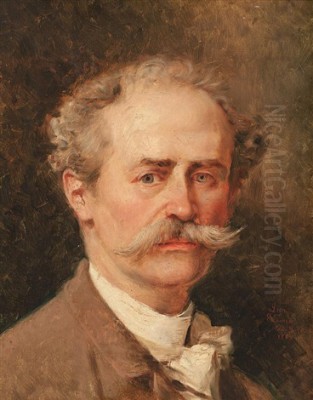

Ignacio de León y Escosura (1834-1901) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art. A Spanish painter of considerable talent and ambition, he carved a distinct niche for himself primarily through his meticulously detailed historical genre scenes, often evoking the splendors and intrigues of 16th and 17th-century European courts and aristocratic life. Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Escosura was an avid and knowledgeable collector of antiques and objets d'art, a passion that deeply informed his artistic practice and contributed to the rich, authentic atmosphere of his canvases. Active predominantly in Paris, the epicenter of the art world during his era, Escosura navigated the complex currents of artistic taste, patronage, and the burgeoning international art market, leaving behind a body of work and a collection that continue to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Spain

Born in Oviedo, Asturias, Spain, in 1834, Ignacio de León y Escosura's artistic inclinations emerged in a country with a rich visual heritage. Spain, the land of Velázquez, Goya, and Murillo, provided a potent backdrop for any aspiring artist. Escosura's formal artistic training began under the tutelage of Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz (1815-1894), a towering figure in Spanish art of the period. Madrazo, director of the Prado Museum and court painter to Queen Isabella II, was a leading exponent of Romanticism and later, a more academic realism, particularly renowned for his elegant portraiture and historical compositions.

Studying with Madrazo at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid would have exposed Escosura to a rigorous academic curriculum, emphasizing drawing from the antique, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters. Madrazo's own sophisticated style, his connections to the Spanish aristocracy, and his understanding of the broader European art scene undoubtedly shaped Escosura's early development. This period laid the foundation for Escosura's technical proficiency and his burgeoning interest in historical subjects, a genre that Madrazo himself excelled in. The influence of other Spanish masters, such as the detailed genre scenes of Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (1817-1870), who often evoked Goya, might also have played a role in shaping his early artistic vision.

The Parisian Nexus and International Development

Like many ambitious artists of his generation, Escosura recognized that Paris was the undisputed capital of the 19th-century art world. He eventually made his way to the French city, seeking to further hone his skills and establish his reputation on an international stage. In Paris, he continued his studies, notably under the celebrated French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904). Gérôme was a master of historical painting, Orientalist scenes, and meticulously rendered detail, known for his polished technique and dramatic compositions.

The tutelage under Gérôme would have reinforced Escosura's inclination towards historical accuracy and narrative clarity. Gérôme's studio was a hub for aspiring artists from across Europe and America, and the emphasis on historical research, costume, and setting was paramount. This environment would have perfectly suited Escosura's own developing interests. It was in Paris that Escosura truly flourished, developing his signature style of "tableaux de genre" or historical genre paintings, which often depicted intimate scenes from past centuries, filled with sumptuously dressed figures, antique furnishings, and a palpable sense of historical atmosphere. He became part of a vibrant community of Spanish artists in Paris, including figures like Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Federico's son and Escosura's contemporary) and the brilliant, though tragically short-lived, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1838-1874), whose dazzling technique and vibrant historical scenes set a new standard for Spanish painters abroad.

The Painter of History and Interiors

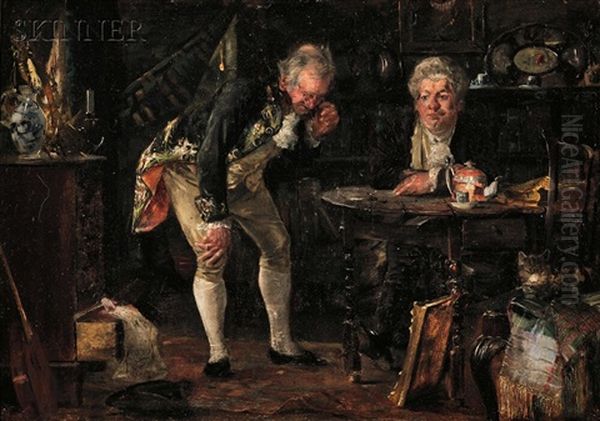

Escosura's artistic output largely centered on historical genre scenes, meticulously recreating moments from the 16th and 17th centuries. These were not grand historical narratives in the tradition of Jacques-Louis David, but rather more intimate, anecdotal scenes – a cardinal in his study, a clandestine meeting, a leisurely moment in an aristocratic household, or a gathering of connoisseurs. His paintings are characterized by their rich coloration, precise draughtsmanship, and an almost obsessive attention to the details of costume, furniture, textiles, and decorative objects.

This focus on material culture was no accident. Escosura was a passionate collector, and his studio was reportedly filled with antique furniture, tapestries, armor, weapons, and various objets d'art from the periods he depicted. These items often served as props in his paintings, lending them an air of authenticity and visual richness that appealed to the tastes of 19th-century collectors. His works can be seen as a form of "cabinet picture," small to medium-sized paintings intended for the private collections of the wealthy bourgeoisie and aristocracy, who appreciated their historical charm and technical finesse. In this, his work shared affinities with French painters like Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), who was renowned for his incredibly detailed small-scale historical and military scenes.

Representative Works: Capturing Moments in Time

Among Escosura's notable works, Día de Fiesta (Festival Day), painted in 1869, stands out. This painting is considered a significant example of Asturian folkloric style, showcasing his ability to capture local customs and traditions with vibrancy and detail. It demonstrates a connection to his Spanish roots, even as he established himself in the more cosmopolitan Parisian art scene. The work likely depicts a regional celebration, with figures in traditional attire, reflecting an interest in ethnography and local color that was part of the broader Romantic and Realist movements.

Another important work, Dos estudios de caballeros y autoportret (Two Studies of Gentlemen and Self-Portrait) from 1882, highlights his skill in portraiture and his continued engagement with historical personae. The inclusion of a self-portrait within a historical context suggests the artist's deep immersion in the worlds he recreated. His paintings often featured figures in elaborate historical dress, engaged in quiet activities that allowed for the detailed depiction of their surroundings. Titles such as The Connoisseurs, A Visit to the Studio, or scenes set in royal antechambers were typical, allowing him to showcase both his narrative skill and his collection of historical artifacts. These works appealed to a clientele fascinated by the past, offering a romanticized glimpse into earlier eras.

The Avid Collector and Connoisseur

Escosura's identity as an artist was inextricably linked with his role as a collector and connoisseur. His passion for acquiring historical artifacts was not merely a hobby but an integral part of his artistic process and public persona. He amassed a significant collection of 16th and 17th-century art and decorative objects, including furniture, textiles, arms and armor, ceramics, and metalwork. These items were not just studio props; they were objects of study and sources of inspiration, allowing him to imbue his historical scenes with a high degree of verisimilitude.

His collection was well-known, and parts of it were eventually transferred to his hometown of Oviedo, forming the basis of what would become the Galleria Parmeggiani. This act demonstrates his desire to share his passion and to contribute to the cultural heritage of his native region. The act of collecting in the 19th century was often tied to notions of taste, scholarship, and social status. For an artist like Escosura, a rich collection also served as a testament to his deep understanding of the historical periods he depicted, enhancing his credibility and appeal to patrons. His expertise extended to being an antique dealer, further blurring the lines between his artistic practice and his connoisseurship.

International Recognition and Exhibitions

Escosura actively sought to promote his work on the international stage, participating in numerous exhibitions. His paintings were first shown in the United States in 1876, likely as part of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, an event that introduced many European artists to American audiences. This marked the beginning of his engagement with the burgeoning American art market.

He also exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in London in 1874 and the Berlin Exhibition in 1886. A significant moment in his career was his role as the Spanish art representative at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. This prestigious appointment underscored his standing within the Spanish art establishment and provided a major platform to showcase his work, and that of his compatriots, to a global audience. These international exhibitions were crucial for artists in the 19th century, offering opportunities for sales, critical recognition, and the acquisition of medals and honors. Escosura's participation indicates his ambition and his success in navigating these competitive arenas. Other Spanish artists who found success in these international venues included Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923), though Sorolla's style was markedly different, focusing on light-filled impressionistic scenes.

Navigating the Art Market: Dealers and Patrons

To succeed in the 19th-century art world, artists often relied on relationships with influential art dealers. Escosura was associated with the prominent Parisian firm Goupil & Cie. Founded by Adolphe Goupil, this gallery and print publishing house was a dominant force in the international art market, representing a wide range of artists, including academic masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme (Escosura's teacher), William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), and Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), as well as artists with more modern sensibilities. Goupil's extensive network of branches in London, Brussels, The Hague, Berlin, Vienna, and New York provided artists with unparalleled access to collectors across Europe and America.

Escosura's connection with Goupil & Cie would have been instrumental in disseminating his work, both through the sale of original paintings and potentially through the production of reproductions, which Goupil famously popularized. In the United States, Escosura also collaborated with the dealer Roland F. Knoedler, whose eponymous gallery (M. Knoedler & Co.) became a major conduit for European art entering American collections. These dealer relationships were vital for marketing, sales, and building an artist's international reputation. Escosura's ability to cultivate these connections speaks to his business acumen as well as his artistic appeal.

The American Connection

The United States, with its rapidly growing class of wealthy industrialists and financiers, became an increasingly important market for European artists in the latter half of the 19th century. Escosura's works found favor with American collectors who appreciated their historical themes, meticulous craftsmanship, and European sophistication. His paintings were featured in auctions in cities like New York and New Orleans. For instance, records show his works being sold at auctions such as those held at Clinton Hall in New York.

The appeal of historical genre painting to American collectors lay in its ability to evoke a sense of history and cultural refinement, often lacking in the newer American society. Artists like Escosura offered a window into the perceived romance and elegance of Old World Europe. His success in the American market was part of a broader trend that saw European academic and historical painters, such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) with his scenes of classical antiquity, or Jehan Georges Vibert (1840-1902) with his satirical depictions of cardinals, achieve considerable popularity and financial success in the United States.

Personal Life and the Parmeggiani Connection

Escosura's personal life also intertwined with his artistic and collecting pursuits. He married Blanche Marcy, who was the proprietor of an antique shop in Paris. This union undoubtedly facilitated his access to antiques and further immersed him in the world of collecting and dealing. The Marcy workshop in Paris was known for producing high-quality metalwork, often in historical styles, and items from this workshop were part of Escosura's collection.

A fascinating and somewhat enigmatic chapter in Escosura's life involves his relationship with Luigi Parmeggiani (1860-1945). Parmeggiani, an Italian anarchist who later reinvented himself as a prominent antique dealer and collector, reportedly met Escosura in London, where Escosura had sought refuge for a time, possibly due to involvement in political intrigues in Italy. Parmeggiani became closely associated with Escosura and the Marcy collection. He eventually established a gallery in London that showcased Escosura's historical paintings, often recreating the painted scenes with actual costumes, props, and furniture from the collection.

Later, Parmeggiani moved a significant portion of the Escosura-Marcy collection to Reggio Emilia, Italy, where it formed the core of the Galleria Parmeggiani. This museum, housed in a distinctive neo-Gothic building designed by Parmeggiani himself, remains a unique repository of 19th-century collecting taste, featuring paintings, furniture, textiles, arms, and goldsmith works, many of which are linked to Escosura and the Marcy atelier. This connection highlights the complex interplay between art creation, collecting, dealing, and museum formation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Artistic Style Revisited: Romanticism and Realism

Escosura's artistic style can be situated within the broader currents of 19th-century academic art, which blended elements of Romanticism and Realism. His choice of historical subjects, often imbued with a sense of nostalgia and drama, aligns with Romantic sensibilities. However, his meticulous attention to detail, his efforts to achieve historical accuracy in costume and setting, and his polished technique reflect the prevailing academic emphasis on realism and fine craftsmanship.

His paintings are characterized by a careful arrangement of figures and objects within well-defined interior spaces. The lighting is often controlled, highlighting key figures or sumptuous details of fabric and metalwork. While his contemporary, Francisco Domingo Marqués (1842-1920), another Spanish painter of historical genre scenes, often displayed a more flamboyant brushwork reminiscent of Fortuny, Escosura generally maintained a smoother, more finished surface, akin to that of Gérôme or Meissonier. His work provided a visual escape for his audience, transporting them to meticulously reconstructed pasts, filled with elegance, intrigue, and the allure of bygone eras. He was less concerned with the grand, moralizing narratives of earlier history painters and more focused on the anecdotal, the picturesque, and the evocative power of historical settings.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Despite his success, Escosura's career was not without its complexities and, according to some accounts, controversies. The line between authentic antique, skillful reproduction, and outright forgery was sometimes blurred in the fervent 19th-century market for historical artifacts. Given Escosura's deep involvement in collecting and dealing, and the activities of the Marcy workshop which produced items in historical styles, questions have occasionally arisen regarding the precise nature and provenance of some pieces associated with his collection.

Some scholars have suggested that certain items presented as original antiques might have been later creations or "pastiches" – works created in the style of an earlier period. This was not uncommon in the 19th century, when the demand for historical objects sometimes outstripped supply, and workshops catered to this demand. Such issues, however, primarily concern his activities as a collector and dealer rather than directly impugning the quality of his paintings, which were clearly presented as contemporary creations in a historical style. His paintings themselves were generally well-received for their technical skill and charming subject matter, fitting comfortably within the accepted tastes of the Salon and the preferences of bourgeois collectors. The critical evaluation of such historical genre painting has fluctuated over time, with its popularity waning with the rise of Modernism, but there has been a renewed scholarly interest in 19th-century academic art in recent decades.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Ignacio de León y Escosura continued to paint and collect throughout his life, maintaining his studio in Paris and his connections with the international art world. He passed away in 1901 in Toledo, Spain, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a complex legacy as both a creator and a connoisseur.

His primary legacy lies in his historical genre paintings, which offer a window into the tastes and preoccupations of his era. These works, found in museums and private collections in Europe and the Americas, are valued for their craftsmanship, their evocative power, and their detailed reconstruction of historical interiors and costumes. Artists like José Benlliure y Gil (1855-1937) and José Villegas Cordero (1844-1921), also Spanish, continued the tradition of historical and genre painting with international success, though often with different stylistic emphases.

Beyond his paintings, Escosura's activities as a collector, and the subsequent history of his collection through Luigi Parmeggiani, contribute to our understanding of 19th-century collecting practices and the formation of museum collections. The Galleria Parmeggiani in Reggio Emilia stands as a testament to this aspect of his life, preserving a unique assemblage of art and artifacts that reflects the eclectic and historicizing tastes of the period. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his avant-garde contemporaries like Édouard Manet or Claude Monet, Escosura played a significant role within the academic tradition, catering to and shaping the artistic preferences of a broad international clientele.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Figure in 19th-Century Art

Ignacio de León y Escosura was a multifaceted artistic personality of the 19th century. As a painter, he excelled in the creation of meticulously detailed and richly atmospheric historical genre scenes, transporting viewers to the European courts and aristocratic interiors of centuries past. His technical skill, honed under masters like Federico de Madrazo and Jean-Léon Gérôme, was undeniable, and his works found favor with collectors on both sides of the Atlantic.

Simultaneously, his passion for collecting antiques and objets d'art deeply informed his artistic vision and practice, lending an air of authenticity and opulence to his canvases. His involvement in the art market, both as an artist and as a dealer, and his connections with prominent galleries like Goupil & Cie and Knoedler, highlight his astute understanding of the mechanisms of the 19th-century art world. The story of his collection, particularly its association with Luigi Parmeggiani and its eventual enshrinement in a public museum, adds another layer to his intriguing biography. Ignacio de León y Escosura remains a compelling figure, representative of a significant strand of 19th-century European art that valued historical narrative, technical polish, and the evocative power of the past.