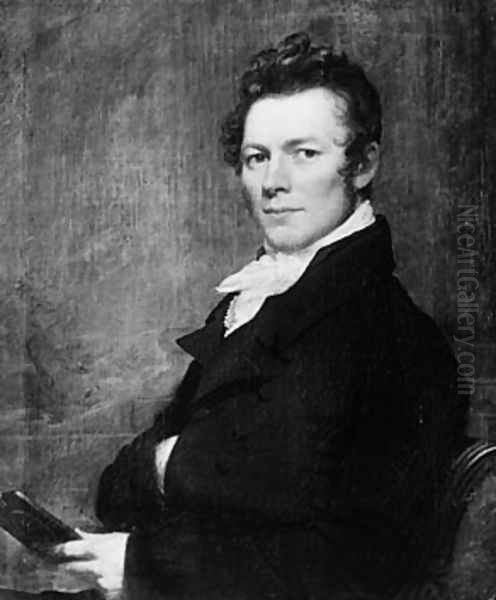

Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783-1861) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early American art, particularly renowned for his prolific career as a portrait painter. Active during a formative period for the United States, Waldo's work not only captured the likenesses of many prominent individuals but also reflected the artistic tastes and aspirations of a young nation. His journey from a Connecticut farm to the studios of London and the bustling art scene of New York City is a testament to his dedication and skill. Through his individual efforts and a long-standing, successful partnership, Waldo contributed substantially to the burgeoning American artistic tradition.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Windham, Connecticut, in 1783, Samuel Lovett Waldo hailed from a farming family, being one of eight children. His rural upbringing might have seemed distant from the world of fine arts, yet his innate talent for drawing and painting emerged at an early age. This nascent ability did not go unnoticed, and at the tender age of sixteen, Waldo made a pivotal move that would set the course for his life's work.

He traveled to Hartford, Connecticut, a regional center with a more active cultural life. There, he embarked on his formal artistic training under the tutelage of Joseph Steward, a local painter of some repute. Steward, though perhaps not a towering figure in the grand scheme of art history, provided Waldo with foundational skills and an introduction to the professional life of an artist. This apprenticeship was crucial in honing Waldo's raw talent and instilling in him the discipline required for a career in the arts.

Following his studies with Steward, Waldo sought to establish himself independently. He opened his own studio in Litchfield, Connecticut. However, the path of a young artist in early 19th-century America was often fraught with financial uncertainty. Commissions for portraits, the primary source of income for many painters of the era, were not always plentiful, especially in smaller towns. To supplement his income and make ends meet, Waldo demonstrated a practical resourcefulness, undertaking the task of painting commercial signs and advertisements. This early experience, though perhaps not artistically glamorous, underscored the pragmatic realities faced by artists of his time.

A Southern Sojourn and European Horizons

Waldo's burgeoning reputation, despite the initial challenges, began to spread. A significant opportunity arose in 1803 when he received an invitation from the Honorable John Rutledge, a distinguished figure from South Carolina. Rutledge, recognizing Waldo's talent, commissioned him to paint portraits of several successful individuals in Charleston. This venture to the South was an important step, exposing Waldo to a different regional clientele and likely bolstering both his finances and his confidence. The experience in Charleston provided him with valuable commissions and further solidified his standing as a capable portraitist.

The ambition to refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons led Waldo, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, to seek instruction in Europe, particularly in London, then a global center for art. In 1806, he embarked on this transformative journey. In London, Waldo had the invaluable opportunity to study under the guidance of some of the most celebrated artists of the day. He became a student of Benjamin West, an American-born painter who had achieved immense success in Britain, becoming the second president of the Royal Academy of Arts. West's studio was a magnet for young American artists seeking to learn from his historical paintings and portraits.

Waldo also associated with John Singleton Copley, another highly esteemed American expatriate artist known for his masterful portraits and historical scenes. Exposure to Copley's sophisticated technique and powerful characterizations would have been immensely beneficial. During his time in London, Waldo also enrolled in the Royal Academy of Arts, further immersing himself in academic traditions and contemporary artistic currents. It is noted that he shared lodgings with fellow American artist Charles Bird King, who would also go on to have a successful career in portraiture, particularly known for his depictions of Native American leaders. This period of study and interaction with leading artists in London was crucial in elevating Waldo's technical proficiency and artistic vision.

Establishing a Career in New York

Upon his return to the United States, around 1809, Samuel Lovett Waldo chose New York City as the place to establish his professional practice. New York was rapidly growing in commercial and cultural importance, offering a larger and more affluent pool of potential patrons for a portrait painter. He opened his own studio, ready to apply the skills and experience gained in London to the American market.

His timing was opportune, as the demand for portraits was increasing among the burgeoning merchant class and public figures who wished to have their likenesses preserved. Waldo's style, characterized by a solid, somewhat conservative approach and a keen eye for detail, appealed to this clientele. He quickly began to build a reputation in the city as a reliable and skilled portraitist.

It was during this early period in New York that the foundations for one of the most significant collaborations in early American art history were laid. Waldo's path would soon intersect with that of a younger artist, William Jewett, who would become his long-term partner.

The Enduring Partnership: Waldo and Jewett

Around 1809, or more formally by 1812 and certainly by 1820, Samuel Lovett Waldo began a professional association with William Jewett (1792-1874), who had initially been his apprentice. This collaboration evolved into a full-fledged partnership that would last for decades, until 1854, and become one of the most successful and recognizable artistic firms in New York: "Waldo and Jewett."

The division of labor within their partnership was a key element of their success and productivity. Generally, Waldo, as the senior and more established artist, was responsible for the most critical parts of the portrait – the face and hands of the sitter. These elements were considered paramount in capturing a likeness and conveying character. Jewett, on the other hand, typically handled the backgrounds, drapery, clothing, and other less central details of the composition. This systematic approach allowed them to produce a large volume of work efficiently without sacrificing a consistent level of quality.

Their joint signature, "Waldo and Jewett," became a hallmark of dependable, well-crafted portraiture. The firm attracted numerous commissions from prominent New Yorkers and individuals from further afield. This partnership was not unique in the history of art, but its longevity and the sheer volume of work produced made it particularly notable in the American context. It allowed both artists to leverage their strengths and build a formidable reputation that neither might have achieved as easily on their own. The success of Waldo and Jewett demonstrated a pragmatic approach to the business of art, catering effectively to the demands of their clientele.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Samuel Lovett Waldo's artistic style, both in his independent work and in collaboration with Jewett, was largely conservative and rooted in the Anglo-American portraiture tradition. His paintings are characterized by a strong emphasis on accurate likeness, clear delineation of features, and a generally smooth, polished finish. He paid considerable attention to the details of costume and setting, reflecting the status and aspirations of his sitters.

While technically proficient and capable of producing pleasing and dignified likenesses, Waldo's work has sometimes been critiqued by later art historians for a perceived lack of deep psychological insight into his subjects. Compared to some of his more romantically inclined contemporaries, such as Thomas Sully, or the penetrating character studies of Gilbert Stuart, Waldo's portraits often present a more straightforward, less interpretive depiction. His approach was often more about capturing the external appearance and social standing of the sitter rather than exploring the nuances of their personality.

However, this very quality likely contributed to his commercial success. His clients, often practical-minded merchants, politicians, and their families, sought portraits that were respectable, recognizable, and well-executed, and Waldo consistently delivered on these expectations. His palette was generally sober, and his compositions, while competent, rarely ventured into dramatic or unconventional arrangements.

Though primarily a portraitist, Waldo did occasionally venture into other genres. There is evidence, such as a letter from 1819, indicating that he and Jewett undertook sketching trips for landscape painting. This suggests an interest in the burgeoning American landscape school, though portraiture remained his and the firm's mainstay and the primary source of their reputation. His dedication to portraiture reflected the market demands of the time, where capturing the likeness of individuals held significant cultural and personal value.

Notable Works and Commissions

Throughout his long career, Samuel Lovett Waldo, often in partnership with William Jewett, produced a substantial body of work, including portraits of many distinguished individuals. Several of these works stand out and are frequently cited as representative of his oeuvre.

One of his most famous and highly praised early works is Old Pat, the Independent Beggar, painted around 1819. This painting is a character study rather than a formal commissioned portrait, depicting a well-known street figure in New York. It was lauded for its sympathetic portrayal and strong characterization, and its popularity was such that it was engraved by the prominent artist Asher B. Durand, making the image accessible to a wider public. This work demonstrated Waldo's capacity for capturing individuality beyond the confines of conventional society portraiture.

The firm of Waldo and Jewett was responsible for portraits of numerous public figures. Among these was a portrait of General Andrew Jackson, a significant commission given Jackson's national prominence, especially after the War of 1812. They also painted a Portrait of President James Monroe (circa 1824-1825), further cementing their status as painters of important American leaders. Another notable commission involved a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolution, during his celebrated return visit to the United States in the 1820s; this portrait was reportedly gifted to President Monroe.

Other representative works include the Portraits of Mr. and Mrs. David Leavitt (circa 1820-1825), which exemplify the dignified portrayal of affluent New York citizens. The Portrait of Mrs. Sackett and the Portrait of Mr. James Mackie are further examples of the consistent quality produced by the Waldo and Jewett studio. These paintings, typically solid and well-crafted, provided their sitters with enduring records of their appearance and status. Many of these works are now held in major American museum collections, attesting to their historical and artistic significance.

Waldo's Role in the American Art Community

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Samuel Lovett Waldo was an active and influential member of the burgeoning American art community. He understood the importance of institutions in fostering artistic talent and promoting the arts to the public. His involvement in several key organizations highlights his commitment to the development of a native art tradition.

Waldo was one of the founding members of the National Academy of Design in New York in 1826. This institution was established by a group of younger artists, including Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, and Samuel F.B. Morse, who sought a more artist-run and progressive alternative to the existing American Academy of Fine Arts. The National Academy played a crucial role in art education and exhibition in the United States for many decades, and Waldo's participation as a founder underscores his standing among his peers.

Interestingly, Waldo also had connections with the older American Academy of Fine Arts, which was headed for many years by the venerable painter John Trumbull. Sources indicate that Waldo served as a director of the American Academy of Fine Arts at one point. His involvement with both institutions suggests a desire to bridge different factions or, at least, a broad engagement with the organizational structures of the art world of his time. John Trumbull himself had reportedly given Waldo a letter of introduction when he first sought to establish himself, indicating an early connection with the established figures of American art.

His long and successful career, coupled with his institutional involvement, made Waldo a respected elder statesman in the New York art scene by the mid-19th century. After his death, the National Academy of Design held a memorial exhibition of his work, a tribute to his contributions as both an artist and a supporter of the arts.

Interactions with Contemporaries

Samuel Lovett Waldo's career spanned a period of significant growth in American art, and he interacted with a wide array of fellow artists. His early training with Joseph Steward and his studies in London alongside Charles Bird King under Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley have already been noted.

His most significant artistic relationship was, of course, with his long-time partner, William Jewett. However, his professional life brought him into contact with many other leading figures. The engraving of his painting Old Pat by Asher B. Durand, a prominent engraver and landscape painter of the Hudson River School, indicates a professional connection.

Waldo was a contemporary of Gilbert Stuart, arguably the most celebrated American portraitist of the preceding generation. While their styles differed, they operated within the same broad tradition. He also knew James Frothingham, another notable portrait painter who, like Waldo, produced solid, unpretentious likenesses, and Matthew Harris Jouett, a Kentucky-based portraitist who had studied with Stuart.

The mention of a "Thomas Sirse" as a collaborator in some sources is intriguing; if this is a misspelling or an anglicized version of Thomas Sully, it would point to an interaction with one of the most fashionable and romantically inclined portrait painters of the era. Sully, like Waldo, had connections to Benjamin West. If "Thomas Sirse" refers to a different, perhaps less renowned artist, it still indicates the network of collaborations and professional relationships that characterized the art world.

These interactions, whether as teacher, student, collaborator, or professional colleague, place Waldo firmly within the mainstream of early to mid-19th-century American art. He was part of a generation that worked to establish a distinctly American artistic identity, building upon European traditions while adapting them to a New World context.

Critical Reception and Legacy

The critical reception of Samuel Lovett Waldo's work has evolved over time. During his lifetime and in the decades immediately following, he and the firm of Waldo and Jewett were highly regarded for their consistent output and the reliable quality of their portraits. They were commercially successful and patronized by a wide range of clients, which speaks to the contemporary appreciation for their skill in capturing likenesses in a dignified and competent manner.

However, as artistic tastes shifted towards more Romantic or psychologically probing styles of portraiture, and later towards modernism, Waldo's more conservative and straightforward approach sometimes led to his work being viewed as solid but perhaps uninspired by some critics. The criticism that his portraits occasionally lacked deep character insight, focusing more on external representation, emerged in later art historical assessments.

The collaborative nature of his work with William Jewett also became a point of discussion. In the early 20th century, art historian Frederick Fairchild Sherman noted the difficulty in definitively distinguishing the individual hands of Waldo and Jewett in their joint works, suggesting a seamlessness in their collaboration that, while commercially effective, could blur artistic authorship.

Despite these nuanced critiques, Waldo's importance in the narrative of American art remains secure. His role as a foundational member of the National Academy of Design and his contributions to the American Academy of Fine Arts highlight his commitment to building an artistic infrastructure in the young nation. His portraits serve as invaluable historical documents, offering visual records of the individuals who shaped American society in the first half of the 19th century.

The distinction between Samuel Lovett Waldo, the painter, and another historical figure named Samuel Waldo (1695-1759), a merchant and land speculator involved in colonial-era disputes, is important to maintain. The painter's career was focused on his art and his role within the art community, and any "controversies" associated with him were generally related to art historical debates about style or attribution, rather than personal scandal.

Exhibitions, Collections, and Enduring Presence

Samuel Lovett Waldo's paintings have been featured in numerous exhibitions over the years, both during his lifetime and posthumously, reflecting his sustained significance. A notable posthumous inclusion was in the "A Century of Progress Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture" held at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1933, which showcased significant works of American and European art. His portrait of Andrew Jackson was featured in an exhibition by The Historic New Orleans Collection, illustrating Jackson's rise to national fame.

Today, works by Samuel Lovett Waldo, and by the firm of Waldo and Jewett, are held in the permanent collections of many major American museums. These include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which holds works such as his Portrait of a Man (c. 1820) and Portrait of Mrs. Edward Kellogg. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Corcoran Gallery of Art (whose collection is now largely with the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), and the Cleveland Museum of Art also count his paintings among their holdings.

The presence of his work in these esteemed institutions ensures that his contributions to American art continue to be studied and appreciated. Publications such as "Early American Paintings," "American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century, Part II," and museum catalogues like "Corcoran Gallery of Art: American Paintings to 1945" have documented his life and work for scholars and the public.

Samuel Lovett Waldo passed away on February 16, 1861, in New York City. He was buried in the New York City Marble Cemetery in the East Village, though some sources mention the Greenwich Village Cemetery; the Marble Cemetery is the more frequently cited and historically accurate resting place for prominent New Yorkers of that era.

Conclusion: An Assured Hand in a Developing Nation

Samuel Lovett Waldo carved out a distinguished and remarkably productive career in the formative years of American art. From his early training in Connecticut to his influential studies in London and his long, successful practice in New York City, he exemplified the dedicated professional artist. His partnership with William Jewett was a model of efficient and high-quality production, meeting the burgeoning demand for portraiture in a rapidly expanding nation.

While his style remained largely conservative, characterized by careful detail and a dignified representation of his subjects, his skill was undeniable and widely sought after. He captured the likenesses of presidents, generals, merchants, and everyday citizens, leaving behind a rich visual tapestry of early 19th-century American society. Beyond his easel, Waldo's commitment to fostering artistic institutions, notably as a founder of the National Academy of Design, underscores his dedication to the growth and professionalization of the arts in America. Though critical perspectives may have shifted over time, Samuel Lovett Waldo's place as a key figure in the development of American portraiture is firmly established, his works continuing to offer valuable insights into the people and the artistic culture of his era.