Balthasar van der Ast stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Renowned for his exquisite still lifes, particularly those featuring flowers, fruits, and shells, he bridged the gap between the pioneering work of his predecessors and the more elaborate compositions that followed. His meticulous technique, keen eye for detail, and subtle infusion of symbolism cemented his place as a leading artist of his time, whose influence extended to subsequent generations of painters. His life and career unfolded across several key artistic centers in the Netherlands, reflecting the dynamic cultural environment of the 17th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Middelburg

Balthasar van der Ast was born in Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland, likely in 1593 or 1594. Middelburg, at the turn of the 17th century, was a prosperous trading city, benefiting from the activities of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). This environment provided access to exotic goods, including rare shells and flowers, which would later become prominent motifs in Van der Ast's work. His family background was comfortable; his father, Hans van der Ast, was a successful wool merchant.

Tragedy struck early in Balthasar's life. His father passed away in 1609, leaving the young Balthasar, then around fifteen or sixteen years old, effectively orphaned. Following this loss, he moved in with his elder sister, Maria, and her husband, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621). This move proved pivotal for his artistic development. Ambrosius Bosschaert was already an established and highly respected painter, considered one of the founders of Dutch floral still life painting.

Under the tutelage of his brother-in-law, Van der Ast received his foundational training in the art of still life. Bosschaert's studio was a thriving family enterprise, and Balthasar learned alongside Ambrosius's own sons, Ambrosius the Younger, Johannes, and Abraham Bosschaert, who also became still life painters. The elder Bosschaert's style, characterized by symmetrical compositions, bright illumination, meticulous detail, and often featuring rare and expensive flowers depicted with botanical accuracy, profoundly shaped Van der Ast's early work.

Utrecht: A Period of Growth and Recognition

In 1615, the Bosschaert family, including Balthasar van der Ast, relocated from Middelburg to Bergen op Zoom. Their stay there was relatively brief. By 1619, Van der Ast had moved again, this time settling in Utrecht, a major artistic hub in the Netherlands. In the same year, he was documented as joining the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen. Membership was essential for establishing an independent workshop, taking on pupils, and selling work legally.

Utrecht offered a vibrant artistic milieu. While the city was known for the Utrecht Caravaggisti, painters like Gerard van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen who were influenced by the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, Van der Ast remained focused on still life. However, he did absorb influences from other artists active in the city. Notably, the work of Roelandt Savery (1576-1639), another prominent still life painter who had also moved to Utrecht around the same time, seems to have impacted Van der Ast.

Savery, who had previously worked at the imperial court in Prague, often incorporated a wider variety of elements into his compositions, including animals and insects, and sometimes employed a slightly softer, more atmospheric approach to light and texture compared to the crisp precision of Bosschaert. Exposure to Savery's work likely encouraged Van der Ast to broaden his own subject matter and experiment with composition and tonality, moving gradually away from the stricter symmetry of his early training. During his Utrecht period, Van der Ast established himself as an independent master and began developing his distinct artistic voice.

Delft: Maturity and Later Works

In 1632, Balthasar van der Ast made his final significant move, relocating to the city of Delft. Delft was another important center for the arts and sciences, famous for its pottery (Delftware) and home to artists like Johannes Vermeer (though Vermeer's main activity came slightly later). Van der Ast would remain in Delft for the rest of his life. He married Margrieta Jans van Buijeren in Delft in February 1633, and they had at least two children.

His time in Delft marks the mature phase of his career. His compositions often became more complex and dynamic than his earlier works. While maintaining his characteristic precision, he explored asymmetrical arrangements and a greater sense of depth. He continued to specialize in still lifes featuring flowers, fruits, and shells, but his arrangements grew more ambitious, often depicting lavish collections of objects spread across a ledge or table.

The inclusion of exotic shells, sourced through the Netherlands' extensive global trade network, became even more prominent in his Delft period. These shells were highly prized collector's items, symbols of wealth and worldliness, and Van der Ast rendered their intricate patterns and iridescent surfaces with extraordinary skill. He is often credited as being a pioneer in the specialized genre of shell painting. His Delft workshop was successful, and he continued to paint prolifically until his death. Balthasar van der Ast passed away in Delft and was buried in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) on March 7, 1657.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Balthasar van der Ast's style is defined by its meticulous realism and exquisite detail. Working within the tradition established by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, he depicted objects with almost scientific precision. Every petal, leaf, insect wing, and shell surface is rendered with painstaking care. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the diverse textures of his subjects – the velvety softness of a peach, the delicate translucency of grape skin, the hard, glossy sheen of a beetle's carapace, or the intricate, pearlescent interior of a seashell.

His use of light is typically clear and even, illuminating the objects sharply against a neutral, often dark background, which helps to emphasize their form and colour. While influenced by Bosschaert's often symmetrical arrangements early on, Van der Ast increasingly favoured more dynamic, diagonal compositions in his mature work. He skillfully arranged objects to create a sense of depth and spatial recession, often using overlapping forms and placing items on different planes.

A distinctive feature of Van der Ast's work is his frequent inclusion of small creatures alongside the primary subjects. Insects like butterflies, dragonflies, beetles, and flies, as well as lizards, spiders, and even small birds, populate his still lifes. These are not mere decorative additions; they add life and narrative interest to the scenes and often carry symbolic weight. He was also known to occasionally paint on copper panels, a smooth surface that allowed for an even finer degree of detail than traditional wood panels.

Thematic Depth: Symbolism and Science

Like many Dutch still lifes of the Golden Age, Van der Ast's paintings operate on multiple levels. Beyond their surface beauty and technical brilliance, they often contain layers of symbolism, particularly related to the concept of vanitas. The Dutch Republic was predominantly Calvinist, and while overt religious imagery was less common in domestic art than in Catholic countries, moralizing themes were frequently embedded in seemingly secular subjects.

Flowers, in their peak bloom, represented beauty and life, but inevitably they wilt and fade. Van der Ast often included flowers past their prime, or insects known for their short lifespans (like butterflies emerging from caterpillars), subtly reminding the viewer of the transience of earthly existence and the fleeting nature of beauty and worldly possessions. The expensive tulips, exotic shells, and imported fruits could symbolize wealth and luxury, but also the vanity of pursuing such ephemeral goods.

At the same time, Van der Ast's work reflects the burgeoning scientific curiosity of the era. The 17th century saw significant advances in botany, entomology, and natural history. Wealthy Dutch citizens often maintained "cabinets of curiosities" (Kunstkammer or Wonderkammer), collections of natural specimens (like shells, minerals, insects) and man-made objects. Van der Ast's detailed depictions of specific flower species, identifiable insects, and accurately rendered exotic shells catered to this interest in the natural world. His paintings served not only as beautiful objects but also as visual encyclopedias, celebrating the diversity and wonder of creation while simultaneously hinting at its impermanence.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Balthasar van der Ast produced a considerable body of work during his career. Several paintings stand out as representative of his skill and style:

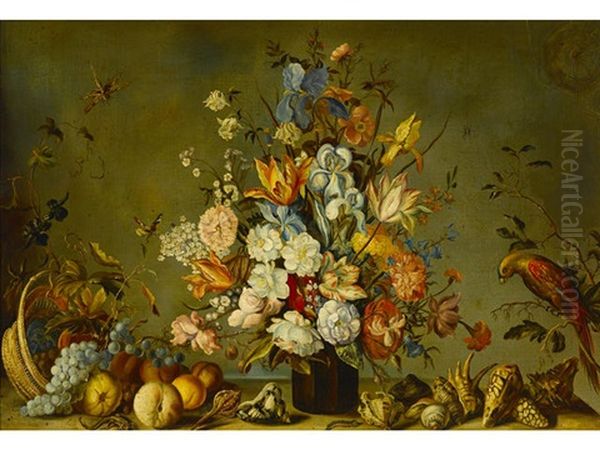

_Still Life with Flowers and Fruit_ (c. 1620-21, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): An early work likely from his Utrecht period, this painting shows the influence of Bosschaert in its clarity and detailed rendering. It features a basket overflowing with various fruits and a vase filled with an assortment of flowers, including tulips, roses, and irises, accompanied by shells and insects.

_Basket of Flowers_ (1622, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): This work exemplifies his Utrecht style. A wicker basket holds a profusion of flowers from different seasons – tulips, roses, carnations, columbines, forget-me-nots – rendered with exquisite detail. Shells and insects are scattered on the stone ledge below, adding points of interest and symbolic depth. The composition is relatively symmetrical but already shows Van der Ast's developing complexity.

_Basket of Fruits_ (1632, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): Painted around the time he moved to Delft, this piece showcases his mastery in depicting fruit textures. Grapes, peaches, apples, and cherries fill a basket, accompanied by flowers, shells, and insects. The handling of light creates a sense of volume and realism.

_Still Life with Shells_ (Various dates and collections): Van der Ast painted numerous works focusing primarily on shells. These paintings highlight his fascination with these exotic objects from distant shores, capturing their diverse shapes, colours, and textures with remarkable fidelity. Examples can be found in museums like the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and the Mauritshuis, The Hague.

_Still Life with Fruit and Flowers_ (c. 1620s, Mauritshuis, The Hague): This painting is a quintessential example of his ability to combine diverse elements into a harmonious whole. A Wanli porcelain bowl, another luxury import, holds fruit, while flowers spill from a vase. Shells, insects, and even a lizard populate the scene, creating a microcosm of the natural world, both beautiful and potentially perilous (symbolized by the lizard or certain insects).

_Basket of Fruit and a Vase of Flowers with Shells in a Niche_ (c. 1640-45, Tate, London): A later work from his Delft period, this painting demonstrates his mature style with a more complex, asymmetrical arrangement within a stone niche, enhancing the sense of depth. The variety of objects and the interplay of light and shadow are handled with confidence and sophistication.

These examples illustrate Van der Ast's consistent themes and evolving style, showcasing his dedication to the meticulous representation of the natural world, infused with symbolic meaning.

Influence and Legacy

Balthasar van der Ast played a crucial role in the development of Dutch still life painting. As a direct artistic heir to Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, he carried forward the Middelburg tradition of precise, brightly lit flower painting. However, he did not merely imitate his master; he expanded the genre's possibilities by incorporating a wider range of objects, particularly shells and insects, and by developing more complex and dynamic compositions.

His most significant pupil was Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684), who likely studied with him in Utrecht. De Heem became one of the most influential still life painters of the entire Dutch Golden Age, known for his lavish and opulent compositions (pronkstilleven). While De Heem developed his own distinct style, the meticulous attention to detail and the combination of flowers, fruit, and other objects found in Van der Ast's work clearly provided a foundation. Some of De Heem's early works show a strong affinity with Van der Ast's style.

Van der Ast's influence also extended to his nephews, the sons of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder – Ambrosius the Younger (1609-1645), Johannes (c. 1607-1628/9), and Abraham (1612/13-1643) – who continued the family tradition of still life painting, often working in styles closely related to both their father and their uncle/teacher.

Furthermore, Van der Ast's work, alongside that of Bosschaert and Roelandt Savery, helped establish Utrecht as an important center for still life painting in the early 17th century. His detailed depictions of shells likely influenced other artists who specialized in this subgenre. His broader impact lies in his contribution to the vocabulary and refinement of Dutch still life, demonstrating how careful observation, technical skill, and subtle symbolism could elevate everyday objects to high art. His paintings were appreciated by collectors in his own time and continue to be admired for their beauty and craftsmanship.

Van der Ast and His Contemporaries

Understanding Balthasar van der Ast requires placing him within the context of his contemporaries. His primary artistic relationship was with his teacher and brother-in-law, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder. Bosschaert provided his initial training and stylistic template. The works of the early Flemish pioneers of still life, such as Osias Beert (c. 1580-1624) and Clara Peeters (fl. 1607-1621), also form part of the background against which the Dutch tradition emerged. Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) in Antwerp was immensely influential with his elaborate floral bouquets, setting a high standard for detail and composition that resonated across the Low Countries.

In Utrecht, Roelandt Savery was a key contemporary whose slightly looser, more atmospheric style and inclusion of diverse fauna offered a different approach to still life, likely prompting Van der Ast to experiment. While the Utrecht Caravaggisti like Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) and Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629) focused on dramatic figure painting, their presence contributed to the city's artistic dynamism. Van der Ast also taught Jan Davidsz. de Heem, linking him directly to the next generation of leading still life painters.

In Delft, Van der Ast worked alongside other artists, although direct stylistic links in still life are less pronounced than in Utrecht. Jacob Vosmaer (c. 1584-1641) was another Delft painter known for flower pieces, though his style differed. The city later became famous for Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and Carel Fabritius (1622-1654), but their focus on genre scenes and portraiture, respectively, places them in different artistic spheres, despite sharing the same urban environment during Van der Ast's later years. Comparing Van der Ast to the Haarlem still life painters like Pieter Claesz. (c. 1597-1660) and Willem Claesz. Heda (1594-c. 1680), known for their monochrome banquet pieces ('ontbijtjes'), highlights the diversity within Dutch still life during this period. Van der Ast's colourful, detailed arrangements stand in contrast to their more tonal and restrained compositions. Later flower painters like Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) and Jan van Huysum (1682-1749) would build upon the foundations laid by artists like Van der Ast, taking floral painting to new heights of complexity and decorative elegance.

Collecting Van der Ast: Museum Holdings

Works by Balthasar van der Ast are held in numerous prestigious museums and private collections around the world, attesting to his enduring appeal and historical importance. Key public collections include:

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: Holds significant works like Still Life with Flowers and Fruit (c. 1620-21).

Mauritshuis, The Hague: Features important examples, including Still Life with Fruit and Flowers (c. 1620s) and notable shell still lifes.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.: Possesses key works such as Basket of Flowers (1622) and Basket of Fruits (1632), both from the Paul Mellon collection.

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles: Includes fine examples of his flower and fruit still lifes.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: Holds several works, including notable shell paintings.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: Also part of the University of Cambridge, it houses examples of his still lifes.

Tate, London: Collection includes the later work Basket of Fruit and a Vase of Flowers with Shells in a Niche (c. 1640-45).

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (Gemäldegalerie): Owns works like Still Life with Apple Blossom (1635).

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm: Collection includes Still Life with Basket of Flowers (c. 1630s).

St. Louis Art Museum: Holds Still Life with Shells and Flowers (1622).

Baltimore Museum of Art: Features a Bouquet of Tulips, Carnations, and Roses, with Shells and Insects on a Ledge.

Louvre Museum, Paris: Also includes examples of his work in its extensive collection of Northern European painting.

The presence of his paintings in these major institutions underscores his status as a canonical artist of the Dutch Golden Age. His works are frequently included in exhibitions focusing on Dutch art, still life painting, and the intersection of art and science in the 17th century.

Conclusion

Balthasar van der Ast was more than just a painter of pretty flowers and shells. He was a highly skilled technician, a keen observer of the natural world, and an artist who imbued his works with subtle layers of meaning relevant to his time. Emerging from the influential Bosschaert workshop, he forged his own path, contributing significantly to the evolution of still life painting in the Dutch Republic. His meticulous detail, vibrant colours, complex compositions, and pioneering depiction of shells secured his reputation during his lifetime and ensured his lasting legacy. As a bridge between early pioneers and later masters like De Heem, and as a reflection of the Dutch Golden Age's fascination with both global trade and the natural world, Balthasar van der Ast remains a captivating and important figure in the history of art.