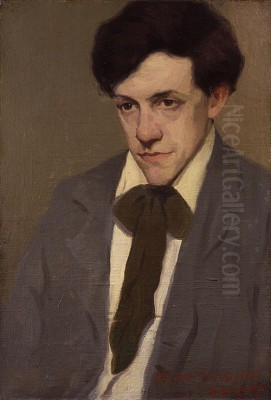

James Bolivar Manson (1879-1945) occupies a unique, albeit complex, position in the annals of early 20th-century British art. He was both a practicing artist, deeply influenced by French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and a significant figure in the London art administration, most notably serving as the Director of the Tate Gallery. His career reflects the shifting tides of artistic taste in Britain, the embrace of continental styles, and the institutional challenges of promoting modern art during a period of transition. Born in London, his life and work were predominantly centered in the British capital, yet his artistic sensibilities were profoundly shaped by experiences across the Channel.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Paddington, London, on June 26, 1879, James Bolivar Manson's path towards an artistic career was not straightforward. His father, James Alexander Manson, held literary pursuits but strongly disapproved of his son's artistic ambitions, initially pushing him towards a career in banking. Despite this familial opposition, the young Manson harboured a deep desire to paint. He pursued his passion through evening classes at Heatherley's School of Fine Art and later at Lambeth School of Art, laying the groundwork for his technical skills while working unhappily as a bank clerk.

The decisive break came around 1903 when Manson defied his father's wishes and travelled to Paris, the vibrant heart of the European art world. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a crucible for many international artists seeking to absorb the latest artistic currents. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him directly to the revolutionary works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists that were transforming visual expression. His time in France cemented his commitment to painting and set the direction for his artistic style.

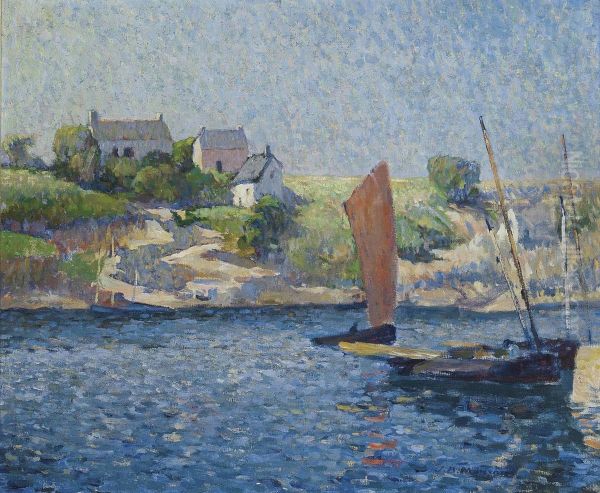

During his explorations in France, Manson discovered the picturesque fishing village of Doulan in Brittany in 1907. This location, with its rustic charm and distinct quality of light, captivated him and would become a recurring source of inspiration, not only for Manson himself but also for other British artists who followed in his footsteps, drawn to the region's authentic character and scenic beauty. This early immersion in French landscapes and artistic circles was fundamental to shaping his painterly vision.

Impressionist Influences and the Pissarro Connection

Manson's time in Paris brought him under the powerful spell of Impressionism. He deeply admired the works of masters like Claude Monet, whose dedication to capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere resonated with Manson's own burgeoning interest in landscape painting. However, perhaps the most significant personal and artistic connection he formed was with the Pissarro family. He was influenced by the patriarch, Camille Pissarro, one of the foundational figures of Impressionism.

Even more impactful was his close friendship and mentorship with Camille's son, Lucien Pissarro. Lucien had settled in London and became a vital link between French Impressionism and the British art scene. He took Manson under his wing, teaching him the principles of Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist technique. Specifically, Lucien imparted his knowledge of divisionism – the application of small, distinct dots or strokes of pure colour to create luminosity – and the use of a high-key palette, favouring bright, vibrant colours to convey the effects of natural light. This tutelage profoundly shaped Manson's brushwork and colour sense.

Manson's relationship with Lucien Pissarro extended beyond mere technical instruction; it was a deep friendship and artistic alliance. Manson became a staunch advocate for Lucien's work, writing articles about his paintings and illustrations and helping to introduce his art to potential collectors. This connection placed Manson firmly within the circle of artists seeking to establish Impressionist principles within the more conservative British art establishment.

The Camden Town Group and London's Art Scene

Upon his return to London, Manson became an active participant in the city's progressive art circles. He was initially associated with the Fitzroy Street Group, an informal collective of artists gathered around Walter Sickert, known for their realistic depictions of urban life. This group served as a precursor to the more formally constituted Camden Town Group, founded in 1911. Manson was not only a member but also served as the secretary for this influential group.

The Camden Town Group, led by the charismatic Walter Sickert, included prominent artists such as Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore, Robert Bevan, and Charles Ginner. They shared an interest in portraying scenes of everyday London life, often focusing on modest interiors, townscapes, and portraits, rendered with techniques influenced by Post-Impressionism, particularly the use of bold colour and structured compositions. While Sickert's own style often featured darker, more somber tones, artists like Gilman and Gore embraced brighter palettes, reflecting the influence of artists like Van Gogh and Gauguin. Manson's involvement placed him at the centre of this vital movement in British art.

Beyond the Camden Town Group, Manson was also involved with other artistic associations. He was a member of the London Group, formed in 1913 as an amalgamation of the Camden Town Group and other artists, creating a larger exhibiting society for modern art. Furthermore, he served as the London secretary for the Monarro Group, an association founded by Lucien Pissarro. Named in homage to Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, this group aimed to unite artists inspired by Impressionism, holding exhibitions to showcase their work and promote the Impressionist aesthetic in Britain, further demonstrating Manson's commitment to these artistic principles.

Manson's Artistic Style and Representative Works

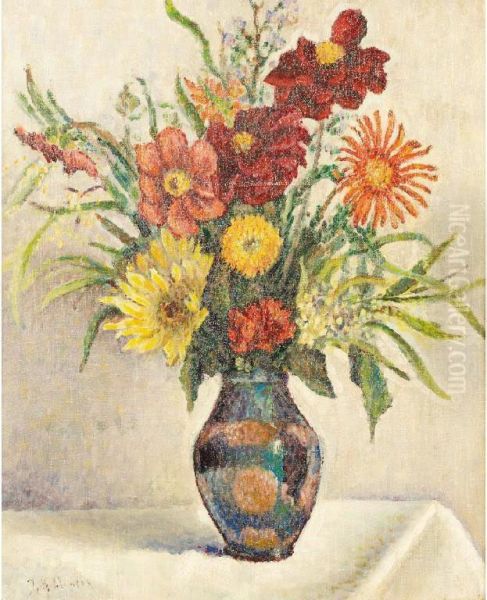

James Bolivar Manson's own artistic output primarily consisted of landscapes and still life paintings, executed in a style that evolved from Impressionism towards a Post-Impressionist sensibility. His work is characterized by a sensitivity to light and colour, often employing broken brushwork and a bright palette learned from his French exemplars and his association with Lucien Pissarro. He sought to capture the essence of a scene, whether the tranquility of the countryside or the vibrant hues of flowers.

One of his notable early works, Summer Day (c. 1907), exemplifies his Impressionist phase. Depicting a field, possibly sunflowers, under bright sunlight, it showcases his ability to capture the dazzling effects of light using vibrant yellows and greens, applied with lively brushstrokes. This work reflects the direct influence of Monet and the Impressionist focus on plein air painting and atmospheric effects.

His paintings inspired by his time in France, such as Breton Farm, capture the rustic charm of the region. These works often feature simplified forms and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow across rural architecture and landscapes, rendered with the characteristic Impressionist touch. Similarly, landscapes like McDonell demonstrate his continued engagement with natural scenery, likely depicting scenes from Britain or his travels.

Manson also excelled in still life, particularly flower painting. Works like Flowers in a Green Vase and A Study Of Flowers (c. 1910) reveal his Post-Impressionist leanings. While still attentive to light, these works often feature bolder colours, more defined forms, and a greater degree of subjective expression compared to purely Impressionist renderings. The influence of artists like Paul Cézanne might be discerned in the structural arrangement of objects, while the vibrant, sometimes non-naturalistic use of colour echoes Fauvist tendencies, filtered through his Camden Town associations. His flower paintings became particularly well-regarded.

The Tate Gallery Years: Keeper and Director

Manson's career took a significant turn towards arts administration when he joined the staff of the National Gallery, Millbank – later known as the Tate Gallery – in 1912 as a clerk. He rose through the ranks, becoming Assistant Keeper in 1917. His long association with the institution culminated in his appointment as Director in 1930, a position he held until 1938. This placed him at the helm of Britain's national collection of British art and, increasingly, modern international art.

During his tenure, particularly in the earlier years, Manson's policies were considered relatively progressive for the time, especially concerning the art he personally admired. Drawing on his own background, he was a strong supporter of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He played a role in building the Tate's collection in this area, advocating for the acquisition and display of works by artists like Monet, Degas, and his friend Lucien Pissarro. This helped solidify the presence of these crucial modern movements within the national collection.

His position allowed him to shape the public's understanding and appreciation of late 19th and early 20th-century art that aligned with his tastes. He oversaw exhibitions and collection displays, bringing the colourful palettes and innovative techniques of Impressionism to a wider British audience. His directorship occurred during a period when the Tate was defining its role and expanding its collections, making his influence potentially significant.

Challenges and Controversies at the Tate

Despite his support for Impressionism, Manson's directorship is often viewed critically and sometimes described as one of the least successful in the Tate's history. A major point of contention was his perceived conservatism towards more radical forms of modern art that emerged after Post-Impressionism. He reportedly showed reluctance, even hostility, towards acquiring or exhibiting works by leading avant-garde artists, potentially including figures associated with Cubism, Surrealism, or abstraction, such as Picasso or Matisse.

This conservative stance led to criticism that the Tate's exhibition program under his leadership became monotonous and failed to engage adequately with contemporary artistic developments. He was seen as favouring established, often older, British artists over challenging new international art, hindering the Tate's development as a truly modern museum. His personal artistic preferences seemed to limit his curatorial vision when confronted with art forms beyond the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles he championed.

Manson's tenure was further marred by personal difficulties and public controversy. He suffered from periods of depression and struggled increasingly with alcoholism. These issues led to extended absences from his post and undoubtedly affected his performance and judgment. His health problems became public knowledge, casting a shadow over his directorship.

The most infamous incident occurred in 1938 during an official dinner in Paris held in conjunction with a major British art exhibition. Manson, representing the Tate, became heavily intoxicated and caused a public embarrassment. This event, coupled with ongoing concerns about his health and management, made his position untenable. Another significant controversy arose concerning a sculpture by Constantin Brancusi, a pioneer of modern sculpture. When a Brancusi piece was held by customs, Manson allegedly sided with the view that it did not qualify as a work of art, further damaging his reputation among supporters of modernism.

Resignation, Later Life, and Legacy

The culmination of these professional controversies and personal health struggles led to James Bolivar Manson's resignation from the directorship of the Tate Gallery in 1938, officially citing health reasons. His departure marked the end of a significant, yet troubled, chapter in the museum's history and the conclusion of his public career in arts administration.

In the years following his resignation, Manson's health continued to decline, exacerbated by his ongoing battle with alcoholism. The promise of his earlier artistic career and the potential of his administrative role seemed overshadowed by these personal challenges and the controversies of his later Tate years. He continued to paint, but his output and visibility diminished. James Bolivar Manson passed away in London on July 3, 1945.

His legacy remains complex. As an artist, he was a talented painter working within the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist traditions, contributing significantly to the assimilation of these styles into British art through his own work and his activities within groups like the Camden Town Group and the Monarro Group. His paintings, particularly his landscapes and flower studies, are appreciated for their vibrant colour and sensitive handling of light. He stands alongside figures like Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert as part of the generation that bridged British art with continental modernism.

As an administrator, his record is more ambiguous. While he championed the art he understood and loved, particularly Impressionism, his resistance to later, more challenging forms of modernism and his personal difficulties ultimately hampered his effectiveness as Director of the Tate. He represents a figure caught between tradition and modernity, whose personal artistic convictions sometimes clashed with the broader responsibilities of leading a national museum in an era of rapid artistic change. His contemporaries included artists pushing boundaries further, such as Wyndham Lewis of the Vorticist movement or the celebrated portraitist Augustus John, highlighting the diverse landscape of British art against which Manson's career unfolded.

Conclusion

James Bolivar Manson's life encapsulates the journey of a British artist deeply engaged with French modernism at the turn of the 20th century. His paintings reflect a genuine talent for capturing light and colour in the Impressionist vein, while his administrative career at the Tate Gallery highlights the complexities of institutionalizing modern art. Influenced by Monet and mentored by Lucien Pissarro, he played an active role in London's progressive art circles, notably the Camden Town Group. Though his directorship of the Tate was marked by controversy and personal struggle, Manson remains a noteworthy figure whose career offers insight into the reception and development of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in Britain, and the challenges faced by artists and administrators navigating the evolving landscape of modern art.