Introduction: A Painter of His Time

Léon François Comerre (1850-1916) stands as a significant figure within the French Academic art tradition of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born during a period of artistic transition and societal change, Comerre navigated the established pathways to success, achieving recognition through prestigious institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts and the Paris Salon. He became particularly renowned for his polished, often sensual depictions of female beauty and his engagement with the popular themes of Orientalism. While the avant-garde movements that would define Modernism were emerging during his lifetime, Comerre remained largely dedicated to the principles of Academic painting, mastering its techniques and contributing works that captivated audiences in France and abroad. His career exemplifies the aspirations, training, and aesthetic preferences valued by the official art establishment of the era.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Lille

Léon François Comerre was born on October 10, 1850, in Trélon, a town in the Nord department of northern France. His family relocated to the nearby industrial and cultural center of Lille in 1853. It was in Lille that the young Comerre first displayed a pronounced aptitude for art. The city possessed a respectable artistic environment, fostered in part by the presence of the École des Beaux-Arts de Lille (Lille Academy of Fine Arts), an institution dedicated to nurturing local talent according to established academic principles.

Recognizing his potential, Comerre enrolled at the Lille Academy. He proved to be a dedicated and gifted student, immersing himself in the rigorous training typical of such institutions. This education would have emphasized drawing from plaster casts and live models, the study of anatomy, perspective, and the copying of Old Masters. His progress was notable, culminating in 1867 when, at the age of seventeen, he was awarded a gold medal by the Academy, a significant early validation of his artistic promise. This success marked the end of his initial training phase and set the stage for his move to the epicenter of the French art world: Paris.

Formative Education under Alphonse Colas

During his time at the Lille Academy, Comerre studied under Alphonse Colas (1818-1887). Colas was a respected painter in the region, himself a product of the Academic system, having studied under François Souchon, a pupil of the great Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David. Colas specialized in historical and religious paintings, as well as portraits, and served as a professor and later director of the Lille Academy.

Under Colas's tutelage, Comerre would have honed the foundational skills essential for an Academic painter: precise draughtsmanship, balanced composition, and the traditional application of paint. Colas's emphasis on historical and religious subjects likely provided Comerre with early exposure to the grand genres favored by the official Salon. The gold medal Comerre received in 1867 was a testament not only to his own talent but also to the quality of instruction he received from mentors like Colas, preparing him for the more demanding environment of the Parisian art scene.

Parisian Studies and the École des Beaux-Arts

Armed with his early success and supported by a grant from the Nord department, Comerre moved to Paris to continue his artistic education at the prestigious École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Admission to the École was highly competitive, representing the gateway to official recognition and career advancement within the French art world. The institution was the bastion of Academic tradition, upholding standards derived from classical antiquity and the High Renaissance.

In Paris, Comerre entered the atelier of Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), one of the most celebrated and influential Academic painters of the Second Empire and early Third Republic. Cabanel, himself a winner of the Prix de Rome in 1845, was renowned for his historical, classical, and religious subjects, as well as his elegant, often idealized portraits of high society. His most famous work, The Birth of Venus (1863), purchased by Napoleon III, epitomized the smooth finish, idealized forms, and subtly erotic themes favored by the official taste of the time, standing in stark contrast to the burgeoning Impressionist movement, famously exemplified by Édouard Manet's Olympia shown the same year.

The Influence of Cabanel's Atelier

Studying under Cabanel placed Comerre at the heart of the Academic establishment. Cabanel's studio was highly sought after, and he trained numerous successful artists, including figures like Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Henri Regnault, and Jules Bastien-Lepage (though Bastien-Lepage later developed a distinct Naturalist style). The training in Cabanel's atelier would have been intense, focusing on perfecting drawing skills, mastering complex compositions, and achieving the refined, polished finish characteristic of Cabanel's own work.

Cabanel's influence on Comerre is evident in the younger artist's technical proficiency, his penchant for elegant female figures, and his engagement with historical and mythological themes. While Comerre developed his own distinct style, particularly in his use of color and his embrace of Orientalist subjects, the rigorous training and aesthetic sensibilities absorbed in Cabanel's studio provided the essential foundation for his career. It was within this demanding environment that Comerre prepared for the ultimate academic accolade: the Prix de Rome.

The Prix de Rome: A Crowning Achievement

The Prix de Rome (Rome Prize) was the most prestigious art prize in France, awarded annually by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Winning the prize granted the recipient several years of study at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the magnificent Villa Medici. This period was intended for artists to immerse themselves in the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance, further refining their skills and absorbing the lessons of masters like Raphael and Michelangelo.

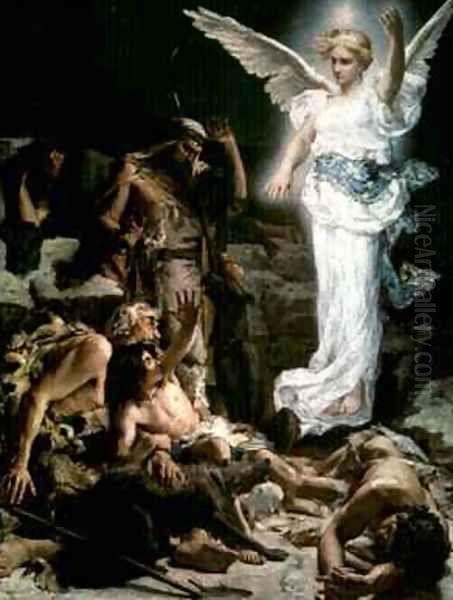

In 1875, Comerre achieved this coveted honor, winning the Prix de Rome in the painting category for his work L'Annonce aux bergers (The Annunciation to the Shepherds, sometimes translated as Angel Announcing the Birth of Christ to the Shepherds). This painting, now housed in the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, demonstrated his mastery of academic conventions: a complex multi-figure composition, skilled rendering of anatomy and drapery, dramatic lighting, and a clear narrative drawn from a traditional religious subject. Winning the Prix de Rome was a major turning point, confirming Comerre's status as one of the most promising young painters of his generation.

Italian Sojourn: Broadening Horizons

Following his Prix de Rome victory, Comerre spent the years 1876 to 1879 at the French Academy in Rome. This period was crucial for his development. Away from the immediate pressures of the Paris Salon, he had the opportunity to travel, study, and absorb the artistic heritage of Italy. The experience exposed him directly to the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters, influencing his understanding of composition, color, and dramatic effect.

While in Rome, artists were expected to send back works (known as envois de Rome) to Paris as proof of their studies. This experience often broadened artists' perspectives, sometimes leading them to explore new subjects or refine their techniques. For Comerre, the Italian sojourn likely reinforced his commitment to figure painting and narrative subjects, while potentially enriching his palette and compositional strategies. It also provided a period of relative freedom before launching his professional career in earnest upon his return to Paris.

Artistic Style: Academicism and Sensuality

Comerre's style is firmly rooted in the Academic tradition taught at the École des Beaux-Arts. This approach emphasized strong drawing skills (dessin), carefully planned compositions, historical or mythological subject matter, and a highly polished finish that minimized visible brushstrokes. The goal was to create idealized, often didactic or narrative works that adhered to established conventions of beauty and propriety. Key figures embodying this tradition earlier in the century included Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis on line and classical form remained influential.

However, Comerre infused the Academic framework with his own sensibilities. He became particularly known for his vibrant, sometimes almost startlingly bright, color palette, which deviated from the more subdued tones often favored by stricter Academics. His brushwork, while generally controlled, could be lighter and more suggestive than that of artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, another highly successful contemporary Academic known for his porcelain-smooth finishes. Most distinctively, Comerre often imbued his subjects, particularly his female figures, with a palpable sensuality, sometimes described by critics as bordering on the erotic or frivolous.

The Allure of Orientalism

A defining characteristic of Comerre's oeuvre is his engagement with Orientalism. This artistic and cultural movement, which swept across Europe in the 19th century, reflected a fascination with the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Fueled by colonial expansion, travel accounts, and a romantic desire for the exotic, Orientalism manifested in paintings depicting bustling souks, opulent harems, dramatic desert landscapes, and captivating local figures. Eugène Delacroix was a key early figure, inspired by his trip to Morocco, while Jean-Léon Gérôme became one of its most meticulous and popular Academic practitioners.

Comerre embraced Orientalist themes enthusiastically, often using them as a vehicle for his preferred subjects: beautiful women in exotic settings. His Orientalist works feature odalisques, dancers, and scenes suggesting Middle Eastern or North African life. These paintings allowed him to explore rich textures (silks, jewels, carpets), dramatic lighting, and compositions filled with decorative details. While visually appealing and popular with collectors, such works also participated in the common tropes of Orientalism, sometimes presenting stereotyped or romanticized visions of Eastern cultures.

Major Themes and Subjects

Comerre's artistic output revolved around several recurring themes:

Portraits of Women: Perhaps his most characteristic subject, Comerre excelled at depicting beautiful women. These ranged from formal society portraits to more allegorical or genre figures. He often captured his sitters with an air of elegance and allure, paying close attention to fashion, expression, and the rendering of skin and fabric. Works like The Girl with Camellias showcase his skill in this area.

Orientalist Scenes: As mentioned, this was a major focus. Paintings like Odalisque with a Water Pipe (1887) or An Arab Beauty are prime examples, combining exotic settings, decorative elements, and sensual female figures. These works catered to the public's taste for the exotic and the picturesque.

Historical and Biblical Subjects: Following his Academic training and Prix de Rome success, Comerre continued to produce works based on history, mythology, and the Bible. His L'Annonce aux bergers falls into this category, as do works like Le Déluge (The Flood) and Judith Beheading Holofernes. These allowed him to tackle complex narratives and demonstrate his mastery of large-scale figure composition.

Allegorical Figures: Like many Academic painters, Comerre occasionally painted allegorical subjects, personifying abstract concepts through often idealized human figures.

Key Works Analyzed

L'Annonce aux bergers (The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1875): This Prix de Rome-winning painting is a cornerstone of Comerre's early career. It depicts the biblical scene where angels announce the birth of Christ to shepherds tending their flocks. The composition is dynamic, featuring dramatically posed figures, swirling drapery, and a strong contrast between the celestial light of the angels and the earthly realm of the shepherds. The work showcases Comerre's technical command, learned under Cabanel, and his ability to handle a complex, multi-figure narrative in the grand Academic style.

Odalisque with a Water Pipe (1887): This painting is representative of Comerre's mature Orientalist phase. It depicts a reclining female figure, an odalisque (a chambermaid or attendant in a harem), in an opulent, vaguely Middle Eastern setting, holding a water pipe (hookah). The subject is rendered with smooth precision, emphasizing her languid pose and direct gaze. The surrounding details – rich textiles, inlaid furniture, decorative tiles – create an atmosphere of exotic luxury. The work exemplifies the blend of technical skill, sensual subject matter, and Orientalist tropes that characterized much of Comerre's popular output. It shares thematic ground with similar works by Gérôme or the American Orientalist Frederick Arthur Bridgman.

The Girl with Camellias: This title likely refers to one of Comerre's numerous portraits or genre scenes featuring elegant women. Such works typically highlight his skill in rendering textures – the softness of skin, the sheen of fabric, the delicate petals of flowers – and capturing a mood of refined beauty or quiet contemplation. These paintings appealed to bourgeois tastes for decorative and pleasing imagery.

The Paris Salon and International Exhibitions

The Paris Salon, the official exhibition organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. Comerre made his Salon debut in 1871 and exhibited there regularly throughout his career. Success at the Salon – positive reviews, awards, state purchases – was crucial for establishing an artist's reputation. Comerre achieved considerable success within this system, winning medals and attracting buyers.

Beyond Paris, Comerre's work gained international exposure. He exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, demonstrating his appeal to British audiences who also had a strong taste for Academic and narrative painting. His participation in the 1885 Antwerp World's Fair, where he won an award, further cemented his international standing. His paintings were also shown and collected in the United States and Australia, indicating the widespread appeal of his polished style and accessible subject matter during his lifetime. This international success placed him among the commercially viable Academic artists of his day.

Comerre in Context: The Late 19th-Century Art World

Comerre's career unfolded during a period of intense artistic debate and transformation. While he operated successfully within the Academic system, this system was increasingly challenged by avant-garde movements. Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, rejected the smooth finish, historical subjects, and studio-bound practices of Academicism in favor of capturing fleeting moments of modern life with visible brushwork and an emphasis on light and color.

Later, Post-Impressionism saw artists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin push artistic boundaries even further, exploring structure, emotion, and symbolism in ways that diverged radically from Academic norms. Comerre and his Academic colleagues, such as Bouguereau, Gérôme, and Cabanel, represented the established order, often viewing these new movements with skepticism or hostility. Gérôme, for instance, was famously opposed to the Impressionists. Comerre's adherence to Academic principles ensured his contemporary success but positioned him on the conservative side of the artistic developments that would ultimately lead to Modernism.

Personal Life and Artistic Connections

In 1884, Comerre married Jacqueline Paton, who became known as Jacqueline Comerre-Paton (1859-1955). She was also a painter, specializing in portraits and genre scenes, and exhibited regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français. Their marriage created an artistic household, and Jacqueline often depicted domestic scenes and portraits of family members. This shared artistic life suggests a supportive environment for Comerre's continued work.

An interesting familial connection links Comerre to the future of art. His nephew was Albert Gleizes (1881-1953), who would become a major theorist and painter of the Cubist movement, alongside artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. This connection highlights the dramatic shift in artistic sensibilities occurring between Comerre's generation and the next. While Comerre represented the pinnacle of Academic training, his nephew would become a key figure in one of the movements that fundamentally overturned those traditions.

Later Career and Recognition

Comerre continued to paint and exhibit successfully into the early 20th century. He maintained his studio in Le Vésinet, a suburb west of Paris popular with artists and writers. His reputation as a skilled portraitist and painter of elegant, often Orientalist, subjects remained solid. He received official recognition for his contributions to French art, being made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour in 1903, a prestigious state award.

His work continued to find favor with collectors who appreciated his technical skill and appealing subject matter, even as the critical tide increasingly turned towards Modernist aesthetics. He remained a respected figure within the established art institutions until his death. Léon François Comerre passed away in Paris on February 20, 1916, during the midst of the First World War.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

For much of the 20th century, following the triumph of Modernism, the reputation of Academic painters like Comerre suffered a significant decline. Their work was often dismissed by critics and art historians as overly sentimental, technically proficient but lacking in originality, or simply out of step with the progressive trajectory of art history. The emphasis shifted towards the avant-garde innovators who had challenged the very foundations upon which Comerre built his career.

However, in recent decades, there has been a scholarly and curatorial reassessment of 19th-century Academic art. Museums and art historians have begun to re-examine figures like Comerre, Bouguereau, Gérôme, and Cabanel, appreciating their technical mastery, understanding their historical context, and acknowledging their immense popularity during their own time. Comerre's work is now studied for its representation of Academic ideals, its engagement with Orientalism, and its reflection of the tastes and cultural preoccupations of Belle Époque France.

While perhaps not considered an innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, Léon François Comerre holds a secure place as a highly skilled and successful exponent of the French Academic tradition. His paintings, particularly his depictions of female beauty and his colorful Orientalist scenes, continue to attract interest for their technical polish, their decorative appeal, and the window they offer onto the official art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Conclusion: A Master of Academic Charm

Léon François Comerre navigated the French art world of his time with considerable skill and success. From his early training in Lille to his studies under the celebrated Cabanel in Paris, and culminating in the prestigious Prix de Rome, he followed the prescribed path to Academic recognition. His oeuvre, characterized by technical finesse, vibrant color, and a focus on idealized female beauty and exotic Orientalist themes, resonated strongly with contemporary audiences and patrons. While the artistic revolutions of Impressionism and Modernism unfolded around him, Comerre remained a steadfast practitioner of the Academic style, creating works that epitomized the elegance, sensuality, and technical polish valued by the Salon and its public. Today, his paintings offer valuable insights into the mainstream artistic culture of the Belle Époque and stand as testaments to the enduring allure of masterful technique applied to popular themes.