James Sharples (1751-1811) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of late 18th and early 19th-century portraiture. An English artist who found considerable success in the nascent United States, Sharples specialized in pastel portraits, a medium that allowed for both speed of execution and a delicate, lifelike quality. His legacy is intrinsically linked to his depictions of key figures of the American Revolution and the early Federal period, providing us with intimate glimpses of the men and women who shaped a new nation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in England

Born in Wakefield, Lancashire, England, around 1751 or 1752, James Sharples' early life pointed towards a future in the clergy. However, the allure of art proved stronger, and he eventually redirected his ambitions towards a career as a painter. While details of his earliest artistic training can be somewhat elusive, it is widely accepted that he received instruction from the prominent English portraitist George Romney.

Studying under an artist of Romney's caliber would have provided Sharples with a solid foundation in the prevailing neoclassical and romantic portrait styles popular in Britain. Romney, a contemporary and rival of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, was celebrated for his elegant and often psychologically insightful portraits. This environment would have exposed Sharples to high standards of draftsmanship, composition, and the nuanced rendering of likeness and character. His time in England saw him working in various cities, including Liverpool, Bath, and Bristol, honing his skills before his pivotal decision to venture across the Atlantic.

Sharples developed a particular proficiency in pastels, a medium favored for its soft, velvety texture and the immediacy with which an artist could capture a sitter's features. He often worked on a thick, grey, textured paper, which provided a sympathetic ground for the vibrant pigments. While he also produced oil paintings, it was his pastel work that would define his career, particularly in America.

The American Venture: A New Canvas

In 1793, accompanied by his third wife, Ellen Wallace Sharples (herself a talented artist), and their children, James Sharples embarked for the United States. This was a period of great flux and opportunity in the newly independent nation. There was a burgeoning demand for portraits, as political leaders, military heroes, and affluent citizens sought to commemorate their roles and status in the young republic.

The Sharples family initially landed in New York. James quickly established a reputation for his skillful and relatively affordable pastel portraits. His practice was somewhat itinerant, as he traveled to various cities where prominent individuals congregated, most notably Philadelphia, which was then the nation's capital. It was here that he would create some of his most enduring images.

His method was efficient and well-suited to a clientele that might not have had the time or inclination for lengthy sittings required for large-scale oil portraits. Sharples often employed a physiognotrace, a mechanical drawing aid that helped to quickly and accurately capture the profile of a sitter. This device, popularized by French artists like Gilles-Louis Chrétien, allowed for the creation of a precise outline, which the artist would then fill in with pastels, adding color, shading, and individual characteristics.

Signature Style and Working Method

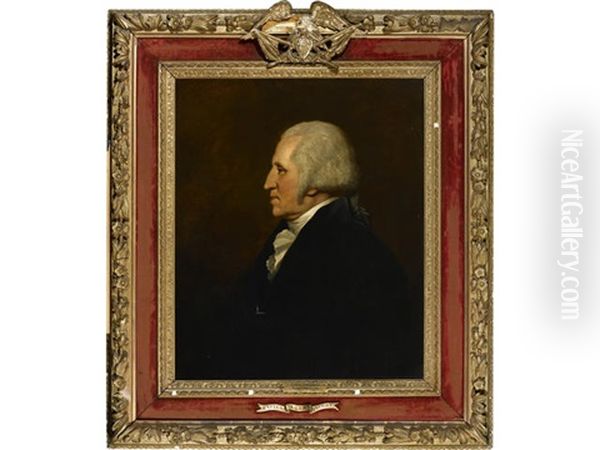

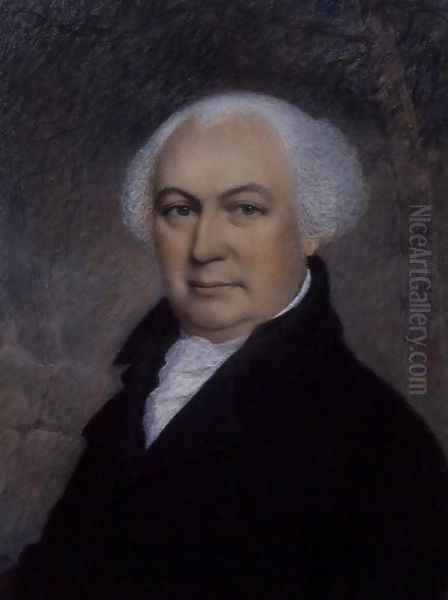

James Sharples' portraits are recognizable for their characteristic small scale, typically around 9 by 7 inches, and their frequent depiction of sitters in profile or three-quarter view. This format, combined with the speed afforded by pastels and the physiognotrace, allowed him to produce a significant number of portraits. His pastels possess a distinctive, slightly granular texture, yet they convey a softness and subtlety in the rendering of flesh tones and fabrics.

A crucial aspect of Sharples' practice was his creation of replicas. He would often retain the original pastel portrait and produce copies for the sitter or their family. These replicas were meticulously executed, often by himself or with the assistance of his artistically gifted family members. This system not only maximized his income but also disseminated his images more widely, contributing to the public's visual familiarity with important figures. This "image library" approach was a shrewd business model for an artist working in a competitive market.

His palette was generally subdued, with an emphasis on capturing a true likeness rather than overt flattery or dramatic embellishment. The grey paper he favored provided a neutral mid-tone, against which the highlights and shadows could be effectively rendered. The intimacy of the scale and the directness of the gaze in his three-quarter view portraits create a sense of personal encounter with the historical figures he depicted.

Notable Works and Esteemed Sitters

The most celebrated aspect of James Sharples' oeuvre is his gallery of American luminaries. His portrait of George Washington is perhaps his best-known work. He created several versions, both in profile and three-quarter view. These pastels offer a less idealized and perhaps more approachable image of Washington than some of the grander, more formal oil portraits by contemporaries like Gilbert Stuart or Charles Willson Peale. Sharples' Washington appears thoughtful and human, the lines of age and responsibility etched on his face.

Another key figure captured by Sharples was Alexander Hamilton. His pastel portrait of the first Secretary of the Treasury is a striking image, conveying Hamilton's intelligence and intensity. Similarly, he portrayed other foundational figures such as James Madison, Dolly Madison, Aaron Burr, and the renowned scientist and philosopher Joseph Priestley, who had also emigrated from England to America.

The demand for these portraits was high, and the Sharples family's ability to produce quality replicas ensured their widespread distribution. These images played a role in shaping the public's perception of their leaders, functioning in a way analogous to how photographs would later serve to disseminate the likenesses of prominent individuals. His sitters also included numerous senators, congressmen, and local dignitaries in cities like Philadelphia and New York.

The Sharples Family: An Artistic Dynasty

James Sharples was not the sole artist in his family; indeed, they operated almost as an artistic enterprise. His wife, Ellen Wallace Sharples (1769-1849), was a proficient miniaturist and portraitist in her own right. She meticulously copied many of her husband's pastels and also created original works. Her diaries provide invaluable insights into the family's life, travels, and artistic practice in America.

Their children also inherited artistic talent. Felix Sharples (c. 1786-c. 1824) worked in a style very similar to his father, producing pastel portraits primarily in Virginia and the southern states. James Sharples Jr. (c. 1788-1839) also became a painter, though he seems to have worked more in oils and focused on different subject matter at times. Their daughter, Rolinda Sharples (1793-1838), born shortly after the family's arrival in America, developed into a notable oil painter after the family returned to England. She became known for her ambitious group portraits and genre scenes, such as "The Cloak-Room, Clifton Assembly Rooms," a departure from the family's primary focus on individual pastel likenesses.

This familial collaboration was a significant factor in the Sharples' productivity and success. It allowed them to meet the demand for portraits and replicas efficiently, establishing a recognizable "Sharples style" that was popular and sought after.

The Artistic Landscape: Contemporaries and Competition

James Sharples operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic landscape, both in England and America. In England, the towering figures of portraiture were Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough, whose fluid brushwork and sensitivity were legendary. Sharples' teacher, George Romney, was himself a major competitor to these artists. Other notable British portraitists of the era included John Hoppner and the younger, rising star Sir Thomas Lawrence, who would come to dominate British portraiture in the early 19th century. The Scottish artist Henry Raeburn was also making a significant mark with his robust and characterful portraits.

In America, Sharples encountered a different set of contemporaries. Gilbert Stuart was arguably the preeminent portraitist of the Federal period, famed for his iconic images of George Washington, particularly the "Athenaeum" portrait. Charles Willson Peale, a veritable polymath, was not only a prolific painter but also a naturalist, inventor, and museum founder. His large artistic family, including his sons Raphaelle, Rembrandt, and Rubens Peale, also contributed significantly to American art.

John Trumbull, known for his historical paintings of the Revolution, also produced portraits of many key figures. Ralph Earl offered a distinct, somewhat more austere and linear style of American portraiture. In the realm of pastels, while Sharples was a leading practitioner in America, the medium had a rich tradition in Europe, with artists like Rosalba Carriera (earlier, but influential), Jean-Étienne Liotard, and Maurice Quentin de La Tour having elevated it to high art. In Britain, John Russell was a prominent pastelist contemporary with Sharples' earlier career. Sharples' ability to carve out a successful niche amidst such talent speaks to his skill and the appeal of his particular style and working method. He offered a product that was accessible, accurate, and relatively affordable, filling a specific need in the American market.

Later Years, Return, and Enduring Legacy

The Sharples family's time in America was not continuous. They made trips back to England, and in 1801, James and Ellen, along with Rolinda and James Jr., returned to Bath, while Felix remained in America to continue his portrait work. James Sr. seems to have divided his time, as records show him back in America.

James Sharples Sr. passed away in New York City on February 26, 1811, at the age of around 60. His death occurred while he was still actively engaged in his artistic practice. After his death, Ellen and her children Rolinda and James Jr. returned permanently to England, settling in Bristol. Ellen played a crucial role in preserving her husband's work and the family's artistic legacy. She was instrumental in the founding of the Bristol Academy for the Promotion of Fine Arts (later the Royal West of England Academy), to which she bequeathed many of the family's artworks.

James Sharples' contribution to art history lies primarily in his role as a chronicler of the early American Republic. His pastels provide an invaluable visual record of the individuals who led the nation in its formative years. While perhaps not possessing the painterly bravura of a Stuart or the grand ambition of a Trumbull, Sharples' work has an honesty and directness that is compelling. His portraits are not just historical documents; they are sensitive portrayals that capture a sense of the sitter's personality.

His use of the physiognotrace and his system of producing replicas were innovative for their time, demonstrating an entrepreneurial spirit alongside artistic skill. The Sharples family as a whole represents a fascinating example of an artistic dynasty, working collaboratively to create a significant body of work that continues to be studied and appreciated in collections such as the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery in the UK. His work remains a testament to the power of pastel to capture the essence of an individual and an era.