Introduction: An Heir to the Golden Age

Jacob van Strij (1756–1815) stands as a significant figure in Dutch art during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Born in Dordrecht, a city steeped in artistic history, Van Strij dedicated his career primarily to landscape painting, carrying forward the rich traditions of the Dutch Golden Age into a new era. While also venturing into seascapes and historical subjects, it is his luminous and tranquil pastoral scenes, often featuring cattle and bathed in a warm, evocative light, for which he is most celebrated. Deeply influenced by the seventeenth-century masters of his hometown, particularly the renowned Aelbert Cuyp, Van Strij developed a distinctive style characterized by technical proficiency, meticulous detail, and a profound sensitivity to atmosphere and light. His work represents a vital link between the towering achievements of the past and the evolving artistic landscape of his own time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Dordrecht and Antwerp

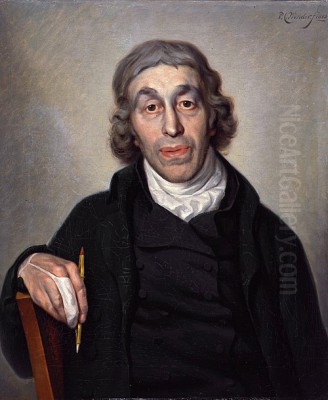

Jacob van Strij was born into an artistic family in Dordrecht, Netherlands, in 1756. His initial artistic training came from his father, Leendert van Strij, who was himself a painter and decorator. This early exposure within the family workshop undoubtedly laid the foundation for Jacob's future career. Dordrecht itself, a city that had nurtured talents like Aelbert Cuyp, Ferdinand Bol, and Nicolaes Maes during the Golden Age, provided a rich historical backdrop for the young artist. Seeking more formal and advanced instruction, Van Strij moved to Antwerp to study at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

In Antwerp, Jacob van Strij had the significant opportunity to study under Andreas Cornelis Lens (1739-1822). Lens was a prominent proponent of Neoclassicism and the director of the Antwerp Academy. Studying with Lens exposed Van Strij to the prevailing academic theories and the emphasis on historical subjects and classical ideals that were gaining traction across Europe. This formal academic training, focusing perhaps more on figure drawing and composition according to classical principles, provided Van Strij with a solid technical grounding, even though his primary passion would ultimately lie in landscape, a genre more deeply rooted in the Dutch tradition than in the Neoclassical mainstream favoured by Lens. This blend of influences – the Dutch landscape tradition absorbed in Dordrecht and the formal Neoclassical training received in Antwerp – would shape his unique artistic path.

The Enduring Influence of the Dutch Masters

While his formal training occurred under a Neoclassical painter, the heart of Jacob van Strij's artistic inspiration lay firmly in the Dutch Golden Age of the seventeenth century. He held a particular reverence for the landscape painters who had flourished over a century before him. Foremost among these influences was Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691), his fellow townsman from Dordrecht. Van Strij deeply admired Cuyp's masterful handling of light – that signature warm, golden glow bathing tranquil river scenes and pastoral landscapes – and his ability to capture the peaceful atmosphere of the Dutch countryside, often populated with placid cattle. Van Strij frequently emulated Cuyp's compositions and luminous effects, leading some later critics to occasionally accuse him of mere imitation, though his best works possess their own distinct character.

Beyond Cuyp, Van Strij also looked closely at the work of other seventeenth-century luminaries. Paulus Potter (1625–1654), famed for his incredibly detailed and lifelike depictions of animals, particularly cattle, clearly informed Van Strij's own careful rendering of livestock. The meticulous attention Potter paid to the anatomy and texture of animals is echoed in Van Strij's work. Additionally, the influence of Adriaen van de Velde (1636–1672), known for his refined and elegant landscapes often featuring graceful figures and animals within idyllic settings, can be discerned. Van Strij absorbed lessons from these masters, studying their techniques for rendering foliage, water, skies, and the interplay of light and shadow. He wasn't alone in looking back; many artists of his era felt the weight and inspiration of the Golden Age masters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema.

Developing a Personal Style: Beyond Imitation

Although Jacob van Strij openly drew inspiration from his seventeenth-century predecessors, particularly Aelbert Cuyp, it would be inaccurate to dismiss him as a mere copyist. While he adopted compositional structures, motifs like cattle near water, and the signature warm lighting associated with Cuyp, Van Strij synthesized these elements into a style that was recognizably his own and suited to the tastes of his time. His technique, honed through academic training, was often smoother and perhaps slightly more formalized than that of some Golden Age painters. His colours could be bright, and his finish meticulous, reflecting the refined sensibilities of the late eighteenth century.

Van Strij demonstrated considerable skill in harmonizing the various elements within his compositions. He adeptly integrated figures and animals into the landscape, ensuring they felt like natural inhabitants of the scene rather than mere additions. His understanding of perspective and atmospheric effects allowed him to create convincing illusions of depth and space. The light in his paintings, while often golden and Cuyp-like, could also possess a clarity and crispness characteristic of his own era. He managed to evoke a sense of tranquility and idealized rural life that appealed to patrons seeking respite from an increasingly complex world. His ability to blend the revered tradition of Dutch landscape with his own technical finesse and contemporary aesthetic marks his unique contribution.

The Van Strij Workshop: A Family Affair

Artistic practice in the Van Strij family was very much a collaborative enterprise. Jacob worked closely with his brother, Abraham van Strij (1753–1826), who was also a painter. Abraham specialized more in genre scenes, portraits, and particularly interior views, often depicting domestic settings with figures, reminiscent of masters like Pieter de Hooch. Together, Jacob and Abraham took over their father Leendert's business, which likely involved decorative painting alongside easel works. In the earlier part of their careers, they collaborated on larger-scale projects, such as decorative wall paintings or panels (known as 'kamerbehangsels') for the homes of wealthy patrons in Dordrecht and beyond.

This type of decorative work was a common practice for artists maintaining a workshop business. It required versatility and the ability to work on a larger scale than typical easel paintings. However, evidence suggests that around the turn of the century, by about 1800, the brothers shifted their focus away from these large decorative commissions. They increasingly concentrated on producing smaller, more detailed 'cabinet paintings' – easel paintings intended for private collection and display in domestic interiors. This shift likely reflected changing tastes among patrons and perhaps allowed each brother to focus more intently on his preferred specializations – Jacob on landscapes and Abraham on interiors and genre scenes, though Jacob certainly included figures and narrative elements in his landscapes. Their partnership highlights the blend of artistry and business acumen required to sustain an artistic career.

Signature Style: Luminous Landscapes and Pastoral Calm

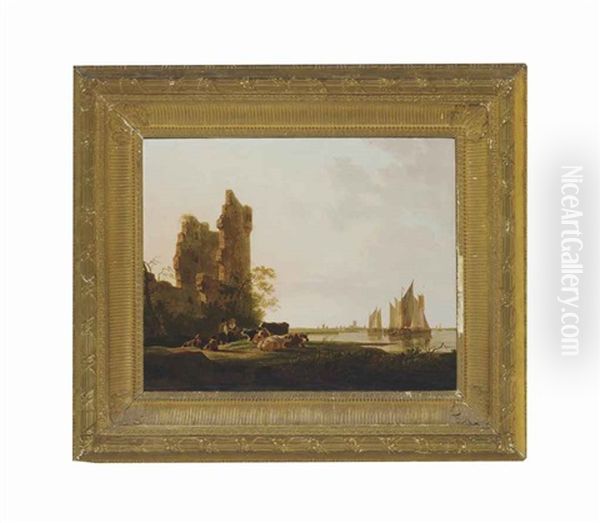

Jacob van Strij's most characteristic works are his pastoral landscapes, which capture an idealized vision of the Dutch countryside. His canvases typically feature rolling meadows, often bordered by water – a river, a canal, or a lake – under expansive skies. Trees, rendered with careful attention to foliage, frame the compositions or stand as focal points within the scene. Distant villages or church spires sometimes appear on the horizon, anchoring the landscape in a specific, albeit often generalized, Dutch locality. The dominant mood is one of peace and serenity, an escape into a harmonious natural world.

Central to these scenes are the animals, particularly cattle. Cows, sheep, and sometimes horses are depicted resting, grazing, or being tended by herdsmen or milkmaids. Van Strij rendered these animals with anatomical accuracy and a sensitivity to their placid nature, following the tradition of Paulus Potter but integrating them seamlessly into the broader landscape composition à la Cuyp. The figures in his paintings – travelers resting, peasants working, milkmaids – are usually small in scale relative to the landscape, emphasizing the dominance of nature. They add narrative interest and a human element but rarely disrupt the overall tranquility.

Perhaps the most defining feature of Van Strij's style is his handling of light and atmosphere. He excelled at depicting the warm, hazy light of late afternoon or early morning, casting long shadows and suffusing the scene with a golden radiance reminiscent of Aelbert Cuyp. This mastery of light creates depth, models form, and, most importantly, establishes the idyllic, peaceful mood that is the hallmark of his best work. His skies are often dynamic, with carefully observed cloud formations contributing to the overall atmospheric effect. The combination of detailed rendering, balanced composition, and evocative lighting defines his enduring appeal.

Key Themes: Celebrating Rural Life and the Dutch Landscape

The recurring themes in Jacob van Strij's work reflect both his personal inclinations and the broader cultural context of his time. The celebration of rural life is paramount. His paintings present an idealized view of the countryside as a place of simple virtues, harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, and peaceful labor. Scenes of milking, herding, and resting travelers evoke a sense of timeless stability and connection to the land. This focus on pastoral themes resonated with an audience that, living through a period of social and political change, may have yearned for such images of tranquility and order.

The Dutch landscape itself is a primary subject. Van Strij's works are rooted in the specific geography of the Netherlands, particularly the riverine areas around his native Dordrecht. While often idealized, his landscapes capture the characteristic features of the region: flat pastures, abundant waterways, distinctive cloud-filled skies, and the interplay of light on water and land. By focusing on these elements, Van Strij continued the long tradition in Dutch art of celebrating the national landscape, which had been a source of pride and identity since the Golden Age. His paintings reinforced a connection to place and heritage.

The prominent inclusion of cattle is also significant. Beyond being picturesque elements, cattle were historically vital to the Dutch economy and symbolized prosperity and the nation's agricultural wealth. Artists like Potter and Cuyp had elevated animal painting to a high art form, and Van Strij proudly continued this tradition, showcasing his skill in rendering these important symbols of Dutch rural life. His work, therefore, operates on multiple levels: as aesthetically pleasing depictions of nature, as idealized representations of rural virtue, and as celebrations of the Dutch landscape and its traditions.

Analysis of Representative Works

Several paintings exemplify Jacob van Strij's style and thematic concerns. Works frequently titled "Milking Time" or similar variations capture a quintessential pastoral moment. These compositions typically feature one or more milkmaids attending to cows in a sun-drenched meadow, often near a body of water. The figures are usually depicted with quiet concentration, integrated naturally into the peaceful setting. The cattle are rendered with care, their forms solid and convincing under the warm light. Such scenes perfectly encapsulate the idealized rural labor and harmonious atmosphere Van Strij sought to convey, directly referencing the tradition of Cuyp.

"Summer landscape with cattle and sheep," exhibited in Dordrecht in 2000, likely showcases similar characteristics. The title suggests a broad vista under a summer sky, populated by the artist's favoured livestock. We can anticipate a composition bathed in warm light, emphasizing the fecundity and tranquility of the season. The interplay between the animals, the landscape elements (meadows, trees, water), and the atmospheric conditions would be central to the painting's effect, demonstrating Van Strij's skill in creating a cohesive and evocative scene.

Paintings like "A River Landscape with Sheep and Cattle," held by institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, often feature expansive views along a waterway. These works allow Van Strij to explore the effects of light on water and depict the flat, open character of the Dutch landscape. The inclusion of boats or distant towns might add further points of interest. The arrangement of the animals along the riverbank, often in relaxed groupings, contributes to the overall sense of peace. These river landscapes are perhaps his most direct homage to Aelbert Cuyp, echoing the latter's famous views of the Maas river near Dordrecht. Works titled "Scène pastorale" or "Landscape with Figures" further attest to his consistent focus on these idyllic rural themes throughout his career.

The Dutch Art Scene: Continuity and Change

Jacob van Strij worked during a period often seen as transitional for Dutch art. The unparalleled brilliance of the seventeenth-century Golden Age, which saw the flourishing of artists like Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals, Jacob van Ruisdael, and many others, had passed. The eighteenth century is sometimes characterized as a period of lesser originality, with many artists looking back to emulate the styles of their famous predecessors. While there's some truth to this, it was also a time of consolidation, technical refinement, and adaptation to new tastes. Neoclassicism, emanating from France and Italy, exerted influence, particularly through academies like the one Van Strij attended in Antwerp under Andreas Lens.

In the Netherlands, however, the native traditions of landscape, genre painting, and still life remained strong. Drawing societies and smaller academies, such as the Teekengenootschap Pictura in Dordrecht (of which Van Strij was a member), played crucial roles in artistic education and maintaining professional standards. Patrons, like the Amsterdam collector Jan Danser Nijman who acquired works by Van Strij, continued to appreciate paintings in the established Dutch modes, particularly those that evoked the Golden Age masters. There was a market for well-executed landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits that maintained high levels of craftsmanship.

Van Strij and his brother Abraham navigated this environment successfully. Their ability to work in both decorative and easel formats, and Jacob's skillful adaptation of the popular Cuyp style, met market demands. While perhaps not radically innovative compared to the seventeenth-century giants, Jacob van Strij was considered one of the leading landscape painters of his generation in the Netherlands. He competed and collaborated within a network of competent artists, including contemporaries like the landscape and cattle painter Pieter Gerard van Os (1776-1839), who worked in a somewhat similar vein, portraitists like Johann Friedrich August Tischbein (who worked for periods in the Netherlands), skilled still-life painters continuing the legacy of Jan van Huysum, and history painters like his own teacher Lens or Dutch artists like Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831).

Contemporaries and Connections

Jacob van Strij's primary artistic connection was undoubtedly with his brother and business partner, Abraham van Strij. Their collaboration shaped their careers, particularly in the early years involving decorative projects. While their specializations diverged somewhat later, their shared background and workshop likely fostered ongoing artistic exchange. Beyond his brother, Van Strij's most significant connections were arguably with the artists of the past whose work he so admired – Cuyp, Potter, Adriaen van de Velde. His engagement with their legacy was a defining feature of his artistic identity.

In terms of living contemporaries, direct records of close friendships or rivalries are scarce. However, he operated within the artistic community of Dordrecht, participating in the Guild of Saint Luke and the Pictura society. This implies interaction with other local artists, though specific names beyond his brother are not prominent in standard accounts of his life. His relationship with his teacher, Andreas Lens, represents a connection to the broader European Neoclassical movement, even if Van Strij ultimately pursued a different path.

His work can be situated alongside other Dutch landscape painters active around 1800. Pieter Gerard van Os, mentioned earlier, also specialized in pastoral landscapes with cattle, sometimes adopting a style influenced by seventeenth-century models, though often with a slightly more robust, less idealized feel than Van Strij's work. Dirk Langendijk (1748-1805) was known for his depictions of military scenes and landscapes, often with horses. Willem van Leen (1753-1825), also from Dordrecht, specialized primarily in flower painting but was part of the same local artistic milieu. While detailed records of direct personal interactions like letters or diary entries specifically involving Jacob van Strij and these contemporaries are not widely known, their shared time, place, and engagement with similar artistic traditions place them within the same artistic context.

Later Life, Health, and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Jacob van Strij's health began to decline. He suffered from severe gout, a painful condition affecting the joints, which would have undoubtedly impacted his ability to work, particularly on larger canvases or potentially even plein air sketching, although the latter was not standard practice then as it became later. Despite these health challenges, he continued to paint, focusing perhaps more on the smaller cabinet pictures that had become a staple of his output alongside his brother Abraham.

Jacob van Strij died in his native Dordrecht on February 4, 1815, at the age of 58 or 59. He left behind a substantial body of work that solidified his reputation as a leading Dutch landscape painter of his time. His success lay in his ability to skillfully evoke the spirit of the beloved seventeenth-century masters, particularly Aelbert Cuyp, while employing a refined technique and appealing sensibility suited to late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century tastes. He provided patrons with beautifully crafted visions of pastoral tranquility and celebrated the enduring beauty of the Dutch landscape.

His legacy is preserved through the numerous paintings held in major museum collections across the world. His works can be found in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Dordrecht Museum (which holds a significant collection related to its native artists), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, among others. Exhibitions, such as the "Held in helder licht" show in Dordrecht in 2000, and the continued appearance of his works at auction houses like Sotheby's, attest to the ongoing appreciation for his art. He remains a key figure for understanding Dutch painting in the period bridging the Golden Age and the modern era.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Eras

Jacob van Strij occupies an important position in the narrative of Dutch art history. He was an artist deeply respectful of the towering achievements of the seventeenth-century Golden Age, consciously modelling his work on masters like Aelbert Cuyp and Paulus Potter. Yet, he was not merely an imitator. He filtered these influences through his own refined technique and the aesthetic sensibilities of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, creating landscapes characterized by luminous light, pastoral calm, and meticulous execution. Working alongside his brother Abraham, he successfully navigated the art market of his time, producing both decorative works and highly sought-after cabinet paintings.

His dedication to the Dutch landscape, rendered with a distinctive blend of idealized tranquility and observational detail, ensured his popularity during his lifetime and secured his place in major collections. While living in the long shadow of the Golden Age, Van Strij demonstrated how its traditions could be meaningfully adapted and revitalized for a new generation. He stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of the pastoral landscape and the specific beauty of the Dutch countryside, captured with skill, sensitivity, and a masterful handling of light. His work offers a window onto the artistic values and aspirations of the Netherlands during a period of transition, forming a vital bridge between the nation's celebrated artistic past and its future developments.