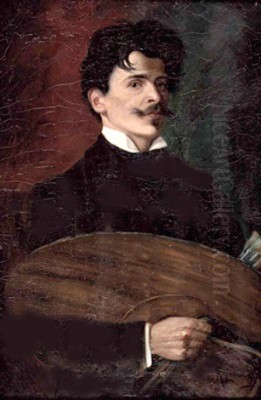

Jakob Koganowsky (1874-1926) emerges from the annals of art history as a figure whose life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the vibrant artistic currents of Central Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. Born in Kyiv, then part of the Russian Empire, Koganowsky would later make Vienna his home and primary center of artistic creation. His oeuvre, though not as widely celebrated today as some of his contemporaries, showcases a dedicated artist skilled in various genres, most notably still life and animal painting, alongside intriguing forays into mythological and illustrative work that hint at his rich cultural heritage.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Munich

The foundational years of an artist often dictate the trajectory of their career, and for Jakob Koganowsky, his formal training began in a city renowned for its academic rigor and burgeoning modernist impulses: Munich. From 1899, Koganowsky was enrolled at the Munich Academy of Art (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). This institution was a crucible of artistic talent, attracting students from across Europe and beyond. During this period, the Academy was still under the influence of the "Munich School" painters of the 19th century, known for their dark palettes and painterly realism, figures like Wilhelm Leibl and Franz von Lenbach had set a high standard.

However, by the time Koganowsky arrived, new winds were blowing. Franz von Stuck, a co-founder of the Munich Secession in 1892 and a professor at the Academy from 1895, was a dominant figure. Stuck's work, deeply imbued with Symbolism and often drawing on mythological themes, would have provided a powerful counterpoint to more traditional academic training. Other influential teachers and artists associated with Munich at this time included Wilhelm von Diez, known for his genre and animal paintings, and Ludwig von Löfftz. The city was also a center for Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau, which emphasized decorative forms and organic lines, championed by artists like August Endell and Hermann Obrist. Koganowsky's time in Munich would undoubtedly have exposed him to these diverse influences, shaping his technical skills and artistic vision.

Vienna: A Crucible of Modernity

After his studies in Munich, Koganowsky established himself in Vienna. The Austro-Hungarian capital at the turn of the century was an unparalleled center of intellectual and artistic innovation. This was the Vienna of Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. In the visual arts, it was the era of the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by a group of artists, including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, who broke away from the conservative Association of Austrian Artists. The Secession championed a new, modern art, embracing international styles like Art Nouveau and Symbolism, and promoting the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

While there is no direct evidence placing Koganowsky within the inner circles of the Secession, living and working in Vienna during this period meant being immersed in its revolutionary artistic atmosphere. The exhibitions of the Secession, the groundbreaking designs of the Wiener Werkstätte (co-founded by Moser and Hoffmann in 1903), and the emerging talents of younger artists like Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, who would soon push Viennese art towards Expressionism, created a dynamic environment. Koganowsky’s work, particularly his focus on detailed observation and his later illustrative pieces, suggests an artist absorbing these currents while perhaps maintaining a more personal, less overtly avant-garde path.

The Intimate World of Still Life

Jakob Koganowsky’s primary artistic reputation rests on his skill as a still life painter. This genre, with its long and distinguished history stretching back to the Dutch Golden Age masters like Willem Kalf and Pieter Claesz, and revitalized in the 19th century by artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and Henri Fantin-Latour, offered Koganowsky a canvas for exploring form, color, texture, and composition. His still lifes are characterized by a meticulous attention to detail and a deep appreciation for the humble beauty of everyday objects and natural elements.

His subject matter within this genre was remarkably diverse. He painted delicate "small wild flowers," capturing their ephemeral charm. His canvases featured arrangements of "flowers, butterflies, birds," evoking a sense of nature brought indoors. More robust subjects included "melons and fruits," a classic theme allowing for the exploration of vibrant colors and varied textures. One of his known works is titled precisely this: Melons and Fruits . The inclusion of "azaleas" points to an interest in cultivated beauty, while "peaches in a red glass bowl" suggests a sophisticated play of light, reflection, and color harmony, reminiscent of the rich still lifes of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne or Vincent van Gogh, who also found profound meaning in such subjects.

Koganowsky’s still lifes also extended to more unconventional items. The mention of "snowflake parquet floors" as a subject or perhaps a recurring background element is intriguing, suggesting an interest in pattern and domestic interior spaces. "Kitchen style" implies a focus on the rustic charm of culinary settings, perhaps including "kettles" and other utilitarian objects. More enigmatic are subjects listed as "whistles," "historical determinists," "antique cacti," "irises," "snails," and "parrots." While irises, snails, and parrots fit within a broader tradition of nature studies, "historical determinists" is a particularly unusual descriptor for a still life element, perhaps hinting at symbolic objects imbued with historical or philosophical meaning, or even a mistranslation of a more conventional subject. The "antique cacti" suggest an interest in the exotic and the enduring.

A Keen Eye for the Animal Kingdom

Beyond the realm of inanimate objects, Koganowsky demonstrated a significant talent for animal painting. It is noted that his artistic strength lay not in "hard green landscapes" but rather in the "vivid depiction of animals." This suggests a dynamic, empathetic approach to capturing the essence of his animal subjects. Specifically, he was adept at portraying "cows, goatherds, and sheep." These subjects connect him to a long tradition of pastoral art and animal portraiture, from Paulus Potter in the 17th century to 19th-century animaliers like Rosa Bonheur.

His ability to render these creatures vividly implies careful observation of their anatomy, movement, and character. In the context of early 20th-century art, where artists like Franz Marc (a key figure of Der Blaue Reiter, also with Munich connections) were exploring animals as symbols of spiritual purity and primal energy, Koganowsky’s approach seems to have been more rooted in realistic representation, though imbued with a clear appreciation for their inherent vitality. The depiction of domestic farm animals also speaks to a connection with rural life, perhaps a nostalgic echo of his Ukrainian origins or a reflection of the Austrian countryside.

Myth, Illustration, and Cultural Identity

Koganowsky’s artistic output was not confined to still life and animal studies. A significant work from 1901, created using pencil, ink, and charcoal and existing in two dimensions (38 x 28 cm and 39.5 x 50 cm), is described as a "detailed illustration of a Ukrainian Judeo-Germanic mythological scene." This piece is particularly revealing. It points to Koganowsky’s engagement with his complex cultural heritage – Jewish, Ukrainian, and working within a Germanic artistic sphere. The choice of a mythological subject, rendered with detailed precision, aligns with Symbolist tendencies prevalent at the time, where artists often delved into folklore, legends, and esoteric themes to explore deeper psychological or spiritual truths. Artists like Odilon Redon in France or Max Klinger in Germany were masters of such imaginative realms.

The specificity of a "Ukrainian Judeo-Germanic" myth suggests a unique synthesis, perhaps drawing on folk tales or religious narratives specific to the Ashkenazi Jewish experience in Eastern and Central Europe, intertwined with broader Germanic or Slavic mythological elements. This work, created relatively early in his Vienna period after his Munich studies, indicates an artist exploring themes of identity and storytelling through a meticulous graphic style. Another illustrative work mentioned is a depiction of "four Ottomans," which further broadens his thematic range, possibly reflecting an interest in Orientalist themes or historical subjects, a common fascination in 19th and early 20th-century European art, seen in the works of artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Ludwig Deutsch.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Legacy

Synthesizing the available information, Jakob Koganowsky appears as an artist of considerable technical skill and diverse interests. His training at the Munich Academy would have provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and painting. His illustrative works, like the mythological scene, demonstrate proficiency in pencil, ink, and charcoal, suggesting a fine hand and an eye for detail. His still lifes, with their varied subjects from delicate flowers to robust fruits and intriguing curiosities, indicate a versatile painterly technique capable of capturing different textures, colors, and light effects. The praise for his "vivid depiction of animals" suggests a capacity for dynamic composition and an ability to convey life and movement.

Despite his evident talent and activity in major artistic centers, information regarding Jakob Koganowsky’s exhibitions or his direct participation in prominent artistic groups in Vienna remains elusive from the provided sources. This is not uncommon for artists who may have focused on private commissions, smaller group shows, or whose records have become obscured over time. The art world of Vienna was vast, and not every artist achieved the lasting fame of a Klimt or Schiele, yet figures like Koganowsky contributed to the rich tapestry of the city's cultural life. Other Viennese artists of the period, perhaps less internationally renowned but significant locally, included painters like Carl Moll, a Secessionist who also excelled in landscapes and still lifes, or Tina Blau, known for her atmospheric landscapes.

Koganowsky’s art, particularly his still lifes with their eclectic mix of subjects – from the conventional beauty of "small flowers" and "azaleas" to the more unusual "antique cacti" or the enigmatic "historical determinists" – and his powerful animal portrayals, offers a window into the sensibilities of an artist navigating the transition from 19th-century traditions to early 20th-century modernism. His work seems to embody a quiet dedication to craft and a personal vision, finding beauty and significance in the observed world and in the echoes of cultural heritage.

Conclusion: An Artist Worthy of Renewed Attention

Jakob Koganowsky (1874-1926) represents a fascinating strand in the complex web of European art at the turn of the century. Born in Kyiv, trained in Munich, and active in Vienna, he was geographically and artistically positioned at a crossroads of cultures and styles. While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the leading avant-gardists, his commitment to the genres of still life and animal painting, executed with evident skill and sensitivity, marks him as a noteworthy artist. His illustrative work, particularly the "Ukrainian Judeo-Germanic mythological scene," offers tantalizing clues to a deeper engagement with personal and cultural identity.

His diverse still life subjects, ranging from "melons and fruits" to "butterflies" and "parrots," alongside his strong depictions of "cows, goatherds, and sheep," place him in a lineage of artists dedicated to the careful observation and representation of the world around them. He worked in an era alongside giants like Claude Monet, who also explored still life, and contemporaries in Vienna who were reshaping the very definition of art. While the full scope of his career, including exhibitions and specific interactions with other artists like perhaps the animal painter Heinrich von Zügel (also active in Munich), remains to be fully illuminated, the existing evidence paints a picture of a dedicated and talented artist. Jakob Koganowsky’s work merits further study and appreciation, offering a nuanced perspective on the artistic life of Vienna and Munich during a period of profound transformation.