaze into the heart of Venetian social life. He remains the preeminent visual chronicler of his world, the painter who captured the quiet conversations, the masked encounters, and the fleeting moments of grace in the drawing rooms and coffee houses of a captivating and vanishing Venice.