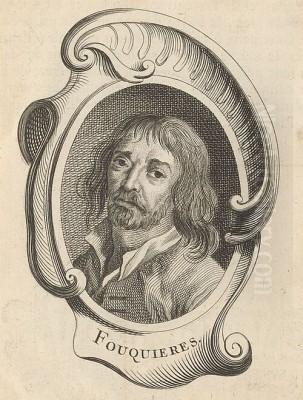

Jacques Fouquieres, a pivotal yet sometimes overlooked figure in the history of landscape painting, stands as a testament to the rich artistic cross-currents that defined 17th-century Europe. Born in Antwerp, the vibrant artistic hub of Flanders, Fouquieres absorbed the traditions of his homeland before embarking on a career that would see him work for illustrious patrons and significantly influence the development of landscape art, particularly in France. His life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the evolving status of landscape painting, its stylistic transformations, and the international network of artists and patrons that shaped the Baroque period.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Jacques Fouquieres, or Jacob Focquier as he was known in Flemish, was born in Antwerp around 1580, though some sources suggest a slightly later date, closer to 1590. Antwerp, at this time, was a city teeming with artistic talent, still basking in the legacy of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and witnessing the meteoric rise of Peter Paul Rubens. It was in this fertile environment that Fouquieres received his initial artistic training. His primary masters were two distinguished figures in the Flemish landscape tradition: Joos de Momper the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Joos de Momper (1564-1635) was renowned for his expansive, often mountainous, "world landscapes," a genre that combined fantastical elements with an increasingly naturalistic observation of terrain. His works typically featured dramatic vistas, craggy peaks, and a conventionalized color perspective, moving from brownish foregrounds to greenish mid-grounds and bluish distances. From Momper, Fouquieres would have learned the techniques of composing grand, panoramic scenes and the established formulas of Flemish landscape.

Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625), often called "Velvet" Brueghel for the smooth, refined finish of his paintings, offered a different but complementary influence. Brueghel was a master of meticulous detail, painting exquisite flower pieces, allegories, and, importantly, landscapes that were often populated with mythological or biblical figures, or scenes of everyday life. His landscapes, while still adhering to certain conventions, showed a keen observation of nature and a delicate touch. Fouquieres's association with Brueghel would have instilled in him a respect for detailed rendering and the ability to integrate figures harmoniously within a natural setting. It is a testament to Fouquieres's talent that contemporary accounts suggest he eventually surpassed both these eminent teachers in the specific domain of landscape painting, developing a style that was both rooted in this tradition and uniquely his own.

Travels and Broadening Horizons: Heidelberg and Italy

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Fouquieres did not confine his career to his native city. Before 1616, he traveled to Heidelberg, Germany, where he entered the service of Frederick V, the Elector Palatine. Frederick, who would later become tragically known as the "Winter King" of Bohemia, was a significant Protestant prince and a patron of the arts. Fouquieres's work for the Elector likely involved creating landscape paintings to adorn his palaces, and this period would have exposed him to different artistic tastes and perhaps the work of German artists.

A crucial, though less precisely dated, part of Fouquieres's development was his journey to Italy. Italy, particularly Rome, was the ultimate finishing school for Northern European artists. It was there that they could study firsthand the masterpieces of antiquity and the Italian Renaissance, and immerse themselves in the burgeoning Baroque movement. For landscape painters, the Roman Campagna, with its picturesque ruins and atmospheric light, was a powerful source of inspiration. Artists like Paul Bril, a Fleming who had established a successful career in Rome, and Adam Elsheimer, a German painter whose poetic, small-scale landscapes had a profound impact, were transforming the genre.

During his time in Italy, Fouquieres is said to have diligently studied and copied the works of the Venetian master Titian (Tiziano Vecellio, c. 1488/1490-1576). Titian, though primarily a figure painter, had produced revolutionary landscapes, both as standalone works and as backgrounds in his religious and mythological scenes. His handling of color, light, and atmosphere, particularly in his later works, offered profound lessons in creating emotive and naturalistic environments. This engagement with Titian's art undoubtedly refined Fouquieres's palette and his understanding of how to convey mood and depth in landscape. The Italian experience, combined with his Flemish training, equipped Fouquieres with a versatile and sophisticated artistic vocabulary.

The Move to France and Royal Patronage

By 1621, Jacques Fouquieres had made a significant career move, relocating to Paris. France, under King Louis XIII and his chief minister Cardinal Richelieu, was experiencing a period of cultural consolidation and artistic flourishing. Fouquieres's talent for landscape painting quickly found favor, and his reputation grew. His arrival coincided with a growing appreciation for landscape as an independent genre in France, moving beyond its traditional role as mere background for historical or religious narratives.

His skills did not go unnoticed by the highest echelons of French society. King Louis XIII himself became a significant patron. Fouquieres was granted the prestigious title of "Peintre du Roi" (Painter to the King) and was entrusted with a major commission: to paint a series of views of the principal French towns. These paintings were intended to decorate the Grande Galerie of the Louvre Palace in Paris, a project of immense cultural and political significance, designed to celebrate the kingdom of France. This ambitious undertaking required Fouquieres to travel throughout France, sketching and documenting various cities and their surrounding landscapes. While the project was ultimately never fully completed, and many of the large-scale canvases may have been lost or were never finished, the surviving sketches and related works attest to Fouquieres's dedication and his ability to capture the specific character of different locales.

His presence in Paris was also notable for attracting students. One of his most distinguished pupils during this early Parisian period was Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674). Champaigne, also of Flemish origin (born in Brussels), joined Fouquieres's studio around 1620 or 1621 and subsequently followed him to Paris. While Champaigne would become primarily known for his austere and psychologically insightful portraits and religious paintings, his early training with Fouquieres provided him with a solid grounding in landscape, elements of which often appear in the backgrounds of his later works. After his initial period with Fouquieres, Champaigne also worked in the studio of Georges Lallemant, another prominent painter in Paris.

Artistic Style and Influences

Jacques Fouquieres's artistic style is a fascinating synthesis of Northern European traditions and Italianate influences, characteristic of the Baroque era's dynamic artistic exchanges. His landscapes are typically well-structured, often featuring a foreground marked by prominent trees or a cluster of trees, which act as a repoussoir, drawing the viewer's eye into the composition. A middle ground frequently unfolds with a river, a winding path, or a gentle valley, leading the gaze towards a distant, hazy horizon where the sky meets the land. This compositional structure, common in Flemish and Dutch landscape painting, creates a sense of depth and ordered space.

The influence of his teachers, Joos de Momper and Jan Brueghel the Elder, remained evident in his attention to detail in foliage and his ability to create expansive views. However, Fouquieres developed a more naturalistic and often more monumental approach than Momper's sometimes fantastical scenes. His trees are rendered with a sense of volume and texture, and his understanding of light and shadow creates a convincing sense of atmosphere.

His Italian sojourn, particularly his study of Titian and his exposure to the work of artists like Paul Bril (1554-1626), a fellow Fleming who had become a leading landscape painter in Rome, and later, the emerging classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), refined his style. From the Italian tradition, Fouquieres absorbed a greater sense of harmony, a softer play of light, and often a more idealized vision of nature. While Poussin and Claude developed a highly structured, classical landscape, often imbued with mythological or historical gravitas, Fouquieres retained a more distinctly Northern European flavor, with a focus on the specific character of the land. His work can be seen as a bridge between the detailed naturalism of the Flemish school and the more idealized, atmospheric landscapes emerging from Italy and being adopted in France.

His palette was generally characterized by fresh, transparent colors. Some critics noted that his greens could occasionally be too dominant or his overall tone somewhat cool, but his best works achieve a delicate balance and a luminous quality. The figures that populate his landscapes – often small-scale villagers, hunters, shepherds, or travelers – are typically rendered with accuracy and a lively spirit, adding anecdotal interest and a sense of human presence within the vastness of nature. These figures are reminiscent of the staffage found in the works of Jan Brueghel the Elder or later Dutch landscapists like Lodewijk de Vadder (1605-1655), whose woodland scenes share some affinities with Fouquieres's approach to sylvan environments.

Fouquieres was also reportedly skilled in etching, a medium favored by many landscape artists for its ability to capture linear detail and atmospheric effects. While fewer of his etchings may survive or be securely attributed, this facility would have complemented his painting practice.

Key Works and Their Characteristics

Despite his contemporary fame and prolific output, a significant portion of Jacques Fouquieres's oeuvre has unfortunately been lost over the centuries, or attributions have become uncertain. However, several key works and documented projects help us understand his artistic achievements.

One of his most notable surviving paintings is Rugged Landscape with Hunters, dated around 1620 and currently housed in the Musée d'Arts de Nantes, France. This work exemplifies many characteristic features of his style. It presents a dynamic, somewhat wild landscape with prominent, gnarled trees in the foreground. A path winds through the scene, and small figures of hunters with their dogs animate the composition. The painting demonstrates his ability to combine detailed observation of nature – the texture of the bark, the rendering of foliage – with a strong compositional sense and an evocative atmosphere. The interplay of light and shadow creates a sense of depth and drama, typical of the Baroque sensibility.

The ambitious series of paintings depicting French towns, commissioned by Louis XIII for the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, though largely uncompleted or dispersed, represents a significant aspect of his career. These works were intended not just as topographical records but as celebrations of the French realm. Surviving drawings and smaller paintings related to this project show his skill in capturing the specific features of urban environments within their natural settings. This commission placed him in the tradition of artists who documented and glorified the territories of their patrons, a role that landscape painting increasingly fulfilled.

Other works attributed to Fouquieres can be found in various European collections. For instance, a smaller landscape is noted in the collection of the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Germany, and another in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, France. The Louvre in Paris, beyond the Grande Galerie project, likely holds other works, though some may be unsigned or their attribution debated, a common issue with artists of this period whose workshops often involved assistants.

His style, with its blend of Flemish detail and Italianate breadth, often featured these characteristic elements: carefully observed trees forming a screen or focal point, villages nestled in valleys, distant blue-tinged mountains, and winding rivers or roads that lead the eye through the composition, creating a pastoral and often tranquil mood. The human figures, though small, are integral, suggesting humanity's place within the broader natural world.

Collaborations, Students, and Influence on Contemporaries

Jacques Fouquieres was not an isolated figure; he was part of a vibrant artistic community, both as a recipient of influences and as a mentor. His most famous student, Philippe de Champaigne, went on to become one of the leading painters in 17th-century France, a key figure in the development of French Classicism and a founding member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Champaigne's early exposure to landscape painting under Fouquieres, even if landscape was not his primary genre, undoubtedly enriched his artistic toolkit. The backgrounds of many of Champaigne's portraits and religious scenes reveal a sophisticated understanding of landscape composition and atmospheric effects.

Another artist associated with Fouquieres as a student was Jean Morin (c. 1605/1609 – 1650). Morin later distinguished himself primarily as an engraver and printmaker, producing numerous portraits and reproductive prints after famous paintings. His training with Fouquieres would have provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and composition, essential skills for an engraver. Morin's prints often display a sensitivity to light and texture that may reflect his early studies.

Fouquieres's style also resonated with or paralleled the work of other contemporary landscape painters. His approach to woodland scenes, with their emphasis on the textures of trees and the play of light through leaves, can be compared to the work of other Flemish artists like Abraham Govaerts (1589-1626) or Alexander Keirincx (1600-1652), who also specialized in forest landscapes. The broader European context included artists like the aforementioned Rudolf van der Veldt, whose works shared certain stylistic similarities.

His move to Paris was significant because it brought a highly skilled Flemish landscape specialist directly into the French artistic milieu. At a time when French landscape painting was still finding its distinct voice, Fouquieres provided a powerful example of the sophisticated landscape traditions of the Low Countries, enriched by Italian experience. He, along with other Northern artists active in Paris, contributed to a growing taste for naturalistic and evocative landscapes among French patrons. His work can be seen as a precursor to the more overtly classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, who, although developing in different directions, also benefited from the increasing status and appreciation of landscape art to which Fouquieres contributed. Even the great Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), primarily a figure painter, produced magnificent landscapes later in his career, demonstrating the genre's appeal among the leading masters of the age. Fouquieres was sometimes even referred to as the "Flemish Rubens of landscape," highlighting his perceived stature in this specific field.

Later Years and Legacy

Despite his early successes and royal patronage, Jacques Fouquieres's later life seems to have been marked by a decline in fortune. Historical records suggest that he died in Paris in 1659, reportedly in poverty. The reasons for this change in circumstances are not entirely clear. Perhaps the ambitious Grande Galerie project, being unfinished, led to financial difficulties, or perhaps tastes shifted, or personal issues intervened. One anecdotal account mentions a period spent in Provence where he may have indulged excessively in "drinking and entertainment," though the reliability of such biographical details from early sources can be variable.

Regardless of his personal fortunes at the end of his life, Fouquieres left a tangible legacy. He played a crucial role in popularizing and elevating landscape painting in France. His synthesis of Flemish naturalism with an Italianate sense of grandeur and atmosphere provided a model that was both sophisticated and accessible. He demonstrated that landscape could be a subject worthy of major royal commissions and serious artistic endeavor.

His influence can be seen in the work of his direct pupils like Philippe de Champaigne and Jean Morin, but also more broadly in the increasing prominence of landscape elements in French art of the 17th century. He helped pave the way for the next generation of French landscape painters, who would build upon these foundations to create a distinctly French school of landscape art. Artists like Laurent de La Hyre (1606-1656), for example, developed a lyrical and classical style of landscape that, while different from Fouquieres, was part of this broader flourishing of the genre.

Though many of his works are lost, those that survive, along with contemporary accounts, confirm his skill and importance. He was a transitional figure, bridging the late Mannerist and early Baroque landscape traditions of Flanders with the emerging classical and naturalistic trends in Italy and France. His ability to create landscapes that were both observant of natural detail and imbued with a sense of poetic harmony ensured his place in the story of European art.

Fouquieres in the Context of Baroque Landscape Painting

To fully appreciate Jacques Fouquieres, it is essential to view him within the broader context of Baroque landscape painting. The 17th century witnessed an explosion of landscape art across Europe. In the Dutch Republic, artists like Jacob van Ruisdael, Meindert Hobbema, and Aelbert Cuyp captured the specific light and terrain of their homeland with unprecedented naturalism. In Flanders, alongside Rubens, artists like Jan Wildens and Lucas van Uden continued the tradition of dynamic, often lush landscapes.

In Italy, the idealized, classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, both Frenchmen working primarily in Rome, set a standard for centuries to come. These artists, along with Italian painters like Salvator Rosa, who specialized in wild, romantic scenes, explored the expressive potential of nature in diverse ways. Paul Bril, an earlier Fleming in Rome, had already shown how Northern artists could adapt to and influence the Italian scene.

Fouquieres fits into this complex tapestry as an artist who successfully navigated these different national traditions. He brought the strengths of his Flemish training – strong composition, detailed observation, and a love for the textures of the natural world – to new contexts. His work in Germany and particularly his extended period in France, coupled with his Italian studies, made him an international figure. He was less overtly dramatic than some of his Dutch contemporaries, and less rigorously classical than Poussin or Claude, carving out a niche for landscapes that were at once naturalistic, picturesque, and imbued with a gentle, pastoral charm. His contribution was vital in disseminating a sophisticated approach to landscape beyond the confines of the Low Countries, particularly in France, where the genre was on the cusp of a major efflorescence.

Conclusion

Jacques Fouquieres was a significant landscape painter of the Baroque era, a master whose career spanned several important artistic centers and who absorbed and synthesized diverse influences. From his rigorous training in Antwerp under Joos de Momper and Jan Brueghel the Elder, he developed a profound understanding of landscape composition and natural detail. His travels to Germany and Italy, especially his study of Titian, broadened his artistic vision, infusing his work with a greater sense of atmosphere and harmony.

His move to Paris marked a crucial phase, where he gained royal patronage from Louis XIII and undertook ambitious projects like the views of French towns for the Louvre. He played an important role in the development of French landscape painting, influencing students like Philippe de Champaigne and contributing to the genre's rising prestige. Though many of his works are lost and his later years were shadowed by hardship, his surviving paintings, such as Rugged Landscape with Hunters, attest to his skill in creating evocative and beautifully rendered natural scenes. Jacques Fouquieres remains a key figure for understanding the rich and complex evolution of landscape art in 17th-century Europe, an artist who skillfully blended Northern realism with Southern European idealism.