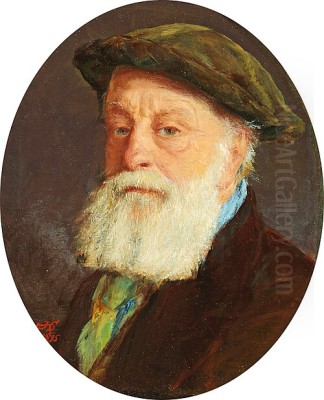

James Clarke Hook (1819-1907) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British Victorian art. A painter and etcher of considerable skill and consistent output, Hook carved a distinct niche for himself with his evocative marine paintings, rustic genre scenes, and historical subjects. His work, characterized by a robust naturalism blended with a romantic sensibility, captured the imaginations of his contemporaries and continues to hold appeal for its honest depiction of coastal life and the enduring power of nature. This exploration delves into the life, career, artistic style, and legacy of this distinguished Royal Academician.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in London on November 21, 1819, James Clarke Hook's familial background was intellectually vibrant. His father, also named James Hook, served as a judge in the mixed commission courts in Sierra Leone, a position of some standing. His mother was the daughter of the esteemed Wesleyan theologian and Bible commentator, Dr. Adam Clarke. This connection to a scholarly and devout family likely instilled in young Hook a disciplined approach to his endeavors.

While his father's profession involved periods in West Africa, Hook's early education took place in England, reportedly at a private school in Eton. His artistic talents emerged early, and he was fortunate to receive encouragement. An important early influence and guide was the landscape master John Constable, whose emphasis on direct observation of nature and the atmospheric effects of light and weather would resonate throughout Hook's career, even as his subject matter evolved.

The formal art education for aspiring artists in Britain at the time was centered around the Royal Academy Schools in London. Hook gained admission in 1836, embarking on a rigorous course of study that involved drawing from casts of classical sculptures and, eventually, from life models. This academic training provided a strong foundation in draughtsmanship and composition, essential skills for any nineteenth-century painter.

The Royal Academy and Formative Years

Hook's progress at the Royal Academy Schools was marked by notable success. In 1842, he distinguished himself by winning the first gold medals for both drawing from life and for historical painting, a testament to his burgeoning talent and dedication. His early works often tackled historical and literary themes, popular subjects in the academic tradition.

A pivotal moment came in 1845 when his historical painting, The Finding of the Body of Harold at the Battle of Hastings, earned him the prestigious gold medal and, crucially, a three-year traveling scholarship from the Royal Academy. This scholarship was a coveted prize, enabling promising young artists to study the great masterpieces of European art, particularly in Italy, firsthand. Such an experience was considered essential for rounding out an artist's education and refining their taste.

Before embarking on his continental travels, Hook married Rosalie Burton in 1846. His wife was also an artist, and their shared passion for art would be a constant throughout their lives. The journey to Italy, a rite of passage for many British artists from J.M.W. Turner to Lord Leighton, was to have a profound impact on Hook's artistic development, particularly his understanding and use of color.

Italian Sojourn and the Influence of the Masters

The years spent in Italy, from roughly 1846 to 1849, were transformative for James Clarke Hook. He immersed himself in the study of the Italian Old Masters, with the Venetian School, in particular, leaving an indelible mark on his style. The rich, luminous colors and expressive brushwork of painters like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto deeply impressed him. He spent time copying their works, a traditional method of learning, and absorbing their techniques for rendering light, texture, and human emotion.

While in Paris, likely en route to or from Italy, Hook also spent time studying at the Louvre. The exposure to a wide range of European art, from the Italian Renaissance to contemporary French painting, broadened his artistic horizons. He was particularly drawn to the Venetians' ability to combine dramatic storytelling with a sensuous appreciation for color and surface. This influence would manifest in his later works, not in direct imitation, but in a heightened sense of color harmony and a more painterly application of pigment.

Though his early successes were in historical painting, the Italian experience, combined with his inherent love for nature, began to steer him towards subjects that allowed for a more personal and direct engagement with the world around him. The vibrant light and picturesque scenery of Italy, along with its everyday life, provided ample inspiration.

Development of a Distinctive Style: The Call of the Sea

Upon his return to England, Hook continued to exhibit historical and literary subjects for a time. However, by the mid-1850s, a significant shift occurred in his thematic focus. Around 1854, he began to concentrate on the subjects that would define his mature career: scenes of coastal life, fishermen at their toil, and the dramatic interplay of sea and shore. This change marked the true establishment of his individual artistic voice.

His new direction was met with critical and popular acclaim. Works depicting the rugged coastlines of Devon, Cornwall, and later, the fishing villages of Brittany and Holland, became his hallmark. These were not merely picturesque views; Hook's paintings delved into the daily lives, struggles, and simple pleasures of the people who made their living from the sea. He brought a sense of authenticity and empathy to these subjects, born from careful observation and a genuine appreciation for their way of life.

His style evolved to suit these new themes. While retaining the strong drawing and compositional skills honed in his academic training, his brushwork became freer and more expressive, his palette richer and more attuned to the nuanced colors of the coast – the deep blues and greens of the water, the earthy tones of the cliffs, and the pearlescent light of the sky. He masterfully captured the textures of wet sand, weathered boats, and coarse fishing nets. This approach combined elements of Realism, in its truthful depiction of subject matter, with a Romantic sensibility, evident in the often dramatic or emotionally resonant portrayal of his scenes. He shared this affinity for the British coastline with contemporaries like William Collins and, in a more dramatic vein, Clarkson Stanfield.

Key Themes and Subjects in Hook's Art

The sea, in all its moods, was Hook's most enduring muse. He painted it calm and inviting, and wild and treacherous. His canvases are populated with hardy fishermen and their families, engaged in their daily routines: mending nets, launching boats, hauling in their catch, or anxiously awaiting the return of loved ones from a stormy sea.

Titles such as Luff, Boy! (1859), a Royal Academy sensation, The Mussel Gatherers (1860), and Leaving at Low Water, Scilly Isles (1861) exemplify his focus. These works are characterized by their narrative clarity and emotional depth. He often depicted moments of quiet heroism, resilience, and communal spirit. Children feature prominently, sometimes playing on the shore, sometimes assisting with tasks, their presence adding a touch of innocence and poignancy to the scenes.

Hook's approach was distinct from the sublime, often overwhelming, seascapes of J.M.W. Turner. While Hook could certainly convey the power of the ocean, his primary interest lay in the human relationship with it. His figures are not dwarfed by nature but are an integral part of it, their lives shaped by its rhythms and demands. This human-centered approach to marine painting set him apart and resonated with a Victorian audience that appreciated narrative and sentiment. His detailed observation of rural and coastal life also found parallels in the work of genre painters like Thomas Faed, who depicted Scottish peasant life with similar empathy.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

Throughout his long career, James Clarke Hook produced a remarkable body of work, consistently high in quality. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his achievements.

_Caught by the Tide_ (1869): This painting depicts a poignant scene of a young woman and child stranded on a rapidly diminishing patch of land as the tide rushes in. The sense of peril and the emotional bond between the figures are powerfully conveyed, set against a beautifully rendered coastal backdrop.

_Deep Sea Fishing_ (1864): Exhibiting his skill in portraying the robust activity of fishermen at sea, this work captures the energy and danger of their profession. The dynamic composition and the realistic depiction of the figures and their equipment are characteristic of Hook's best marine pieces.

_Catching a Mermaid_ (1883): This title suggests a more whimsical or fantastical element, which Hook occasionally incorporated into his work, blending realism with a touch of folklore or romantic imagination. Such works demonstrate his versatility and his ability to infuse everyday scenes with a sense of wonder.

_Cow Tending_ (1874) (also known as _The Bonxie, Shetland_): While renowned for his marine subjects, Hook also painted pastoral scenes. This work, depicting a figure tending cattle in a rugged landscape, showcases his ability to capture the character of different environments and the lives of those who inhabit them. The atmospheric quality and the sensitive portrayal of the animals and human figure are notable.

_The Wily Angler_ (1876): This painting, showing a young boy intently fishing, is a charming example of Hook's ability to capture moments of quiet concentration and the simple pleasures of rural life. The detailed rendering of the natural setting and the figure's absorption in his task are typical of Hook's engaging genre scenes.

His works were regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy, where he was elected an Associate (ARA) in 1850 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1860. This recognition solidified his position as one of the leading painters of his generation. His paintings were sought after by collectors and were often reproduced as engravings, further widening their popularity.

Hook and His Contemporaries

James Clarke Hook operated within a vibrant and diverse Victorian art world. While he developed a distinctive personal style, his work can be seen in relation to several broader artistic currents and individual contemporaries.

His commitment to "truth to nature," particularly in his detailed rendering of coastal environments and human activity, aligned with the principles championed by the influential critic John Ruskin. Although Hook was not formally associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), whose members like John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti also emphasized meticulous detail and direct observation, his work shared some of their earnestness and rejection of overly idealized academic conventions. However, Hook's style was generally broader and more painterly than the hard-edged precision of early Pre-Raphaelitism.

In the realm of marine painting, he followed in the tradition of earlier British artists but brought a new focus on the human element. While Clarkson Stanfield and Edward William Cooke were also prominent marine painters of the era, Hook's emphasis on narrative and the daily lives of fisherfolk gave his work a unique appeal. He was less concerned with grand naval battles or purely topographical views and more interested in the intimate relationship between people and the sea.

His genre scenes, depicting rural and coastal life, can be compared to the work of Scottish artists like Thomas Faed or English painters like Frederick Walker, who also found inspiration in the lives of ordinary working people. However, Hook's particular focus on the maritime setting remained his most defining characteristic.

He was known to have professional interactions with fellow artists. For instance, he reportedly invited the artist Alexander Macdonald to paint portraits of artists and collect their sketches, fostering a sense of community. His marriage to Rosalie Burton, an artist herself, also placed him within a network of creative individuals.

The Printmaker: Hook's Etchings

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, James Clarke Hook was also an accomplished etcher. He embraced this medium as another avenue for artistic expression, often translating the themes and compositions of his paintings into prints. Etching allowed for a different quality of line and tone, and Hook explored its potential with skill.

His etchings, like his paintings, frequently depicted coastal scenes, fishermen, and boats. The directness and spontaneity often associated with etching suited his observational approach. These prints helped to disseminate his images to a wider audience and contributed to his reputation. His involvement with printmaking aligns him with other Victorian painter-etchers such as James McNeill Whistler (though Whistler's style was markedly different) and Sir Francis Seymour Haden, who were instrumental in the Etching Revival in Britain. This revival sought to elevate etching as an original art form, rather than merely a reproductive one.

Later Career and Recognition

James Clarke Hook enjoyed a long and consistently successful career. He continued to paint and exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy and other institutions well into his old age. His home and studio at Silverbeck, Churt, Surrey, became a hub of creativity. He was a respected figure in the art establishment, and his works remained popular with the public.

His paintings were not only exhibited in Britain but also found their way into international exhibitions, including Paris and Luxembourg, indicating his broader European reputation. The consistency of his vision and the high quality of his execution ensured that his work remained in demand. He was a dedicated family man, and his sons, Allan James Hook and Bryan Hook, also became artists, following in their father's footsteps.

He remained active as a painter almost until his death. James Clarke Hook passed away on April 14, 1907, at his home in Churt, Surrey, at the venerable age of 87. He left behind a significant body of work that provides a rich and insightful portrayal of Victorian coastal life.

The Berners Street Hoax: A Curious Anecdote

An intriguing, if somewhat debated, anecdote associated with James Clarke Hook by some sources (though more famously and verifiably attributed to Theodore Hook, a different individual, in 1810) is his purported involvement in a version of the "Berners Street Hoax." According to the information provided for this article, James Clarke Hook was said to have orchestrated a large-scale prank. This involved sending out thousands of letters to various tradespeople, professionals, and dignitaries, requesting their services or presence at a specific address – that of a Mrs. Tottenham on Berners Street – all on the same day.

The alleged list of invitees was extensive and eclectic, supposedly including piano movers, eye doctors, barbers, bakers, clergy, and even a six-person organ band and prominent figures like the Lord Mayor of London and the Duke of York. The result, as described, was utter chaos, with a massive convergence of people and services upon the unfortunate Mrs. Tottenham's residence, leading to gridlock and public spectacle. The story suggests that Hook's role as the instigator was only revealed after the commotion had subsided. If indeed connected to James Clarke Hook the painter, this event would stand in stark contrast to his otherwise serious artistic persona, revealing a mischievous and audacious side. However, it is crucial to note the strong historical attribution of the original, famous Berners Street Hoax of 1810 to Theodore Hook, a writer and humorist, when James Clarke Hook would have been non-existent or an infant. The user's source material specifically links this type of event to James Clarke Hook the painter, and it is presented here as per that source.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

James Clarke Hook's legacy rests on his authentic and evocative depictions of the British coast and its people. He was a master of narrative genre painting within a maritime context, capturing both the beauty and the harsh realities of life by the sea. His work offers a valuable window into the social and cultural landscape of Victorian Britain.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, like the Pre-Raphaelites or later Impressionist-influenced painters such as Philip Wilson Steer, Hook's contribution was significant. He brought a new level of realism and empathy to marine painting, moving beyond purely picturesque or grandly historical representations. His influence can be seen in later generations of British coastal painters who continued to explore similar themes.

His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, and various regional galleries throughout the United Kingdom. They continue to be appreciated for their technical skill, their narrative interest, and their heartfelt portrayal of a way of life intrinsically linked to the sea. Artists like Stanhope Forbes and the Newlyn School painters, who also focused on realistic depictions of fishing communities in Cornwall in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, can be seen as inheritors of the tradition that Hook helped to popularize.

Conclusion

James Clarke Hook RA was a distinguished and highly regarded artist of the Victorian era. From his early successes in historical painting to his mature focus on marine and coastal genre scenes, he demonstrated a consistent commitment to quality and a deep understanding of his subjects. Influenced by masters like Constable and Titian, he forged a unique style that blended academic rigor with a romantic sensibility and a realist's eye for detail. His depictions of the lives of fisherfolk, the dramatic beauty of the British coastline, and the ever-present power of the sea have secured him an enduring place in the annals of British art. His work remains a testament to the enduring human connection with the maritime world and the timeless appeal of skillfully rendered, emotionally resonant art.