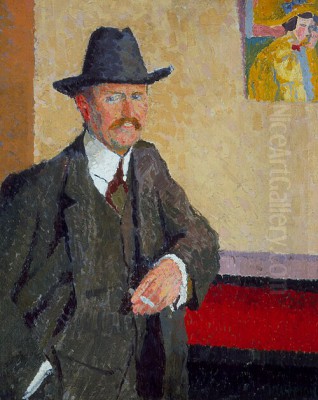

Charles Isaac Ginner stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of early twentieth-century British art. Born in Cannes, France, on March 4, 1878, to British parents, Isaac Benjamin Ginner, a medical doctor, and Adeline Wightman, Ginner's artistic journey would see him traverse geographical and stylistic boundaries, ultimately carving out a unique niche that blended Post-Impressionist sensibilities with a distinctly English form of Realism. His meticulous technique, vibrant palette, and unwavering dedication to depicting the tangible world around him, whether the bustling streets of London or the quietude of the countryside, mark him as an artist of profound integrity and singular vision.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Ginner's upbringing in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the French Riviera provided an early, albeit perhaps subliminal, exposure to a world of light and colour. His family, though British, was part of an international community, and this early environment may have fostered a broader perspective than might have been typical for a young man destined for the British art scene. Despite his father's profession in medicine, and the initial expectation that he might follow a more conventional path, Ginner harboured artistic aspirations from a young age.

The decision to pursue art professionally was not without its challenges. Family opposition, a common hurdle for many aspiring artists of the period, meant that Ginner had to assert his intentions with conviction. He initially pursued architectural studies in Paris from 1899 to 1901, a discipline that likely honed his eye for structure, form, and detailed observation – qualities that would become hallmarks of his later painting style. This architectural grounding provided a solid foundation for his subsequent explorations in paint, instilling a sense of order and precision that would temper the expressive freedom he later absorbed from Post-Impressionist masters.

Parisian Foundations: Education and Influences

The true commencement of Ginner's formal art education began in 1904 when he enrolled at the Académie Vitti in Paris. The French capital was, at this time, the undisputed epicentre of the art world, a crucible of avant-garde ideas and revolutionary artistic movements. At Académie Vitti, he studied under Henri Martin, whose own work, while rooted in Symbolism, showed an interest in light and divisionist techniques. However, Ginner also encountered the teachings of Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa, a Catalan painter known for his vibrant colours and decorative style, which may have offered an early glimpse into the expressive potential of non-naturalistic palettes.

Ginner's time at Académie Vitti was formative, but he also briefly attended the more traditional École des Beaux-Arts in 1905, studying under Gabriel Ferrier. A significant anecdote from this period highlights Ginner's burgeoning independent spirit and his alignment with more radical artistic currents: he reportedly clashed with a tutor, Paul Gervais, over his admiration for Vincent van Gogh, whose work was still considered controversial by many academic traditionalists. This incident underscores Ginner's early and passionate engagement with Post-Impressionism.

The profound impact of artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne on Ginner's developing aesthetic cannot be overstated. From Van Gogh, he absorbed the expressive power of colour and the tactile quality of impasto, the idea that paint itself could convey emotion. Gauguin's bold, flat areas of colour and his departure from purely representational hues offered a path towards greater artistic freedom. Cézanne, the "father of modern art," provided a model for structural integrity, demonstrating how a painting could be built up through carefully considered planes of colour, revealing the underlying geometry of form. Ginner also showed an appreciation for the pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat, which informed his own methodical application of paint.

In 1908, after a period of independent work, Ginner held his first solo exhibition at the Galerie B. Weill in Paris. This was a significant step, marking his emergence as a professional artist ready to present his vision to the public. His experiences in Paris, surrounded by the ferment of modern art, equipped him with a sophisticated understanding of contemporary artistic debates and techniques.

The Move to London and the Genesis of a Style

In 1909, Ginner made a pivotal decision to visit Buenos Aires, Argentina, for a year. While details of his activities there are somewhat scarce, the experience of a new continent and culture likely broadened his horizons further. However, it was his move to London in 1910 that would prove most decisive for his career. He initially took a room in Battersea, immersing himself in the urban fabric of the British capital.

London at this time was experiencing its own artistic awakenings, partly fueled by Roger Fry's groundbreaking exhibitions, "Manet and the Post-Impressionists" (1910) and the "Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition" (1912), which introduced British audiences (and many artists) to the radical developments that had been taking place on the continent. Ginner, already steeped in these influences from his Paris years, found himself well-positioned within a burgeoning modernist scene in Britain.

He quickly connected with a circle of like-minded artists, notably Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore, who were similarly grappling with how to adapt Post-Impressionist principles to a British context. Walter Sickert, an older and more established figure who had himself been an associate of Edgar Degas and a bridge between French Impressionism and British art, also became a key associate. These artists were drawn to depicting the everyday life of the city, its streets, interiors, and inhabitants, moving away from the grand historical or mythological subjects favoured by the Royal Academy.

The Camden Town Group: A Collective Vision

This shared interest in urban realism and modern French painting led directly to the formation of the Camden Town Group in 1911. Ginner was a founding member of this influential but short-lived collective. The group, which took its name from the down-at-heel North London district where Sickert and others lived and worked, aimed to organize exhibitions independent of the established art institutions.

Besides Ginner, Gilman, Gore, and Sickert, key members included Robert Bevan, Lucien Pissarro (son of the Impressionist Camille Pissarro), Malcolm Drummond, and J.B. Manson. While their individual styles varied, they were united by a commitment to subjects drawn from contemporary urban life and an engagement with the bright colours and formal innovations of Post-Impressionism. They often depicted modest domestic interiors, music halls, street scenes, and the ordinary people of London, finding beauty and significance in the mundane.

The Camden Town Group held only three exhibitions, in June and December 1911 and December 1912, at the Carfax Gallery in London. These exhibitions were crucial in promoting a distinctly British form of Post-Impressionism. The group's focus on everyday subject matter, often rendered with a degree of gritty realism, distinguished them from the more decorative or abstract tendencies of some continental modernists.

Ginner's Role in Camden Town

Within the Camden Town Group, Ginner was noted for his meticulous technique and the intensity of his observation. His paintings from this period, such as the iconic Piccadilly Circus (1912, Tate), exemplify his approach. This work captures the energy and dynamism of the famous London landmark, not through blurred Impressionistic effects, but through a carefully constructed mosaic of distinct, unblended strokes of vibrant colour. The architecture, vehicles, and figures are rendered with a solidity and precision that reflects his early architectural training and his admiration for Cézanne's structural approach.

His urban landscapes were not fleeting impressions but carefully composed and densely worked paintings. He would often make detailed preparatory drawings on site, squared up for transfer to canvas, and then build up the paint surface in the studio with small, regular touches of thick paint, creating a richly textured, almost tapestry-like effect. This methodical application, sometimes referred to as a form of "neo-realist pointillism," gave his works a unique visual character. He was less interested in the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere than in the enduring structure and character of his subjects.

Other works from this period, such as The Café Royal (1911, Tate), demonstrate his ability to capture the specific ambiance of London social life, while paintings of more prosaic subjects like Victoria Embankment Gardens (c. 1912) reveal his commitment to finding artistic value in the everyday.

Neo-Realism: A Manifesto for Modern Art

The Camden Town Group eventually dissolved, partly due to internal disagreements and the desire for a larger, more inclusive exhibiting society. It was succeeded by the London Group in 1913, of which Ginner also became a member. However, before this transition, Ginner, in collaboration with Harold Gilman, articulated a more defined artistic creed.

In January 1914, Ginner and Gilman held a joint exhibition at the Goupil Gallery. For this occasion, Ginner wrote the catalogue foreword, which served as a manifesto for what they termed "Neo-Realism." This text, published in The New Age on January 1st, 1914, under the title "Neo-Realism," was a significant statement of their artistic principles. It called for a return to the "plastic nature of things," emphasizing detailed observation, strong design, and the emotional significance of the subject matter.

The manifesto argued against the "decorative" tendencies they perceived in some Post-Impressionist art and the superficiality of academic painting. Instead, Ginner advocated for an art rooted in "intimate and intensive observation of Nature." He wrote, "The Neo-Realist... should go to Nature for his inspiration and subject-matter. His work should be a definite statement of a thing seen... Personal vision and its application to the thing seen, these should be the qualities of a work of art." This emphasis on meticulous representation, combined with a modern sensibility regarding colour and composition, defined Ginner's mature style. He and Gilman sought an art that was both modern and deeply connected to the observable world, a "New Realism" for the twentieth century.

The Impact of War: Ginner as an Official Artist

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 profoundly impacted the art world and the lives of artists. Ginner, despite his French birth, was a British subject. In 1916, he enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps, later serving with the Intelligence Corps (NZEF) from 1917 to 1918. His most significant contribution as a war artist, however, came through his work for the Canadian War Records. In 1918, he was commissioned to paint a large picture of a munitions factory, The Filling Factory, Hereford (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).

This monumental work is a testament to Ginner's painstaking method. He spent considerable time at the factory, making detailed studies of the machinery and the workers. The final painting is a complex, almost overwhelming depiction of industrial activity, rendered with his characteristic precision and dense application of paint. It captures the scale and intensity of the war effort on the home front, transforming a scene of labour into a powerful visual statement. His ability to organize complex visual information into a coherent and compelling composition is fully evident here.

During the Second World War, Ginner again served as an official war artist, this time for the British War Artists' Advisory Committee, under Sir Kenneth Clark. He was commissioned to depict various subjects, including bombed buildings and port scenes, documenting the impact of the conflict on Britain. Works like Plymouth Pier: The Great Western Railway Lost Property Office after a Blitz (1942) show his continued commitment to detailed observation, even amidst scenes of destruction. These war paintings are important historical documents as well as compelling works of art, imbued with a sense of stoicism and resilience.

Post-War Years and Continued Development

After the First World War, Ginner continued to develop his distinctive style, applying it to a wide range of subjects. He remained an active member of the London Group and also exhibited with the New English Art Club. While London remained a primary source of inspiration, he also painted extensively in the English countryside, particularly in areas like Berkshire, Essex, and Cornwall.

His rural landscapes, such as A Berkshire Landscape (c. 1920s) or Hartland Point from Boscastle (1936, Tate), possess the same meticulous detail and vibrant colour as his urban scenes. He approached nature with the same intensity of observation, carefully delineating trees, fields, and coastlines. These works are not idyllic or romanticized visions of the countryside but are grounded in a deep appreciation for the specific character of the English landscape. He often focused on the interplay of man-made structures within the natural environment, such as farms, bridges, or village streets.

Ginner's technique remained remarkably consistent throughout his career. He favoured a thick impasto, applying paint in small, distinct touches that build up to create a rich, textured surface. His colours, while often bright and non-naturalistic in a Post-Impressionist vein, were always carefully chosen to convey the essential reality and emotional resonance of the scene. He was a slow and methodical worker, producing a relatively small but consistently high-quality body of work.

Key Themes and Subjects in Ginner's Oeuvre

Ginner's body of work is characterized by a consistent focus on the tangible world. Urban landscapes, particularly of London, form a significant part of his output. He was fascinated by the city's architecture, its bustling streets, its parks, and its public spaces. Works like Flask Walk, Hampstead, on a Whit Monday (1937) or Clapham Common (1926) demonstrate his enduring interest in capturing the life of the city and its suburbs. He had a particular fondness for the red brick of London buildings, which often features prominently in his compositions, rendered with a loving attention to detail.

Rural landscapes provided a contrasting, though equally important, theme. He was drawn to the structure of the land, the patterns of fields, the forms of trees, and the character of rural architecture. His landscapes are never empty; they often include evidence of human activity, suggesting a deep connection between people and their environment.

Architectural detail was a constant preoccupation, undoubtedly stemming from his early training. Whether depicting a grand public building, a humble terraced house, or a farm outbuilding, Ginner rendered structures with a sense of solidity and precision. He was interested in the way light fell on surfaces, revealing their texture and form, but always within a framework of strong design.

The Distinctive Technique: Brushwork and Colour

Ginner's technique is one of his most defining characteristics. He typically worked on a white ground, which helped to preserve the luminosity of his colours. His application of paint was deliberate and controlled, using small brushes to lay down distinct, unblended strokes of thick paint. This method, sometimes likened to mosaic or petit point embroidery, creates a highly textured surface where each touch of the brush remains visible, contributing to the overall vibrancy and structure of the image.

This technique was laborious and time-consuming. It required intense concentration and a clear vision of the final composition from the outset. Unlike the Impressionists, who sought to capture fleeting moments, Ginner aimed for a more permanent and structured representation of reality. His paintings have a sense of density and weight, a feeling that every element has been carefully considered and placed.

His use of colour was bold and often non-naturalistic, reflecting his Post-Impressionist influences. He was not afraid to use strong contrasts and unexpected juxtapositions of hue to heighten the emotional impact of a scene or to emphasize its formal qualities. However, his colour choices were never arbitrary; they were always subservient to his overall aim of conveying the essential character of his subject. The combination of meticulous, almost obsessive detail with vibrant, expressive colour gives his work its unique power.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Beyond those already mentioned, several other works highlight Ginner's artistic achievements. The Fruit Stall, Covent Garden (1914) is a vibrant depiction of market life, teeming with detail and colour. Robertsbridge Mill (1936) showcases his ability to capture the picturesque qualities of rural industry. His numerous paintings of Hampstead, where he lived for a time, such as Pine Trees, Hampstead Heath (1925), reveal his affection for his local surroundings.

His wartime commissions, particularly The Filling Factory, Hereford, stand as major achievements, demonstrating his ability to handle complex, large-scale compositions with his characteristic precision. Even his smaller studies and watercolours, often made as preparatory works, possess a remarkable intensity and attention to detail. Each work, regardless of scale or subject, reflects his unwavering commitment to his Neo-Realist principles.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Ginner's career was interwoven with those of many leading figures in British art. His close association with Harold Gilman was particularly significant, culminating in their "Neo-Realism" manifesto. With Spencer Gore, he shared a passion for depicting everyday London life. Walter Sickert, an elder statesman of the group, provided both inspiration and a degree of mentorship, though Ginner's style ultimately diverged from Sickert's more tonal and atmospheric approach.

He was part of a generation that included artists like Robert Bevan, known for his paintings of horses and London street scenes, and Lucien Pissarro, who brought a direct link to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. While associated with the London Group, he would have encountered a diverse range of artists, including figures like Wyndham Lewis, the driving force behind Vorticism, though Ginner's own art remained firmly rooted in representation.

His contemporaries also included artists like Augustus John, a more flamboyant figure in British art, and later, war artists such as Paul Nash and C.R.W. Nevinson, who were also tasked with documenting the conflicts of the twentieth century, albeit often with different stylistic approaches. Ginner's steadfast adherence to his own vision, amidst the rapidly changing currents of modern art, is a testament to his artistic integrity. He was respected by his peers for his dedication and the distinctive quality of his work.

Later Life and Recognition

Ginner continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He taught at Westminster School of Art from 1919 until 1927, alongside Harold Gilman (until Gilman's early death in 1919) and later Walter Bayes, influencing a new generation of students. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1942, a belated but significant recognition from the art establishment. This was followed by his election as a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1950.

His contribution to British art was further acknowledged when he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1950. Despite suffering from crippling arthritis in his later years, which made his meticulous painting process increasingly difficult, he continued to work with unwavering determination. Charles Ginner passed away in London on January 6, 1952, leaving behind a body of work that stands as a unique and compelling record of his time.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Charles Ginner's legacy is that of an artist who forged a highly personal style from the currents of European modernism and a deep-seated commitment to the observable world. He was a key figure in the Camden Town Group and, with Gilman, a proponent of Neo-Realism, offering a distinct British response to Post-Impressionism. His emphasis on detailed observation, strong design, and the emotional significance of everyday subjects provided an alternative to both academic conservatism and more radical forms of abstraction.

While perhaps not as widely known as some of his contemporaries, Ginner's work is held in high regard by those familiar with British art of the period. His paintings are prized for their integrity, their technical skill, and their unique visual intensity. They offer a fascinating window onto the urban and rural landscapes of early to mid-twentieth-century Britain, rendered with a passion and precision that remains compelling. His influence can be seen in later British artists who have similarly sought to combine meticulous realism with a modern sensibility.

His works are represented in major public collections, including Tate Britain, the Ashmolean Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and the National Gallery of Canada, ensuring that his distinctive vision continues to be appreciated by new audiences.

Conclusion

Charles Ginner was an artist of quiet conviction and remarkable consistency. From his early immersion in the artistic ferment of Paris to his mature career as a leading figure in British modernism, he remained true to his vision of an art rooted in the careful observation of reality, yet enlivened by the expressive potential of colour and form. His meticulous, jewel-like paintings of city streets, rural landscapes, and wartime Britain offer a rich and enduring testament to his unique talent. As a chronicler of his time, and as an artist who successfully synthesized continental modernism with a deeply personal and English sensibility, Charles Ginner holds a secure and important place in the history of British art.