Hugo Kotschenreiter stands as a notable figure within the Munich School of painting, primarily recognized for his engaging and often humorous depictions of everyday life in Upper Bavaria during the late 19th century. Born in Hof, Bavaria, in 1854 and passing away in Munich in 1908, Kotschenreiter's artistic journey reflects a transition common among artists of his time, moving from architectural studies to the expressive potential of painting, ultimately carving a niche for himself through detailed and characterful genre scenes.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Kotschenreiter's initial foray into the arts was not through painting but architecture. He began his studies at the Nuremberg School of Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule Nürnberg), an institution known for fostering technical skill and design principles. This early training likely instilled in him a sense of structure and attention to detail that would later become evident in the carefully rendered interiors and compositions of his paintings. However, the allure of pictorial representation eventually led him away from architectural plans.

Seeking a more painterly path, Kotschenreiter enrolled in the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). During the latter half of the 19th century, Munich was a major European art center, rivaling Paris in importance, particularly for realist and historical painting. The Academy was the heart of this artistic ferment, attracting students from across Germany and beyond. Its emphasis on rigorous academic training, drawing from life, and mastering technique provided a solid foundation for aspiring artists.

Mentorship under Munich Masters

At the Munich Academy, Kotschenreiter had the invaluable opportunity to study under two prominent figures of the era: Karl von Piloty (1826-1886) and Alexander von Wagner (1838-1919). Both were leading exponents of history painting, a genre highly esteemed in academic circles. Piloty, in particular, was a towering figure whose influence shaped a generation of artists. He was known for his large-scale historical canvases, characterized by dramatic compositions, meticulous detail, and a rich, often dark, palette.

Piloty's teaching emphasized historical accuracy, psychological depth in figures, and theatrical staging. While Kotschenreiter would ultimately focus on genre scenes rather than grand historical narratives, the principles learned under Piloty – careful observation, strong draftsmanship, and the ability to construct a narrative within a scene – undoubtedly informed his later work. Many famous artists emerged from Piloty's circle, including Franz von Lenbach, known for his portraits of prominent figures like Bismarck, and Hans Makart, whose opulent style defined an era in Vienna.

Alexander von Wagner, a Hungarian-born painter who became a professor at the Munich Academy, also specialized in history painting, often depicting dramatic scenes from Hungarian history, as well as genre subjects. Studying under both Piloty and Wagner exposed Kotschenreiter to the prevailing academic standards of realism, technical proficiency, and narrative clarity. This training provided him with the skills to render figures, costumes, and settings with convincing detail, even when applied to more intimate, everyday subjects.

The Munich School and the Rise of Genre Painting

Hugo Kotschenreiter's work fits comfortably within the broader context of the Munich School. This term generally refers to the style of painting that flourished in Munich from the mid-19th century onwards, characterized by a commitment to realism, often infused with a painterly technique and a tendency towards darker tonalities, influenced by Dutch Old Masters. While history painting was dominant initially, genre painting – the depiction of scenes from everyday life – gained immense popularity.

Genre painting offered artists a way to connect with a broader audience, depicting relatable scenes, often with sentimental or humorous undertones. Scenes of rural life, particularly from the picturesque Bavarian Alps and villages, became a favorite subject. Artists like Franz Defregger (1835-1921), another prominent Munich painter, specialized in Tyrolean and Bavarian folk life, often portraying historical peasant scenes with a strong narrative element. Kotschenreiter shared this interest in regional culture but often brought a lighter, more explicitly humorous touch to his subjects.

Another contemporary known for genre scenes, albeit often focused on monastic life depicted with humor, was Eduard von Grützner (1846-1925). While their subjects differed, both Grützner and Kotschenreiter catered to a taste for anecdotal, character-driven paintings that were both technically accomplished and easily understood. This stood somewhat in contrast to the more profound, unvarnished realism pursued by artists associated with the circle around Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), such as Wilhelm Trübner, whose focus was often on capturing the truth of appearance with less emphasis on narrative anecdote.

Chronicling Upper Bavarian Folk Life

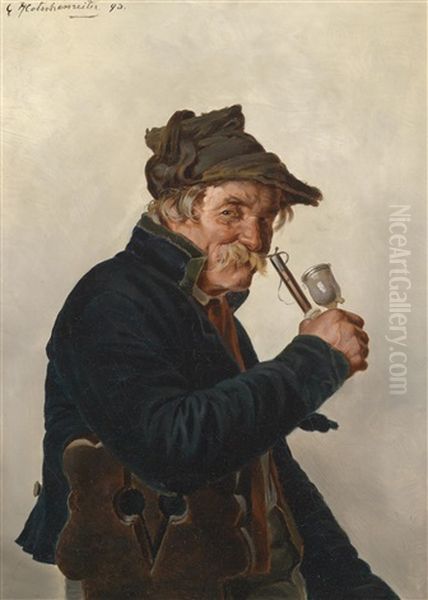

Kotschenreiter became particularly known for his humorous and insightful portrayals of Upper Bavarian folk life. His paintings often capture moments of social interaction, quiet contemplation, or gentle comedy within rustic interiors. He excelled at depicting the details of traditional clothing, furniture, and domestic settings, grounding his scenes in a specific cultural milieu. The term "humorous" suggests his work avoided overly sentimentalizing or dramatizing peasant life, instead finding amusement in everyday situations and human foibles.

His works often feature expressive characters, their personalities conveyed through posture, facial expression, and interaction. The "fine coloring" noted in descriptions of his work suggests a skillful use of palette to create atmosphere and enhance the realism of the scene, perhaps moving beyond the darker tones sometimes associated with the earlier Munich School. His background in architecture may have contributed to his ability to render interior spaces convincingly, providing detailed and authentic settings for his figures.

Two works specifically mentioned as representative are Pfeifenraucher (Pipe Smoker) and Bäuerlicher Disput (Peasant Dispute or Argument). These titles evoke typical genre subjects: the solitary figure enjoying a simple pleasure, and a more animated scene of discussion or disagreement among villagers. Such paintings likely showcased Kotschenreiter's skill in character study and narrative composition, capturing moments that were both specific to Bavarian culture and universally relatable.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Like many artists based in Munich, Kotschenreiter regularly exhibited his work at the Munich Glaspalast (Glass Palace). This vast iron and glass exhibition hall, built in 1854, was the primary venue for the city's annual international art exhibitions. Participating in these shows was crucial for an artist's visibility and reputation. The Glaspalast exhibitions attracted huge crowds and showcased a wide range of contemporary art from Germany and abroad, making it a central hub of the European art world until its tragic destruction by fire in 1931.

Kotschenreiter's participation was not limited to Munich. He also exhibited his works in Berlin and Vienna, the other major art centers of the German-speaking world. Exhibiting in these capital cities would have exposed his work to different audiences and critics, indicating a degree of success and recognition beyond his immediate Bavarian context. Berlin, with its growing Secession movement led by artists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935), and Vienna, home to Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and the Vienna Secession, were developing distinct artistic identities, often challenging the academic traditions upheld in Munich. Kotschenreiter's participation in exhibitions there suggests his genre scenes found favor even amidst these evolving artistic landscapes, likely in the more traditional venues like the Künstlerhaus societies.

The Unseen Works: Interiors and Portraits

Interestingly, it is noted that while Kotschenreiter painted interiors and portraits characterized by elegance and technical skill, these works were apparently never publicly exhibited during his lifetime. This raises intriguing questions. Perhaps these were more private endeavors, studies undertaken for personal satisfaction or technical practice. They might have been commissioned portraits intended only for the sitters and their families.

Alternatively, Kotschenreiter might have considered his genre scenes of Bavarian life to be his primary public artistic identity, the works most likely to find favor with critics and buyers at the major exhibitions. The market for humorous and relatable genre scenes was strong, and he may have chosen to focus his public efforts on this successful niche. The unexhibited works, potentially different in style or subject, remain a less understood aspect of his oeuvre, hinting at a broader artistic range than his public reputation might suggest.

Style, Technique, and Context

Hugo Kotschenreiter's style can be summarized as a form of detailed realism applied to genre subjects, infused with humor and careful observation of regional culture. His training under history painters provided him with strong technical foundations in drawing, composition, and rendering textures and details. His focus on Upper Bavarian life placed him firmly within a popular trend in 19th-century German art, yet his humorous approach offered a distinct perspective.

His work represents a continuation of the academic traditions fostered in Munich, emphasizing narrative clarity and skillful execution. He operated during a period of significant artistic change. While he maintained a broadly realist approach, younger generations were exploring new directions. In Munich itself, figures like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) were moving towards Symbolism and Jugendstil. Elsewhere, German artists like Lovis Corinth (1858-1925) and Max Slevogt (1868-1932) were embracing Impressionist techniques and a bolder, more modern sensibility. Kotschenreiter's art, therefore, represents a successful practice within the established late 19th-century mainstream, rather than the emerging avant-garde. His detailed, narrative style also finds echoes in the work of earlier German genre painters like Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885), known for his charming and often humorous depictions of Biedermeier life.

Legacy and Place in Art History

Hugo Kotschenreiter may not be as widely recognized today as his famous teachers like Piloty, or contemporaries who broke new ground like Leibl or the German Impressionists. However, his contribution lies in his skillful and engaging documentation of a specific time and place – the rural culture of Upper Bavaria at the turn of the 20th century. His paintings offer valuable visual records of traditions, costumes, and social interactions, presented with a characteristic warmth and humor.

He stands as a competent and appealing representative of the Munich School's genre painting tradition. His work found appreciation during his lifetime, evidenced by his regular participation in major exhibitions. While perhaps overshadowed by artists with grander ambitions or more revolutionary styles, Kotschenreiter successfully captured a particular facet of German life, creating works that were technically proficient, accessible, and enduringly charming. His paintings remain appreciated for their narrative detail, character portrayal, and affectionate, humorous glimpse into a bygone world. He exemplifies the many talented artists who contributed to the rich tapestry of late 19th-century European art by focusing on the specific character of their own region.