James Abbott McNeill Whistler stands as a pivotal figure in nineteenth-century art, an American expatriate whose influence resonated across continents and artistic movements. Born in the United States but spending most of his productive life in London and Paris, Whistler became a leading proponent of the Aesthetic Movement and the doctrine of "Art for Art's Sake." His work, encompassing painting, etching, and interior design, challenged Victorian sensibilities and paved the way for modern art through its emphasis on formal harmony and evocative mood over narrative content. Known for his sharp wit, distinctive persona, and groundbreaking art, Whistler remains an endlessly fascinating and influential artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born on July 11, 1834, in Lowell, Massachusetts. His father, George Washington Whistler, was a prominent civil engineer, and his mother was Anna Matilda McNeill. The family's circumstances led them abroad during Whistler's formative years. In 1843, they moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, where George Whistler was employed to engineer the railway line between St. Petersburg and Moscow. It was in Russia that the young Whistler received his first formal art lessons, studying drawing and painting at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts.

This cosmopolitan upbringing exposed Whistler to different cultures early on, but his path to becoming a full-time artist was not direct. Following his father's death in 1849, the family returned to America. In 1851, Whistler secured an appointment to the prestigious United States Military Academy at West Point. However, his temperament proved ill-suited to military discipline. Famously poor marks in chemistry ("Had silicon been a gas," he later quipped, "I would have been a major general") and a general disregard for regulations led to his dismissal in 1854.

After leaving West Point, Whistler briefly worked for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey in Washington, D.C., where he honed his skills in the precise techniques of etching and mapmaking. This experience proved invaluable for his later career as a printmaker. However, his artistic ambitions soon drew him to the epicenter of the art world: Paris. In 1855, Whistler sailed for Europe, determined to pursue a career as an artist, never to return permanently to his native country.

Parisian Connections and Realism

Arriving in Paris in 1855, Whistler immersed himself in the bohemian atmosphere of the Latin Quarter. He enrolled briefly at the Ecole Impériale et Spéciale de Dessin before joining the studio of the Swiss academic painter Charles Gleyre. Gleyre's atelier was a hub for aspiring artists, and although Whistler reportedly found the formal instruction stifling, it was here that he likely encountered fellow students who would become key figures in Impressionism, possibly including Claude Monet and others.

More significant were the connections Whistler forged outside the academy. He quickly fell in with the circle around Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of the Realist movement. Courbet's emphasis on depicting contemporary life and his rejection of academic idealism profoundly influenced Whistler's early work. Whistler also formed lasting friendships with artists like Henri Fantin-Latour and Alphonse Legros. Through Fantin-Latour, he met Édouard Manet, whose own challenges to artistic convention resonated with Whistler's developing ideas.

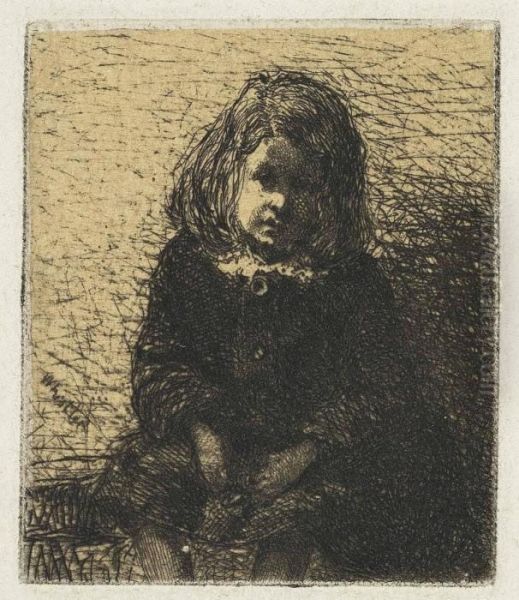

During this period, Whistler produced his first significant set of etchings, known as the "French Set," which captured scenes of everyday life with a directness inspired by Realism. His early paintings, such as At the Piano (1859), also show the influence of Courbet and Dutch masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer in their tonal subtlety and focus on domestic interiors. However, even in these early works, a distinctive elegance and concern for formal arrangement hinted at the direction his art would later take.

London Calling: A New Direction

Despite his immersion in the Parisian art scene, Whistler's relationship with the official art establishment was often fraught. After his painting Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl was rejected by the Paris Salon in 1863 (it was later shown at the controversial Salon des Refusés alongside Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe), Whistler began spending more time in London. He had already established connections there, and by 1859, he had largely relocated, finding the city's atmosphere and subjects—particularly the River Thames—more conducive to his evolving artistic vision.

In London, Whistler continued to develop his skills as an etcher, producing the celebrated "Thames Set." These works captured the industrial riverfront, its bridges, and its atmospheric conditions with unprecedented sensitivity and technical brilliance. He moved away from the explicit realism of Courbet towards a more suggestive and atmospheric style. His paintings also began to shift, showing influences from 17th-century Spanish painting, particularly the work of Diego Velázquez, in their limited palettes and elegant compositions.

London became Whistler's primary base for the remainder of his life, although he maintained strong ties with Paris. He became a prominent, if often controversial, figure in the London art world, known for his flamboyant personality, sharp wit, and increasingly radical artistic ideas. He cultivated relationships with patrons, critics, and fellow artists, establishing himself as a central figure in the burgeoning avant-garde movements.

The Aesthetic Movement and "Art for Art's Sake"

Whistler became a leading exponent of the Aesthetic Movement, which flourished in Britain during the latter half of the 19th century. Central to this movement was the doctrine of "Art for Art's Sake" (l'art pour l'art), a philosophy Whistler championed vigorously. He argued that art should be independent of any moral, didactic, or narrative purpose. Its value, he insisted, lay solely in its formal qualities—its beauty, harmony, and composition.

This philosophy directly challenged the prevailing Victorian taste, championed by critics like John Ruskin, which often demanded that art convey uplifting stories or moral lessons. Whistler believed that the subject matter of a painting was secondary to its execution. He famously began giving his works musical titles—"Symphonies," "Arrangements," "Harmonies," and "Nocturnes"—to emphasize their abstract qualities and their focus on the harmonious interplay of color and form, akin to the structure of music.

His portrait Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (1871), universally known as Whistler's Mother, exemplifies this approach. While depicting his mother, Whistler insisted the painting's primary interest lay in its formal composition—the arrangement of shapes and tones. Similarly, his Symphony in White series explored subtle variations within a limited palette, focusing on texture, light, and design rather than storytelling. This radical emphasis on aesthetics laid crucial groundwork for later developments in abstract art.

Japonisme and Cross-Cultural Dialogue

A significant influence on Whistler's art and the Aesthetic Movement in general was the influx of Japanese art and design into Europe following the reopening of Japan to the West in the 1850s. Whistler was among the earliest and most enthusiastic collectors and admirers of Japanese prints (ukiyo-e), porcelain, fans, and textiles. He recognized in Japanese art a sophisticated aesthetic sensibility that prioritized asymmetry, flattened perspectives, decorative patterns, and compositional elegance—principles that resonated deeply with his own artistic aims.

This fascination, known as Japonisme, permeated Whistler's work. It can be seen in the compositional structures of his paintings and prints, often employing high horizons, cropped forms, and asymmetrical arrangements reminiscent of artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige. His use of delicate color harmonies and flattened space also reflects Japanese influence. Works like La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine (1863-65) and the decorative motifs in his portraits explicitly incorporate Japanese elements.

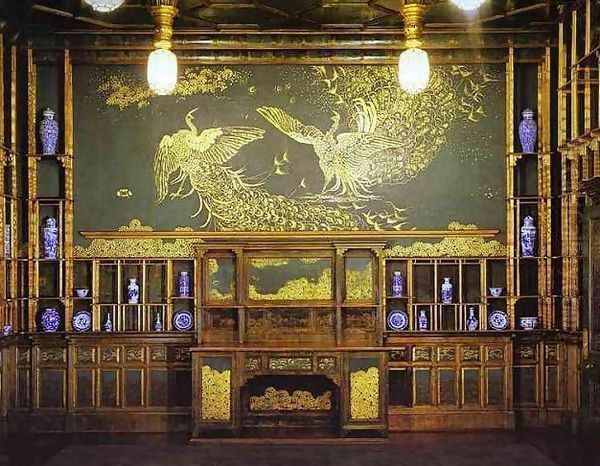

Perhaps the most spectacular manifestation of Whistler's engagement with Japonisme was Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1876-77). Originally commissioned by the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland simply to house his collection of Chinese porcelain and Whistler's Princesse, Whistler transformed the dining room into a total work of art. He covered the walls with intricate patterns of golden peacocks on a rich blue-green ground, creating an immersive environment that synthesized European and Asian aesthetics. This project, however, also led to a bitter dispute with Leyland over payment and artistic control.

Masterworks: Portraits and Nocturnes

Whistler excelled in two distinct genres that perfectly encapsulated his artistic theories: portraiture and the landscape "Nocturnes." His portraits were rarely conventional likenesses; instead, he treated his sitters as elements within a carefully constructed formal "Arrangement." He often posed his subjects standing, full-length, against minimalist backgrounds, emphasizing silhouette and tonal harmony. Famous examples include the aforementioned Whistler's Mother, the portrait of the historian Thomas Carlyle (Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2, 1872-73), and portraits of patrons like Frederick Leyland and Cicely Alexander.

These portraits, while often capturing a subtle psychological presence, prioritize aesthetic concerns. The Symphony in White series, particularly No. 1: The White Girl (1862) and No. 2: The Little White Girl (1864), showcase his mastery of subtle tonal variations and his interest in decorative surfaces, incorporating elements of Japonisme and Pre-Raphaelite influence. They are studies in mood and form as much as depictions of individuals.

The "Nocturnes," primarily painted in the 1870s, represent perhaps Whistler's most radical contribution. These were atmospheric depictions of the Thames at twilight or night, rendered in thin washes of paint that blurred forms and emphasized color harmony and mood. Works like Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75) and Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket (1875) dissolved concrete reality into near-abstract patterns of light and color. They aimed to capture the ephemeral beauty and mystery of the urban landscape, translating visual sensation into an almost musical experience.

The Etcher and Printmaker

Parallel to his painting career, Whistler was a prolific and innovative printmaker, particularly renowned for his etchings and lithographs. His early training in mapmaking provided a strong technical foundation, but he quickly developed a highly personal and influential style. His "French Set" (1858) and "Thames Set" (published 1871) established his reputation as a master etcher, capturing scenes with spontaneity and atmospheric effect.

Whistler experimented constantly with etching techniques, varying inks, papers, and wiping methods to achieve unique impressions. He often left large areas of the plate untouched, using selective detail and suggestive lines to evoke mood and space. His approach contrasted sharply with the highly finished, reproductive etchings common at the time. He treated each print as an original work of art, carefully controlling the printing process.

Following his bankruptcy in 1879 (a consequence of the Ruskin trial), Whistler traveled to Venice, commissioned to produce a set of twelve etchings. He stayed for over a year, ultimately creating around fifty etchings and numerous pastels. The "Venice Set" marked a further evolution in his style, characterized by shimmering light, intricate detail, and delicate atmospheric effects. Whistler's prints significantly influenced the Etching Revival in Britain and America and inspired generations of printmakers, including artists like Walter Sickert (though their relationship later soured) and Joseph Pennell, who became his biographer. He collaborated with printers like Max Philippe and worked with dealers such as Edward G. Kennedy to distribute his work.

Controversy and Character: The Ruskin Trial

Whistler's career was marked by public controversy, none more famous than his libel suit against the eminent art critic John Ruskin. In 1877, Ruskin reviewed Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, which was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. Appalled by its abstract nature and price, Ruskin wrote a scathing critique, accusing Whistler of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face."

Deeply offended and concerned about the damage to his reputation and livelihood, Whistler sued Ruskin for libel in 1878. The trial became a public spectacle, pitting Whistler's "Art for Art's Sake" philosophy against Ruskin's belief in art's social and moral responsibilities. Whistler defended his work with characteristic wit, arguing that the Nocturne was an artistic arrangement whose value lay in its harmony, not its subject matter.

Although Whistler technically won the case, the jury awarded him only a symbolic farthing (the smallest coin) in damages, indicating little sympathy for his position. The legal costs were ruinous, contributing significantly to Whistler's bankruptcy in 1879. Despite the financial disaster, the trial cemented Whistler's image as a defiant modernist and brought the fundamental questions about the nature and purpose of art into sharp public focus. The dispute with Frederick Leyland over the Peacock Room further highlighted Whistler's often difficult relationships with patrons and his uncompromising artistic vision.

Later Years and Recognition

The bankruptcy forced Whistler to sell his lavishly decorated home, the White House in Chelsea. He retreated to Venice for fourteen months, a period of intense creativity that produced the remarkable Venice etchings and pastels. Upon returning to London, he gradually rebuilt his career and reputation. He continued to paint portraits and landscapes, often working with pastel and watercolor alongside oil.

During the 1880s and 1890s, Whistler's work began to gain wider acceptance and international acclaim. He was elected President of the Society of British Artists in 1886, though his attempts to reform the institution led to conflict and his eventual resignation. He received honors from institutions in France, Germany, and Italy. In 1891, the French state purchased Whistler's Mother for the Musée du Luxembourg (it is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay), a major mark of recognition.

A highly successful retrospective exhibition of his paintings, titled Nocturnes, Marines & Chevalet Pieces, was held at the Goupil Gallery in London in 1892, consolidating his status as a major artist. He continued to travel, spending time in Paris where he maintained friendships with figures like the poet Stéphane Mallarmé and interacted with younger artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Despite periods of ill health, he remained active until shortly before his death.

Personal Life and Persona

Whistler cultivated a distinctive public persona. He was known for his dandyism—his immaculate dress, monocle, and famous white lock of hair that stood out against his dark curls. His sharp wit and penchant for public disputes were legendary, documented in his book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890), which compiled his correspondence, pamphlets, and accounts of his quarrels, including the Ruskin trial transcript.

His personal life included relationships with several women, notably his mistress and model Joanna Hiffernan (featured in the Symphony in White paintings), and his later marriage to Beatrix Whistler (née Birnie Philip), the widow of architect E. W. Godwin and an artist herself. His relationship with his mother, Anna, was complex but clearly deeply felt, immortalized in his most famous painting.

Anecdotes abound regarding his humor and sometimes prickly interactions. He famously used a stylized butterfly monogram as his signature, evolving over time, which perfectly symbolized the delicate yet sometimes stinging nature of his art and personality. Despite living a often extravagant lifestyle that frequently led to debt, his dedication to his artistic principles remained unwavering.

Legacy and Influence

James Abbott McNeill Whistler died in London on July 17, 1903, and was buried in the Old Chiswick Cemetery. His influence on the course of art was profound and multifaceted. As a central figure in the Aesthetic Movement, his advocacy for "Art for Art's Sake" fundamentally shifted discussions about the purpose and evaluation of art, paving the way for twentieth-century formalism and abstraction.

His innovative approach to color and composition, particularly in the Nocturnes and tonal portraits, influenced both American Tonalism and European Symbolism. His mastery of etching and lithography revitalized printmaking as a fine art form and inspired countless artists. His engagement with Japanese art was crucial to the development of Japonisme and demonstrated the fruitful possibilities of cross-cultural artistic dialogue, influencing figures like Auguste Rodin.

Whistler's work bridged American, British, and French art scenes. He brought a sophisticated, cosmopolitan sensibility to London and challenged the prevailing tastes of Victorian England. While sometimes overshadowed by the French Impressionists (with whom he shared some affinities but maintained distinct goals), Whistler's unique synthesis of realism, aestheticism, and Japonisme secured his place as a major innovator and a key precursor to modern art. His biographer, Joseph Pennell, emphasized his enduring connection to his homeland, despite his expatriate life.

Major Collections

Whistler's works are held in major museums and galleries worldwide. Significant collections can be found in:

United States: The Freer Gallery of Art (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., holding the largest collection, including the Peacock Room), the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), the Frick Collection (New York City), the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston), the Hill-Stead Museum (Farmington, CT), and university collections such as those at Dartmouth College and the Rhode Island School of Design.

United Kingdom: The Hunterian Art Gallery (University of Glasgow, Scotland, housing a major collection of paintings, drawings, and prints from his wife's estate), Tate Britain (London), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), and The Barber Institute of Fine Arts (University of Birmingham).

France: The Musée d’Orsay (Paris, home to Whistler's Mother) and the Musée du Louvre (Paris).

These institutions preserve the rich legacy of an artist whose work continues to captivate viewers with its subtle beauty, formal elegance, and evocative power.

Conclusion

James Abbott McNeill Whistler remains a towering figure in the art history of the late nineteenth century. An artist of exceptional technical skill and radical vision, he challenged the artistic conventions of his time, championing the autonomy of art and exploring the subtle harmonies of color and form. From his iconic portraits and atmospheric Nocturnes to his groundbreaking etchings and immersive environments like the Peacock Room, Whistler's work embodies the spirit of the Aesthetic Movement and anticipates key developments of Modernism. His complex personality, public battles, and unwavering dedication to his artistic principles make him an enduringly compelling figure, an American master who left an indelible mark on the international art world.