James William Booth (1867-1953) stands as a noteworthy figure in British art, particularly celebrated for his evocative watercolours and oil paintings. Born in Middleton, Manchester, Booth's artistic journey led him from the industrial heartlands of northern England to the rugged coastlines and pastoral landscapes that would become the primary subjects of his oeuvre. His association with the Staithes group of artists was a pivotal period, shaping his style and thematic concerns. Through his dedicated portrayal of rural life and labour, Booth carved a distinct niche, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its honesty, sensitivity, and skilled execution.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Manchester

James William Booth's formative years in Manchester, a city then at the zenith of its industrial power, likely provided a stark contrast to the rural idylls he would later choose to depict. The late 19th century was a period of significant artistic activity in provincial British cities, with burgeoning art schools and galleries fostering local talent. It was within this environment that Booth received his initial artistic training. Manchester, with its own established art scene, offered opportunities for aspiring artists to learn the foundational skills of drawing and painting.

While specific details of his earliest tutors or the exact curriculum he followed are not extensively documented, it is clear that his training in Manchester equipped him with a solid technical grounding. This period would have exposed him to various artistic currents, including the lingering influence of Pre-Raphaelitism, the academic traditions, and the burgeoning interest in more naturalistic and impressionistic approaches filtering in from continental Europe. It was also in Manchester that he forged important early friendships, most notably with Fred Jackson, an artist who would play a significant role in the next chapter of Booth's artistic development.

The decision to pursue art in an era where industrial and commercial professions were often more lauded speaks to Booth's dedication. His early works, though less known, would have likely reflected the prevailing tastes and techniques taught at the time, gradually evolving as he found his own voice and thematic preferences. The industrial landscape of Manchester, while not his primary subject later in life, may have instilled in him an appreciation for the realities of working life, a theme that would resurface in his depictions of agricultural and fishing communities.

The Staithes Experience: A Crucible of Creativity

A defining phase in James William Booth's career was his involvement with the Staithes group, an informal colony of artists situated in the picturesque fishing village of Staithes on the North Yorkshire coast. Drawn by the dramatic coastal scenery, the hardy character of the local fishing community, and the quality of the light, artists began congregating there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Booth, accompanied by his friend Fred Jackson, was among those who found inspiration in this vibrant artistic milieu.

In Staithes, Booth lived and worked in close proximity to other notable artists, including Harold Knight and Laura Johnson, who would later become Dame Laura Knight. This communal environment fostered a spirit of shared learning and artistic exploration. The artists often painted en plein air, directly from nature, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere and the daily rhythms of village life. This practice was heavily influenced by French Impressionism and the Barbizon School, as well as by earlier British landscape painters like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who had championed direct observation.

The Staithes artists, including Booth, were not a homogenous group with a single manifesto, but they shared a commitment to depicting the world around them with authenticity. Their subjects ranged from the towering cliffs and turbulent seas to the intimate scenes of fisherfolk mending nets, launching cobles (local fishing boats), or navigating the narrow village streets. Booth's time in Staithes was immensely productive. In 1901, he established his own studio at Stoneleigh Lodge, Station Road, Scalby, near Scarborough, which became a base for his continued artistic endeavours in the region. The influence of the Staithes ethos – its emphasis on realism, atmospheric effects, and the dignity of labour – would remain a cornerstone of his art. Other artists associated with the Staithes group, whose presence contributed to the creative ferment, included Rowland Henry Hill, Arthur Friedenson, and Henry Silkstone Hopwood.

Artistic Style: Realism, Impressionism, and Emotional Resonance

James William Booth's artistic style is primarily characterized by a robust realism, deeply informed by his direct observation of nature and human activity. He worked proficiently in both watercolours and oils, adapting his technique to suit the medium and the subject. While firmly rooted in the British tradition of landscape and genre painting, his work also shows an awareness of contemporary European movements, particularly French Impressionism.

The influence of Impressionism is evident in Booth's attention to light and colour. He sought to capture the transient qualities of the natural world, the play of sunlight on water, or the shifting hues of the sky. However, unlike some of the more radical French Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Booth did not dissolve form into a haze of colour and light. His commitment to realism ensured that his subjects retained their solidity and structure. His figures are often depicted with a sympathetic eye, conveying their character and the nature of their toil without overt sentimentality. This approach aligns him with social realist painters like Jean-François Millet or the artists of the Newlyn School in Cornwall, such as Stanhope Forbes and Frank Bramley, who also focused on the lives of working people.

Booth was adept at using colour not just descriptively but also to evoke mood and emotion. His palette could range from the subtle, muted tones characteristic of the North Yorkshire coast on an overcast day, to richer, more vibrant colours when depicting sunnier scenes or the warmth of an interior. His brushwork, particularly in his oil paintings, could be vigorous and expressive, adding texture and dynamism to his compositions. He paid careful attention to the details of rural life – the rigging of a boat, the harness of a working horse, the tools of a farm labourer – lending an air of authenticity to his scenes. While some contemporary observers might have found a certain directness or lack of academic polish in the work of Staithes artists, it was precisely this unvarnished quality that gave their paintings their power and truthfulness.

Thematic Concerns: The Land and Its People

The core of James William Booth's artistic output revolves around the depiction of rural and coastal life. He was a keen observer of the relationship between people and their environment, particularly those whose livelihoods were directly tied to the land or the sea. His paintings often celebrate the dignity of labour, showcasing individuals engaged in everyday tasks, from farming and harvesting to fishing and boat handling.

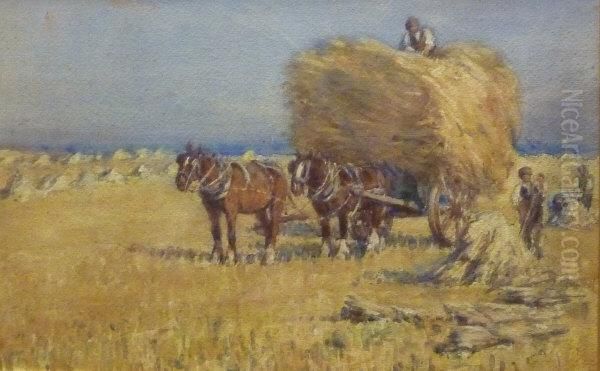

Works such as "Working Horses Hauling a Wolds Wagon" exemplify his interest in agricultural life. These scenes are not merely picturesque; they convey the physical effort involved in traditional farming practices and the close bond between humans and animals. Similarly, his coastal scenes, often set in and around Staithes or Runswick Bay, capture the challenging lives of fishing communities. He depicted the sturdy cobles, the bustling harbours, and the figures of fishermen and women, often set against the dramatic backdrop of cliffs and sea.

Booth's landscapes, whether coastal or inland, are imbued with a strong sense of place. He had a talent for capturing the specific atmosphere of a location, be it the rugged grandeur of the Yorkshire coast or the more pastoral beauty of the Irish countryside, as seen in "Glencough Ireland." His compositions are typically well-structured, leading the viewer's eye into the scene and highlighting the key elements of the narrative or a particular mood. Through his focus on these themes, Booth contributed to a broader artistic movement in Britain that sought to document and celebrate the nation's regional identities and traditional ways of life, a concern shared by artists like George Clausen and Hubert von Herkomer.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several works by James William Booth stand out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations. "Harvesting," an oil painting dated 1903, now in the Staithes Group collection, is a fine example of his agricultural scenes. Measuring 22cm x 31cm, it likely depicts the activity and machinery of a traditional harvest, possibly featuring horse-drawn carts and farm implements under a summer sky. Such a work would showcase his ability to capture a moment of intense rural activity, focusing on the figures of the labourers and the textures of the landscape.

"Cobles at Staithes with Horse and Cart on the Beckside" (24cm x 36cm) is another characteristic piece. This title immediately evokes the heart of the Staithes artistic milieu. It would portray the local fishing boats (cobles) beached or moored near the beck (stream) that runs through the village, with the common sight of a horse and cart used for transporting goods or fish. This painting would highlight Booth's skill in rendering maritime subjects and the bustling, yet often harsh, life of the fishing community. The interplay of boats, figures, and the unique architecture of Staithes would be central to its appeal.

"Up Beck to Craig Lea Runswick Bay" (35cm x 25cm) suggests a landscape focused on the natural beauty of the coastline near Staithes. Runswick Bay, another picturesque village, offered similar inspiration to artists. This work likely captures a view looking inland along a stream towards a feature named Craig Lea, showcasing Booth's ability to handle perspective and the varied textures of the coastal terrain – perhaps the gorse and heather of the cliffs, the flowing water, and the distinctive Yorkshire light. These named works, alongside others like "Glencough Ireland" and "Working Horses Hauling a Wolds Wagon," paint a picture of an artist deeply engaged with the landscapes and human stories of his time.

Artistic Circle and Collaborations

James William Booth's artistic development was significantly enriched by his interactions with fellow artists, particularly during his time with the Staithes group. His friendship with Fred Jackson was instrumental, as it was Jackson who initially led him to Staithes. Once there, the opportunity to live and work alongside Harold Knight and Laura Johnson (Dame Laura Knight) provided an environment of mutual support and artistic exchange. While formal collaborations in the sense of co-authored paintings were not typical, the shared experience of painting the same subjects, discussing techniques, and critiquing each other's work constituted a form of indirect collaboration.

The Knights were a formidable artistic duo. Harold Knight was known for his refined portraiture and interior scenes, while Laura Knight gained immense fame for her dynamic depictions of ballet, circus, and wartime life, becoming one of the most celebrated female artists in Britain. Their presence in Staithes, alongside Booth and Jackson, created a nucleus of serious artistic endeavour. The influence was likely reciprocal; Booth would have benefited from their perspectives, and they, in turn, from his. This close-knit community allowed for a rapid exchange of ideas and a collective pushing of artistic boundaries, albeit within the framework of representational art. The Staithes artists, while individual in their expressions, collectively contributed to a distinct regional school of painting, much like their contemporaries in Newlyn or later groups such as the Scottish Colourists (e.g., Samuel Peploe, F.C.B. Cadell).

Beyond Staithes, Booth's membership in organizations like the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) and the Art Club would have brought him into contact with a wider circle of London-based and national artists. Exhibiting alongside painters such as Philip Wilson Steer or Walter Sickert at RBA shows, even if their styles differed, placed him within the broader narrative of British art at the turn of the century.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

After his intensive period with the Staithes group, James William Booth continued to be a prolific artist. His studio in Scalby, established in 1901, served as his base for many years. He continued to paint subjects drawn from rural and coastal life, and his works found an appreciative audience. His paintings were exhibited in various venues, and he achieved a degree of recognition within his lifetime, evidenced by his membership in respected art societies and the sale of his works both nationally and internationally, with pieces reportedly going to collectors in Canada, Italy, and the United States.

Interestingly, later in his life, Booth's professional focus began to shift. He became increasingly involved in psychotherapy, a field that, while seemingly distant from painting, also involves a deep understanding of human emotion and experience. From the 1930s onwards, his artistic output for public exhibition seems to have lessened, with painting perhaps becoming a more personal, therapeutic activity. This dual path is not unique in the art world, where creative individuals often explore multiple avenues of expression or intellectual inquiry.

Despite this later shift, James William Booth's contribution to British art, particularly within the context of the Staithes School, remains significant. His work is valued for its authentic portrayal of a way of life that has largely vanished, its sensitive observation of nature, and its skilled craftsmanship. Posthumously, his paintings have continued to be sought after by collectors, especially those specializing in British Impressionism, social realism, or the art of the Staithes group. His legacy lies in the enduring appeal of his images, which offer a window into the landscapes and communities of early 20th-century Britain, captured with an artist's eye and a deep empathy for his subjects. He stands alongside artists like Arnesby Brown or Lucy Kemp-Welch in his dedication to rural themes, though his style was perhaps more directly influenced by the plein-air principles of the Staithes environment.

Booth in the Wider Context of British Art

To fully appreciate James William Booth's contribution, it is useful to place him within the broader currents of British art during his lifetime. The late Victorian and Edwardian periods were a time of transition and diverse artistic exploration. The academic tradition, upheld by institutions like the Royal Academy (whose prominent figures included artists like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema or Lord Leighton), still held sway, but it was increasingly challenged by newer movements.

The influence of French Impressionism, initially met with resistance, gradually permeated British art, leading to what is often termed "British Impressionism." Artists like Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert were key figures in adapting impressionistic techniques to British subjects. Booth, through his Staithes connections and his focus on light and atmosphere, can be seen as part of this broader trend, though his work retained a stronger commitment to form and narrative than some of his more avant-garde contemporaries.

The late 19th century also saw a rise in social realism, with artists turning their attention to the lives of ordinary working people. The Newlyn School in Cornwall, with painters like Stanhope Forbes, Walter Langley, and Frank Bramley, paralleled the Staithes group in its focus on fishing communities and rural labour, often employing a plein-air technique influenced by French Naturalists like Jules Bastien-Lepage. Booth's work shares thematic and stylistic affinities with these artists, contributing to a national interest in documenting regional cultures and the dignity of work.

Furthermore, the tradition of British landscape painting, stretching back to Gainsborough, Constable, and Turner, provided a rich heritage upon which Booth and his contemporaries built. The desire to capture the specific character of the British landscape, its moods, and its unique light, was a powerful motivator. Booth's dedication to the particularities of the Yorkshire coast or the agricultural Wolds places him firmly within this lineage. While perhaps not a radical innovator in the mould of, say, the Vorticists or later modernists, Booth's strength lay in his consistent and heartfelt depiction of his chosen subjects, making a valuable contribution to the rich tapestry of British art in the early 20th century.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

James William Booth was an artist of quiet dedication and considerable skill. His life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic communities and prevailing aesthetic concerns of late 19th and early 20th-century Britain. From his training in Manchester to his pivotal years with the Staithes group, and his subsequent long career, Booth remained committed to capturing the essence of rural and coastal life. His paintings, whether in watercolour or oil, are characterized by their honest observation, their sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and their empathetic portrayal of human labour.

While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his Staithes colleagues like Dame Laura Knight, Booth's contribution is nonetheless significant. He was a key member of an important regional school of painting, and his work stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of realism infused with an impressionistic sensibility. His depictions of the Yorkshire coast, the Wolds, and Irish landscapes provide a valuable historical and artistic record. Today, his paintings are appreciated for their artistic merit and for the window they offer onto a bygone era, securing James William Booth a respected place in the annals of British art.