Jan Hackaert stands as a significant figure within the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Active during the vibrant 17th century, he distinguished himself primarily as a landscape painter and etcher, celebrated for his evocative depictions of sun-drenched Italianate vistas and serene woodland scenes. Born in Amsterdam around 1628 and passing away in the same city likely around 1685, Hackaert navigated a period of immense artistic innovation, contributing a unique sensitivity to light and atmosphere that continues to captivate viewers today. His work bridges the native Dutch tradition of landscape with the popular allure of the Italian south, creating compositions that are both geographically suggestive and poetically idealized.

Artistic Formation and Influences

Emerging from the bustling artistic hub of Amsterdam, Jan Hackaert's specific training remains undocumented, a common occurrence for many artists of the period. However, the stylistic affinities in his work point strongly towards the influence of the Dutch Italianate painters, particularly Jan Both (c. 1610/18–1652) and Jan Asselijn (c. 1610–1652). These artists, who had spent time in Italy, brought back a style characterized by warm, golden light, idealized pastoral scenery, and often, classical ruins or Mediterranean motifs. Hackaert absorbed this approach, mastering the depiction of luminous, hazy atmospheres and elongated shadows cast by a low sun, which became hallmarks of his Italianate landscapes.

While embracing the Italianate aesthetic, Hackaert's work also remained grounded in the Dutch observational tradition. His meticulous rendering of foliage, the textures of tree bark, and the specific quality of light filtering through leaves demonstrate a keen eye for the natural world, akin to contemporaries focused purely on native Dutch scenery like Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629–1682) or Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709). Hackaert’s unique contribution lies in his synthesis of these influences – the atmospheric grandeur of the Italianates combined with a Dutch sensitivity to natural detail.

The Swiss Journey and Topographical Views

A pivotal episode in Hackaert's career was his journey to Switzerland, undertaken between 1653 and 1658. This trip was not merely a Grand Tour excursion but involved a specific commission from the Amsterdam lawyer and avid collector, Laurens van der Hem. Hackaert was tasked with creating detailed topographical drawings of Swiss landscapes, intended for inclusion in Van der Hem's ambitious expansion of Joan Blaeu's atlas, known today as the Atlas Blaeu-Van der Hem. These drawings, executed with remarkable precision, capture the specific geography of the Swiss Alps, showcasing Hackaert's skill in rendering complex terrains and panoramic views.

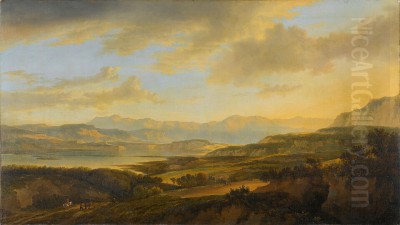

While primarily topographical, these Swiss works are far from mere cartographic records. Hackaert imbued them with artistic sensibility, carefully composing the views and employing subtle light effects. This experience likely honed his ability to handle vast spaces and complex natural forms. Interestingly, one of his most famous paintings, Lake of Zurich (c. 1660-1664, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), clearly draws inspiration from this Swiss period, presenting an idealized, expansive view of the lake bathed in his characteristic warm light. For a long time, this painting was even mistakenly identified as depicting Lake Trasimeno in Italy, a testament to Hackaert's skill in blending specific observation with an Italianate atmospheric treatment.

Italianate Landscapes: Reality and Idealization

Despite the clear Italianate flavour of many of his most celebrated paintings, concrete evidence of Jan Hackaert ever travelling to Italy remains elusive. Unlike Both or Asselijn, no documents confirm a journey south of the Alps beyond his documented stay in Switzerland. This has led to scholarly debate, but the prevailing view is that Hackaert masterfully adopted the Italianate style based on the works of his predecessors and contemporaries, possibly supplemented by prints and drawings circulating in Amsterdam. He captured the essence of the Italian Campagna – its light, its atmosphere, its pastoral tranquility – without necessarily needing to experience it firsthand.

His Italianate works, such as Landscape in the Campagna with Cattle (c. 1670, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), exemplify this approach. They feature rolling hills, umbrella pines, distant mountains often softened by haze, and the ubiquitous golden sunlight creating long, gentle shadows. Shepherds, travellers, and livestock populate these scenes, adding a sense of peaceful, timeless rural life. Hackaert’s interpretation of the Italianate mode is often gentler and more lyrical than that of some contemporaries, focusing on the harmony between nature and the figures within it. His style in these works can be compared to other Dutch artists working in the Italianate vein, such as Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683) and Karel Dujardin (1626–1678), though Hackaert often favoured purer landscapes with less emphasis on anecdotal detail.

Woodland Scenes: A Signature Genre

Alongside his Italianate views, Jan Hackaert excelled in depicting woodland interiors, a genre deeply rooted in the Dutch landscape tradition. These paintings often feature tall, slender trees forming natural avenues or clearings, with paths winding invitingly into the sun-dappled depths. Works like The Avenue of Birches (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) and The Deer-Hunt in a Wood (c. 1660, National Gallery, London) are prime examples of his mastery in this area. He possessed an exceptional ability to render the complex interplay of light and shadow beneath the forest canopy, capturing the effect of sunlight filtering through leaves and illuminating patches of the forest floor.

These woodland scenes often incorporate elements of aristocratic life, particularly hunting parties. The Deer-Hunt in a Wood, for instance, shows elegantly dressed figures on horseback engaged in the chase, adding a dynamic narrative element to the tranquil forest setting. This reflects the interests of the patrons who commissioned such works, celebrating leisure and the control over nature. Hackaert's depiction of trees is particularly noteworthy; he paid close attention to the structure of branches and the texture of bark, yet always integrated these details into a harmonious overall composition defined by light. His approach differs from the often more rugged or dramatic forest scenes of Ruisdael, offering instead a more serene and graceful vision of the woods.

Mastery of Light and Atmosphere

Perhaps Jan Hackaert's most defining characteristic is his exquisite handling of light and atmosphere. Whether depicting the warm glow of an Italian sunset or the dappled sunlight of a Dutch forest, light is never merely incidental in his paintings; it is a primary subject. He used light to unify his compositions, create depth, define form, and evoke mood. His signature golden hue, often associated with the Italianate style, imbues his landscapes with a sense of warmth, tranquility, and nostalgia.

In his woodland scenes, the treatment of light is particularly sophisticated. He captured the subtle gradations from bright, sunlit clearings to the cool, deeper shadows within the forest. This careful modulation of light guides the viewer's eye through the scene and creates a palpable sense of space and air. This sensitivity to atmospheric effects aligns him with other Dutch masters of light, such as Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691), known for his luminous depictions of the Dutch countryside, although Hackaert’s focus remained more consistently on the interplay of light within wooded or mountainous landscapes.

Collaboration in the Dutch Golden Age

Collaboration between artists specializing in different areas was a common and practical aspect of the art market in the Dutch Golden Age. Landscape painters often teamed up with figure or animal specialists to complete their compositions. Jan Hackaert frequently engaged in such collaborations, particularly for the "staffage" – the human figures and animals – that populate his landscapes. While capable of painting figures himself, relying on specialists often enhanced the appeal and value of the artwork.

His most frequent collaborators included the highly skilled Adriaen van de Velde (1636–1672), known for his elegant figures and animals, and Nicolaes Berchem. Occasionally, figures by Johannes Lingelbach (1622–1674) might also appear in his works. These collaborators would paint figures perfectly scaled and integrated into Hackaert’s landscapes, enhancing the narrative or pastoral mood. For example, the lively hunters in The Deer-Hunt in a Wood or the tranquil shepherds in his Italianate scenes were likely added by such specialists, complementing Hackaert’s masterful settings. A specific collaboration is noted for Hunting with Falcons (National Museum, Gdańsk), where the Flemish animal painter Paul de Vos (1595–1678) may have contributed. This practice highlights the interconnectedness of the artistic community and the pragmatic approaches taken to create marketable, high-quality paintings.

Hackaert as an Etcher

Beyond his significant output as a painter, Jan Hackaert was also an accomplished etcher. He produced a small but refined group of prints, primarily landscapes, which echo the themes and stylistic concerns of his paintings. His known etched work includes a series of six landscapes, demonstrating his skill in translating his sensitivity to light and texture into the linear medium of etching. These prints often depict woodland scenes, featuring his characteristic tall trees and pathways.

In his etchings, Hackaert sometimes employed a technique focusing on the foreground and middle ground, creating intimate views into the woods, sometimes referred to by the term "sous-bois" (undergrowth). This approach allows for a detailed exploration of plant life, tree trunks, and the effects of light on a smaller scale. The last known date associated with his activity appears on an etching from 1685, suggesting he continued printmaking until late in his life. These etchings, while less numerous than his paintings, form an important part of his oeuvre, showcasing his versatility and mastery across different media.

Notable Works and Collections

Jan Hackaert's paintings and drawings are held in major museum collections across the world. Some of his most representative and celebrated works include:

Lake of Zurich (c. 1660-1664, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): Perhaps his most famous painting, showcasing an idealized Swiss landscape bathed in warm, Italianate light. Its misidentification as Lake Trasimeno underscores his successful blending of geographical sources and atmospheric style.

The Avenue of Birches (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): A quintessential Hackaert woodland scene, featuring elegant birch trees forming a sun-dappled path leading into the forest interior.

The Deer-Hunt in a Wood (c. 1660, National Gallery, London): A dynamic composition combining a detailed forest setting with the lively action of a hunt, demonstrating his skill with light effects and likely collaboration on the figures.

Landscape in the Campagna with Cattle (c. 1670, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin): A fine example of his Italianate style, depicting a serene pastoral scene under a warm, hazy sky, influenced by artists like Both and Asselijn.

Wooded Landscape with a Shepherd and His Herd near a Puddle (c. 1650-1660, National Gallery, London): An etching that displays his skill in the print medium, capturing a rustic scene with attention to natural detail and atmosphere.

Topographical Drawings for the Atlas Blaeu-Van der Hem (Austrian National Library, Vienna): A significant body of work demonstrating his skill in detailed landscape rendering, commissioned during his Swiss travels.

These works, among others, secure Hackaert's reputation as a leading landscape specialist of his time. His paintings were popular among collectors, appreciated for their decorative qualities, serene moods, and technical refinement. The prevalence of woodland and hunting scenes also catered to the tastes of a wealthy clientele who valued depictions of nature and aristocratic pursuits.

Legacy and Influence

Jan Hackaert carved a distinct niche within the diverse landscape of Dutch Golden Age art. His primary contribution lies in his elegant synthesis of the native Dutch tradition of detailed natural observation with the idealized light and atmosphere of the Italianate style. He excelled at creating landscapes that felt both specific and universal, tranquil and subtly evocative. His mastery of light, particularly the rendering of sunlight filtering through trees, remains one of the most admired aspects of his work.

While perhaps not as dramatically innovative as Ruisdael or as panoramically expansive as Philips Koninck (1619–1688), Hackaert’s refined style and consistent quality earned him considerable esteem during his lifetime and beyond. His works were collected and admired, and his particular approach to woodland scenes and Italianate light likely influenced later generations of landscape painters in the Netherlands and elsewhere. He stands as a testament to the richness and variety of landscape painting during the Dutch Golden Age, an artist who skillfully navigated different stylistic currents to create a unique and enduring vision of nature. His collaborations also exemplify the workshop practices and artistic networks that characterized the period.

Conclusion

Jan Hackaert remains a compelling figure in 17th-century Dutch art. As a painter and etcher, he dedicated his career to the landscape, exploring the serene beauty of woodland interiors and the sunlit vistas inspired by Italy and Switzerland. Influenced by the Italianate masters yet retaining a Dutch sensitivity to detail, he became renowned for his masterful handling of light and atmosphere, creating scenes imbued with a gentle, poetic tranquility. Through iconic works like Lake of Zurich and The Avenue of Birches, and through his collaborations with artists like Adriaen van de Velde and Nicolaes Berchem, Hackaert left behind a significant legacy that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, harmonious compositions, and evocative portrayal of the natural world during the Dutch Golden Age.