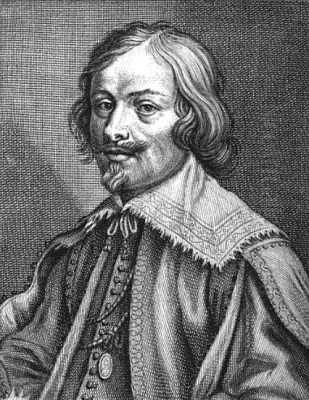

Jacques Callot (1592-1635) stands as a monumental figure in the history of printmaking, a master etcher whose intricate works captured the breadth of human experience during the tumultuous Baroque era. Born in the Duchy of Lorraine, a region frequently caught in the crosscurrents of European conflict, Callot's life and art were deeply intertwined with the social, political, and religious upheavals of his time. His technical innovations revolutionized the medium of etching, while his keen eye and sharp needle documented everything from courtly splendors and theatrical performances to the grim realities of war and the lives of the marginalized. His legacy extends far beyond his native France, influencing generations of artists across Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Jacques Callot was born in Nancy, the capital of the independent Duchy of Lorraine, into a family connected to the ducal court. His father, Jean Callot, was a herald-at-arms, a position of some standing, and his mother was the daughter of a court goldsmith. Despite this artistic connection through his maternal grandfather, Callot's parents initially envisioned a different path for him, perhaps in the clergy or the military, professions deemed more suitable for a young man of his station.

However, the young Jacques displayed an early and undeniable passion for art. Nancy, under Dukes Charles III and Henri II, was a vibrant cultural center, and Callot would have been exposed to the arts from a young age. Traditional accounts, though perhaps embellished, speak of his youthful determination, suggesting he even ran away from home in his early teens, attempting to reach Italy with traveling groups, possibly including Romani people (gypsies), a subject he would later depict with fascination.

Formal training began closer to home. Around the age of fifteen or sixteen, he is thought to have studied drawing under Claude Henriet, a court painter. He also likely received instruction in the decorative arts from Demange Crocro, a goldsmith and engraver, which would have provided foundational skills in working with metal, crucial for his later printmaking career. Yet, the allure of Italy, the epicenter of Renaissance and Baroque art, remained strong. His desire to master the techniques of engraving and etching ultimately led him to leave Lorraine and embark on the journey that would shape his artistic destiny.

The Italian Apprenticeship: Rome and Florence

Around 1608, Callot finally made his way to Italy, the destination for ambitious artists across Europe. His first significant stop was Rome. There, he reportedly entered the workshop of Philippe Thomassin, a French expatriate engraver and print publisher. Working in such an environment would have immersed him in the techniques of copperplate engraving and exposed him to the vast repertoire of classical and contemporary Italian art. Some sources also suggest an association with Antonio Tempesta, another prolific printmaker known for his battle scenes and hunts, whose dynamic compositions may have influenced Callot.

Rome offered a rich artistic tapestry. Callot would have studied the works of Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, as well as contemporary Baroque artists. He absorbed the principles of composition, anatomy, and dramatic expression that were hallmarks of Italian art. His time in Rome was crucial for honing his technical skills, particularly in engraving, the dominant intaglio technique at the time.

By 1611, Callot had moved north to Florence, a city still basking in the artistic legacy of the Renaissance and enjoying the patronage of the powerful Medici family. This move proved pivotal. He entered the service of Grand Duke Cosimo II de' Medici, a significant patron of the arts and sciences. In Florence, Callot began to focus more intensely on etching, a technique offering greater freedom and spontaneity than engraving.

A key figure during his Florentine period was Giulio Parigi, an architect, designer, and printmaker who oversaw court festivities and theatrical productions for the Medici. Callot worked closely with Parigi, etching plates based on Parigi's designs for elaborate events, masques, and stage sets. This collaboration deeply influenced Callot's sense of theatricality, his skill in arranging large crowds within complex perspectives, and his fascination with costume and performance. Works like the series documenting the funeral of the Queen of Spain (1612) and depictions of Florentine festivals, such as La Festa di Impruneta, showcase his developing style during this period.

Technical Innovations in Etching

While in Florence, Callot made significant technical advancements that transformed the art of etching. Before Callot, etchers typically used a soft, wax-based ground to protect the copper plate from the acid bath. This soft ground was easily scratched, limiting the fineness of detail and often leading to accidental marks. Lines tended to be relatively uniform in width.

Callot experimented with different materials and pioneered the use of a hard ground, employing a type of varnish used by lute-makers, likely a mixture of mastic and linseed oil. This hard ground was more resistant to accidental scratches and allowed for much finer, more precise linework. It could withstand multiple immersions in acid, enabling Callot to develop a system of "stopping-out." By covering certain areas with varnish between acid baths, he could achieve a wider range of tonal values, creating lighter lines for distant objects and deeper, darker lines for the foreground, enhancing the sense of depth and atmosphere.

Furthermore, Callot popularized the use of a specialized etching needle called an échoppe. This tool had a slanted, oval tip rather than a simple point. By varying the angle and pressure, Callot could create lines that swelled and tapered, mimicking the dynamic quality of engraved lines but with the greater freedom of etching. This allowed for more expressive and varied mark-making, contributing to the vibrancy and detail of his prints.

These technical innovations were revolutionary. They elevated etching from a sometimes-crude technique to a highly refined medium capable of sophisticated artistic expression. Callot's mastery of hard ground, stopping-out, and the échoppe enabled him to create prints of unprecedented detail, complexity, and tonal richness, particularly remarkable given the often small scale of his works. He became known as a "Master of the Diminutive" for his ability to pack vast amounts of information and lively figures into tiny compositions.

Return to Lorraine and the Shadow of War

The death of Callot's patron, Grand Duke Cosimo II de' Medici, in 1621 marked a turning point. Without his primary source of support in Florence, Callot decided to return to his native Nancy. He arrived back in Lorraine an accomplished artist with an international reputation, having spent over a decade honing his craft in Italy. He received commissions from the ducal court of Lorraine under Henri II and later Charles IV, as well as from religious orders and publishers.

However, the Lorraine he returned to was increasingly overshadowed by the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), a devastating conflict that ravaged central Europe. Though initially trying to maintain neutrality, the Duchy of Lorraine became embroiled in the complex political and military struggles between France, the Holy Roman Empire, and various Protestant and Catholic factions. This period of escalating tension and violence would profoundly impact Callot's life and provide the subject matter for his most famous and harrowing works.

His position as a court artist sometimes placed him in difficult situations. He traveled to the Low Countries and Paris on commissions, including one from the Infanta Isabella in Brussels to commemorate the Spanish Siege of Breda, and another from King Louis XIII of France to depict the Siege of La Rochelle and the Siege of the Île de Ré. These commissions demonstrated his renown but also highlighted the complex political landscape he navigated.

The relative stability of his early years back in Nancy gradually eroded as French influence and military pressure increased. The French invasion of Lorraine in 1633 brought the war directly to his homeland, leading to widespread suffering and devastation. This grim reality became the unavoidable backdrop to his later artistic production.

Masterpiece of Conflict: The Miseries of War

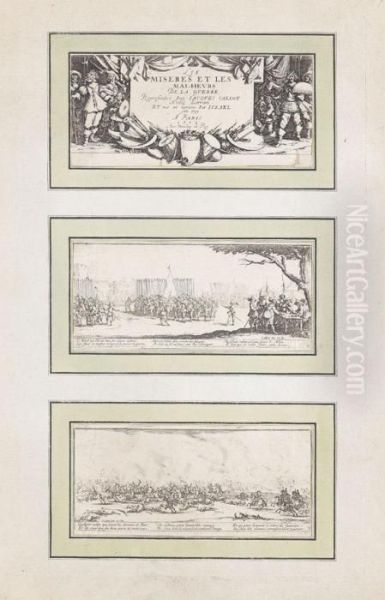

Callot's most enduring legacy is arguably his unflinching depiction of conflict, culminating in the series Les Grandes Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre (The Great Miseries and Misfortunes of War), published in 1633. This set of eighteen etchings provides a brutal and comprehensive chronicle of the impact of the Thirty Years' War, not just on soldiers but profoundly on the civilian population.

Unlike many contemporary depictions that glorified military leaders or focused on strategic maneuvers, Callot presented war stripped of its romance. The series unfolds episodically: the recruitment of soldiers, battle scenes, marauding troops pillaging villages, the infamous plate of 'The Hanging Tree' showing mass execution, scenes of torture and retribution, the burning of homes, the suffering in military hospitals, peasants taking revenge on soldiers, and the final plates showing the distribution of rewards to commanders juxtaposed with the miserable fate of wounded and impoverished veterans.

Each small plate is a marvel of detailed observation and compositional skill. Callot uses his refined etching technique to render chaotic scenes with clarity, populating landscapes with tiny figures engaged in acts of shocking violence or enduring profound suffering. The panoramic views often contrast the beauty of the natural setting with the horrors inflicted by humanity. There is a sense of detached yet compassionate observation, allowing the stark reality of the events to speak for themselves.

While possibly commissioned initially by Louis XIII or Cardinal Richelieu (perhaps related to the French invasion of Lorraine), the series transcends mere propaganda. It serves as a powerful, universal indictment of the barbarity of war and its devastating consequences on society. It established a new benchmark for the artistic representation of conflict, moving away from heroic narratives towards a focus on human suffering. This series profoundly influenced later artists grappling with the theme of war, most notably Francisco Goya in his Disasters of War series nearly two centuries later. Callot had also produced an earlier, smaller set on the same theme, Les Petites Misères de la Guerre, around 1632.

A Diverse Oeuvre: Beyond the Battlefield

While The Miseries of War is perhaps his most famous work, Callot's output was incredibly diverse, encompassing over 1,400 prints throughout his career. His subject matter ranged widely, reflecting the varied experiences of his life in Italy and Lorraine.

Religious themes remained important. He produced numerous prints depicting biblical scenes, lives of saints, and allegorical representations of faith. The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a subject he revisited, allowed him to indulge his fantastical imagination, filling the scene with grotesque demons and bizarre creatures reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch or Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Other works, like The Transfiguration or series on the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, demonstrate a more restrained, devotional quality, showcasing his ability to handle traditional subjects with technical finesse.

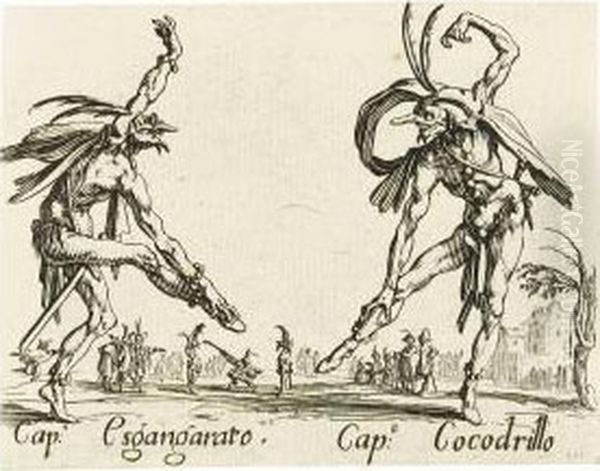

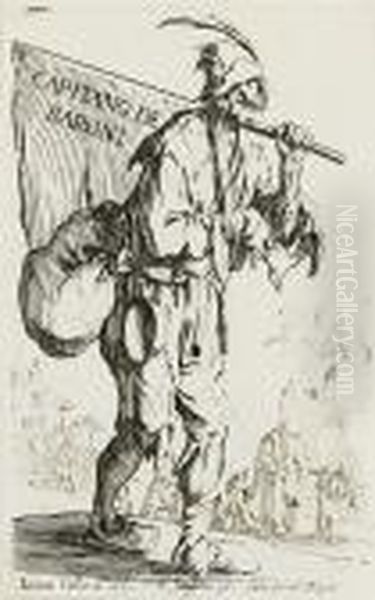

His experience working with Giulio Parigi in Florence fostered a lifelong interest in theatre and performance. He created lively etchings of Commedia dell'arte characters, capturing their exaggerated postures and masks. The Balli di Sfessania (Dances of Sfessania) depicts pairs of acrobatic, often grotesque dancers in energetic, almost violent motion. He also documented courtly entertainments, tournaments, and processions, such as Le Banquet du Roi, preserving the ephemeral spectacles of Baroque court life.

Callot possessed a sharp eye for social observation. His series Les Gueux (The Beggars) portrays various types of beggars, vagrants, and disabled individuals with a mixture of sympathy and caricature, reflecting contemporary societal attitudes but also acknowledging the humanity of society's outcasts. Similarly, his depictions of Romani people (Gypsies), such as Les Bohémiens, show groups traveling, setting up camp, and fortune-telling, capturing their distinct way of life with ethnographic curiosity, though sometimes tinged with stereotype. His Capricci di Varie Figure, produced in Florence, is a series of small, imaginative prints featuring diverse character types, soldiers, and scenes, showcasing his inventive flair and technical skill early in his career.

The Art of Observation: Realism and Caricature

Callot's style is characterized by a unique blend of meticulous realism and expressive distortion. His commitment to observation is evident in the incredible detail packed into even his smallest prints. He rendered architecture, landscapes, costumes, and human anatomy with remarkable accuracy. His ability to manage complex compositions involving hundreds of figures, maintaining clarity and suggesting deep space, was unparalleled.

However, he was not merely a dispassionate recorder. His figures, though often tiny, are imbued with life and energy. He frequently employed exaggeration and caricature, particularly when depicting peasants, beggars, soldiers, or theatrical characters. This tendency connects him to the Mannerist tradition, with its emphasis on elongated forms, artificial poses, and heightened emotional states, which he would have absorbed in Florence. Artists like Federico Barocci or even late Michelangelo might be seen as distant precursors in terms of expressive figuration.

His use of caricature often served satirical or humorous ends. In works like the Balli di Sfessania or some of the beggar prints, the exaggeration borders on the grotesque, highlighting the absurdity or harshness of the human condition. Yet, even in his most critical depictions, such as The Miseries of War, there is an underlying humanism. He observes folly and cruelty but rarely seems to condemn wholesale, instead presenting a complex, often tragic, view of humanity. This combination of sharp observation, technical brilliance, and expressive exaggeration defines his unique artistic voice. Comparisons can be drawn to the satirical intent found later in the works of William Hogarth, though Callot's style remained rooted in the Baroque linear tradition.

Collaborations and Connections

Throughout his career, Callot interacted with various artists, patrons, and publishers who shaped his path. His early work under Philippe Thomassin and possibly Antonio Tempesta in Rome provided crucial training and exposure to the print market. His collaboration with Giulio Parigi in Florence was particularly formative, immersing him in the world of Medici court spectacle and influencing his compositional strategies.

Back in Lorraine, he maintained connections with the ducal court and received commissions from local nobility and religious institutions. His travels also brought him into contact with artistic developments elsewhere. His visit to the Low Countries put him in touch with the vibrant art scene there, potentially encountering the works of Flemish masters like Peter Paul Rubens, who is known to have collected Callot's prints.

While direct documented friendships with major painters are scarce, his work existed within a broader artistic context. His contemporary in Lorraine, the painter Georges de La Tour, shared Callot's interest in realism and dramatic lighting, though their styles were vastly different. De La Tour focused on intimate, candlelit scenes, while Callot excelled in panoramic, populated vistas. Yet, both artists brought a new intensity of observation to French art. There has been speculation about whether Callot studied under the Mannerist painter Jacques Bellange in Nancy before leaving for Italy, but concrete evidence is lacking, and Callot's primary development occurred during his Italian sojourn.

His prints circulated widely, influencing artists who may never have met him personally. His technical innovations and thematic choices became part of the visual language available to subsequent generations of printmakers across Europe.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

Jacques Callot's impact on the history of art, particularly printmaking, is undeniable and far-reaching. His technical innovations fundamentally changed the possibilities of etching, paving the way for later masters of the medium. His influence was felt almost immediately and continued for centuries.

Rembrandt van Rijn, arguably the greatest etcher of the Dutch Golden Age, was a known admirer and collector of Callot's prints. While Rembrandt developed his own deeply personal style, Callot's influence can be discerned in Rembrandt's sophisticated use of etching techniques, his handling of crowd scenes, and his interest in depicting beggars and everyday life, albeit with greater psychological depth.

As mentioned, Francisco Goya's powerful Disasters of War series owes a clear debt to Callot's Miseries of War. Goya adopted Callot's episodic structure and unflinching portrayal of brutality, adapting it to the context of the Napoleonic Wars in Spain and infusing it with his own dark, expressive vision.

In England, the satirical tradition, particularly the narrative series of William Hogarth, echoes Callot's use of print sequences to comment on society, though Hogarth's focus was more on contemporary urban morals. Later caricaturists like George Cruikshank also operated in a lineage traceable back to Callot's blend of observation and exaggeration.

In landscape and cityscape depiction, artists like the Italian Canaletto and the French painter Carle Vignola drew inspiration from Callot's detailed rendering of architecture and his ability to create convincing spatial depth in panoramic views. The Bohemian etcher Wenceslaus Hollar, working primarily in England, clearly absorbed Callot's techniques for detailed topographical and figurative work.

Beyond the visual arts, Callot's imaginative and sometimes grotesque imagery captivated writers. The German Romantic author E.T.A. Hoffmann was fascinated by Callot's prints, even titling a collection of his stories Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (Fantasy Pieces in Callot's Manner), attesting to the evocative power of the artist's vision. Callot established etching as a major independent art form in France and set a standard for technical excellence and thematic breadth that resonated throughout Baroque and subsequent European art.

Later Life and Final Years

Callot spent the last fourteen years of his life primarily in Nancy, working prolifically despite the increasingly troubled times. He continued to receive prestigious commissions, such as the large plates depicting The Siege of Breda (commissioned by the Spanish Infanta) and The Siege of La Rochelle (for the French King Louis XIII), showcasing his skill in rendering complex military events with topographic accuracy and dramatic flair.

A famous anecdote, recounted by his biographer André Félibien, illustrates his loyalty to his homeland. When Louis XIII's forces occupied Nancy in 1633, the King or his minister Cardinal Richelieu allegedly asked Callot to make a print commemorating the French victory and the siege of his own capital city. Callot is said to have refused, declaring he would sooner cut off his thumb than depict the humiliation of his Duke and his city. Whether entirely factual or not, the story reflects his reputed integrity and his connection to Lorraine.

His final years were marked by the ongoing war and its hardships. Despite the turmoil, he continued to create, producing religious works, genre scenes, and the powerful Miseries of War series during this late period. Jacques Callot died in Nancy on March 24, 1635, at the relatively young age of about 43. The exact cause of his death is unknown, but the era was fraught with disease and hardship exacerbated by war.

Conclusion

Jacques Callot was more than just a technically brilliant etcher; he was a profound observer of the human condition in all its complexity. From the glittering courts of Florence to the ravaged landscapes of war-torn Lorraine, his sharp eye and sharper needle captured the essence of the Baroque age – its splendors and miseries, its faith and brutality, its theatricality and harsh realities. His innovations pushed the boundaries of printmaking, creating a new language of fine lines, rich tones, and dynamic compositions. His vast body of work, remarkable for its diversity and detail, provides an unparalleled visual chronicle of his time. Through masterpieces like The Miseries of War, he confronted the horrors of conflict with an honesty that still resonates today. His influence on artists from Rembrandt to Goya cements his status as a pivotal figure, a true master whose miniature worlds continue to fascinate and inform.