Samuel Daniell (1775-1811) stands as a significant, albeit short-lived, figure in the annals of British art, particularly renowned for his pioneering depictions of the landscapes, wildlife, and indigenous peoples of Southern Africa and Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) at the turn of the 19th century. His work, characterized by a keen eye for detail and a sympathetic portrayal of his subjects, offers invaluable visual records of regions then largely unfamiliar to European audiences. As a member of the distinguished Daniell family of artists, he inherited a tradition of travel and topographical art, which he applied with remarkable dedication during his brief but impactful career.

The Daniell Artistic Dynasty

Samuel Daniell was born into a family already making its mark on the British art scene. His uncle, Thomas Daniell (1749–1840), and his elder brother, William Daniell (1769–1837), were highly acclaimed artists. Thomas, accompanied by William, had embarked on an extensive tour of India from 1786 to 1794. Their monumental work, "Oriental Scenery," published in several parts between 1795 and 1808, comprised 144 exquisitely detailed aquatint views of Indian architecture, landscapes, and daily life. This publication was a sensation, profoundly shaping European perceptions of India and setting a high standard for topographical and picturesque art.

The success of Thomas and William Daniell undoubtedly influenced Samuel. Their meticulous approach to recording foreign lands, combined with the artistic skill to transform field sketches into compelling published prints, provided a clear model. The family's engagement with the East, particularly India, was part of a broader European fascination with distant lands, fueled by exploration, trade, and colonial expansion. Artists like William Hodges (1744–1797), who had accompanied Captain James Cook on his second voyage and later worked in India under Warren Hastings, and Johan Zoffany (1733–1810), who painted vibrant scenes of colonial life in Lucknow and Calcutta, were contemporaries who also contributed to this visual documentation of empire and discovery. The Daniells, however, distinguished themselves through the sheer scale and comprehensiveness of their Indian project.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Samuel Daniell was born in Chertsey, Surrey, in 1775. Growing up in such an artistic environment, it is almost certain that he received his initial training from his uncle Thomas and brother William. He would have been exposed to their drawings and prints from India, learning the techniques of sketching in the field, watercolor painting, and the processes involved in creating aquatints for publication. The Royal Academy of Arts in London was the premier institution for artists, and like his relatives, Samuel likely aspired to exhibit there, honing his skills in draughtsmanship and composition.

While less is documented about Samuel's early career in England compared to his overseas adventures, his later proficiency suggests a solid grounding in the artistic conventions of the time. The emphasis was on accurate representation, often filtered through the aesthetic of the "picturesque," which valued variety, irregularity, and interesting textures in landscapes and architectural subjects. This foundation would prove crucial when he ventured into the unfamiliar terrains of Africa and Ceylon.

Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope

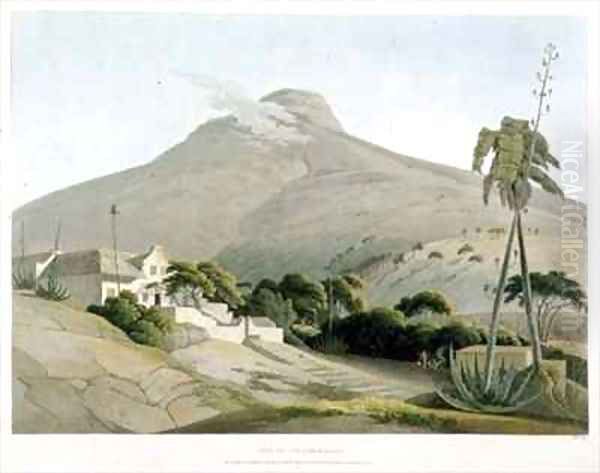

In late 1799 or early 1800, Samuel Daniell embarked on a journey that would define his artistic legacy: he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in Southern Africa. At this time, the Cape was under British control, having been taken from the Dutch. It was a strategic port and a gateway to a vast and largely unexplored interior. For an artist with an adventurous spirit and a desire to document new worlds, Southern Africa offered immense possibilities.

Upon his arrival, Daniell began to sketch the local scenery, the diverse flora and fauna, and the various groups of people inhabiting the region, including the Dutch settlers, the indigenous Khoikhoi (then often referred to as Hottentots), and the San (or Bushmen). His presence at the Cape coincided with a period of increased British administrative and exploratory interest in the colony and its hinterlands.

The Truter-Somerville Expedition to Bechuanaland

A pivotal moment in Samuel Daniell's African sojourn came in 1801 when he was appointed official secretary and draughtsman to an important expedition. This expedition, led by Petrus Johannes Truter, a member of the Cape Court of Justice, and Dr. William Somerville, a physician and later Inspector-General of Hospitals at the Cape, was dispatched by the British authorities. Its primary objective was to journey northwards from Cape Town into the interior, to the territory of the Tswana people (then referred to as the "Bechuana" or "Bootchuana"), in what is now part of Botswana and South Africa. The mission aimed to establish friendly relations, explore trade possibilities, and gather information about these little-known peoples and their lands.

The expedition, which lasted from October 1801 to April 1802, was arduous. It traversed challenging terrain, from the settled regions around Cape Town, through the arid Karoo, and into the lands beyond the Orange River. For Samuel Daniell, this was an unparalleled opportunity. As the official artist, his role was to create a visual record of everything of interest: the landscapes, the geological formations, the unique animals and plants, and, crucially, the Tswana people, their villages, customs, and appearance.

During this journey, Daniell is credited with being one of the first Europeans to visit and depict the "Kuruman Eye," a significant natural spring that forms the source of the Kuruman River. This oasis in a generally dry region was, and remains, a vital water source. His sketches from this expedition formed the bedrock of his first major publication. He meticulously documented the Tswana people, their distinctive karosses (cloaks made of animal skins), their weaponry, and their settlements, such as Lattakoo (Dithakong).

Artistic Output from Africa

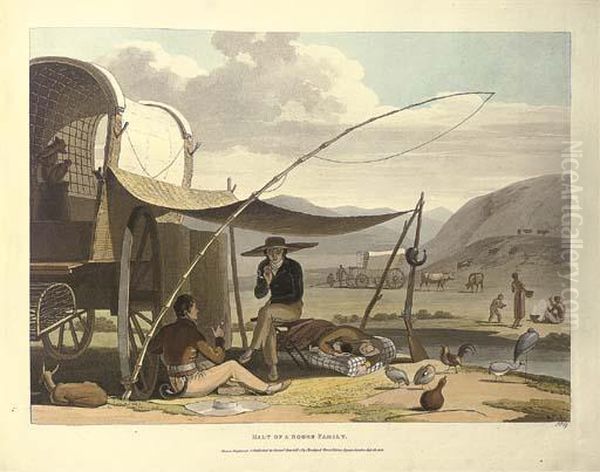

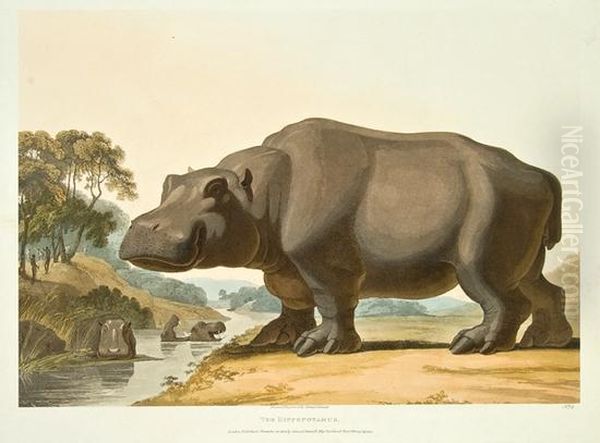

Samuel Daniell's African sketches and watercolors are remarkable for their time. He worked with a directness and an observational acuity that sought to capture the reality of what he saw. While the picturesque aesthetic still informed some of his compositions, his primary drive appears to have been documentary. He depicted a wide array of African wildlife, often with considerable accuracy, including species that were new or exotic to European eyes. His drawings of rhinoceros, gnu (wildebeest), various antelope species like the springbok and kudu, quagga (an extinct subspecies of plains zebra), and warthogs are particularly noteworthy.

His portrayals of the indigenous peoples are also of immense historical and ethnographical importance. He drew portraits of Khoikhoi, San, and Tswana individuals, often highlighting their attire, adornments, and characteristic features. Scenes of daily life, hunting practices, and encampments provide glimpses into cultures that were undergoing profound changes due to colonial expansion. Unlike some contemporary depictions that tended towards caricature or romanticization, Daniell's work often conveys a sense of dignity and individuality in his human subjects. He was among the first professional European artists to provide such a comprehensive visual account of the peoples of the Southern African interior.

"African Scenery and Animals"

After his return to England in 1803, Samuel Daniell set about preparing his African drawings for publication. The result was "African Scenery and Animals," a magnificent folio work published in two parts in 1804 and 1805. It consisted of thirty large, hand-colored aquatint plates, engraved by Samuel himself, with the assistance of his brother William Daniell, who was an acknowledged master of the aquatint process. Aquatint, with its ability to create tonal variations, was perfectly suited to reproducing the subtle washes of watercolor and the atmospheric effects of Daniell's original drawings.

This publication was a landmark. It provided the British public and the scientific community with some of the most accurate and visually striking images of Southern Africa yet seen. The plates covered a range of subjects: panoramic landscapes, detailed studies of animals in their natural habitats (such as "The Gnoo," "A Koodoo," "Plaat Bergs Rivier"), and depictions of indigenous life (like "A Hottentot Village," "Booshuanas," "Bosjesmans frying Locusts"). "African Scenery and Animals" is now considered one of the rarest and most valuable illustrated books on South Africa, a testament to its artistic quality and historical significance. Its influence can be seen in the work of later artists who traveled in Southern Africa, such as Thomas Baines (1820–1875) and Frederick Timpson I'Ons (1802–1887), though their styles and the contexts of their work differed.

Journey to Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

His African work having established his reputation, Samuel Daniell did not remain in England for long. In 1805, he secured an appointment in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which had also recently come under full British control. He traveled to the island, arriving probably in early 1806, to take up a post, possibly as a Ranger of the Woods and Forests or a similar civilian position within the colonial administration. This role would have given him ample opportunity to travel throughout the island.

Ceylon, with its lush tropical environment, ancient ruins, rich biodiversity, and distinct cultures, offered a new canvas for Daniell's talents. He immersed himself in documenting this new environment with the same diligence he had shown in Africa. He sketched the island's dramatic landscapes, from coastal plains to mountainous interiors, its abundant wildlife, particularly elephants, and its diverse population, including the Sinhalese, Tamil, and Vedda communities. During his time in Ceylon, he is known to have collaborated with Maria Graham (later Lady Callcott), a writer and botanist, further highlighting his scientific interests. He also documented specific cultural events, such as elephant kraals (enclosures for capturing wild elephants) in areas like Negombo.

Artistic Depictions of Ceylon

Daniell's Ceylonese artwork continued his commitment to detailed observation. He captured the unique character of the island's flora, such as the towering Talipot palms, and its fauna, with a particular focus on elephants, which played a significant role in both the ecology and culture of Ceylon. His depictions of elephant hunts, tame elephants at work, and wild herds are among his most compelling Ceylonese images.

He also turned his attention to the people of Ceylon, drawing portraits and scenes of village life, religious ceremonies, and traditional occupations. His images of Kandyan chieftains, Buddhist monks, and ordinary villagers provide valuable insights into Ceylonese society at the beginning of the 19th century. He was interested in the architectural heritage of the island as well, sketching ancient temples and dagobas. The artistic challenges were different from those in Africa; the dense tropical vegetation and the quality of light required different approaches to composition and color.

"A Picturesque Illustration of the Scenery, Animals, and Native Inhabitants of Ceylon"

Based on his Ceylonese sketches, Samuel Daniell produced another significant illustrated book, "A Picturesque Illustration of the Scenery, Animals, and Native Inhabitants of Ceylon." This work, consisting of twelve hand-colored aquatint plates, was published in London in 1808. Again, his brother William Daniell likely assisted with the engraving process. The plates included striking images such as "The Elephant Snare at Kotawy," "A Maha Modliar and his Wife," "The Talipot Tree," and "A Singaleze Man & Woman."

This publication, like its African predecessor, brought vivid and accurate representations of a distant part of the British Empire to a European audience. It complemented the growing body of visual material on Asia, which included the extensive works on India by his own family, as well as by artists like George Chinnery (1774–1852), who, though slightly younger, would become famous for his depictions of India and later, China.

A posthumous collection of his African sketches, titled "Sketches Representing the Native Tribes, Animals, and Scenery of Southern Africa," was published by his brother William in 1820. This further disseminated Samuel's important early work from the Cape.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Mediums

Samuel Daniell's artistic style was rooted in the British topographical tradition, which emphasized accuracy and clarity. His primary medium for field work was watercolor, often combined with pencil or ink for outlines. These field sketches were then worked up into more finished watercolors or served as the basis for the aquatint prints. His compositions, while often adhering to picturesque conventions (such as framing devices using trees, or leading the eye into the distance), were generally less romanticized and more documentary than those of some of his contemporaries.

The aquatint process, which he and his brother mastered, was crucial for the dissemination of his work. This intaglio printmaking technique allowed for the creation of broad areas of tone, mimicking the effect of watercolor washes, and was ideal for reproducing landscapes and natural history subjects. The hand-coloring of the prints added to their vibrancy and appeal.

Compared to an artist like William Hodges, whose Indian and Pacific landscapes often had a more dramatic, almost sublime quality, Samuel Daniell's work tended towards a more straightforward, though still aesthetically pleasing, representation. His focus was often on the specific details of an animal's anatomy, a plant's structure, or the attire of an indigenous person. This aligns his work with the burgeoning scientific interest in natural history and ethnography that characterized the period. One might also consider the work of artists on Captain Cook's voyages, such as Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745–1771) on the first voyage or John Webber (1751–1793) on the third, who also faced the challenge of documenting entirely new worlds, their peoples, flora, and fauna, often with a similar blend of artistic convention and scientific observation.

The Broader Context of Travel and Colonial Art

Samuel Daniell's career unfolded during a period of intense global exploration and the expansion of European colonial empires, particularly the British Empire. Artists were often integral to this process, serving various functions. They accompanied official expeditions, documented newly acquired territories, provided visual intelligence, and satisfied the curiosity of the public back home for images of exotic lands and peoples.

Their work contributed to scientific knowledge in fields like botany, zoology, and ethnography. For instance, the detailed botanical illustrations of artists like Franz Bauer (1758–1840) and Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826), who worked at Kew Gardens and traveled on expeditions like Matthew Flinders' circumnavigation of Australia (Ferdinand was on this voyage, as was William Westall (1781–1850) as landscape artist), were vital for scientific classification. While Daniell was not primarily a botanical or zoological illustrator in the purely scientific sense, his accurate depictions of animals and plants in their environments were valuable.

The "picturesque" aesthetic, popularized by writers like William Gilpin, heavily influenced how artists viewed and represented landscapes, both at home and abroad. This aesthetic sought beauty in irregularity, variety, and texture, and often involved a degree of idealization or arrangement of natural features to create a pleasing composition. Daniell's work shows an awareness of these conventions, but his commitment to observation often takes precedence.

It is also important to acknowledge the colonial context in which this art was produced. The artists, including Daniell, were operating within a framework of European power and often depicted indigenous peoples from a European perspective. While Daniell's portrayals are generally considered sympathetic and respectful for his time, the very act of documenting and categorizing was part of the broader colonial enterprise. His patrons and audience were primarily European, and his work helped to shape their understanding – and often, their justifications for colonial rule – of these distant lands. Other artists working in colonial contexts, such as Arthur William Devis (1762–1822) in India, or later, John James Audubon (1785–1851) in America (though focused on ornithology), also navigated this intersection of art, science, and empire.

Untimely Death and Posthumous Recognition

Tragically, Samuel Daniell's promising career was cut short. While still in Ceylon, he contracted a tropical fever, likely malaria, and died in December 1811, at the young age of 36. He was buried in the Pettah cemetery in Colombo. His death was a significant loss to the world of art and exploration.

Despite his early demise, his work continued to be recognized. As mentioned, his brother William ensured the posthumous publication of "Sketches Representing the Native Tribes, Animals, and Scenery of Southern Africa" in 1820, making more of his African drawings accessible. His original watercolors and prints are now held in major collections worldwide and are highly prized by collectors of Africana and Ceylonese art.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Samuel Daniell's legacy is multifaceted. He was a pioneer in the artistic representation of Southern Africa and Ceylon, providing some of the earliest accurate and comprehensive visual records of these regions by a professional British artist. His work is an invaluable resource for historians, ethnographers, zoologists, and botanists studying these areas at the beginning of the 19th century.

His depictions of indigenous peoples, while viewed through the lens of his time, offer important, and often unique, visual information about their cultures, attire, and ways of life before they were more profoundly impacted by colonization. Similarly, his animal and landscape drawings document environments and wildlife populations that have since undergone significant changes.

Within the Daniell family, Samuel's contribution, though briefer, complements the extensive work of Thomas and William in India. Together, they created an extraordinary visual archive of the British presence and interest in the East and Africa. His dedication to firsthand observation and his skill in translating those observations into compelling images set a high standard for travel artists.

Conclusion

Samuel Daniell was an artist of considerable talent and adventurous spirit. In a career spanning little more than a decade of active overseas work, he produced a body of art that remains remarkable for its scope, detail, and historical importance. His depictions of the landscapes, fauna, and peoples of Southern Africa and Ceylon provided Europe with a fresh and often revelatory glimpse into these distant worlds. While his life was tragically short, his artistic achievements endure, securing his place as a key figure in the history of British colonial art and the visual documentation of global exploration. His works continue to be studied and admired, not only for their aesthetic qualities but also as precious windows into the past.