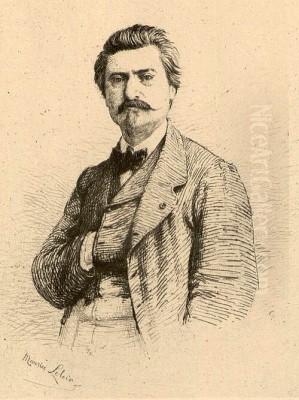

Isidore Alexandre Augustin Pils (1813–1875) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century French academic painting. Born into a period of artistic and political transition, Pils navigated the currents of Neoclassicism's legacy, the rise of Romanticism, and the eventual emergence of Realism and Impressionism. His career, deeply rooted in the academic tradition fostered by the École des Beaux-Arts, is primarily characterized by his large-scale history paintings, initially focusing on religious subjects before shifting decisively towards military themes, particularly those documenting the exploits and daily life of the French army during the Second Empire under Napoleon III. A recipient of the prestigious Prix de Rome and later a respected professor and member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Pils embodied the official artistic establishment of his time, creating works that resonated with contemporary tastes for historical grandeur, patriotic sentiment, and detailed realism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Isidore Pils was born in Paris on July 19, 1813. His background was modest yet directly connected to the military world that would later dominate his art; his father, François Pils, was a soldier. This familial connection likely provided an early, intimate perspective on military life, influencing his later artistic choices. His formal artistic education began at the relatively young age of twelve, when he entered the studio of Guillaume Guillon-Lethière (1760–1832). Lethière, himself a successful history painter who had served as Director of the French Academy in Rome, represented the Neoclassical tradition, albeit with a more dramatic flair than seen in the work of Jacques-Louis David.

Pils studied under Lethière for four years, absorbing the fundamentals of academic drawing, composition, and historical subject matter. This foundational training was crucial for any aspiring artist aiming for success within the established French art system. Following his time with Lethière, Pils sought to further his education at the pinnacle of French artistic instruction, the École des Beaux-Arts.

In 1831, Pils successfully entered the École des Beaux-Arts, joining the studio of François-Édouard Picot (1786–1868). Picot was another prominent academic painter, known for his historical, mythological, and religious works, as well as portraits. He was a respected teacher whose students included other notable artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, who would become leading figures of later 19th-century academicism. Studying under Picot further solidified Pils's grounding in the academic method, emphasizing meticulous draftsmanship, idealized forms derived from classical sculpture and Renaissance masters, and the composition of complex narrative scenes.

The Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

The ultimate goal for ambitious students at the École des Beaux-Arts was winning the Prix de Rome. This prestigious state-sponsored prize granted the winner a funded residency at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the Villa Medici. It was an unparalleled opportunity to study classical antiquity and the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance firsthand, considered essential for the development of a history painter. Pils competed for the prize, and in 1838, his efforts were rewarded.

He won the Prix de Rome in the historical painting category for his work Saint Peter Healing the Lame Man at the Door of the Temple. This painting, typical of the competition's requirements, demonstrated his mastery of academic principles: a clear narrative drawn from the Bible, a complex multi-figure composition, anatomically correct figures rendered with precision, and a suitably grand and serious tone. The subject, depicting an act of miraculous healing, allowed for dramatic gestures and emotional expressions, showcasing Pils's ability to handle complex historical and religious narratives.

Winning the prize enabled Pils to travel to Rome, where he resided at the Villa Medici for several years (sources vary between three and five years). This period was transformative. He immersed himself in the art of the past, studying ancient Roman sculpture and architecture, and the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio. As was customary for pensioners of the Academy, he also traveled within Italy, visiting key artistic centers such as Naples, Florence, and Venice. These travels broadened his artistic horizons, exposing him to different schools of Italian painting and diverse landscapes and local customs, which sometimes found their way into genre studies produced during his stay.

Early Career and Religious Themes

Upon his return to Paris from Italy in the early 1840s, Pils began establishing his career, exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon, the official, juried exhibition crucial for artistic recognition and patronage. His initial works largely continued in the vein expected of a Prix de Rome laureate, focusing predominantly on religious subjects drawn from the Bible and the lives of saints. These paintings allowed him to display the skills honed in Italy – grand compositions, idealized figures, and a serious, often pious, sentiment.

Examples of his work from this period include paintings like Christ Preaching in the Synagogue and Death of St. Mary Magdalene. These subjects were popular choices within the academic tradition and appealed to both state and private patrons, including the Church. Religious painting was still highly regarded, carrying moral weight and historical prestige. Pils's approach was aligned with the prevailing academic style, which sought clarity, dignity, and emotional restraint, often influenced by the Nazarene movement or the purist tendencies seen in contemporaries like Hippolyte Flandrin (1809–1864), another student of Ingres known for his religious murals.

While competent and well-received within academic circles, these early religious works did not necessarily set Pils dramatically apart from other skilled history painters of his generation, such as Ary Scheffer (1795–1858), who also enjoyed considerable success with religious and literary themes rendered in a more Romantic, sentimental style. However, Pils's solid grounding in historical composition and large-scale figure painting laid the essential groundwork for the next major phase of his career.

Shift Towards Military Painting: The Crimean War

A significant turning point in Pils's artistic trajectory occurred in the mid-1850s with the outbreak of the Crimean War (1853–1856). France, under Emperor Napoleon III, joined forces with Britain and the Ottoman Empire against Russia. This conflict provided fertile ground for patriotic art, and Pils, perhaps drawing on his father's military background and his own inclinations, became deeply involved in documenting the French army's participation. He traveled to the Crimea as an official artist, tasked with observing and recording the events of the war.

This experience profoundly impacted his choice of subject matter. He produced numerous sketches, watercolors, and ultimately large-scale oil paintings depicting various aspects of the campaign. These were not just idealized battle scenes but often included more mundane, yet telling, moments of military life – soldiers enduring hardship, receiving supplies, or tending to the wounded. His direct observation lent a degree of authenticity and realism to these works that distinguished them from purely imagined historical reconstructions.

One of his most celebrated works from this period is Débarquement des Armées alliées en Crimée (Disembarkation of the Allied Armies in the Crimea), exhibited at the Salon of 1857. This large, complex canvas captured the logistical scale and human drama of the military operation. It was highly praised and earned Pils a medal of honour awarded by Napoleon III himself, cementing his reputation as a leading military painter. Another significant work related to the conflict was the Battle of Alma (1861), depicting the first major Allied victory of the war. This painting, exhibited at the 1861 Salon, also received a medal of honour.

Pils's approach to military painting combined academic compositional structures with a heightened attention to realistic detail, particularly in the rendering of uniforms, equipment, and the varied human responses to war. While still often imbued with a sense of national pride and heroism, his works offered a more grounded perspective than the often more flamboyant battle scenes of earlier painters like Horace Vernet (1789–1863), who had specialized in military subjects under previous regimes. Pils's focus on the common soldier and the realities of campaign life aligned him more closely with the growing taste for Realism, although still framed within an academic context.

Chronicler of the Second Empire

Pils's success as a military painter coincided with the consolidation of the Second French Empire under Napoleon III. The regime actively used art for propaganda purposes, commissioning works that glorified the Emperor, the nation, and especially the army, which was central to Napoleon III's image and foreign policy. Pils became one of the favoured artists of the regime, receiving numerous state commissions.

His painting Soldiers Distributing Bread and Soup to the Poor, exhibited at the 1852 Salon, was an early example of a state commission that blended military themes with social commentary, portraying the army in a benevolent light. While depicting a scene of charity, it also subtly reinforced the order and stability provided by the military under the new imperial regime. The work's realistic depiction of ordinary people and soldiers resonated with contemporary sensibilities.

Another major state commission was La Réception des chefs arabes par l'Empereur et l'Impératrice à Alger, le 18 septembre 1860 (The Reception of the Arab Chiefs by the Emperor and Empress in Algiers, 18 September 1860). Completed later in the decade and submitted to the Exposition Universelle of 1867, this large canvas depicted a key moment in Napoleon III's efforts to consolidate French power in Algeria. Such works served diplomatic and political functions, showcasing the reach and grandeur of the French Empire. Pils's ability to handle large crowds, detailed costumes, and specific historical moments made him well-suited for these official tasks.

During this period, Pils operated within an artistic environment where academic painters received significant state support. While portraitists like Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805–1873) captured the imperial family and aristocracy, and artists like Thomas Couture (1815–1879) created grand allegorical machines, Pils carved out a niche as the preeminent painter of contemporary French military life and history under the Second Empire. His detailed, realistic style, combined with patriotic themes, perfectly suited the needs of the regime.

Major Decorative Projects: The Paris Opéra

Beyond easel painting, Pils also undertook significant decorative commissions. His most famous contribution in this field is the ceiling painting for the Grand Staircase (Grand Escalier) of the Palais Garnier, the new Paris Opéra house designed by architect Charles Garnier (1825–1898). The construction of the Opéra was one of the flagship projects of Baron Haussmann's massive renovation of Paris during the Second Empire, intended as a symbol of imperial prestige and cultural sophistication.

Pils was commissioned in the later stages of the Opéra's decoration, completing the work between 1872 and 1874, just before his death and the Opéra's official opening in 1875. The vast ceiling, titled The Gods of Olympus, the Triumph of Harmony, and the Apotheosis of Music, is a complex allegorical composition featuring numerous figures swirling amidst clouds. It depicts Apollo, the Muses, and various mythological figures associated with music and the arts, celebrating the glory of opera and harmony.

This work required Pils to adapt his style to the demands of large-scale ceiling decoration, employing techniques of foreshortening (sotto in sù) and creating a dynamic composition visible from below. The style is typically academic, blending elements of Baroque grandeur with 19th-century sensibilities. It stands alongside other major decorative cycles within the Opéra, such as the paintings by Paul Baudry (1828–1886) in the Grand Foyer. Pils's contribution to this iconic building further solidified his status within the official art world, demonstrating his versatility across different formats and genres.

Academician and Professor

Pils's success as a painter and his alignment with the official art establishment led to significant academic recognition. In 1863, he was appointed Professor of Painting at the École des Beaux-Arts, the very institution where he had trained. This was a position of considerable influence, allowing him to shape the next generation of French artists according to the principles of the academic tradition. Teaching involved overseeing student work, providing critiques, and upholding the standards of drawing, composition, and historical subject matter.

His academic career culminated in 1868 when he was elected a member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, one of the five academies of the Institut de France. He took the seat previously held by his former master, François-Édouard Picot, who had died that year. Membership in the Académie represented the highest official honour for an artist in France, confirming his place among the elite of the nation's cultural establishment.

As a professor, Pils taught numerous students who went on to have successful careers, although often in styles that diverged from his own as artistic tastes evolved. Among his notable pupils were:

Adrien Moreau (1843–1906), known for his historical genre scenes.

Julien Dupré (1851–1910), who became a celebrated painter of peasant life, associated with the later Realist and Naturalist movements.

Luc-Olivier Merson (1846–1920), recognized for his distinctive historical and religious paintings, often with mystical or Symbolist overtones.

Édouard Dantan (1848–1897), known for his studio scenes and historical subjects.

László Mednyánszky (1852–1919), a Hungarian-Slovak painter influenced by Barbizon and Impressionism, known for his landscapes and scenes of poverty.

Pils's tenure as professor occurred during a period of intense debate and change in the art world. The academic system he represented faced increasing challenges from avant-garde movements. Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) had already championed Realism, focusing on unidealized depictions of contemporary life. By the 1860s and 1870s, the artists who would become known as Impressionists – including Claude Monet (1840–1926), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) – were developing new ways of capturing light and modern experience, often in direct opposition to Salon conventions. Pils remained firmly rooted in the academic tradition throughout these changes.

Later Works and the Franco-Prussian War

Pils continued to paint historical and military subjects in his later years. The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), which led to the downfall of Napoleon III and the Second Empire, provided new, albeit tragic, subject matter. One of his notable later works, though conceived earlier, gained resonance in this period: Rouget de Lisle Singing La Marseillaise (completed 1849, but highly relevant post-1870). This painting depicts the composer presenting the future French national anthem during the revolutionary fervor of 1792. The patriotic theme resonated strongly during and after the Franco-Prussian War, a time of national crisis and the establishment of the Third Republic. The painting is now housed in the Musée historique de Strasbourg.

His health reportedly declined in his later years, possibly exacerbated by the demands of his work, including the physically taxing execution of the Opéra ceiling. He died in Douarnenez, Brittany, while visiting his student Édouard Dantan, on September 3, 1875, shortly after the completion of his work at the Palais Garnier. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, the final resting place of many prominent French cultural figures.

Artistic Style and Technique

Isidore Pils's artistic style is best characterized as Academic Realism, particularly in his mature military works. His training under Lethière and Picot provided him with a strong foundation in Neoclassical principles of drawing and composition. His time in Italy reinforced his appreciation for classical structure and Renaissance masters. However, his direct experiences, especially in the Crimea, pushed him towards a more realistic rendering of detail, texture, and human experience, particularly within the context of military life.

His compositions, especially in large-scale historical and military canvases, are typically well-organized, often featuring numerous figures arranged clearly to convey a narrative or depict a specific event. While adhering to academic norms of anatomical accuracy and idealized forms where appropriate (especially in religious or allegorical works), his military scenes often exhibit a grittier realism in the depiction of soldiers, their uniforms bearing the marks of campaign, and their faces showing fatigue or determination rather than purely heroic archetypes.

He possessed a strong command of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), using it effectively to model forms and create dramatic emphasis. His color palette could range from the somber tones appropriate for religious scenes or depictions of hardship, to the brighter, more varied colors needed for ceremonial events like the Reception of the Arab Chiefs or the vibrant allegories of the Opéra ceiling.

Compared to contemporaries like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), known for his highly polished finish and ethnographic detail in historical and Orientalist scenes, or William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905), famed for his smooth, idealized mythological and genre paintings, Pils's realism often felt more direct and less overtly sentimental or exoticized, especially when dealing with contemporary French subjects. His work provided a bridge between traditional history painting and the growing demand for depictions of modern life, albeit focused primarily through the lens of the military and the state.

Legacy and Conclusion

Isidore Pils was a highly successful and respected artist during his lifetime, embodying the values and achieving the highest honours of the French academic system. He excelled in the prestigious genres of history painting, both religious and military, and secured major state commissions, including significant decorative work for one of Paris's most iconic buildings. His role as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts ensured his influence on a subsequent generation of artists.

His fame rested largely on his military paintings, which captured key moments of the Second Empire and offered detailed, realistic portrayals of French army life. These works resonated with the patriotic sentiments of the era and provided a visual record of France's military endeavors. His shift from primarily religious to military themes reflects broader changes in patronage and national interest during the mid-19th century.

However, like many successful academic artists of his time, Pils's reputation declined significantly after his death with the rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements, which rejected the very principles his art represented. For much of the 20th century, his work was often dismissed as mere official propaganda or academic convention.

In recent decades, however, there has been a renewed scholarly interest in 19th-century academic art, leading to a more nuanced appreciation of figures like Pils. Art historians now recognize the technical skill, compositional complexity, and historical significance of his work. He is seen not just as an academician, but as a specific type of Realist painter operating within the establishment, a chronicler of the military and political life of the Second Empire, and an artist who successfully navigated the complex demands of state patronage, Salon exhibitions, and major public commissions. His paintings, particularly those depicting the Crimean War and the daily life of soldiers, offer valuable insights into the visual culture and social history of 19th-century France. Isidore Pils remains an important figure for understanding the mainstream artistic production of his era, standing as a testament to the enduring power and adaptability of the academic tradition in the face of burgeoning modernity.