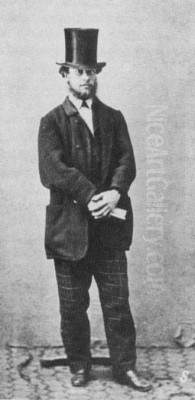

Telemaco Signorini stands as one of the most significant figures in nineteenth-century Italian art. Born in Florence in 1835 and passing away there in 1901, his life and career spanned a period of immense political and artistic change in Italy. He was not only a highly accomplished painter but also an influential writer, critic, and a central personality within the Macchiaioli group, the movement that revolutionized Italian painting by embracing realism and the study of light and colour directly from nature. His work reflects a deep engagement with the social realities of his time, a keen eye for the effects of light, and a willingness to experiment with composition and technique, leaving a lasting legacy on Italian art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Telemaco Signorini was born into an environment steeped in art. His father, Giovanni di Lorenzo Signorini, was a respected painter working for the court of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold II. This familial connection provided young Telemaco with early exposure to artistic practice and the cultural milieu of Florence. While he initially pursued literary studies, his passion for painting soon took precedence.

He enrolled briefly at the Florence Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze) but found the rigid academic training unconducive to his developing artistic sensibilities. Like many progressive artists of his generation, Signorini felt a stronger pull towards direct observation of the world around him. As early as 1854, he began experimenting with painting outdoors, en plein air, seeking to capture the authentic light and atmosphere of the Tuscan landscape. This departure from studio-bound academic practice was a crucial step in his artistic development.

A pivotal location in Signorini's formative years was the Caffè Michelangelo in Florence. This café became the regular meeting place for a group of rebellious young artists and intellectuals who gathered to discuss art, politics, and the need for a new, modern Italian art form. Here, Signorini engaged in lively debates with figures who would become his fellow Macchiaioli, including Odoardo Borrani, Vincenzo Cabianca, Cristiano Banti, and the influential critic Diego Martelli. These discussions, fueled by patriotic fervor linked to the ongoing Risorgimento (the movement for Italian unification), solidified Signorini's commitment to realism and his rejection of outdated artistic conventions.

The Macchiaioli Revolution and the Power of the 'Macchia'

Signorini emerged as a leading voice and practitioner within the Macchiaioli movement, which flourished primarily between 1855 and the late 1860s. The name "Macchiaioli," initially used derisively by a critic, derived from the Italian word "macchia," meaning "spot" or "patch." This term referred to the group's innovative technique of using distinct patches or spots of colour and contrasting tones (chiaroscuro) to construct form and represent the effects of light, rather than relying on traditional methods of precise drawing and gradual shading.

The Macchiaioli sought to break free from the historical and mythological subjects favored by the Academy. Instead, they turned their attention to contemporary life, depicting landscapes, scenes of rural labor, domestic interiors, and events related to the Risorgimento. Their commitment to painting outdoors was fundamental, allowing them to study the fleeting effects of natural light and atmosphere firsthand. Signorini, alongside key figures like Giovanni Fattori and Silvestro Lega, championed this approach.

Signorini's understanding and application of the macchia technique were sophisticated. He used bold contrasts of light and shadow not just to depict reality but also to convey mood and social commentary. His paintings from this period often feature strong compositional structures and a vibrant, direct application of paint, capturing the immediacy of observed reality. He was not merely a painter within the group; his articulate writings and critical reviews helped define and defend the Macchiaioli's artistic aims against conservative opposition.

War, Travel, and Broadening Artistic Horizons

The political turmoil of the Risorgimento directly impacted Signorini's life and art. In 1859, he volunteered to fight in the Second Italian War of Independence alongside fellow artists Odoardo Borrani and Cristiano Banti. His experiences on the battlefield provided subject matter for several significant works, where he depicted the realities of military life and conflict with unvarnished truthfulness. Paintings such as The March of the Zuavi (Bozetto la "Battaglia di Solferino"), The Expulsion of the Austrians from the Village, and The Austrians Spying from the Choir Loft of Solferino Castle reflect this period, combining his realist approach with patriotic sentiment.

Signorini's artistic perspective was further broadened by his travels. A visit to the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1855 exposed him to the works of French artists, including the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the landscapes of the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Constant Troyon. He also admired the work of Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. These encounters reinforced his commitment to realism and contemporary subjects.

He made his first significant trip to Paris in 1861 and returned frequently, also visiting London. These journeys allowed him to connect with the European avant-garde. Most notably, he formed a close and lasting friendship with the French Impressionist Edgar Degas, whom he likely met during Degas's visits to Florence in the late 1850s or early 1860s. They shared an interest in modern subjects, innovative compositions, and the influence of photography. Degas reportedly admired Signorini's work, particularly the psychologically charged The Ward of the Madwomen at S. Bonifacio in Florence. Signorini also established connections with other artists, including possibly James McNeill Whistler, although details of specific collaborations remain scarce. These international contacts kept him abreast of broader European artistic developments.

Evolving Style, Technique, and Social Commentary

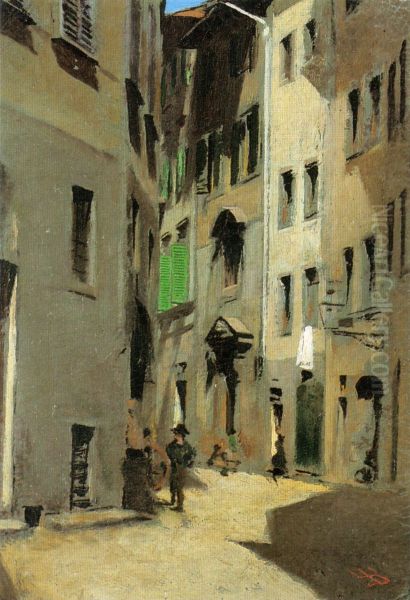

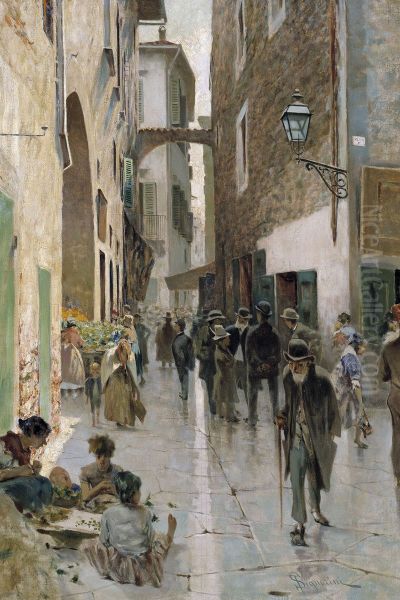

Throughout his career, Signorini's style evolved while remaining rooted in the principles of realism and the macchia. He became known for his sometimes "violent chiaroscuro," using strong contrasts to create dramatic effects and highlight specific elements within his compositions. His subject matter was diverse, ranging from sun-drenched Tuscan landscapes and intimate views of Florence's streets and alleys, like the notable Via Torta, Firenze (1870), to poignant scenes of everyday life and labor.

A significant aspect of Signorini's work is its undercurrent of social commentary. He did not shy away from depicting the harsher realities of life for the less privileged. The Towpath (L'Alzaia), for instance, portrays the grueling labor of men hauling a barge, a powerful statement on working-class hardship often overlooked in more idealized contemporary art. Similarly, Prison in Portoferraio offers a stark glimpse into the grim conditions of prison life, rendered with his characteristic strong light and shadow. His painting The Ghetto of Florence, created before the area's demolition, serves as an invaluable historical and social document.

Signorini's compositional sense became increasingly sophisticated over time. He absorbed lessons from photography, evident in the sometimes unconventional cropping and framing of his scenes, capturing seemingly spontaneous moments. Furthermore, his exposure to Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, likely encountered during his time in Paris, influenced his later work. He experimented with flattened perspectives and decorative compositional structures, as seen in works like Borgo di Porta Adriana a Ravenna, demonstrating his continuous search for new modes of visual expression. Beyond oil painting, Signorini was also a skilled printmaker, producing numerous etchings and engravings, often depicting scenes of Florence and the Tuscan countryside, such as the print Bapin del Lilela.

Later Career, Teaching, and Enduring Legacy

While the main collective force of the Macchiaioli movement diminished after the mid-1860s, Signorini remained a vital and active artist. He continued to paint, travel, and exhibit his work both in Italy and abroad, finding particular success in the British art market. His later landscapes, such as The Silent Stream (1890), show a continued mastery of light and atmosphere, perhaps with a softer palette compared to some of his earlier, more starkly contrasted works. Works like Le Bigherinaie (The Bobbin Lace Makers) demonstrate his ongoing interest in capturing scenes of local life and labor with sensitivity.

In 1892, Signorini accepted a teaching position at the Instituto Superiore di Belle Arti in Florence, passing on his knowledge and experience to a new generation of artists. He also remained an active writer and critic, contributing significantly to Italian art discourse. His writings, including the memoir Caricaturisti e Caricaturati al Caffè Michelangiolo, provide invaluable insights into the Macchiaioli circle and the artistic debates of the time.

Telemaco Signorini's influence extends beyond his immediate circle. As a key proponent of realism and plein air painting in Italy, he helped pave the way for later developments, including Italian Naturalism and artists who bridged the gap between the Macchiaioli and Impressionism, such as Giuseppe De Nittis and Federico Zandomeneghi. His commitment to depicting contemporary reality, his technical innovations with the macchia, his willingness to engage with social issues, and his role as an intellectual force within the Macchiaioli movement secure his place as a major figure in nineteenth-century European art. His works continue to be admired for their visual power, historical significance, and profound connection to the land and life of Tuscany. He died in his native Florence in 1901, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work that testifies to a life dedicated to the pursuit of artistic truth.