Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626–1679) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century Flemish Baroque painting. Active primarily in Antwerp, he carved a unique niche for himself, specializing in meticulously detailed depictions of the natural world. His canvases, often small and executed on durable materials like copper, teem with life – vibrant flowers, iridescent insects, exotic birds, and carefully arranged fruits. As an inheritor of the esteemed Brueghel artistic dynasty, Van Kessel not only continued a family tradition of excellence but also infused it with his distinct sensibility, blending artistic virtuosity with a keen, almost scientific observation of nature. His work offers a fascinating window into the era's burgeoning interest in natural history, the culture of collecting, and the enduring appeal of still life painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

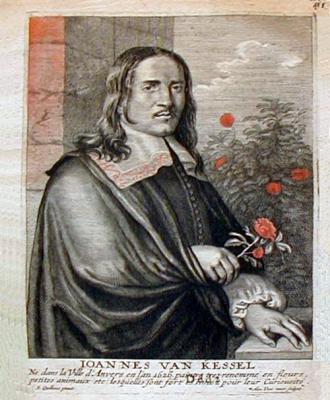

Jan van Kessel was born in Antwerp in 1626, baptized on April 5th. He entered a world already steeped in artistic tradition. His lineage was formidable: he was the grandson of the highly influential Jan Brueghel the Elder, known as "Velvet" Brueghel for his smooth finish, and the great-grandson of the legendary Pieter Bruegel the Elder, patriarch of the dynasty. His mother, Paschasia Bruegel, was Jan Brueghel the Elder's daughter, and his father was Hieronymus van Kessel the Younger, also a painter. This familial connection provided not just inspiration but likely early exposure to artistic techniques and the bustling Antwerp art market.

His formal training began around 1634/35 when he was registered as an apprentice in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke, the city's venerable institution for artists and craftsmen. His first registered master was the history painter Simon de Vos (1603–1676), known for his genre scenes and cabinet-sized historical paintings. This initial training would have provided Van Kessel with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the handling of pigments.

However, the influence of his own family, particularly his uncle Jan Brueghel the Younger (1601–1678), who had taken over his father's successful workshop, was arguably more decisive for his specialization. Jan van Kessel himself acknowledged his uncle's guidance, and records show that in 1646, he was commissioned to copy works by his uncle, indicating a close working relationship and a mastery of the Brueghelian style early in his career. By 1644/45, Jan van Kessel the Elder became a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, specifically recognized for his skill in painting flowers and, likely, the small creatures that would become his hallmark.

The Brueghel Legacy: A Foundation and a Point of Departure

The shadow and light of the Brueghel dynasty profoundly shaped Jan van Kessel's artistic identity. From Pieter Bruegel the Elder, he inherited a tradition of close observation of the world, albeit focused on the minute rather than the peasant festivals or grand landscapes his great-grandfather favoured. The more direct influence came from Jan Brueghel the Elder, whose detailed flower pieces, allegorical landscapes filled with animals, and collaborations with figures like Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) set a high standard for technical refinement and encyclopedic depiction.

Jan Brueghel the Elder's meticulous technique, often executed on copper panels to enhance the luminosity and detail, was clearly adopted by Van Kessel. The elder Brueghel's interest in compiling visual catalogues of floral species and exotic animals also resonated with Van Kessel's own fascination with the diversity of nature. Similarly, Jan Brueghel the Younger continued this tradition, running a large workshop that produced numerous works in his father's style, further embedding these themes and techniques within the family's artistic practice.

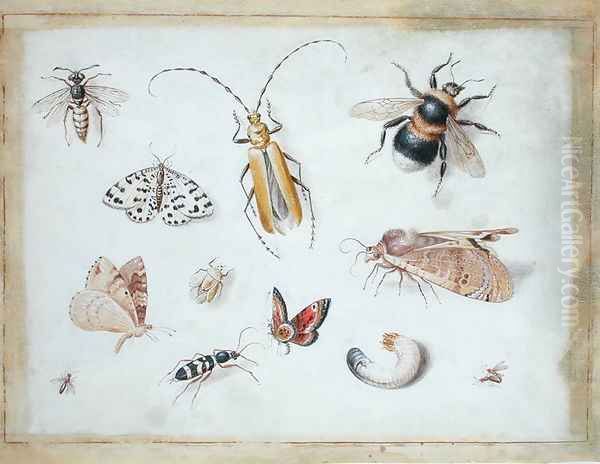

While Van Kessel operated firmly within this Brueghelian framework, he was not merely an imitator. He developed his own distinct focus, particularly on insects and small-scale compositions. While his uncles often integrated detailed natural elements into larger allegorical or landscape scenes, Van Kessel frequently made these miniature worlds the primary subject. His approach often feels more focused, isolating specimens against neutral backgrounds or arranging them in delicate, almost scientific displays, pushing the boundaries of still life towards natural history illustration while retaining artistic elegance.

Artistic Style and Techniques: Precision and Brilliance

Jan van Kessel the Elder's style is characterized by an extraordinary commitment to detail and realism, combined with a refined aesthetic sense. His technical prowess allowed him to render the varied textures, colours, and delicate structures of his subjects with remarkable accuracy.

Meticulous Realism and Detail

Van Kessel's primary achievement lies in his ability to capture the natural world with almost microscopic precision. The delicate veining on a flower petal, the iridescent sheen on a beetle's carapace, the fuzzy texture of a caterpillar, or the intricate patterns on a butterfly's wing are all rendered with painstaking care. This meticulousness suggests not only exceptional skill but also intense observation, likely aided by the use of magnifying lenses, a common tool in an era fascinated by the newly revealed complexities of the microcosm. His depictions often possess a scientific quality, making his works valuable documents of the flora and fauna known in 17th-century Antwerp.

The Medium: Copper's Allure

Like his grandfather Jan Brueghel the Elder, Van Kessel frequently chose copper panels as his support, especially for his smaller, most detailed works. Copper offered a perfectly smooth, non-absorbent surface that was ideal for fine brushwork and preserving the brilliance of pigments. Oil paint applied to copper retains a jewel-like luminosity and allows for incredibly fine detail without the paint sinking into the support, as it might with canvas or wood. This choice of medium significantly contributes to the precious, object-like quality of many of Van Kessel's paintings, enhancing their suitability as "cabinet pictures" – small, exquisite works intended for close viewing in private collections or integrated into decorative furniture.

Color and Composition

Van Kessel possessed a sophisticated understanding of colour. His palettes are often vibrant and rich, accurately reflecting the hues of the natural world. He masterfully employed subtle gradations of tone to model forms and create a sense of three-dimensionality, even on a miniature scale. He understood the power of contrast, often setting brightly coloured flowers or insects against plain, light backgrounds to emphasize their forms, or using juxtapositions of warm and cool tones, as seen in works like Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary, to create visual dynamism. His compositions, whether simple studies of single specimens or more complex arrangements, are typically balanced and elegant, guiding the viewer's eye across the intricate details with clarity.

Subject Matter and Themes: Exploring Nature's Theatre

While rooted in the still life tradition, Jan van Kessel's subject matter was diverse, consistently revolving around the detailed observation of nature but extending into allegory and occasionally religious themes.

Worlds in Miniature: Insects and Flora

Van Kessel is perhaps best known for his depictions of insects. Butterflies, beetles, moths, caterpillars, spiders, and flies populate his works, often shown alongside carefully rendered flowers, fruits, or sprigs of foliage. These are not random assortments; they often depict species found in European gardens and meadows, rendered with an accuracy that suggests direct study. Works like Butterflies, Moths and Insects with Sprays of Common Hawthorn and Forget-Me-Not exemplify this focus. These paintings served multiple purposes: as demonstrations of artistic skill, as decorative objects, and as contributions to the era's growing interest in entomology and botany. They captured the beauty and strangeness of creatures that were increasingly subjects of scientific inquiry.

His flower paintings, often small bouquets or single stems accompanied by insects, continue the tradition established by Jan Brueghel the Elder and contemporaries like Daniel Seghers (1590–1661), the Jesuit flower painter. Van Kessel depicted popular blooms like roses and tulips, but also humbler wildflowers, always with his characteristic precision. These works often carried symbolic weight – flowers representing transience (Vanitas), divine creation, or specific virtues – though Van Kessel's primary focus often seems to be the accurate and beautiful representation of the specimen itself.

Allegory and Symbolism: Beyond Surface Beauty

Van Kessel also engaged with more complex allegorical themes, often using his mastery of natural detail to convey broader ideas. His most ambitious project in this vein is the series known as The Four Continents (Europe, Asia, Africa, and America), typically painted as a set of small pictures, often on copper. Each panel presents a symbolic landscape filled with the representative animals, plants, and sometimes ethnographic details associated with that continent. For example, The Four Continents: Europe might feature horses, cattle, local birds, and European cityscapes or harbours in the background, while Africa would showcase elephants, lions, crocodiles, and exotic birds.

These series were highly sought after and reflected the 17th-century European fascination with global exploration, trade, and the cataloguing of the known world. They functioned as miniature encyclopedias, bringing the wonders of distant lands into the collector's cabinet. Beyond the geographical representation, these works could also carry allegorical meanings related to the elements, the senses, or the harmony (and sometimes dangers) of the natural world. The meticulous rendering of each creature and plant underscores the richness and diversity of creation, a common theme in Baroque art.

Symbolism was often subtly embedded even in simpler still lifes. Insects, particularly flies or caterpillars, could symbolize decay, corruption, or the brevity of life, linking these works to the Vanitas tradition. Butterflies, emerging from a chrysalis, could represent resurrection or the soul's transformation. Fruits, depending on their state, might signify abundance, fertility, or the inevitable process of ripening and decay. While Van Kessel's work often prioritizes visual accuracy, these layers of meaning would have been readily understood by his contemporary audience.

Religious and Mythological Undertones

While less common than his natural history subjects, Van Kessel did occasionally incorporate religious or mythological themes, often within his characteristic framework. He painted garland pictures, a genre popular in Antwerp where a central religious scene, often painted by another artist, was surrounded by an elaborate wreath of flowers, fruits, and sometimes insects painted by a specialist like Van Kessel. An example is the Holy Family in a Garland. These works combined devotional imagery with a celebration of nature's beauty, seen as God's creation. He also produced works depicting scenes like Noah's Ark or Orpheus charming the animals, which provided ample opportunity to showcase his skill in rendering diverse fauna.

Science and Art: A Symbiotic Relationship

Jan van Kessel's art is deeply intertwined with the scientific currents of his time. The 17th century witnessed significant advances in natural history, spurred by global exploration, the development of microscopy, and a systematic approach to classification. Van Kessel's work reflects and participates in this "Age of Observation."

His detailed insect studies, in particular, align with the burgeoning field of entomology. His accuracy suggests familiarity with, or at least a shared spirit with, the illustrated natural history books and manuscripts that were becoming increasingly sophisticated. The influence of earlier scientific illustrators, such as the meticulous work of Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601), whose illuminated manuscripts included stunningly precise depictions of insects and plants, is evident in Van Kessel's approach. Hoefnagel's work, particularly the Four Elements manuscript and his contributions to Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg's atlas Civitates Orbis Terrarum, set a precedent for combining artistic skill with scientific documentation.

Van Kessel's paintings often resemble the display cases of a "cabinet of curiosities" (Wunderkammer), popular among European elites. These collections housed natural specimens (shells, insects, minerals), exotic artifacts, scientific instruments, and artworks, representing a microcosm of the world and human knowledge. Van Kessel's small, detailed panels, especially series like The Four Continents or sets depicting various insects or shells, were perfectly suited for such environments, functioning both as precious objects and as visual catalogues of natural wonders. His art thus catered to and fueled the period's passion for collecting, classifying, and marveling at the diversity of the natural world. One anecdote even suggests he sometimes playfully arranged insects in his compositions to form his initial "J," a testament to his wit and integration of subject and signature.

Major Works and Commissions

While attributing specific dates to many of Van Kessel's works can be challenging, several stand out as representative of his oeuvre and achievements.

His series depicting The Four Continents are among his most celebrated works. Multiple versions exist, showcasing his ability to handle complex compositions teeming with diverse fauna and flora specific to each region, often set against miniature landscapes. These series, typically painted on copper, are found in major collections like the Prado Museum in Madrid and the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

Numerous small panels dedicated to insects survive, demonstrating his specialization. Butterflies, Moths and Insects with Sprays of Common Hawthorn and Forget-Me-Not (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) is a prime example, showcasing delicate insects arranged with botanical elements against a light background. Similar studies, sometimes focusing on beetles, spiders, or caterpillars, highlight his observational prowess and technical finesse. Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) is another exquisite example of this genre.

His flower pieces, while perhaps less numerous than his insect studies, are equally refined. They range from small bouquets in glass vases to single stems acting as perches for insects. These works demonstrate his connection to the broader tradition of Flemish flower painting, alongside artists like Jan Philips van Thielen (1618–1667).

Van Kessel also received prestigious commissions. Notably, he worked for the Spanish court. Records indicate he painted studies of animals and insects for King Philip IV of Spain, a testament to his international reputation and the desirability of his specialized skills. This royal patronage underscores the high esteem in which his detailed natural history paintings were held.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

The Antwerp art scene in the 17th century was highly collaborative, and Jan van Kessel participated in this practice. While primarily known for his independent work, he is believed to have collaborated with other artists, particularly figure painters who might add staffage or central scenes to his detailed natural settings or garlands.

His most significant artistic relationships were within his own family – the guidance from Jan Brueghel the Younger was crucial. He also likely interacted with the wide circle of artists associated with the Brueghel workshop and the broader Antwerp school. This included painters specializing in various genres, such as the leading animal painters Frans Snyders (1579–1657) and Jan Fyt (1611–1661), whose work, though often on a larger scale, shared an interest in accurately depicting fauna.

There is evidence of collaboration with figure painters like his contemporary David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690), who himself married into the Brueghel family (Anna Brueghel, daughter of Jan Brueghel the Elder). Teniers was known for his peasant scenes, landscapes, and gallery paintings. Collaboration might have involved Van Kessel adding detailed still life elements or natural history details to Teniers' compositions, or vice versa. He is also documented as having collaborated with Erasmus Quellinus II (1607–1678), a prominent history painter who often worked with specialists for elements like flowers or architecture. The mention of collaboration with a "Quentin Matsys II" likely refers to a descendant or follower of the famous 16th-century painter Quentin Metsys, possibly Quentin Metsys the Younger, though details remain scarce. These collaborations highlight the integrated nature of art production in Antwerp, where specialists often combined their skills to create complex works.

Later Life and Legacy

Jan van Kessel the Elder remained active in Antwerp throughout his career. He married Maria van Apshoven in 1647, and they had thirteen children. Two of his sons, Jan van Kessel the Younger (1654–1708) and Ferdinand van Kessel (1648–1696), also became painters, continuing the family tradition. Jan the Younger eventually moved to Spain and became a court painter, while Ferdinand largely worked in his father's style, sometimes making distinguishing between their works challenging.

Despite his success and prestigious connections, Jan van Kessel the Elder appears to have faced financial difficulties later in life, reportedly needing to mortgage his home. He passed away in Antwerp in 1679 at the age of 53, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continued to be appreciated by collectors.

His legacy is significant. He represents a unique fusion of the Brueghelian tradition with the burgeoning scientific naturalism of the Baroque era. His meticulous technique, particularly on copper, set a standard for detailed still life painting. He excelled in the specialized niche of insect and small animal painting, creating works that were both aesthetically pleasing and informative. His influence can be seen in the work of his sons and potentially other Antwerp painters specializing in similar subjects. More broadly, his art exemplifies the 17th-century fascination with the natural world, the culture of collecting, and the intricate beauty found in the smallest corners of creation. His works remain highly prized today, found in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre, the Prado, the Hermitage, the Rijksmuseum, and many others, continuing to captivate viewers with their miniature marvels.

Conclusion: An Enduring Fascination

Jan van Kessel the Elder was more than just a painter of flowers and insects; he was a visual poet of the microcosm. Rooted in the illustrious Brueghel dynasty, he forged his own path, dedicating his exceptional technical skills to capturing the intricate beauty and diversity of the natural world. His paintings on copper gleam with jewel-like precision, inviting viewers into a world where the smallest creatures are rendered with monumental care. Balancing artistic elegance with scientific accuracy, his work resonated with the intellectual and aesthetic currents of the 17th century, finding favour with collectors and royalty alike. From the allegorical scope of The Four Continents to the intimate focus of a single butterfly on a flower stem, Van Kessel's art continues to inspire wonder, reminding us of the rich complexities hidden in plain sight and the enduring power of meticulous observation married to artistic vision. He remains a key figure in Flemish Baroque art, a master whose miniature worlds contain universes of detail.