Introduction: The Heir to a Great Name

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, often known simply as Domenico, stands as a significant figure in the twilight of the Venetian Republic's artistic glory. Born in Venice on August 30, 1727, and passing away in the same city on March 3, 1804, his life spanned a period of profound artistic and social change. He was not merely a painter but also a gifted etcher and engraver, working primarily within the exuberant Rococo style that characterized much of 18th-century European art. His legacy, however, is complex, forever intertwined with that of his immensely famous father, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (often called Giambattista), the undisputed master of large-scale decorative fresco painting. Domenico, along with his younger brother Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo, was born into an artistic dynasty, destined from a young age to follow in his father's footsteps. Yet, while he absorbed Giambattista's techniques and initial style, Domenico forged his own distinct artistic identity, marked by a growing interest in realism, narrative detail, and the intimate portrayal of everyday life, often infused with a unique sense of humor and satire.

Early Life and Apprenticeship in the Tiepolo Workshop

Domenico's artistic education began almost from birth within the bustling environment of his father's workshop, one of the most successful and sought-after in Europe. Venice, at this time, was still a vibrant center for the arts, though its political and economic power was waning. The demand for decorative schemes for palaces, villas, and churches remained high, providing ample work for skilled artists. Giambattista Tiepolo's workshop was renowned for its efficiency and the dazzling quality of its output, characterized by luminous palettes, airy compositions, and seemingly effortless execution – the embodiment of Rococo grace.

From a very early age, Domenico showed artistic promise. By the tender age of 13, he was already considered his father's principal assistant, a testament to his precocious talent and rapid absorption of the family style. This apprenticeship was not formal schooling in the modern sense but rather hands-on training. He would have learned by grinding pigments, preparing surfaces, copying his father's drawings, executing less critical parts of large compositions, and gradually taking on more responsibility as his skills developed. This immersive experience provided him with an unparalleled technical foundation in drawing, oil painting, and the demanding art of fresco. His brother Lorenzo also trained and worked alongside them, contributing to the family enterprise.

Major Collaborations: Würzburg and Vicenza

Domenico's formative years were dominated by assisting his father on monumental commissions that cemented the Tiepolo name across Europe. The most significant of these early collaborations was the decoration of the Würzburg Residenz in Germany (1751-1753). Summoned by the Prince-Bishop Carl Philipp von Greiffenclau zu Vollraths, Giambattista, accompanied by Domenico and Lorenzo, embarked on decorating the Kaisersaal (Imperial Hall) and the vast ceiling above the Residenz's magnificent staircase, designed by architect Balthasar Neumann.

The scale of the Würzburg project was immense. The staircase ceiling, depicting an Allegory of the Planets and Continents, remains one of the largest frescoes in the world. Domenico played a crucial role in its execution, working closely under his father's direction. While Giambattista would have designed the overall composition and painted key figures, Domenico was responsible for significant portions of the work. This experience exposed him to the demands of court patronage and the challenges of creating cohesive, grand-scale narratives that glorified the patron and filled enormous architectural spaces with light and movement. It also provided him the opportunity to study the works of earlier masters and interact with the German artistic environment, although the Tiepolo style remained distinctly Venetian.

Another vital collaborative project was the decoration of the Villa Valmarana ai Nani, near Vicenza (1757). Here, Giambattista decorated the main residence (Palazzina) with scenes from epic poems like Homer's Iliad, Virgil's Aeneid, Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, and Ariosto's Orlando Furioso. Simultaneously, Domenico took the lead in decorating the guest house (Foresteria). While some rooms continued mythological or classical themes, others featured scenes of country life, carnival figures, and chinoiserie. These Foresteria frescoes are often seen as an early indication of Domenico's burgeoning independence and his growing interest in genre subjects, depicting everyday activities and popular entertainment with a directness and charm that subtly diverged from his father's more heroic style.

Forging an Independent Path: Early Commissions and Stylistic Evolution

While deeply involved in his father's projects, Domenico began undertaking independent commissions relatively early. Around the age of 20, he started producing works for private clients. A significant early independent project was the series of fourteen paintings depicting the Stations of the Cross (Via Crucis) for the Oratory of the Crucifix at the church of San Polo in Venice (1747-1749). This series, completed when he was barely in his twenties, demonstrated his ability to handle a major religious cycle with dramatic intensity and emotional depth. The compositions are powerful, using strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and focusing on the human suffering within the sacred narrative. While the influence of Giambattista is still apparent, there's a tangible weight and pathos that hints at Domenico's own sensibility.

As his career progressed, Domenico's style continued to evolve. While he never fully abandoned the bright palette and fluid brushwork inherited from his father, his work often displayed a greater grounding in reality. He seemed less interested in the soaring, illusionistic heavens that were his father's specialty and more focused on observable human interaction, detailed settings, and narrative clarity. His figures often feel more solid, his compositions less ethereal and more staged. This shift can be seen as aligning with broader trends in Venetian art, where artists like Pietro Longhi were documenting the city's social rituals and daily life in small-scale genre paintings, albeit in a very different, more anecdotal style than Domenico's.

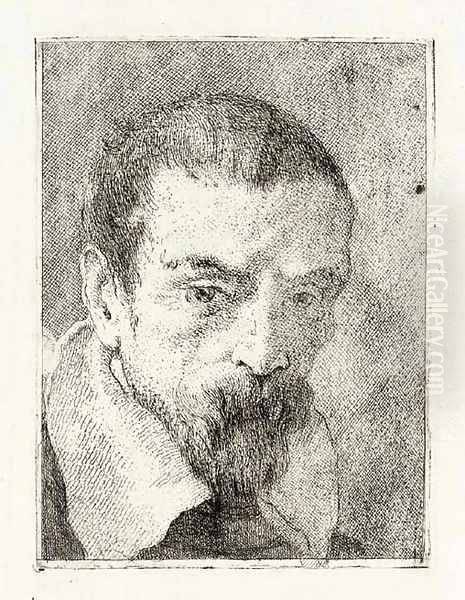

Mastery in Printmaking: Etchings and Drawings

Beyond his work as a painter, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo was a prolific and highly accomplished printmaker, particularly skilled in etching. This medium allowed him a different kind of creative freedom, suited to smaller formats, intricate detail, and personal expression. He produced numerous etchings throughout his career, some reproducing his own or his father's paintings, but many being original compositions.

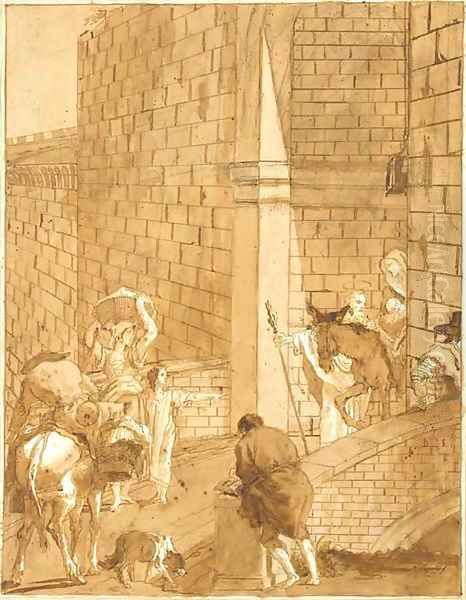

One of his most celebrated series of etchings is the Raccolta di Teste (Collection of Heads), based on his father's studies but interpreted with Domenico's own graphic sensibility. Even more significant is the series Idee Pittoresche sopra la Fuga in Egitto (Picturesque Ideas on the Flight into Egypt), comprising 24 plates plus a title page and dedication, completed around 1753. Dedicated to the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg, this series explores the journey of the Holy Family with remarkable inventiveness and tenderness. Rather than focusing solely on the divine aspect, Domenico depicts intimate, human moments set within richly detailed landscapes – the family resting, crossing a river, interacting with angels and ordinary people. The series showcases his mastery of light, texture, and atmospheric effects within the etching medium.

He also produced sets of prints known as Capricci and Scherzi di Fantasia, echoing similar series by his father but possessing their own distinct character. These prints often feature enigmatic scenes with magicians, satyrs, soldiers, and melancholic figures in crumbling architectural settings, demonstrating a fascination with the exotic, the arcane, and the passage of time, themes also explored by contemporaries like Giovanni Battista Piranesi in his famous etchings of Roman ruins, though Piranesi's focus was more archaeological and monumental.

The World of Pulcinella: A Late Masterpiece in Drawing

Perhaps Domenico Tiepolo's most personal and unique creation is the extensive series of drawings known as the Divertimento per li Regazzi (Entertainment for Children), centered around the character of Pulcinella (or Punchinello). Pulcinella was a stock character from the Italian Commedia dell'arte, a hook-nosed, humpbacked trickster figure known for his anarchic energy, gluttony, and slapstick humor. Domenico created 104 pen and brown wash drawings, plus a title page, likely late in his life (mostly in the 1790s), seemingly for his own pleasure rather than for a specific commission.

This series follows Pulcinella through various stages of life – his parentage (hatched from a turkey egg), childhood, adventures, trades, marriage, fatherhood, encounters with animals, other Commedia figures, and ultimately his death, burial, and even posthumous appearances. The drawings are executed with astonishing freedom and vibrancy. They blend humor, satire, social commentary, and moments of unexpected melancholy and violence. Pulcinella becomes an everyman figure, his exaggerated antics reflecting the follies and struggles of human existence. The series offers a fascinating glimpse into Venetian popular culture and Domenico's own complex worldview, moving far beyond the aristocratic elegance often associated with the Rococo. It stands as a singular achievement in graphic art, admired for its narrative richness, psychological depth, and sheer imaginative power.

Themes and Artistic Characteristics

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo's subject matter was diverse. He continued to paint religious scenes throughout his career, fulfilling commissions for churches in Venice and the Veneto region. Notable examples include works for San Francesco di Paola and San Lio in Venice. He also tackled mythological and historical themes, often required by patrons seeking grand decorations in the established Tiepolo manner. His large painting, The Procession of the Trojan Horse into Troy (c. 1760), now in the National Gallery, London, exemplifies his ability to handle complex historical narratives with dramatic flair, populating the scene with numerous figures and rich detail, though perhaps with less of the effortless buoyancy found in his father's historical works.

However, Domenico truly excelled in depicting scenes inspired by contemporary life and popular entertainment. His paintings of Venetian carnivals, elegant figures promenading, and theatrical performances capture the spirit of the age. The Minuet (c. 1756), possibly inspired by the plays of Carlo Goldoni, the great Venetian playwright who reformed Commedia dell'arte, depicts dancers and masked onlookers in a salon, showcasing his keen observation of social manners and costumes. His interest in genre extended to rural scenes and depictions of everyday people, often treated with sympathy and realism, as seen in the frescoes of the Villa Valmarana Foresteria.

A recurring characteristic noted in the provided text is his use of satire and humor, sometimes bordering on the grotesque. This is most evident in the Pulcinella drawings but also surfaces in other works. He could subtly undermine the grandeur of a mythological scene or inject a note of irony into a religious depiction, such as the mentioned St. Ambrose Instructing the Young St. Augustine using unusual props. This satirical edge distinguishes him from the more consistently idealized world of his father and aligns him with other critical observers of the era, perhaps even foreshadowing the sharper social commentary found in the works of the Spanish master Francisco Goya, who was a contemporary.

Artistic Circle and Influences

Domenico's primary influence was, undeniably, his father, Giambattista Tiepolo. He absorbed his father's techniques, compositional strategies, and approach to color and light. His brother, Lorenzo Tiepolo, was also a collaborator and painter, though his independent output is less extensive and often harder to distinguish from Domenico's during their collaborative periods.

Within the broader Venetian context, Domenico was aware of and responded to the work of other leading artists. The source text mentions Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Sebastiano Ricci as figures within his artistic milieu. Piazzetta was known for his more tenebrous style and his poignant genre scenes, which may have resonated with Domenico's own interest in realism and emotional depth. Ricci was a key figure in the development of the Venetian Rococo before Giambattista Tiepolo, known for his light-filled, dynamic compositions.

Other important Venetian contemporaries included Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, masters of the veduta or view painting, whose detailed depictions of the city reflected a similar interest in observing the contemporary world, albeit with a focus on topography and atmosphere. Rosalba Carriera, the celebrated pastel portraitist, contributed significantly to the Rococo sensibility with her delicate and psychologically insightful portraits. Pietro Longhi, as mentioned, specialized in intimate scenes of Venetian aristocratic life. While Domenico's grander scale and different focus set him apart, he operated within this rich artistic ecosystem. His international experience, particularly in Würzburg and later Spain, also exposed him to different artistic currents, though his style remained fundamentally Venetian.

The Spanish Sojourn and Later Years

In 1762, Domenico accompanied his father and brother Lorenzo to Madrid, summoned by King Charles III of Spain to decorate ceilings in the new Royal Palace. This was another major undertaking, where Domenico again assisted his father on vast frescoes, such as the Apotheosis of Spain in the Throne Room. They remained in Spain for several years, navigating the politics of the Spanish court and interacting with other artists present there, including the Neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs, whose more austere style represented the emerging artistic trend that would eventually supplant the Rococo.

Giambattista Tiepolo died suddenly in Madrid in 1770. After his father's death, Domenico, rather than remaining in Spain where Neoclassicism was gaining favor, chose to return to Venice. He settled back into the city of his birth, inheriting his father's villa in Zianigo, near Mirano on the mainland. He continued to work actively as a painter and etcher. In 1780, he was elected President of the Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Venice, a mark of the high esteem in which he was held by his peers.

During his later years, he undertook further commissions, including frescoes for the Palazzo Contarini in Venice and, notably, the ceiling decoration for the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa in 1785, depicting the Allegory of Liguria and the Glories of the Giustiniani Family. He also decorated rooms in his own villa at Zianigo with frescoes, including many scenes featuring Pulcinella, transferring themes from his private drawings onto the walls of his home. These Zianigo frescoes, detached and now largely preserved in the Ca' Rezzonico museum in Venice, offer invaluable insight into his personal artistic preoccupations during his final decades. He continued to work until shortly before his death in Venice on March 3, 1804, at the age of 76.

Legacy and Evaluation

For a long time, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo's reputation was overshadowed by that of his father. Giambattista's dazzling frescoes were seen as the pinnacle of Venetian decorative painting, and Domenico was often viewed primarily as a talented assistant and follower. The rise of Neoclassicism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries led to a decline in the appreciation of Rococo art in general, and the Tiepolos' work fell somewhat out of fashion, criticized for its perceived frivolity and lack of moral seriousness compared to the stern virtues promoted by artists like Jacques-Louis David in France.

However, the 20th century saw a significant re-evaluation of Domenico's work, particularly his drawings and prints. Scholars and collectors came to appreciate the unique qualities of his art: his keen powers of observation, his narrative skill, his psychological insights, and his distinctive blend of humor, satire, and melancholy. The Flight into Egypt etchings and, above all, the Pulcinella drawings are now recognized as masterpieces of graphic art, revealing a complex and highly original artistic personality.

While he masterfully employed the Rococo vocabulary learned from his father, especially in large-scale commissions, Domenico infused it with his own interests. His focus on genre, his exploration of popular culture, and his more grounded, sometimes critical, view of the world distinguish him. He stands not just as the heir to Giambattista, but as a vital link between the late Baroque/Rococo tradition and the changing artistic sensibilities of the late 18th century. His influence can be seen less in direct stylistic imitation by later painters and more in the enduring appeal of his graphic work and his insightful portrayal of the human comedy, anticipating aspects of later artists who explored social observation and satire, like Honoré Daumier in 19th-century France. His ability to operate both within the grand tradition of decorative painting and the more intimate realm of drawing and printmaking makes him a fascinating and multifaceted figure in the history of European art. His works continue to engage viewers with their technical brilliance, narrative richness, and enduring human relevance. He remains a testament to the enduring creativity of Venetian art even in its final flowering.