Johannes Glauber, often referred to as Jan Glauber, stands as a significant figure in the Dutch Golden Age of painting, particularly renowned for his mastery of Italianate landscapes. Active during the latter half of the 17th century and into the early 18th century, Glauber's work reflects the enduring allure of Italy for Northern European artists, a tradition that saw painters travel south to capture the classical beauty and luminous light of the Mediterranean. His oeuvre, characterized by idealized pastoral scenes, mythological narratives set in arcadian vistas, and meticulously rendered architectural elements, places him firmly within the lineage of Dutch artists who sought to emulate the grandeur of masters like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

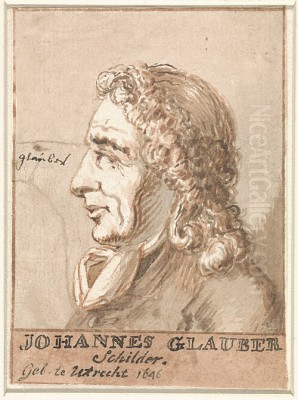

Born in Utrecht around 1646, Johannes Glauber emerged from a family with notable intellectual and, eventually, artistic inclinations. His father was the famous chemist Johann Rudolf Glauber, whose scientific pursuits, however, differed greatly from the artistic path his son would choose. Johannes, along with his brother Jan Gottlieb Glauber and sister Diana Glauber, would all pursue careers in the arts, forming a notable artistic family.

Details of Johannes Glauber's earliest training are somewhat scarce, a common challenge when reconstructing the biographies of artists from this period. However, it is widely believed that he initially studied with Nicolaes Pietersz. Berchem in Amsterdam. Berchem was himself a prominent exponent of the Italianate landscape style, known for his sun-drenched pastoral scenes populated with peasants and livestock. Training under such a master would have provided Glauber with a solid foundation in the conventions of this popular genre, including techniques for rendering atmospheric perspective, warm lighting, and the harmonious integration of figures within expansive landscapes.

The artistic environment of the Netherlands during Glauber's formative years was rich and diverse. While artists like Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals had earlier defined distinctively Dutch approaches to portraiture and genre scenes, the allure of Italy remained potent. Artists such as Jan Both, Jan Asselijn, and Herman van Swanevelt had already established the Italianate landscape as a significant and commercially successful genre, bringing back sketches and memories from their travels to inspire works created in their Dutch studios. Glauber was thus entering a field with established traditions and high standards.

The Italian Sojourn: A Pivotal Experience

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his time, Johannes Glauber recognized the importance of a journey to Italy to further his artistic education and immerse himself in the classical tradition. Around 1671, he embarked on this formative trip, a pilgrimage that would profoundly shape his artistic vision and technical skills. He is documented as having spent considerable time in Rome, the epicenter of classical antiquity and Renaissance art, and a magnet for artists from across Europe.

In Rome, Glauber would have encountered the works of the great masters firsthand. The idealized landscapes of Claude Lorrain, with their poetic light and meticulously structured compositions, and the classical narratives and heroic landscapes of Nicolas Poussin, would have been particularly influential. Poussin, though French, spent most of his career in Rome and his work became a benchmark for classically inspired landscape painting. Glauber's subsequent works clearly demonstrate an assimilation of Poussinesque principles, including balanced compositions, a sense of order, and often the inclusion of mythological or biblical figures that lend a timeless, arcadian quality to his scenes.

During his time in Rome, Glauber likely associated with the "Bentvueghels" (Dutch for "birds of a feather"), a society of mostly Dutch and Flemish artists active in Rome. This group was known for its bohemian lifestyle and for providing a network of support and camaraderie for Northern artists. While in Italy, he also reportedly worked with his brother, Jan Gottlieb Glauber, who was also a landscape painter, and the flower painter Carel de Vogelaer. This period was crucial for honing his skills in depicting the specific quality of Italian light, the characteristic Mediterranean flora, and the ruins of antiquity that so fascinated his contemporaries. He also traveled to Naples and other Italian cities, further broadening his visual vocabulary.

Travels Beyond Italy and Return to the North

After his extended stay in Italy, which lasted several years, Johannes Glauber did not immediately return to the Netherlands. His travels continued, taking him to various artistic centers where he further developed his style and connections. He is known to have worked in Lyon, France, for a period, where he collaborated with another Dutch Italianate painter, Adriaen van der Kabel. This collaboration highlights the itinerant nature of many artists' careers during this era, moving between cities and courts in search of patronage and inspiration.

Around 1680, Glauber moved to Hamburg, Germany. Here, he formed a significant artistic partnership with the painter Gerard de Lairesse and another Dutch artist, Albert Meyeringh. De Lairesse, a classicist painter and art theorist, often painted the staffage (figures and animals) in the landscapes created by Glauber and Meyeringh. This type of collaboration was common, allowing specialists to contribute their respective strengths to a single artwork. Their joint efforts in Hamburg included decorative commissions, a field in which large-scale landscape paintings were highly valued.

Following his time in Hamburg, Glauber is also recorded as having worked in Copenhagen, Denmark, further testament to his reputation and the demand for his Italianate style in various parts of Northern Europe. These experiences in different cultural contexts likely enriched his artistic practice, exposing him to diverse patronage and artistic trends.

Amsterdam, Collaborations, and Mature Style

By the late 1680s, Johannes Glauber had settled in Amsterdam, which by then was one of the wealthiest and most artistically vibrant cities in Europe. He continued his successful collaboration with Gerard de Lairesse, who had also moved to Amsterdam. Their partnership proved fruitful, with Glauber painting the expansive, idealized landscapes and De Lairesse adding the mythological or historical figures that animated these scenes.

Their joint works often adorned the grand houses of wealthy Amsterdam merchants and patricians. Notable commissions included decorative schemes for significant residences and public buildings. For instance, they collaborated on wall paintings for the Soestdijk Palace and for the country house of Jacob de Flines, where Glauber's sweeping Italianate vistas provided an elegant backdrop for De Lairesse's classical figures. These large-scale decorative projects were a hallmark of the period, transforming interior spaces into immersive, idealized worlds.

Glauber's mature style is characterized by a refined classicism. His landscapes are typically well-ordered and harmonious, often featuring serene bodies of water, majestic trees, distant mountains, and classical ruins. The light in his paintings is often warm and diffused, evoking the golden glow of the Italian countryside. While influenced by Poussin and Lorrain, Glauber developed his own distinct manner, often imbuing his scenes with a tranquil, sometimes melancholic, atmosphere. His compositions are carefully constructed, leading the viewer's eye through layers of space, from a detailed foreground to a hazy, atmospheric background.

Other Dutch Italianate painters active during or slightly before Glauber's mature period, whose works provide context for his own, include Karel Dujardin, Adam Pynacker, and Frederik de Moucheron. While each had their individual nuances, they collectively contributed to a rich tradition of depicting idealized Italian scenes for a Dutch audience that appreciated the beauty and classical associations of the South.

Glauber as an Etcher: "A Tree Struck by Lightning"

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Johannes Glauber was also a skilled etcher. His etchings, like his paintings, primarily depict landscapes. One of his most notable and frequently discussed prints is "A Tree Struck by Lightning." This work showcases his ability to capture dramatic natural phenomena and imbue a scene with a powerful emotional charge. The blasted tree, a common motif in landscape art symbolizing the sublime power of nature or the transience of life, is rendered with vigorous lines and a keen sense of light and shadow.

In his etchings, Glauber often employed a technique of cross-hatching to build up tones and create a sense of depth and atmosphere. His handling of foliage and terrain in the etched medium is confident and expressive. These prints allowed his compositions to reach a wider audience and contributed to his reputation. The influence of earlier landscape etchers, such as those from the circle of Rembrandt or Italian masters, can be discerned, but Glauber adapted these traditions to his own Poussinesque landscape vision. His etchings often mirror the compositional strategies of his paintings, featuring carefully balanced elements and a strong sense of spatial recession.

The Glauber Artistic Siblings: Jan Gottlieb and Diana

Johannes Glauber was not the only artist in his family. His brother, Jan Gottlieb Glauber (c. 1656–1703), also known as Johannes Gotlief Glauber, was a painter of landscapes as well. The two brothers reportedly traveled and worked together in Italy and later in Hamburg. Jan Gottlieb's style was similar to that of his older brother, focusing on Italianate scenes, though perhaps with subtle differences in handling or emphasis that art historians continue to study. The close working relationship between the brothers suggests a shared artistic sensibility and mutual influence.

Their sister, Diana Glauber (1650–after 1721), carved out her own artistic career, which was notable for a woman in that era. Unlike her brothers, Diana specialized primarily in portraiture and historical scenes, rather than landscapes. According to Arnold Houbraken, the early 18th-century biographer of Dutch painters, Diana Glauber was a talented artist who eventually lost her sight. Despite this tragedy, her inclusion in Houbraken's "De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen" (The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters and Paintresses) underscores her recognition as a professional artist. The presence of three practicing artists within one family, each achieving a degree of success, speaks to a supportive environment or a strong shared inclination towards the visual arts, despite their father's scientific background.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Johannes Glauber operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu. In Amsterdam, he would have been aware of the works of numerous other landscape painters. While the Italianate style was popular, other traditions also flourished, such as the more "native" Dutch landscapes of artists like Jacob van Ruisdael or Meindert Hobbema, who focused on the specific scenery and atmospheric conditions of the Netherlands.

Glauber's adherence to the classical, idealized landscapes of Poussin and Lorrain set him apart from these artists but aligned him with a significant cohort of Dutch painters who found inspiration in Italy. His collaborations, particularly with Gerard de Lairesse, were crucial. De Lairesse himself was a highly influential figure, not only as a painter but also as an art theorist whose writings, such as "Grondlegginge ter teekenkonst" (Foundations of Drawing) and "Het Groot Schilderboek" (The Great Book of Painting), promoted a classicist aesthetic based on reason, order, and the study of antiquity. Glauber's landscapes provided the perfect settings for De Lairesse's classically inspired figures and narratives.

Other artists whose careers overlapped or intersected with Glauber's include Willem van de Velde the Younger, the great marine painter, and Rachel Ruysch, a celebrated flower painter, highlighting the diversity of specializations within the Dutch art world. The patronage system, driven by wealthy merchants, civic institutions, and even foreign courts, supported this wide array of artistic production. Glauber's success in securing commissions for large-scale decorative paintings indicates his high standing within this system.

Legacy and Influence

Johannes Glauber passed away in Schoonhoven around 1726. His legacy lies in his contribution to the Dutch Italianate landscape tradition. He was a skilled synthesizer of influences, particularly those of Poussin and Lorrain, adapting their grand classical visions to the tastes of a Northern European clientele. His works are characterized by their serene beauty, technical proficiency, and harmonious compositions.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries who forged more uniquely "Dutch" styles, Glauber played an important role in perpetuating and popularizing the classical landscape. His numerous paintings and etchings found their way into collections across Europe, and his collaborations with De Lairesse were particularly significant in shaping the decorative arts of the period.

His influence can be seen in the work of later landscape painters who continued to look to Italy for inspiration. The enduring appeal of the arcadian landscape, with its connotations of a golden age and a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, owes much to artists like Glauber who so effectively translated this vision into paint and print. His works are now held in numerous museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Louvre in Paris, and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his contribution to the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age art. He remains a testament to the internationalism of art in the 17th and 18th centuries and the enduring power of the classical ideal.