Jean Antoine Linck stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the annals of Swiss art, particularly renowned for his evocative and scientifically astute depictions of the Alpine landscapes that dominated his homeland. Active during a transformative period in European art and thought—the late 18th and early 19th centuries—Linck's work bridged the meticulous observation of the Enlightenment with the burgeoning sensibilities of Romanticism. His legacy is twofold: as an artist who captured the majestic beauty and awe-inspiring power of the Alps, and as a diligent chronicler whose images provide invaluable insights into the historical state of glaciers, making him an unwitting contributor to early glaciological studies.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Geneva

Jean Antoine Linck was born on December 14, 1766, in Geneva, a city already establishing itself as a vibrant cultural and intellectual hub. His artistic journey began in a familial setting steeped in creative pursuits. His father, Jean Conrad Linck, was an accomplished enameller and engraver. It was within his father's workshop that the young Jean Antoine received his foundational training, immersing himself in the demanding disciplines of enamel painting and copperplate engraving from the tender age of twelve. This early exposure to techniques requiring precision and a keen eye for detail would profoundly shape his later artistic endeavors, particularly his landscape work.

The environment of Geneva during Linck's formative years was crucial. The city was a crossroads of ideas, influenced by thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose writings extolled the virtues of nature and the emotional responses it could evoke. Furthermore, the proximity of the Alps, with their dramatic peaks and mysterious glaciers, was beginning to attract intrepid travelers, scientists, and artists, shifting the perception of mountains from terrifying obstacles to objects of sublime beauty and scientific inquiry. This cultural milieu undoubtedly nurtured Linck's burgeoning interest in the natural world.

The Call of the Mountains: Subject and Inspiration

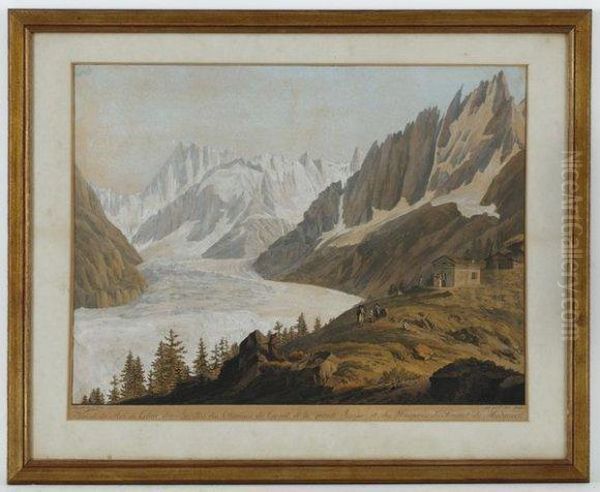

While his initial training encompassed various artistic forms, Jean Antoine Linck found his true calling in the depiction of the Alpine wilderness. He became particularly celebrated for his views of the Savoy Alps and their formidable glaciers. His gaze was repeatedly drawn to the iconic Mont Blanc massif, the highest peak in the Alps, and its surrounding ice-flows, such as the Glacier des Bois (the tongue of the Mer de Glace) and the Grindelwald glaciers (though the Schwarzwald Glacier mentioned in some sources is more typically associated with the Bernese Alps, Linck's focus was predominantly on the Mont Blanc region).

Linck's dedication to his subject was not casual. He undertook numerous expeditions into the high mountain valleys, often during the summer months, to sketch directly from nature. These plein-air studies, filled with firsthand observations of light, form, and atmospheric conditions, would later serve as the basis for more finished works executed in his studio. This practice of direct observation was characteristic of a new wave of landscape artists who sought authenticity and a deeper connection with their subjects, moving away from the idealized or purely imaginary landscapes of earlier traditions. His commitment was akin to that of early explorers and scientists like Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, whose pioneering ascents of Mont Blanc in the 1780s captivated Europe and further fueled artistic interest in the Alpine realm.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Precision and Poetic Vision

Jean Antoine Linck’s artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of meticulous realism and a burgeoning Romantic sensibility. His early training in engraving and enamel work instilled in him a profound respect for detail and accuracy. This is evident in the precise rendering of geological formations, the careful delineation of glacial structures, and the almost topographical exactitude of his mountain panoramas. His works often convey a strong sense of place, allowing viewers to identify specific peaks and valleys.

However, Linck was more than just a topographical draughtsman. He imbued his landscapes with a palpable atmosphere and a sense of the sublime. He masterfully employed mediums such as black and white pencil, ink, and white chalk, often on tinted paper, to create dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, highlighting the monumental scale and rugged textures of the mountains. His watercolors and gouaches, in particular, allowed for a nuanced depiction of the ethereal light and subtle color shifts characteristic of Alpine environments.

While artists like Caspar Wolf (1735-1783) had earlier pioneered Alpine landscape painting in Switzerland with a dramatic, often proto-Romantic flair, Linck built upon this foundation, refining a style that balanced scientific curiosity with aesthetic appreciation. His approach can be contrasted with the more overtly dramatic and sometimes turbulent Alpine scenes of later Romantics like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), who also famously painted the Swiss Alps. Linck’s Romanticism was often quieter, more contemplative, emphasizing the serene grandeur and timeless majesty of the mountains, though the inherent power of his subjects was always present. He shared with contemporaries like the German Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) a sense of nature's spiritual depth, though Linck's focus remained more on the observable reality of the landscape.

Masterpieces and Key Works: A Visual Journey

Jean Antoine Linck's oeuvre includes several works that are considered representative of his skill and vision. Among these, the series or individual pieces titled _Vue de la mer de Glace_ (View of the Sea of Ice) are particularly prominent. The Mer de Glace, a vast glacier flowing down from the Mont Blanc massif, was a popular subject for artists and travelers, and Linck depicted it numerous times, capturing its crevassed surface and the imposing peaks surrounding it. One version, specifically dated to 1820, is noted for its historical value in documenting the glacier's extent at that time. These views are often considered among his masterpieces, showcasing his ability to convey both the glacier's immense scale and its intricate details.

Another significant work, or series, is _Glaciers, rocs, lumière_ (Glaciers, Rocks, Light), reportedly a triptych created between 1799 and 1820. This title itself encapsulates the core elements of Linck's fascination: the interplay of solid geological forms, the dynamic nature of ice, and the transformative effects of light in the high Alps. Such a work would have allowed him to explore different facets of the Alpine environment in a connected narrative or thematic grouping.

Other notable titles include _Vue de l'Alpe en sommeil_ (View of the Sleeping Alp), which suggests a more tranquil, perhaps pastoral, depiction of the mountain landscape, possibly capturing a moment of stillness or a less rugged aspect of the Alps. _Vue de la cascade d'Arpenas_ (View of the Arpenas Waterfall) indicates his interest in other dramatic natural features beyond glaciers and peaks. Waterfalls were a common motif in Romantic landscape painting, symbolizing the untamed power and beauty of nature, a subject also explored by artists like the Swiss-born Abraham-Louis-Rodolphe Ducros (1748-1810) in his Italian and Swiss scenes.

His various depictions titled _Vue du Mont Blanc_ (View of Mont Blanc) would have been central to his output, given the peak's iconic status. These works would have demonstrated his skill in capturing the complex topography and atmospheric conditions surrounding Europe's highest mountain, a challenge embraced by many artists before and after him. The accuracy in these pieces was paramount, not only for aesthetic reasons but also for the burgeoning tourist market eager for faithful souvenirs of their Alpine adventures.

A Scientific Eye: Linck's Unintentional Contribution to Glaciology

Beyond their artistic merit, Jean Antoine Linck's paintings and drawings hold considerable scientific importance, particularly for the study of historical glaciology. In an era before widespread photography, detailed and accurately dated artistic representations of glaciers provide crucial visual evidence of their past extent and fluctuations. Linck's meticulous renderings of glacial snouts, moraines, and overall ice volume have allowed modern scientists to reconstruct the positions of glaciers like the Mer de Glace during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

This period coincided with the end of the Little Ice Age, a multi-century span of generally cooler temperatures and glacial advance. Linck's works capture these glaciers often at or near their maximum Holocene extents, before the more sustained and dramatic retreat observed from the mid-19th century onwards. By comparing his depictions with later paintings, photographs, and direct measurements, researchers can track glacial changes with greater precision. His work, therefore, serves as an important baseline, offering data points that complement other forms of historical evidence.

This scientific utility was likely not Linck's primary intention; he was, first and foremost, an artist captivated by the visual splendor of the Alps. Yet, his commitment to accurate observation, a hallmark of the Enlightenment spirit, inadvertently created a valuable scientific archive. In this, he joins other artists like Samuel Birmann (1793-1847) of Basel, who also produced detailed Alpine views, and even earlier figures like William Pars (1742-1782), an English artist who documented Alpine scenes with a concern for topographical accuracy.

Linck and His Contemporaries: An Artistic Landscape

Jean Antoine Linck operated within a vibrant artistic context, both in Geneva and in the broader European sphere of landscape painting. In Switzerland, he was part of a tradition of Alpine painters that included the aforementioned Caspar Wolf, whose dramatic and often scientifically informed views of the Alps set an important precedent. Samuel Birmann, a younger contemporary, also specialized in Alpine scenes, often in watercolor, and his work, like Linck's, is valued for its topographical accuracy and artistic sensitivity.

Geneva itself was home to other notable landscape artists. Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer (1766-1847), an exact contemporary of Linck, was known for his charming genre scenes and landscapes that often depicted the Genevan countryside and its people, offering a different, more pastoral perspective than Linck's high Alpine focus. François Diday (1802-1877) and his student Alexandre Calame (1810-1864) would later become leading figures of the Swiss Romantic landscape school, carrying the tradition of Alpine painting into the mid-19th century with great international success. While their styles evolved, the groundwork laid by artists like Linck was instrumental. Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1767-1849), another Genevan contemporary, was renowned for his animal paintings but also produced sensitive landscapes.

Beyond Switzerland, the interest in sublime landscapes was a pan-European phenomenon. The works of British artists like J.M.W. Turner, with his dynamic and light-filled Alpine watercolors and oils, and John Constable (1776-1837), with his dedication to the naturalism of the English countryside, reflect parallel developments in landscape art. The German Romantic painters, notably Caspar David Friedrich, explored the spiritual and emotional dimensions of nature, often using mountainous or wild settings. While Linck's style differed, he shared with these artists a profound engagement with the natural world as a primary subject for art. The influence of earlier classical landscape painters like Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) also lingered, particularly in terms of compositional strategies and the ideal of a harmonious, if sometimes awe-inspiring, natural order.

The Studio at Montbrillant and Artistic Circles

Jean Antoine Linck established his studio in the Montbrillant district of Geneva. This location was strategically significant, as Montbrillant served as a gateway for travelers heading towards the Savoy Alps. His studio became a popular stop for tourists, including many British visitors undertaking the Grand Tour, who were eager to acquire visual mementos of their Alpine experiences. These "souvenirs" were often highly detailed watercolors, gouaches, or prints, showcasing Linck's skill and catering to a discerning clientele.

His reputation extended to prominent figures. It is recorded that Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, wife of Napoleon, was among those who admired and possibly acquired his work. The patronage of such high-profile individuals significantly boosted an artist's career and visibility. Sources also mention that by 1809, his patrons included figures associated with the Russian court (sometimes anachronistically cited as Catherine II, who died in 1796, but more likely other Russian aristocrats or later imperial family members acquiring works for collections like the Hermitage) and Cardinal Joseph Fesch, Napoleon's uncle and a renowned art collector.

Linck was also an active participant in Geneva's artistic life. He was a member of the Société des Arts de Genève (Geneva Society of Arts), an important institution founded in 1776 to promote arts, agriculture, and industry. Participation in the Société's exhibitions would have provided Linck with a platform to showcase his work to a local and international audience, engage with fellow artists, and solidify his reputation. His involvement suggests a commitment to the professional art community of his city. The assertion that his studio was a frequent gathering place for other artists and travelers further underscores his role within this community, fostering an environment of exchange and appreciation for Alpine art.

Innovations in Technique and Dissemination

A noteworthy aspect of Linck's practice was his innovative approach to disseminating his Alpine views. He recognized the growing demand for his images and employed printmaking techniques, particularly etching, to create reproducible versions of his compositions. He would produce large-format etchings, which could then be hand-colored with watercolor or gouache, effectively creating unique variations of a printed base. This method allowed for wider distribution of his work than would have been possible with unique paintings alone, making his art accessible to a broader audience while still retaining a degree of hand-finished artistry.

This practice was not unique to Linck—hand-colored prints were a popular medium in the 18th and 19th centuries—but his application of it to the specialized genre of Alpine views was particularly successful. It combined the accuracy of his draughtsmanship, captured in the etched line, with the atmospheric effects and vibrant hues achievable through hand-coloring. This entrepreneurial spirit, coupled with his artistic talent, contributed significantly to his contemporary success.

Anecdotes and Personal Dedication: The Artist as Explorer

Linck's artistic career was characterized by a deep personal commitment to his subject matter. His regular summer excursions into the Chamonix valley and other Alpine regions were not mere leisurely trips but intensive periods of fieldwork. Armed with sketchbooks, he would spend considerable time observing and recording the landscapes, often under challenging conditions. These expeditions required physical stamina and a spirit of adventure, qualities that aligned with the era's growing fascination with Alpinism.

These field sketches, rich in authentic detail and capturing fleeting effects of light and weather, were invaluable resources. Back in his Geneva studio, he would transform these initial impressions into more elaborate and finished compositions. This two-stage process—direct observation in nature followed by studio refinement—was crucial to his ability to create works that were both accurate and aesthetically compelling. His marriage in 1802 to Jeanne-Pernette Bouvier, who came from a notable Genevan family, likely provided him with greater social standing and stability, further supporting his artistic career.

Legacy and Enduring Influence: A Reassessment

Despite his contemporary success and the evident quality of his work, Jean Antoine Linck's posthumous reputation has experienced fluctuations. For a time, he was perhaps overshadowed by later, more overtly Romantic Alpine painters or by artists with stronger international profiles. The fact that many of his works remain undated or their provenances unclear has also presented challenges for comprehensive art historical assessment.

However, in more recent times, there has been a growing recognition of Linck's unique contributions. Art historians and curators increasingly appreciate the finesse of his technique, the sincerity of his vision, and the historical importance of his Alpine depictions. Exhibitions featuring Swiss art or the art of the Romantic period have helped to bring his work to a wider public.

Crucially, his significance to fields beyond art history, particularly glaciology and environmental history, has cemented his legacy. As concerns about climate change and glacial retreat intensify in the 21st century, Linck's paintings from two centuries ago take on new relevance, offering poignant visual testimony to a world that has profoundly changed. They remind us of the long-term dynamics of Earth's systems and the role that art can play in documenting and interpreting environmental transformations.

His influence can be seen in the continuing tradition of Alpine painting in Switzerland and beyond. Artists who followed, whether consciously or unconsciously, built upon the visual language and thematic concerns that Linck and his contemporaries helped to establish. He was a pioneer in demonstrating that the high Alps were not just a backdrop but a worthy and complex subject in their own right, capable of inspiring both scientific inquiry and profound aesthetic emotion.

Conclusion: Chronicler of a Changing Landscape

Jean Antoine Linck (1766-1843) was an artist of remarkable skill and dedication, whose life's work was inextricably linked to the majestic Alpine landscapes of his native Switzerland. Through his meticulous drawings, vibrant watercolors, and innovative prints, he not only captured the sublime beauty of mountains and glaciers but also left an invaluable record of their state at a pivotal moment in environmental history.

His fusion of Enlightenment precision with Romantic sensibility created a body of work that continues to resonate with viewers today. As a key figure in the development of Alpine landscape painting, a respected member of Geneva's artistic community, and an unwitting contributor to scientific understanding, Jean Antoine Linck's legacy is rich and multifaceted. His art invites us to marvel at the grandeur of the natural world and to reflect on its enduring power and its delicate, ever-changing nature.