Max Liebermann stands as a towering figure in German art history, a pivotal artist who navigated the transition from 19th-century Realism to the burgeoning modernism of the 20th century. Born in Berlin in 1847 and passing away in the same city in 1935, his life spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic upheaval in Germany and Europe. Liebermann was not merely a painter and printmaker; he was a cultural force, an organizer, a collector, and a leading proponent of Impressionism in Germany, often grouped with Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt as the primary exponents of the style within the country. His journey reflects both the artistic innovations of his time and the tragic shadows cast by rising antisemitism and the Nazi regime.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Max Liebermann was born into a prosperous Jewish industrialist family in Berlin. His upbringing was one of privilege, but his path was not initially set towards art. Following the expectations typical for his social class, he first enrolled at the University of Berlin to study law and philosophy. However, the allure of the visual arts proved stronger than familial expectations or academic pursuits. His passion for drawing and painting soon led him to abandon his initial studies, a decision likely met with some resistance from his family who might have envisioned a more conventional career for him.

His formal artistic training began in earnest around 1866 when he started taking lessons from the Berlin painter Carl Steffeck. Steffeck, known primarily for his battle scenes and equestrian portraits, recognized Liebermann's talent and encouraged him to pursue art seriously. This initial mentorship provided Liebermann with foundational skills and, crucially, the validation to commit fully to an artistic life, setting him on a course that would diverge significantly from his family's commercial background.

Formative Years: Weimar, Paris, and the Netherlands

Seeking more rigorous and structured training, Liebermann moved to Weimar in 1868 to study at the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School (Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule Weimar). He remained there until 1872, studying under notable artists such as the Belgian history painter Ferdinand Pauwels and later Karel Verlat. The atmosphere in Weimar was relatively liberal compared to the more rigid academies elsewhere, allowing students a degree of freedom to develop their individual styles. It was during this period that Liebermann began to gravitate towards Realism, focusing on depictions of everyday life, particularly rural labor.

A pivotal moment in his early career came through his encounter with the work of the Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy. Munkácsy's dramatic realism and dark palette, particularly in his depictions of peasant life, deeply impressed Liebermann and helped him solidify his own artistic direction, moving away from purely academic conventions towards a more direct and unvarnished portrayal of reality. This influence contributed to his growing independence as an artist.

In 1873, Liebermann relocated to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world at the time. This move exposed him directly to the revolutionary currents transforming French art. He spent considerable time studying the works of Realist masters like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, whose sympathetic portrayals of peasant life resonated with Liebermann's own interests. He also admired the Dutch Golden Age masters, particularly Frans Hals, whose lively brushwork and psychological insight were influential.

Crucially, his time in Paris coincided with the rise of Impressionism. Liebermann encountered the works of Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, absorbing their innovative approaches to light, color, and capturing fleeting moments. While he never fully adopted the broken color techniques of the French Impressionists, their emphasis on observing contemporary life and the effects of light profoundly impacted his development. He also spent time associated with artists of the Barbizon School, learning the importance of painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture natural light and atmosphere directly.

Further enriching his experience, Liebermann made extended visits to the Netherlands starting in the mid-1870s. He was drawn to the Dutch landscape, the quality of light, and the traditions of Dutch art. He spent summers there, painting scenes of rural life, orphanages, and coastal views. His time in Holland connected him with artists of the Hague School, such as Jozef Israëls, whose sober realism and atmospheric depictions of peasant and fisherfolk life reinforced Liebermann's own thematic concerns while subtly lightening his palette and loosening his brushwork.

The Emergence of a German Impressionist

Returning to Germany in 1878, Liebermann initially settled in Munich before moving back to his native Berlin in 1884. He brought with him the diverse influences gathered during his years abroad, particularly the lessons learned from French Realism, Impressionism, and the Dutch masters. He began to forge a distinct style that blended realistic subject matter – often focusing on the lives of workers, peasants, and the urban poor – with an increasingly impressionistic handling of light and color.

One of his first major works, completed during his Weimar years but exhibited later, was Women Plucking Geese (Gänserupferinnen), finished in 1872. When shown, this painting caused a stir due to its stark, unidealized depiction of working women engaged in a messy task. Critics, accustomed to more polished academic art, were shocked by its realism, with some derisively labeling Liebermann an "apostle of ugliness." This early controversy highlighted his commitment to depicting life truthfully, even if it challenged conventional tastes.

Another significant work from this period is The Flax Spinners (Die Flachspinnerinnen) from 1887. This large canvas depicts women working diligently in a dimly lit interior in Laren, Netherlands. While still rooted in realism, the painting shows a greater sensitivity to atmosphere and the play of light filtering through the windows, hinting at the impressionistic tendencies that would become more pronounced in his later work. The mood is somber and reflective, typical of his depictions of labor during this phase.

These early works established Liebermann's reputation as a powerful, albeit sometimes controversial, modern artist in Germany. He was seen as a painter who tackled contemporary social themes with honesty and technical skill, challenging the prevailing historical and mythological subjects favored by the official art establishment.

Masterworks and Stylistic Evolution

From the 1890s onwards, Liebermann's style evolved significantly towards Impressionism. Influenced by his continued engagement with French art, particularly the works of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, his palette brightened considerably, his brushwork became looser and more visible, and his focus shifted increasingly towards capturing the effects of light and atmosphere. While he retained an interest in depicting people, his subjects often expanded to include scenes of bourgeois leisure, gardens, street life, and portraits.

His move to Berlin in 1884 marked a turning point. He became a prominent figure in the city's cultural life. His own garden at his villa in Wannsee, on the outskirts of Berlin, became a frequent subject, particularly in his later years. Paintings like Garden in Wannsee (Garten in Wannsee), produced in numerous variations especially after 1915, showcase his mature impressionistic style. These works are characterized by vibrant colors, dappled sunlight filtering through foliage, and a sense of tranquil domesticity, often compared to Monet's Giverny paintings.

Works like Parrot Man (Papageienmann) from 1902 exemplify his engagement with urban scenes and brighter colors. It captures the lively atmosphere of an Amsterdam zoo or street scene with energetic brushstrokes and a keen eye for capturing a specific moment in time. Similarly, A National Restaurant, Brannenburg, Bavaria (Biergarten in Brannenburg) from 1894 depicts a bustling beer garden scene, skillfully rendering the interplay of light and shadow under the trees and capturing the social dynamics of leisure.

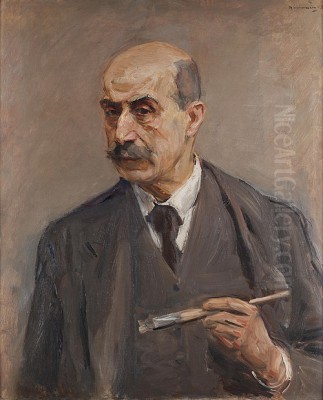

Throughout this period, Liebermann also became a highly sought-after portrait painter. He painted numerous prominent figures in German society, including scientists, artists, politicians, and industrialists. His portraits are noted for their psychological insight and lack of flattery, rendered with the same vigorous brushwork and attention to light that characterized his other works. Even in seemingly simple domestic scenes like Woman with a Cat (Frau mit Katze), his ability to observe and render everyday moments with sensitivity and painterly skill is evident.

His evolution was not a complete abandonment of realism but rather a synthesis. He integrated the impressionistic concern for light and momentary effects with a solid grounding in drawing and composition derived from his earlier training and his admiration for Old Masters like Hals. This unique blend defined German Impressionism and distinguished it from its French counterpart.

The Berlin Secession: A Force for Modernism

Max Liebermann was not content to merely paint; he was also deeply involved in the organizational and political aspects of the art world. By the late 1890s, the official art establishment in Berlin, dominated by the conservative Association of Berlin Artists and the Prussian Academy of Arts (Preußische Akademie der Künste), was perceived by many younger, more progressive artists as stifling and resistant to new trends, particularly Impressionism and Jugendstil (Art Nouveau).

In response, Liebermann, along with fellow artist Walter Leistikow and others, spearheaded the formation of the Berlin Secession (Berliner Secession) in 1898, officially established in early 1899. Liebermann was elected its first president, a position he held until 1911. The Secession aimed to provide an alternative exhibition venue free from the constraints of the official Salon system and its jury, which often rejected more modern works. It championed artistic freedom and quality, regardless of style or status.

Under Liebermann's leadership, the Berlin Secession quickly became the most important forum for modern art in Germany. It organized regular exhibitions showcasing not only the work of its German members – including Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Käthe Kollwitz, and Edvard Munch (who lived in Berlin at the time) – but also major international artists. French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Cézanne, and Van Gogh were featured prominently, exposing the German public and artists to the latest developments in European art.

The Secession was a critical force in breaking the dominance of academic art in Germany and paving the way for subsequent modernist movements like Expressionism (though Liebermann himself had reservations about the Expressionists). His role as president cemented his status as a leader of the avant-garde in Germany, a respected figure who could bridge the gap between artistic innovation and public acceptance.

Leadership and Recognition

Liebermann's influence extended beyond the Secession. His artistic achievements and leadership qualities earned him widespread recognition. In 1897, he was awarded the title of Professor by the Prussian government, and he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts. His relationship with the Academy was complex; while he was a member, he was also the driving force behind the Secession, which stood in opposition to the Academy's conservative tendencies.

However, his stature grew to such an extent that in 1920, he was elected President of the Prussian Academy of Arts itself. He held this prestigious position until 1932/33. This appointment signaled a significant shift in the German art establishment, acknowledging the importance of the modern art movements that Liebermann had championed for decades. As president, he oversaw a period where the Academy became more open to diverse artistic styles. He was a respected, if sometimes autocratic, leader within the German cultural landscape, receiving numerous honors and commissions throughout the Weimar Republic era.

Liebermann the Collector

Parallel to his career as a painter and arts administrator, Max Liebermann was also an avid and astute art collector, particularly of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. Using the considerable wealth inherited from his family, he assembled one of the most important collections of modern French art in Germany before World War I.

His collection included significant works by Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Gustave Courbet, among others. He acquired masterpieces such as Manet's The Asparagus and several works by Degas. This activity was not merely a private passion; it was integral to his role as a cultural mediator. By acquiring and living with these works, Liebermann deepened his own understanding of French modernism and implicitly promoted these styles within Germany.

His villa in Wannsee housed much of this collection, making it a site of cultural pilgrimage for artists and critics. His collecting activities helped to shape German taste and encouraged other German collectors and museums to acquire modern French art. This played a crucial role in internationalizing the German art scene and fostering a dialogue between German and French artists. Unfortunately, much of this collection was later dispersed or looted during the Nazi era.

Controversies and Challenges

Liebermann's career was marked by several controversies, reflecting both the provocative nature of his art and the turbulent times he lived in. His early realistic works, like Women Plucking Geese, drew criticism for their perceived ugliness and focus on common labor.

A more significant controversy erupted over his painting The Twelve-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple (Der zwölfjährige Jesus im Tempel), first exhibited in 1879 at the Munich International Art Exhibition. The painting depicted a young, arguably Semitic-looking Jesus debating earnestly with Jewish elders in the temple. It provoked outrage from both Christian and Jewish circles. Christians objected to what they saw as an undignified, overly human portrayal of Jesus, while some critics deployed antisemitic tropes, accusing Liebermann of depicting Jesus as a "galley boy" and the elders as "dirty hagglers." The controversy reached the Bavarian parliament. Liebermann was deeply affected and later repainted the figure of Jesus to appear more conventionally Aryan, though the work remained a painful point in his career, highlighting the complex intersection of art, religion, and antisemitism in Imperial Germany.

His leadership of the Berlin Secession also involved internal conflicts, particularly as younger artists, including the Expressionists of Die Brücke, began to challenge the dominance of Impressionism. Liebermann famously clashed with artists like Emil Nolde, leading to splits within the Secession. While he championed modernism against academic conservatism, he found it harder to embrace the radical departures of the next generation.

Furthermore, throughout his life, Liebermann navigated the complexities of being a prominent Jew in German society. While he achieved immense success and integration into the cultural elite, underlying antisemitic currents were always present and would ultimately lead to his tragic marginalization in his final years.

The Darkening Shadow: The Nazi Era

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a devastating end to Liebermann's public life and recognition. As a Jew, he was immediately targeted by the new regime's antisemitic policies. He was forced to resign from his position as President of the Prussian Academy of Arts. He also withdrew his paintings from exhibition in protest against the Academy's decision to no longer exhibit works by Jewish artists.

His art, along with that of many other modernists (including Corinth, Slevogt, Nolde, and Kollwitz), was declared "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst) by the Nazis. His works were removed from German museums, and some were included in the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937, designed to ridicule modern art. He was effectively banned from working and exhibiting in Germany.

Liebermann spent his final years in increasing isolation in his Berlin home near the Brandenburg Gate. He witnessed the beginning of the brutal persecution of Jews in Germany. A famous, possibly apocryphal, anecdote recounts him watching a Nazi torchlight parade celebrating Hitler's rise to power from his window and remarking, "I cannot possibly eat as much as I would like to vomit." ("Ich kann gar nicht so viel fressen, wie ich kotzen möchte.")

His wife, Martha Liebermann, faced continued persecution after his death. To avoid deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, she took her own life in 1943. Max Liebermann died in Berlin on February 8, 1935, spared the worst horrors of the Holocaust but having witnessed the destruction of the liberal, cultured Germany he had represented and helped to build. His funeral was sparsely attended, as many colleagues feared repercussions for associating with a prominent Jew. Only a few brave friends, like Käthe Kollwitz, dared to attend.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the tragic circumstances of his final years and the Nazi attempts to erase his contribution, Max Liebermann's importance in German art history is undeniable. He was a crucial figure in introducing and adapting Impressionism for a German context, creating a distinct national variant of the style. His work successfully bridged the gap between 19th-century Realism and 20th-century Modernism.

As a leader of the Berlin Secession and President of the Prussian Academy of Arts, he played a vital role in reforming German art institutions and promoting artistic freedom. His advocacy for modern art, both German and international, broadened horizons and challenged entrenched academic traditions. His extensive collection of French Impressionist art further enriched Germany's cultural landscape.

After World War II, Liebermann's reputation was gradually restored. His works were returned to museums, and his significance was re-evaluated. His villa and garden in Wannsee, which survived the war, were eventually restored and opened to the public as the Liebermann Villa museum, dedicated to his life and work, and serving as a poignant memorial site.

Today, Max Liebermann is celebrated as one of Germany's greatest modern artists. His paintings, drawings, and prints are admired for their technical skill, their sensitive depiction of light and atmosphere, and their insightful portrayal of human life across different social strata – from Dutch peasant women and orphans to Berlin's bourgeoisie at leisure and portraits of the era's leading figures. He remains a symbol of artistic integrity and a testament to the vibrant cultural life of Berlin before the catastrophe of Nazism, as well as a reminder of the devastating impact of persecution on art and artists. His legacy endures in his art and in the institutions he helped shape, securing his place as a key protagonist in the story of German modern art.